The Red Scare Is American Past and Present

If we want to understand how we arrived in this authoritarian moment in 2025, we need to understand one of the central pathways that brought us here: McCarthyism.

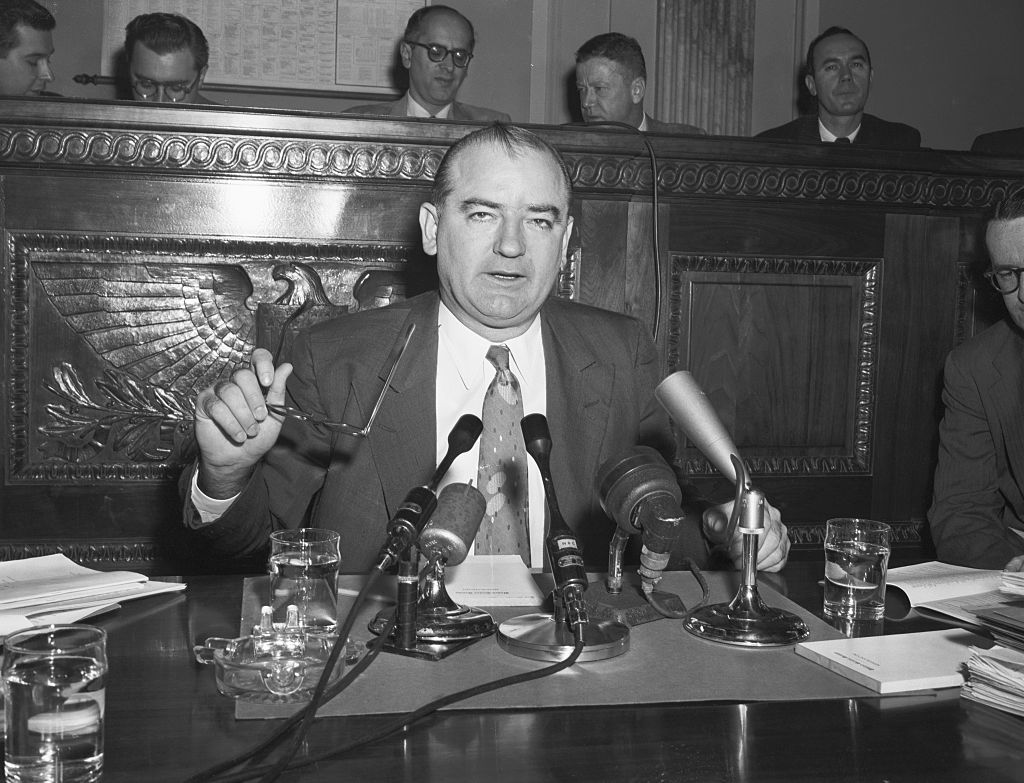

As we enter something like another red scare, one that seemed to many liberals and even leftists impossible to conceive of months before its machinery started, we should study previous red scares in American history like McCarthyism. (Getty Images)

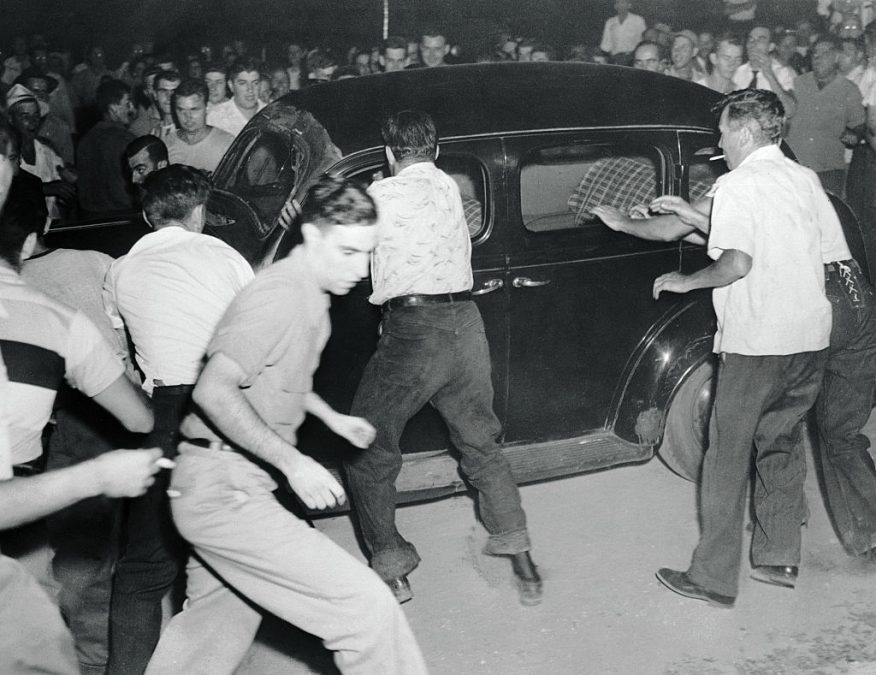

In his firsthand account of the 1949 Peekskill Riot, the two-day frenzy of state-sanctioned mob violence against a left-wing music festival headlined by Paul Robeson, writer Howard Fast mostly describes his disbelief. He was invited to help first with the planning and then with the defense of the concert, as mobs of vigilantes with clubs, knives, and guns shut down the performances, violently assaulted many of the attendees, and forced Robeson into hiding. Fast, in the face of mobs shouting racist and antisemitic slogans, believed they could bring Robeson back a week later, with a cordon of United Electrical and Longshoremen union members ringing the concert. The exit from the fairgrounds became a living hell: a gauntlet of thrown rocks, smashed windows, overturned cars, and concertgoers beaten within inches of their lives, including the first Black military aviator in World War I, Eugene Bullard.

After driving through a hail of rocks and slurs, Fast recorded in his book Peekskill, USA his stunned disbelief at seeing the glistening, wet pavement around the burning metal carcasses of smashed-up cars. At first thinking the slick rivulets were gasoline or oil, he realized the streams were blood from the fleeing concertgoers. He recalls a sense of disassociated unreality: this could not, he thought, be happening. Remembering the conversations with others after the violence over the weekend — no strangers to the Left or struggle — “their talk was uneasy and troubled. They were trying to understand what had happened, what had changed . . . a pervading difference had come to the place; they had to know what that difference was.”

I have thought of Fast’s account as I assume many, like myself, are in an equal state of stunned disbelief at the rapidly unfolding repression of the second Donald Trump administration. Every week brings crises that would be remarkable if they occurred only once in a decade: the calling of federal troops into major US cities, live assassination of migrants in international waters, labeling of “anti-fascist” organizations as domestic terrorists, the abduction and deportation of students for acts of constitutionally protected speech, the creation of politically targeted “antisemitism” lists of pro-Palestine faculty, ICE agents swarming major cities and rounding up migrants in the street, the defunding of major private research universities, the gutting of federal agencies, the embrace of dangerous quack medical science.

Like Fast reading reports that the local American Legion were planning to assassinate Paul Robeson, or even seeing literal blood in the streets, the disorientation of the violence is not only the somatic shock of that violence: it is that, as Fast relates, a short time before, such things did not seem possible.

What Fast was witnessing was the early unfolding of the Second Red Scare, the decade-long suppression, arrest, deportation, terrorization, and occasional public execution of Communists and other leftists in the United States. As we enter something like another red scare, one that seemed to many liberals and even leftists impossible to conceive of months before its machinery started, it’s helpful to remember what we are analogizing.

Historian Ellen Schrecker refers to the era sometimes known as “McCarthyism” (a label she and others dispute) as “the most widespread and longest-lasting wave of political repression in American history.” The Second Red Scare started well before and lasted long after the demise of the demagogue from Wisconsin, Senator Joseph McCarthy; what is at stake in his memorialization is the scope and scale of the repression.

For many, the Second Red Scare was a minor incident, a bump on the road toward achieving and fulfilling a twentieth-century liberal consensus marked by the triumphs of civil rights and the feminist and LGBT movements a decade later. Indeed, many academic histories of “postwar liberalism” barely mention the Second Red Scare. In mass culture, even when it is the focus of a film like Trumbo or Goodnight and Good Luck, one gets the sense that it mainly involved the persecution of a few Communists in the film industry — tragic perhaps, but with little lasting impact on the wider American culture and American politics. The recent TV series For All Mankind presented the Second Red Scare as primarily a civil rights issue for queer federal workers, which it certainly was — and yet, not a wave of political repression of which anti-queer violence was one form of violence among many.

By official counting, two people were executed by the state, several hundred academics were fired, several thousand went to prison or were deported, and several tens of thousands lost their jobs as state or federal workers. While the Red Scare “was not Nazi Germany,” to quote Schrecker, that one even needs to declaim it as such is telling. As Herbert Marcuse wrote in the last years of his life, the Red Scare inaugurated “a new stage of development” in the “Western world,” one that echoes the “horrors of the Nazi regime,” a state of “permanent counter-revolution” against “every thing” that is “called ‘communist.'”

Left writers at the time frequently made the analogy between the Second Red Scare and fascism. A popular pamphlet released by the left-wing Pacific Publishing claimed that Joe McCarthy was “spearhead of fascism” and “on the path of Hitler.” Jewish Life was even less tentative: “McCarthyism is fascism.” Mike Gold called it “Nazi America.” That its death toll was nowhere near classically fascist regimes does not mean the Second Red Scare’s targets and aims were not the same: to crush the Left and, especially, crush any possible alternative to capitalism or American global hegemony. If we want to understand how we arrived in this authoritarian moment in 2025, we need to understand one of the central pathways that brought us here, the Second Red Scare.

An American Night

If the Red Scare had only fired, imprisoned, and publicly executed members of the Communist Party, it would have been enough to dramatically alter the terrain of politics in the United States. As much as the Communist Party is remembered for some unsavory positions, from the support of the Nazi-Soviet Pact to turning around just over a year later to support the US government’s “no strike pledge” during World War II to defense of Joseph Stalin, the CPUSA was, in the words of historian Michael Denning, the “most important left-wing political organization of the Popular Front era.”

Without many of the party’s key campaigns and coalitions, it is very possible the 1930s in the United States would have looked less like the New Deal and more like Peron’s Argentina or Franco’s Spain: there were not only real far-right movements in the United States, many of the elite business interests were hostile to even the program of social reforms proposed by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. From organizing marches of the unemployed in the early 1930s, the defense of nine Black youths falsely accused of rape in Scottsboro, Alabama, to forming the backbone of early Congress of Industrial Organizations, as one labor organizer put it, “social security, unemployment insurance, early de-segregation orders were the direct result of Communist Party’s organizing.”

Yet the real effect of the Second Red Scare went far beyond the suppression of active Party members and other Marxists. Paul Robeson, C.L.R. James, W.E.B. Du Bois, Dorothy Healey, Mike Gold, John Garfield, William Patterson, Richard Wright, Arthur Miller, Leonard Bernstein, Herbert Aptheker, and Claudia Jones were only some of the artists and intellectuals who were deported, lost their jobs, fled the country, had their passports revoked, and/or were jailed under the Smith Act.

And numerous popular, populist civil rights and labor organizations that were either led by Communists or loosely affiliated with the CPUSA as “front” organizations were banned or hemorrhaged members, including a broad base of noncommunists, from the Council on African Affairs, the Civil Rights Congress, The Committee for the Protection of the Foreign Born, the anti-Zionist Jewish People’s Fraternal Order, the Yiddish language newspaper Morgen Freiheit, anti-fascist organizations such as the American League against War and Fascism and the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League (later American Peace Mobilization), even early environmentalist organizations such as Friends of the Earth.

Such broad-based organizations made connections among anti-fascist, anti-racist and ecological thinking in a socialist framework. Fighting capitalism was to fight racism, and vice versa. The liberal, national, and often pro-business framework of the post–Second Red Scare early civil rights movement looked very different from the politics of the Civil Rights Congress or the National Negro Congress.

That it took until the late 1960s for organizations such as Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) or the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) to connect racism, imperialism, and capitalism together suggests how much the later movements were impacted by the absence of a strong, already-existing Marxist left. It’s an open question how much of the later fracturing of the New Left might have owed to the length of time it took to develop such keen intersectional thinking. Movements of the post–New Left fractured over questions of race as against class; Marxists of the Popular Front era often saw these as co-constitutive.

Anatomy of a Curtain Call

While the Second Red Scare touched nearly every facet of American life, from small-town Parent Teacher Association meetings, to the state department, to neighborhood foreign language clubs, to arson and vigilante campaigns waged against union halls and socialist summer camps, one story perhaps like no other encapsulates the level of coordination among state, civic, and cultural institutions to censor and destroy the Left and eradicate wholesale all left cultural or political expression: the suppression of a single film, Salt of the Earth.

Salt was created by blacklisted filmmakers Herbert Biberman, Michael Wilson, and Paul Jarrico, all of whom lost their jobs (and, in Biberman’s case, spent a year in jail under the Smith Act). They formed their own film company in response to their newfound unemployment in the hopes they might be able to secure private funding to make progressive films. While they considered several biographical plots — John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry, a single mother who lost her children after being investigated by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) — when Jarrico witnessed a miner’s strike in New Mexico by a left-led, mostly Chicano union fighting against a racist pay gap, he knew he found his “story.”

The union, Mine-Mill Local 890, faced a Taft-Hartley injunction that forbade picketing by striking miners — yet did not include the miners’ wives. Taft-Hartley was part of a panoply of lawfare, key to the Second Red Scare, directed at curtailing strikes, firing Communist union officials, and ending the ability for unions to act in solidarity with one another through a ban on “secondary boycotts.” While Mine-Mill did not defeat Taft-Hartley, in a move prescient of the later feminist movement, a picket line of miners’ wives took over the strike, repeatedly chasing off waves of strike breakers. The union crossed the gender line and proved that unions are not only organizations that represent their own workers, but entire communities.

When Biberman, Jarrico, and Wilson wrote the script, they also submitted it to the union for democratic review by members and, in a remarkable worker-artist collaboration, rewrote several scenes the miners deemed stereotypical or offensive to the Catholic sensibilities of the community. (Also with much alarm by Biberman and Wilson, union members removed most of the references to the Korean War or US imperialism.) Yet what emerged was a pared-down, tightly woven script that blended a workers’ struggle for safety, an anti-racist struggle for equal wages, and a feminist struggle for recognition and equality within the home.

Although it was one of the finest films of the 1950s, Hollywood executives, Hollywood union leadership, and the FBI met during shooting to prevent the film from being finished. They succeeded in closing film processing centers and stopping sound technicians from being able to process their work, a score from being recorded, and the film from being distributed or shown in the United States. They deported the lead actress, Rosaura Revueltas, to Mexico. Vigilantes showed up on the set and shot at crew members; the Mine-Mill labor hall was burnt down, and the Mine-Mill staffer Clint Jencks was severely beaten and forced, through the Taft-Hartley affidavit, to resign from the union on threat of other union leadership facing prison.

Despite heroic efforts to finish the film (including sneaking film into processing centers, concluding the filming in Mexico, and lying to an orchestra about its content), the film was screened only two times in the United States before no other theater would carry it. The film company was bankrupted with legal fees. The union, Mine-Mill, after decades of waging a struggle for equality in Southwest mines, was raided by another union, the Steelworkers, until it too, went bankrupt, effectively ending its drive to equalized pay and treatment between Chicano and Anglo miners.

This story was an exceptional one, given that it was about a major film production. But in many ways, it was entirely common, revealing the dramatic coordination between vigilante and far-right movements, the state, major corporations, and right-leaning labor unions to commit violence, deportation, censorship, and institutional destruction. The suppression of Salt of the Earth is a story of just how far the Second Red Scare extended past the lives of Hollywood directors and even members of the Communist Party, to destroy an independent film company and a racially integrated, left-led union, relying on vigilante violence and the surveillance power of corporations and the state to carry out its dictates. It was a microcosm of the way state, capital, and conservative forces within the labor movement coordinated to suppress the Left.

Red Scare Governance

Historian and theorist Charisse Burden-Stelly frames red scares as a flexible “mode of governance” which fuses both coercive “public authority” as well as “societal self-regulation” as it reaches its zenith. The United States, Burden-Stelly writes, has a history of red scare governance, from the White Terror that ended Reconstruction to the mass hanging and arrests after the Haymarket Riot, to the deportations and mass imprisonment of the First Red Scare, to the “anti-syndicalist” and “red flag” laws of the early twentieth century, to the Second Red Scare and, later, the assassinations under the FBI regime of COINTELPRO.

Red scares are not singular events, writes Burden-Stelly, but a form of counterrevolutionary governance. They are a portable set of tropes, racial scripts, constructions, and legal forms of repression that can be deployed against the Left, yet require state, business, and political consolidation to be enacted. The Second Red Scare was key in part because it fashioned a legal apparatus still with us today, as the ongoing attempted deportation of Mahmoud Khalil attests. And perhaps more importantly, because it was the first time a red scare of its type systematically went after not only organizations, but all of civil society.

Burden-Stelly notes the Second Red Scare was not only a destructive form of coercion; the advent of the Cold War created the civil and cultural infrastructure of modern liberalism. Civil rights liberals, the Democratic Party, and Jewish and African American organizations accepted anti-communism as the condition for reform. “Loyalty oaths” also created affective if imaginary bonds with the nation and the notion of universal citizenship. When Kamala Harris named Trump a “communist” recently, she likely did not believe that MAGA wishes to seize the means of production, but rather she sought to evoke the Cold War liberal coalition of multiethnic anti-communism as the civic religion of a New Deal state.

Yet as much as the Second Red Scare remade the left wing of the New Deal coalition from “multiethnic social democracy” to “multiethnic anti-communist liberalism,” it’s important to point out that the Communists, even the Left, were not the only — maybe not even the primary — big-picture target of anti-communism. As historian Landon Storrs makes clear, the purging of Communists and socialists from the civil service, federal government, universities, and labor unions not only limited the scope of their politics, it undid many of the more far-reaching reforms of the New Deal itself.

Whether it was the Taft-Hartley Act limiting the right to strike and engage in boycotts, the ending of price controls after World War II, or the adoption of homophobic and patriarchal family policy, the purges not only affected the lives of thousands of state and federal workers (overrepresented among whom were Black, Jewish, and queer employees), but severely curtailed the era of social reform reached by the height of the New Deal. The purging of the state department of scholars and diplomats with expertise in China alone accelerated the Cold War and helped lead to the foreign (and domestic) policy catastrophes of the Korean and later Vietnam Wars.

Historian Kim Phillips-Fein argues similarly that the era of the UAW’s landmark “Treaty of Detroit” with General Motors in 1950 and the supposed cessation of hostilities between the two sides that the contract allowed for hides a longer war of big business against labor. This grand compromise was predicated on further capitalist consolidation, a curtailment of union militancy, a narrowing of union demands to wages and benefits, and, above all, surrender of control of day-to-day working conditions on the shop floor to management. In the 1940s, the CIO wrested an important degree of control of work away from the boss: setting limits on the speed of the assembly line, hiring and firing, and, above all, setting limits to worker discipline by management. In many of the Communist-led unions, such worker self-activity also centered on ending racial segregation in plants and among shop foremen. George Lipsitz, in his work on radical labor movements shortly before the Second Red Scare, recounted one CEO lamenting, “any businessman who says they have control over their factory is a damned liar.”

While the “Treaty of Detroit” has been celebrated for creating an industrial “middle class,” “GM…got a bargain,” wrote Fortune magazine in 1950, as it “regained control over … crucial management functions.” Much in the same way the purging of the “peace camp” from the state department paved the way for the invasion of Vietnam a decade later, so too did the defanging of the labor movement set the stage for the deindustrialization and destruction of working class communities from Detroit to South Shore to Toledo.

Some of the effects of the Second Red Scare were incalculably cultural. When Black Panther activist Assata Shakur first encountered socialist anti-colonial movements, she writes in her autobiography that she felt confused, thinking that socialism was a “white man’s concoction.” In hindsight, her “image of a communist came from a cartoon.” She came to realize that her understanding of anti-colonialism was entirely American: that much of the Third World embraced, if not communism, some form of socialist emancipation. Unless anti-colonial movements were socialist in orientation, “white colonialists would simply be replaced by Black neocolonialists,” concluding

We’re taught at such an early age to be against the communists, yet most of us don’t have the faintest idea what communism is. Only a fool lets somebody else tell him who his enemy is . . . It’s got to be one of the most basic principles of living: always decide who your enemies are for yourself, and never let your enemies choose your enemies for you.

The “early age” during which Shakur learned to be “against communists” was in the late 1950s and early 1960s, in the immediate aftermath of McCarthyism’s peak. Even decades later, anti-communism continues to structure the contours of the law, including legal restraints on labor unions passed in the McCarthy era that are still with us and anti-terror deportation statutes and boycott bans (most currently, bans on boycotting Israel). And anti-communism is deployed discursively to police the boundaries of acceptable politics, from derailing single-payer health care as “socialism,” to scholars such as Timothy Snyder referring to the violent, racist rhetoric of Trump right-hand man Stephen Miller as “communist.” If one compares the United States to industrialized nations that never experienced a comparable red scare, such as France and Holland, one can’t help speculate if their high wages and generous social benefits may owe in no small part to the state’s unwillingness or inability to purge the Left from civil society.

Fascism in an Age of Spectacle

This returns us to the question posed by the Trump administration: what is the relationship between this red scare and the previous one? There are two ways to understand this question. Not only did the hollowing out of liberalism — the decimation of left-led unions, the narrowing of civil rights — help to construct conditions under which the neoliberal counterrevolution could undo the last political vestiges of the New Deal and Great Society, the Second Red Scare also created a cultural legitimacy for anti-radicalism. As a recent Politico article claimed, even while real damage was done, the Second Red Scare “petered out” after McCarthy was defeated, and liberalism benefitted as it was no longer tainted with the unpatriotic association with Communism.

There is, in one sense, a historical lineage; there is also a rupture. As Ellen Schrecker recently argued on Democracy Now!, this current red scare under Trump is “worse” than what came before, as it no longer only targets admitted radicals, but destroys the very institutions of liberalism itself: universities, federal agencies, even the idea of the rule of law. For all of its many crimes, HUAC did at least attempt to make the appearance of adhering to formal liberalism. The current red scare is, like everything under the Trump administration, shambolic, haphazard, and chaotic: it often feels like watching a political tornado more than a concerted effort by a unitary state.

While some of these differences owe to the particular and peculiar geniuses of J. Edgar Hoover and Donald Trump — the former ruthless, methodical, exacting, and programmatic; the latter spectacular, chaotic, and gaudy — perhaps the salient difference is that our current red scare emerges at a vastly different historical confluence of events.

Not only is the far right ascendant globally, decades of neoliberalism have hollowed out the state and produced a social fabric far more segregated, unequal, alienated, and precarious than the 1950s and 1960s. Trump’s assault on liberalism itself is in part due to the fact that there is not only no organized radical left to assault, but that public institutions have far less social support and state investment in the reproduction of civil society than they did eighty years ago.

Richard Seymour calls this form of far-right chaos and devastation “disaster nationalism,” noting how the pastiche of conspiracy theory, doomerism, end-times millenarianism, apocalypse fantasy, blood-and-soil revanchism, terminally online hypermasculinity and hyper-racism are key affective elements of a world that has long since abandoned rational capital accumulation, currency controls, and regulation of high Keynesianism and the welfare state. J. Edgar Hoover was a product of the technocratic organization of the Progressive Era; Trump, a product of the dissolution of postmodern late fascism.

The Second Red Scare also required at least the appearance of consent. For liberals such as Arthur Schlesinger, this appearance of consent was constitutive of the “age of consensus” politics, as both liberals and conservatives joined the attack on the Left. Such appearance of consent also structures the historical narrative: McCarthy could be blamed for the rancor and excesses of the era; the system itself had rational, objective, and popular aims. That Communism was a real threat not only to the ruling class but American democracy itself is accepted not only by conservatives but most liberals. Trump’s new red scare is the product of polarization: it is contemptuous of democratic norms and also of mass consensus. Trump’s enemies are as much “antifa” radicals as the Democratic Party itself.

Trump’s war on consensus and consent poses real dangers of authoritarianism not dreamed of in the 1950s. It also, paradoxically, suggests that the Trump’s red scare may be a paper tiger — one that university administrators, Democratic lawmakers, and much of the media are all too happy to run from as if it were real. As we have seen, protest and pushback can still work: Mahmoud Khalil is no longer in ICE detention (even as he waits for his case to be processed in court); Jimmy Kimmel was reinstated; many states are rolling out their own vaccine schedules despite RFK Jr’s assault on public health; and so on. Even the most authoritarian regimes require willing consent for their regimes to function.

Yet in many ways, we are in the same position Fast was in 1949: watching a violent spectacle unfold in front of our eyes, not yet fully registering or able to know how far into the abyss it will take us. The most important lesson from Fast’s narrative is that, under attack, legal and physical, Communists and other radicals resisted. Fast organized pickets to protect concertgoers; Biberman and Jarrico attempted to make a radical film about a union fighting racism; Communists and their allies in large numbers refused to comply with HUAC investigations, plead the Fifth, and would not name names, even when such refusal landed thousands in jail and many tens of thousands without income. Ethel and Julius Rosenberg refused unto death. Their refusal to comply was consistent with radical left analysis that the Second Red Scare was a form of American fascism — and if one learned anything from the catastrophe of the Holocaust, it was to resist fascism from the beginning until the end.

As Albert Einstein editorialized in 1953, “Every intellectual who is called before one of the committees should refuse to testify, i.e., he must be prepared for jail and economic ruin, in short, for the sacrifice of his personal welfare in the interest of the cultural welfare of the country.” While this may have been cold comfort for those who lost their jobs and their unions, without the example of such resistance, it is unlikely the New Left would have arisen from the ashes of the Old in the 1960s.