Predistributive Measures Are Essential to Reducing Inequality

The welfare state is essential for keeping the nonworking population out of poverty. But we shouldn’t discount the role of predistributive measures like strong unions and minimum wage laws in reducing inequality.

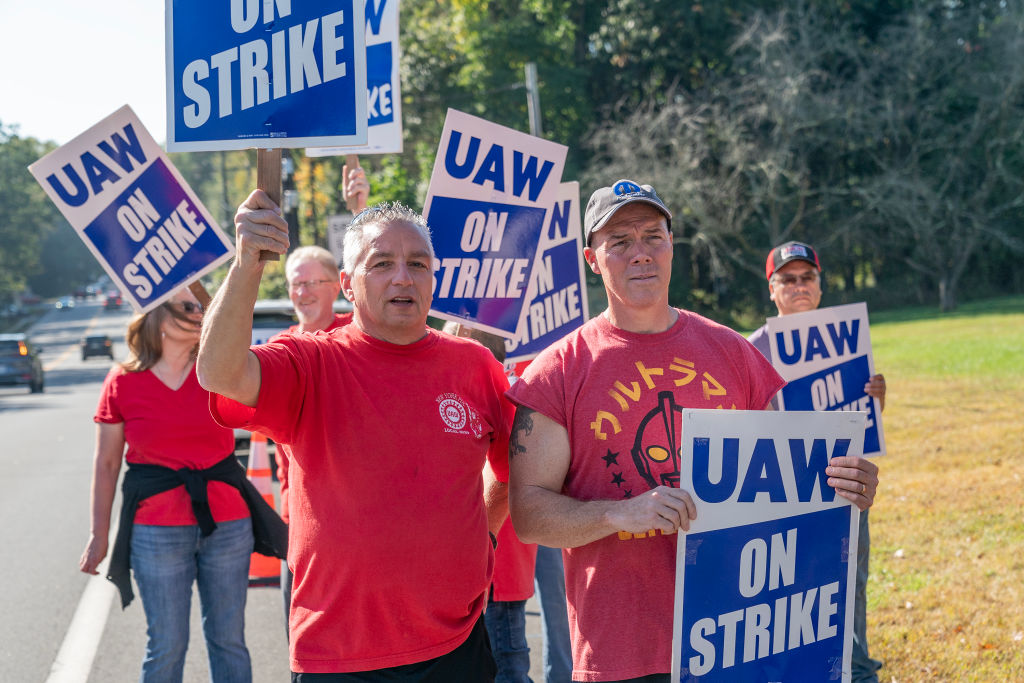

Multiple studies have come to the conclusion that predistributive policies, like collective bargaining regimes, play a central role in reducing inequality. (Lev Radin / Pacific Press / LightRocket via Getty Images)

In response to my article on inequality reduction, Matt Bruenig claims that I am “simply the latest victim” of “the most deceptive paper ever written” on the subject. It is an admittedly odd task to address a critique of one’s argument that solely takes aim at a study used for its hook. For what it’s worth, there are multiple other studies that come to similar conclusions, including one published last month showing that the equality of the Nordic countries’ economies is explained to a greater extent by their two-tier wage bargaining systems than by the breadth and generosity of their taxes and transfers.

Nonetheless, it is worthwhile to challenge Bruenig’s characterizations of the paper in question by Thomas Blanchet, Lucas Chancel, and Amory Gethin. For one, I do not consider it to be “deceptive,” as Bruenig insists. But more importantly, doing so allows me to restate more clearly the central point of my article that Bruenig seems to have missed, which is that welfare provision (redistribution) and market-income compression (predistribution) serve different purposes — a view that is in fact complementary to his.

Like Bruenig, I would caution against discounting the importance and efficacy of redistribution in serving the neediest in society. However, in line with other developed countries, the United States does redistribute a significant portion of its market income. Despite this, it is an extreme outlier in most customary indicators of economic inequality. Most of that enduring inequality is explained by its comparatively meager efforts at predistribution.

Redistribution of What?

First, let’s look at how Bruenig frames his critique. He writes:

When trying to figure out what is most responsible for low inequality in developed countries, the welfare state always beats market-income compression for one simple reason: half of the population does not work. The nonworking half of the population drives up market inequality because they add a ton of zeroes to the bottom of the market income distribution. Providing welfare benefits to this nonworking half replaces those zeroes with positive numbers in direct proportion to how generous the welfare state is. The effect of moving these zeroes to nonzeroes completely overwhelms any other inequality-reduction mechanism.

Bruenig is surely aware that whether the mechanism he adduces to the welfare state regarding inequality reduction “beats” others is an empirical matter. It depends not just upon (1) the size of the population that does not work but also (2) the proportion of nonworkers with no income other than government transfers, (3) the generosity of these transfers, (4) the progressivity of the taxes used to fund the transfers, and finally (5) the magnitudes of the educational, skill, and firm-specific premiums, in addition to capital and managerial incomes, that market-income compression — that is, predistributionary policy — could realistically erode. We cannot deduce a priori (“always,” “completely overwhelms”) where the chips will fall, which is probably why Bruenig loads his description by stating that “half the population does not work” when, even in developed countries, rates of labor force participation vary by tens of percentage points.

Bruenig has two principal lines of attack on the Blanchet et al. article. The first is that the authors use a definition of pretax income that is net of the payroll taxes that fund certain social contributions, including public pensions as well as unemployment and disability insurance. He repeatedly casts aspersions on their use of this definition, as if it were an accounting “trick” peculiar to them, when in fact this is the way most states around the world measure pretax income. In the United States as in Europe, income taxes are assessed net of payroll taxes, largely to avoid placing individuals in a higher tax bracket than is justified. Blanchet et al. are for the most part following this uncontroversial convention here, which allows them to accurately measure the redistribution that governments conduct through income taxes. (I write “for the most part” because they do not net out the minuscule component of payroll taxes — around 6 percent on average — that goes toward noninsurance forms of redistribution.)

What Bruenig is criticizing, then, is not the definition of pretax income but the fact that Blanchet et al. use pretax income rather than factor income — the market income before payroll taxes are deducted — as the benchmark by which to make the comparison with posttax income, including noncash transfers. One can certainly make the case that using the pretax benchmark underestimates the role of redistribution, although, as I elaborate below, that case is not as airtight as Bruenig believes.

However, what one cannot claim is that Blanchet et al. ignore this distinction. Further along in their paper, as well as in an online appendix, they repeat their exercise juxtaposing the posttax top 10 and bottom 50 percent income shares across the United States and Europe utilizing both benchmarks. They find that while redistribution plays a somewhat larger role when using the factor income benchmark, their headline result is unchanged. Blanchet et al. comment that this is due to their inclusion of new data sources, which corrects for the underreporting of top incomes and the exclusion of corporate and indirect taxes in traditional surveys.

Blanchet et al. offer a clear rationale for using the pretax income benchmark throughout most of their paper, a methodological choice that Bruenig dislikes but that can hardly be described as “deceptive.” It also doubles as a response to Bruenig’s second line of attack, which is that the authors do not include the incomes of children in their measurement of inequality. Because the vast majority of the money shuffled around through payroll taxes (nearly 90 percent on average) goes to pensions, Blanchet et al. argue that using factor income as the benchmark allows for demographic factors to contaminate the evaluation of the effectiveness of inequality-reducing policies. If two countries have equally generous public pension systems but one has twice the number of retirees per capita as the other, by the factor income benchmark it is wildly more redistributive. But is that what we intend to capture when we are comparing inequality regimes? (This does not touch the added problem that private pensions pose for the factor income benchmark, since they would be inappropriately included as part of “redistribution.”)

Predistribution and Redistribution

This brings me back to the thrust of my original piece, which is that we are largely equivocating when we pit redistribution and predistribution against one another. Moreover, and as I wrote, this is precisely for the reasons Bruenig has laid out in his previous work. There is an obvious motivation for why we tend to discount the “zeroes” of retirees and especially children in academic and popular discourse about economic inequality: we do not expect them to be involved in income-generating activity in the first place. (In another Jacobin article on this topic, Martin Bernstein nets out public and private pensions but keeps unemployment and disability insurance out of his pretax income benchmark. I think this comes closer to the mark.)

The language around the penury of retirees and children that programs like Social Security rectifies usually tends to shift to that of poverty, not inequality. Not coincidentally, the term “inequality” barely makes an appearance in Bruenig’s excellent piece on the nature of contemporary poverty.

This is not a matter of semantics. When Bruenig writes that poverty is principally a matter of the problem of nonworkers under capitalism, I agree with him wholeheartedly. But by his own accounting, over three-fourths of nonworkers in the United States are children, students, and the elderly. (The number rises to over 90 percent when including the non-elderly retired and the disabled.) My own modest claim is that if, as he contends, redistribution mostly acts to remedy the problem of the “zeroes,” it should not come as a surprise that it does little to reduce the asset inequality that governs the lives of working people. The welfare state cannot be expected to solve problems it was not designed to solve.

It may even be the case that adjusting inequalities in market incomes downward contributes more to inequality reduction, defined as broadly as possible, than does bolstering welfare provision for those who cannot participate in the market. Considering that the working-age population still constitutes the majority in developed economies (for now), that by definition virtually all economic output comes from their activity, and that social coinsurance can be — and not infrequently is — funded by taxation schemes that are not especially progressive, this possibility is not as implausible as Bruenig makes it out to be.

But that is ultimately independent of the motivation behind my original article, which is that the conceptual distinction between welfare provision and market-income compression matters quite a lot for our politics. To repeat, a country can redistribute a healthy amount of its output to its children and elderly and still be riven by grotesque inequalities in income, wealth, and hence political power. I would argue that this is what distinguishes the United States (and to a lesser extent, the United Kingdom) from the rest of the developed world. Socialists in America ought to take notice.

It is unfortunate that Bruenig’s animosity toward the Blanchet et al. paper did not allow him to see the considerable amount of overlap in our views. It would be far more fruitful to discuss how socialists can and have bridged the welfare-state politics of redistribution with the market-shaping politics of predistribution. The classical social democrats in the Nordic countries certainly did, since they set up their centralized bargaining systems well before they implemented the universal welfare programs for which they are so famous.

I will end by restating my original thesis in less technical language. If you want to address the problem of poverty, tax incomes to grow the welfare state. And if you want to address the problem of inequality, that is, the gulf in power and resources on the market and in the workplace that is constitutive of the class struggle, change the rules of the game.