America’s Split-Screen Economy

The top 10% are responsible for nearly half of the consumer spending that’s keeping the economy afloat. There’s something disturbing about a tiny number of people having so much money that it effectively masks how poor everyone else is.

Despite the triumphant White House rhetoric, our country’s economy is failing by the metric that matters most, which is whether people who live here are able to meet their basic needs without backbreaking effort. (STR / NurPhoto via Getty Images)

“Americans are spending like never before,” boasted the Donald Trump White House in a press release on Wednesday. “Retail sales are booming — up 5% over last year, far outpacing inflation — as Americans spend in record amounts.”

What the press release neglected to mention, however, is that the top 10 percent of American earners were responsible for almost half of consumer spending in the second quarter.

Their record-high 49.2 percent spending share is keeping the economy looking healthy by some metrics. But stepping back, it’s hard to see good health in an economy where job hiring is slowing down, debt delinquencies are on the rise, and luxury spending by a small cohort is so lavish that it artificially obscures the belt-tightening of a vastly larger cohort.

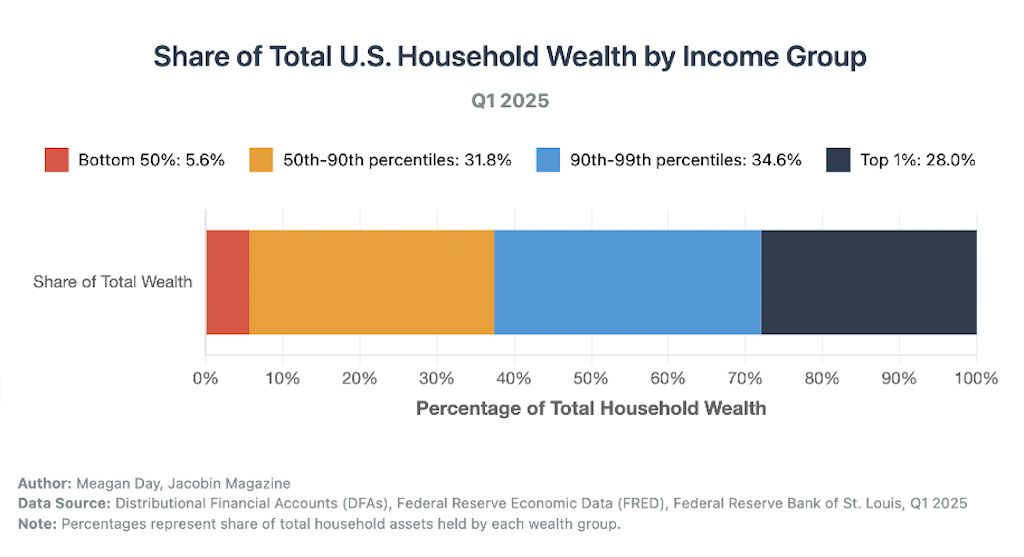

Simply put, the top 10 percent are able to spend so much because they have so much more than everyone else. According to the latest Federal Reserve data, the top 10 percent of US households by wealth control 62.6 percent of all household assets. The top 1 percent alone hold a staggering 28 percent of total wealth.

This concentration becomes even more stark when considering the other end of the distribution. While the wealthiest tenth of Americans owns nearly two-thirds of all assets, the bottom half of households, representing over 160 million Americans, hold just over 5 percent of total wealth.

Consumer spending is no insignificant matter; it accounts for 70 percent of the American economy. In other words, it appears that the main thing keeping Trump’s economy in decent shape at the moment is inequality itself.

When consumer spending is removed from the equation, the state of the American economy under Trump looks much weaker. Last month, the White House declared that “our nation is witnessing an unprecedented surge in manufacturing investments and job creation.” But on closer look, neither claim holds up.

Manufacturing employment has actually declined for several consecutive months, with a net loss of thirty-three thousand manufacturing jobs so far in 2025, while general manufacturing activity has contracted since March. As for the overall jobs picture, the August jobs report revealed the US economy added just 22,000 jobs total, far below expectations of 76,500. Unemployment claims have climbed to their highest level in nearly four years.

Meanwhile, credit cards are seeing delinquency patterns climb back to their highest since the early 2010s. Student loan delinquency rates have hit an all-time high now that payments have resumed. Auto loans and other forms of household debt are also experiencing elevated or record-high delinquencies in many regions and demographics. Credit scores are dropping at their fastest rate since the Great Recession.

The wave of missed payments is a telltale sign that people outside the top bracket are struggling financially. And of course they are: Inflation has made life noticeably harder for the bottom 90 percent of Americans in recent years, with rising prices for essentials like food, rent, and transportation eating away at paychecks and savings. The surge in living costs, fueled by both persistent core inflation and spikes in certain goods due to new tariffs, has made it challenging to cover basic expenses, let alone pay off debt.

If metrics like these were rightly understood as ultimate indicators of economic vitality, we’d be operating with a clear consensus right now that the economy is in bad shape. But the well-being of average people has never been a privileged criterion for measuring economic health under capitalism.

Right now, we’re looking at a split-screen economy. On one side, we have a world of abundance and ease, where money flows freely and financial decisions carry little weight. On the other, we have a world of scarcity and sleepless nights, where every dollar must be stretched and every expense carefully considered. An overwhelming majority of Americans see their reality reflected on screen number two, not screen number one.

For the top 10 percent of households, who earn $250,000 or more per year and who own 93 percent of all stocks, inflation makes little difference. Ground beef prices may be at an all-time record high, but a package costs the same whether you’re rich or poor. With the money left over after everyday items, this wealthy cohort is fueling a steady 5 percent annual increase in the luxury market, which is on track to hit nearly $68 billion this year. The top 10 percent are upgrading their kitchens, booking first-class tickets, and splurging on jewelry and hotels even as the rest of the country treads water or falls behind.

Meanwhile, the spending power of average Americans has declined as wage growth has failed to keep pace with inflation. So the bottom 90 percent are tightening their belts. They’re shopping in bulk, clipping coupons, skipping vacations, canceling subscriptions, and putting off big purchases like cars and orthodontics, according to the Wall Street Journal. Average people have stopped buying clothes and shoes that aren’t essential. They’re stressing out over bills, ruminating on their finances for several hours per day, and feeling anxious and depressed about money. There are hundreds of millions more people in this camp than the first one.

All told, the average American inhabits a completely different financial reality than the one represented by the top-line statistics. Despite the triumphant White House rhetoric, our country’s economy is failing by the metric that matters most, which is whether people who live here are able to meet their basic needs without backbreaking effort. If nothing else, there’s something deeply wrong with an economy where a few people have so much money that their spending habits mask how little everyone else has.