How National Self-Sufficiency Became a Goal of the Right

What looks like Trump-era economic nationalism has deeper roots. German nationalists of the 1800s and fascist leaders of the 1930s imagined power through autarky — national self-sufficiency — with consequences that stretched from tariffs to conquest.

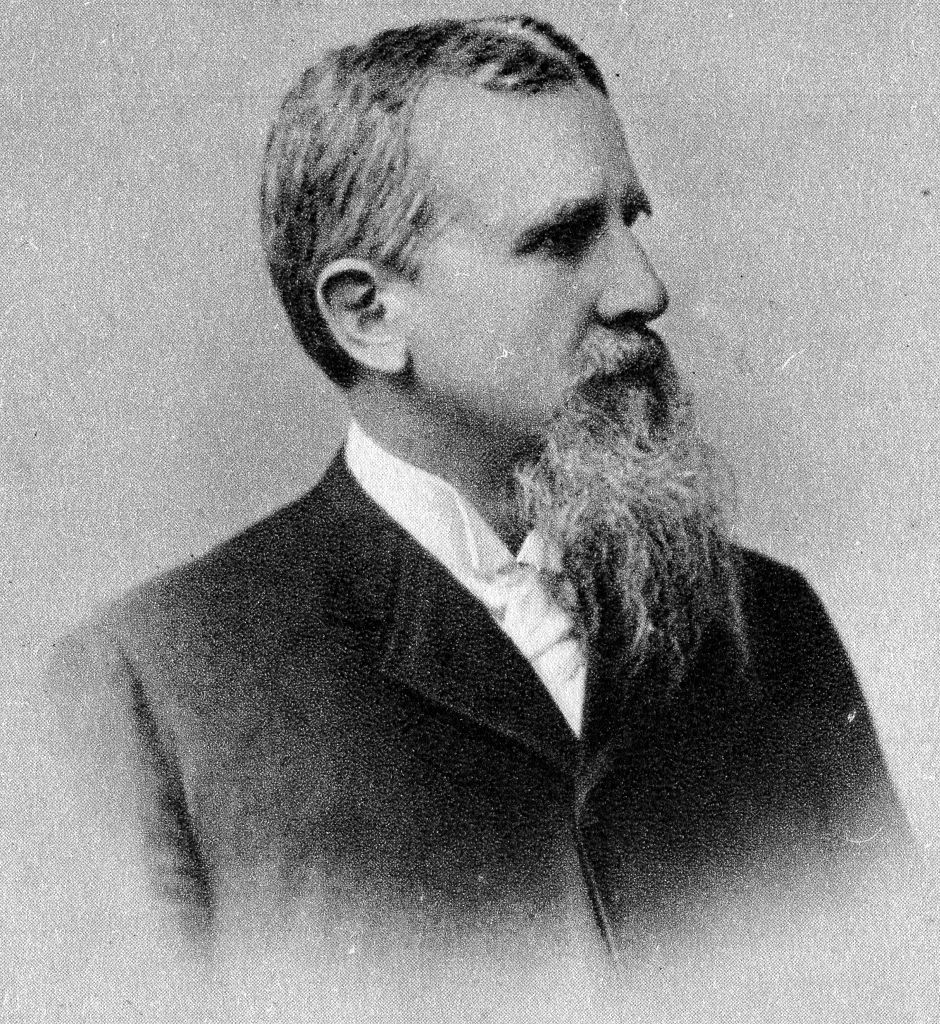

Friedrich Ratzel (1844–1904) was a German geographer and influential early proponent of autarky, or national self-sufficiency. (Ullstein Bild via Getty Images)

Although the “liberation day” measures of April 2024 were hardly a surprise, they still prompted a global stock market crash and volatility on the US bond market. They also exposed a rift among Donald Trump’s entourage. The tech tycoon Elon Musk, a short-lived addition to Trumpism’s libertarian wing, derided trade czar Peter Navarro as being “dumber than a sack of bricks.” MAGA ideologue Steve Bannon punished Musk’s deviation from the party line by jumping to Navarro’s defense and calling for the nationalization of SpaceX.

Navarro is, in many ways, an unlikely Trumpist: a former Democratic candidate and longtime proponent of free trade. Yet his 2024 book The MAGA Deal: The Unofficial Deplorables’ Guide to Donald Trump’s 2024 Policy Platform locates the root cause of inflation in America’s overextended supply chains — affecting everything from pharmaceuticals to Christmas decorations. Above all, he worries about the defense industrial base. Offshoring, he warns, undermines not only blue-collar jobs, but also the nation’s ability to “enter another world war.” Any dependence on China, whose autarky he admires, further threatens national security.

Musk’s retreat was more than a victory for MAGA loyalists. It also paved the way for Trump’s tariff regime to become a permanent feature of the global economy. It is only the latest chapter in a broader renaissance of protectionism that began in 2016, persisted through 2021, and has since shaped policies across major economies and trade blocs. But in an era of increasing state involvement in the defense industry, rearmament, imperial rearrangement, and violent land appropriation — much of it sanctioned by the Trump administration — there is clearly something more than mere mercantilism going on. We may have entered a new age of national self-sufficiency, better known as autarky.

Never Mind the Barriers

In Hayek’s Bastards: The Neoliberal Roots of the Populist Right, Quinn Slobodian argues that the rise of the political right emerged not as a form of resistance against neoliberal globalism but from within key factions in the neoliberal movement. Rather than framing these thinkers as “barbarians at the gates of neoliberal globalism,” they need to be understood as the “offspring of that line of thought itself.”

Many neoliberals did indeed turn to scientific racism in the 1990s, their interest in Herrnstein and Murray’s The Bell Curve being the mere tip of the iceberg, as Slobodian shows. But in terms of the origins of Trumpism, some may take issue with the sweep of the argument here. For one thing that he has preciously little to say about is autarkism. This silence is striking, given that autarky was always a concern for neoliberals.

The Austrian school economist Ludwig von Mises, who had a close relationship with fascism in its Austrian and Italian variants, was unambiguous in his verdict on the matter. Autarky was “the road to misery,” a path mired with noncompetitiveness, capital consumption, mass unemployment, and declining living standards.

Von Mises was aware in the late 1930s that the autarkist geopoliticians with their “military point of view” were calling the shots. Although he dismissed their protectionism as irrational — likening it to the unhygienic practices of “certain oriental ascetic sects” — he took their arguments seriously. He was hardly motivated by pacifism, however; his concern was the conservation of European power.

“Let us take care that we do not carelessly squander Europe’s advantage in the world,” he warned. Such an imperial critique of national self-sufficiency, incidentally, lives on in liberal responses to Navarro’s trade and security policies.

Pretty Vacant

Although it can claim antique roots, autarky does not describe a fixed set of policies or a school of thought. Autarkists have variously emphasized agricultural, industrial, and energy self-sufficiency, wage competition, and resistance to foreign influence over the defense-industrial base. Policies include protectionism of various stripes, from border controls to restrictions on foreign currencies.

Autarkism offers a more overarching fantasy than protectionism or neomercantilism: the achievement of a state of national self-sufficiency, including the capacity to wage war. Autarkists may argue in economic terms, but they are politically motivated: power trumps wealth.

Over the centuries, autarkism has attracted figures with quite different ideological commitments. Both Gandhi and Mao championed self-sufficiency, but the most obvious home for autarky is on the nationalist right. After 1945, Fascists like Jean-François Thiriart and Oswald Mosley continued to champion autarky.

In the late 1990s, the Russian neofascist Alexander Dugin hailed autarky in Foundations of Geopolitics as a “third way” in economics. In 2022, Vladimir Putin’s Russia revealed in that its economy had achieved a high degree of autarky — enough to sustain a military campaign in the face of Western sanctions.

Mussolini and Hitler were both driven by the autarkic fantasy. Indeed, there are important echoes of 1930s Germany’s trade politics apparent in 2020s America. Germany’s revival of economic nationalism drew strength from the school of “Geopolitik” — whose overarching aim was the conquest of more space for German settlers. It was in Geopolitik that autarkism’s anti–free trade and antiestablishment dimensions emerge in the clearest fashion.

A critic of Adam Smith, geographer Friedrich Ratzel (1844–1904) admired China for its self-sufficiency. He wrote in his 1897 Political Geography, “China’s reluctance to expand its trade relations beyond a narrow scope must be appreciated; it lies in the self-sufficiency that its geographical location and population allow it.” Ratzel’s concept of Lebensraum (literally, “living space”) would leave a lasting impression on Adolf Hitler and his movement.

Ratzel’s follower, the Swede Rudolf Kjellén (1864–1922), made autarky a cornerstone of “geopolitics,” a term he coined. He noted in his 1916 The State as a Form of Life that England’s hegemony depended on exporting commodities while importing raw materials. Highly developed economies like England thus often had negative trade balances, resembling “a man who has stopped working productively himself.” Industrialization, he warned, could result in dependency little better than those of “monocultural colonies” such as Mexico and Canada.

For Ratzel and Kjellén, the ideal was neither colony nor rentier state but autarky, in which the state produced both raw materials and commodities. Such a national economy could survive behind closed doors, particularly during times of war. Protectionism was a key tool, but so were “closed spheres of interest” secured through bilateral trade deals. Trade within a state’s territory, moreover, was to be fostered at the expense of foreign trade.

Other autarkist geopoliticians soon followed in Ratzel and Kjellén’s footsteps. Karl Haushofer (1869–1946) was the leading voice of Germany’s Geopolitik movement in the 1920s and ’30s. Entertaining links to almost all key members of the Nazi elite, he tirelessly promoted the view that Germany had been cheated at Versailles. Germany lacked not only territory, but rubber and oil, key resources for the waging of war.

When Haushofer fell from grace in the early 1940s, Nazi economist and entrepreneur Werner Daitz took up the torch of autarkism. Daitz envisioned a “soldier economy” that could feed and arm the Germans. He was surprisingly candid about the fact that the need for autarkism arose from “instinct” — indeed, from the “irrational.” Although liberal economics was long dead in Germany, he still framed it as a challenge to the establishment.

The Third Reich ultimately failed to establish full autarky. Synthetic oil production underperformed and Germany never achieved agricultural self-sufficiency. Hitler had concluded at an early stage that the needs of the country’s economy could only be met by territorial expansion.

Nazi Germany differs in many respects from 2020s America. Yet the parallels are striking. Both German and American autarkists articulate a critique of free trade that foregrounds national security, valorizes economic power, and is preoccupied with trade balances. Both understand autarky as a deliberately antiestablishment enterprise — a strategy for a nation that has been cheated. We can even find a certain level of admiration for Chinese autarky in both cases. Crucially, both see imperial rearrangement and territorial annexation as a legitimate strategy. What may look like a case of two right-wing movements converging on the same place may in fact be at least in part explained as a case of common ancestry.

Autarky in the US

Sometimes described as Germany’s second most famous economist of the nineteenth century, Friedrich List (1789–1846) styled himself as Adam Smith’s adversary. Skeptical of the benefits of free trade, he argued that industrializing economies required high tariffs on manufactured goods if they were to compete against more established economies. Whereas free trade was a principle for the good of the individual and of humanity, it left out the unit of the nation. Protectionism was likely to incur short-term losses, but it promised long-term gains.

List’s 1841 magnum opus The National System of Political Economy famously argued, contra Smith, that “power is more important than wealth.” Much less negative about the economic benefits of military spending than the Scottish economist had been, List argued that such expenditures were hardly unproductive. Under certain circumstances, land appropriation was a necessity for states. He noted that “a well-shaped territory” was “one of the first requisites of a nation” and the desire of acquiring it could “sometimes be the legitimate cause of war.”

As a nationalist and a proponent of a German customs union (Zollverein), List encountered fierce opposition. He was imprisoned for his views and fled Germany for the United States in 1825. Settling among the Pennsylvania Germans, he was soon noticed by American industrialists. When he returned to Germany in in the 1830s, it was in a diplomatic role — appointed by President Andrew Jackson.

It is not easy to place List on the political spectrum of the twentieth century or even of his own era. In many ways he was a liberal and an adversary of key figures within Europe’s monarchical order. He not only supported private property and the corporate form, he was also firm in his anti-socialism.

In Imperial Germany, List ultimately found a home on the Right. Crucially, it was List whom Friedrich Ratzel — Hitler’s inspiration for the conquest of Lebensraum — hailed in Political Geography as the “prophet” and as the man who had proven Adam Smith wrong. In 1943, List was immortalized in the Nazi-produced biopic Der unendliche Weg (The Endless Road).

Through his contact with the Marquis de Lafayette, the French aristocrat and revolutionary hero, List was introduced into the highest echelons of American politics, reportedly even making the acquaintance of some of the surviving Founding Fathers, including James Monroe. He had close personal exchanges with Henry Clay, then John Quincy Adams’s secretary of state.

List was influenced in the 1820s by the “American System,” the protectionist economic plan championed by Clay and Adams. But the exchange was not one-way: List contributed to the American System, writing interventions for a pivotal protectionist organization — the Pennsylvania Society for the Encouragement of Manufacturers and the Mechanic Arts. His fellow protectionists were well aware that they were relying on a foreigner to make their case. And yet it was precisely his foreignness that lent List his authority.

American nationalists — Trump’s trade hawks Peter Navarro and Robert Lighthizer among them — tend to cast List’s friend Clay as the father of American protectionism, writing List out of the story.

Yet List was never entirely forgotten. In 1943, even as the Nazis were cinematically enshrining him, Edward Mead Earle, one of the founders of the Office of Strategic Services, wrote that List had had an “important influence on the young United States” but was now, “by a curious turn of history,” empowering the Nazis. The émigré geopolitician Robert Strausz-Hupé likewise observed with some admiration that List had earned the respect of important American political figures. A few decades later, Strausz-Hupé would become an adviser to the proto-Trumpian Republican candidate Barry Goldwater.

For many years, autarkism remained at the margins of Republican politics, Reaganite protectionism notwithstanding. By the 1990s, however, List was revived by conservative critics of neoconservatism and neoliberalism — as an alternative to the economics of both Marx and Smith. The paleoconservative thinker and former Reagen aide Patrick Buchanan was the most prominent, though not the only, such figure.

Buchanan — whom Trump once endorsed as a challenger to George H.W. Bush — wrote at length about List in his 1998 The Great Betrayal. Unlike the classical liberals, who offered only “theory,” List, he argued, offered a “working model,” one proven correct by American experience. But in Buchanan’s telling, it was not the United States but China that now followed List. Beijing was using its trade surplus with the United States to upgrade its armed forces so they could reach America’s west coast. At the same time, Buchanan speculated about a possible breakup of Canada leading to US territorial enlargement.

No Future?

The current age of economic nationalism coincides with an era of violent land appropriation — from Ukraine to Palestine. Even where territorial borders have not yet been altered, there is a renewed acceptance of territorial annexation. Both dynamics intersect in the contemporary flirtation with autarkism.

List himself was aware of the dangers of stifling domestic competition through high trade barriers. For him, tariffs were a temporary measure, not an end goal. He was right, of course, about what later economists would refer to as infant-industry protection, which is why he has episodically appealed to the Left, too. But it is no surprise that List has been repeatedly taken up on the far right — from Buchanan’s paeans in the 1990s to Dugin’s endorsements today, amplified by publishing houses such as Imperium. List’s case reveals that the history of economic nationalism is not just one of common circumstance, but also of common ancestry.

The renaissance of autarkism, of course, has neither marked the end of GOP tax cuts, nor has it ended neoliberal trade policy everywhere. Germany’s Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) remains staunchly neoliberal in key aspects of its economic policy. AfD is committed to the WTO and keen to continue German trade with China and Russia. Some of this may be driven by the imperatives of an export-driven economy. But it also highlights that even in the 2020s, autarkism is only one option among several for the Right.