The Gilded Age Roots of American Austerity

Donald Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill isn’t just a modern assault on SNAP and Medicaid — it’s the revival of a 150-year-old playbook. From Civil War pensions to modern welfare programs, political elites have long moralized against need while rationing care.

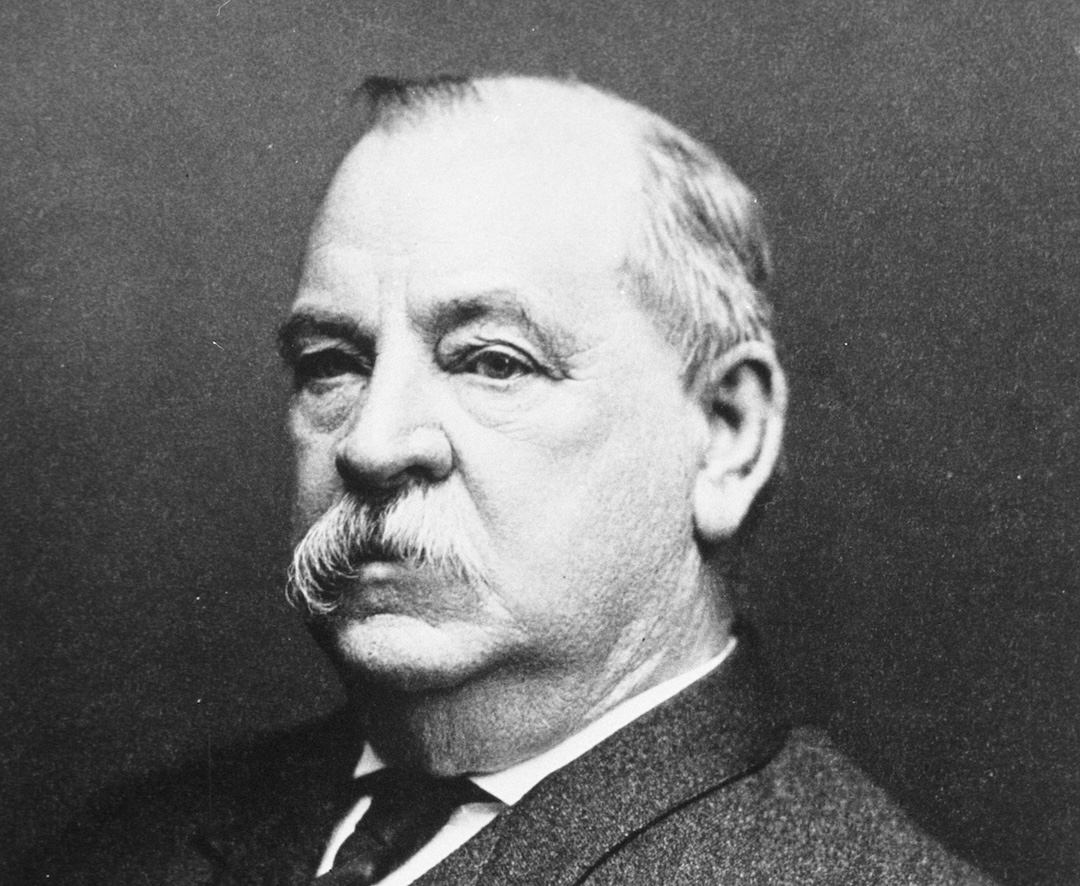

Portrait of the twenty-fourth US president, Grover Cleveland. (National Archives / Newsmakers via Getty Images)

The American welfare state has always been imperfect because it has always been incomplete — means-tested rather than universal, stigmatized rather than celebrated. Austerity is not just a matter of budget cuts or political whims but a built-in feature of this system, one that relies on the careful rationing of public provision.

Programs such as Social Security and Medicare — often labeled “entitlements,” a term that technically refers to legal eligibility but is frequently deployed to connote excess or unearned privilege — have proven more resilient in the face of perennial threats of defunding and privatization. Their durability stems in part from cultural notions of the presumed “worthiness” of the clientele and in part from the sheer number of Americans who depend on them and hold them in consistently high regard.

The other line on this two-track system runs through a populace equally sizable but regarded by many as unequally deserving: those low-income Americans who rely on Medicaid and food assistance programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). These programs have long been the targets of austerity measures, not necessarily through headline-grabbing slashes in funding, but through steady administrative erosion and rhetorical vilification. Medicaid currently serves about forty million people, a fraction of those who cannot afford skyrocketing health care costs.

The recently passed One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) marks the latest and most extreme iteration of this political logic, projecting the usual disdain for the poor onto a scale not seen for decades. The bill will cause an estimated seventeen million Americans to lose their health coverage through Medicaid and millions to lose their food assistance through SNAP. These devastating cuts free up funding for an Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) budget set to triple in size to $170 billion. The Congressional Budget Office forecasts that the bill will both reduce Medicaid spending by $800 billion and increase the national deficit to $3.3 trillion in ten years.

Paper Cuts for Punishment

As crude as it appears, the OBBBA will not bludgeon Medicaid and SNAP with anything as straightforward as a funding cut. Instead, the Republican bill will purge the rolls through the insidious instrument of paperwork, increasing the already weighty administrative burdens inflicted on claimants who deign to participate in the program. The result is the same: fewer participants, fewer beneficiaries, a hobbled anti-poverty program, widespread misery, and a redistribution of resources to the wealthy.

These burdens come in the form of creatively cruel work eligibility requirements. Such requirements have long been used to ratchet up the means-tested threshold at the entrance of every American welfare agency. Indeed, because they were baked into the organizations themselves, detractors already have a prefabricated dial at their fingertips to cull the number of recipients.

The OBBBA will introduce a number of administrative burdens into the Medicaid and SNAP programs. It requires individuals — rather than states — to submit applications for enrollment in plans subsidized by the Affordable Care Act, including citizenship and income documents. It ends SNAP’s automatic enrollment of school-age children in free lunch programs. It forces beneficiaries to prove their eligibility twice a year instead of once. It imposes work requirements on “able-bodied” food-aid recipients between the ages of sixty and sixty-four. And it eliminates information sharing between agencies that coordinate coverage across anti-poverty programs.

The OBBBA is laced with such burdens. They serve at once to choke and cloak: to make it virtually impossible for most eligible recipients to retain their benefits and to obscure the resulting harm by presenting the changes as a principled effort to sift the truly worthy and thrifty from the fraudulent and lazy.

Rather than attacking Medicaid or SNAP directly, the Trump administration targets their alleged violators. It insists, in fact, that the OBBBA saves these programs for the “truly needy.” An official White House page of common misconceptions assures Americans that “there will be no cuts to Medicaid.” The bill, it claims, actually

protects and strengthens Medicaid for those who rely on it — pregnant women, children, seniors, people with disabilities, and low-income families — while eliminating waste, fraud, and abuse. The One Big Beautiful Bill removes illegal aliens, enforces work requirements, and protects Medicaid for the truly vulnerable.

Austerity, of course, is nothing new. Nor is the reactionary assault on the nation’s beleaguered social welfare programs. Nor, for that matter, is the scapegoating of racial minorities and immigrants as a rationale for dismantling them. But while most scholars and journalists trace the origins of the political backlash to the New Right’s opposition to the Great Society, the playbook reaches back even farther — to the very origins of the American welfare state. That drama unfolded in the first Gilded Age, under another much-reviled president who served nonconsecutive terms.

From Warfare State to Welfare State

The modern American welfare state is conventionally seen as a post–World War II phenomenon, with important antecedents in the era of the New Deal — above all the Social Security Act of 1935. Yet its origins can be traced back to the Civil War and Reconstruction, when the federal government not only seized, liquidated, or nationalized the private property of rebels and crushed the slave regime but, in doing so, expanded its central administrative capacity. Integral to this state-building project was the US Pension Bureau, which offered monthly stipends to eligible Union veterans and their dependents.

Among those with claims to make against the federal government were the 184,000 veterans of the US Colored Troops — 144,000 of whom had been enslaved — as well as their lawful heirs: widows, orphaned children, mothers, and fathers.

From its modest beginnings in 1862, the Civil War pension system mushroomed over the ensuing decades. At its peak in 1893, the nation had nearly one million pensioners on the rolls. Pension expenditures soared to $157 million in the year 1893 (about $5.6 billion today), consuming more than 40 percent of the federal budget. By the turn of the century, three-quarters of all surviving Union veterans drew a pension. By the mid-1910s, cumulative pension outlays rivaled total Civil War expenses.

For nearly twenty years after the Civil War, the Republican-constructed pension system functioned as the third rail in post-Reconstruction American politics, not unlike Social Security today. Union pensions were so fundamental to the political identity of the Reconstruction-era United States that Republican lawmakers sanctified pension payments in the Fourteenth Amendment, the charter of national birthright citizenship in the United States. (The fourth section reads: “The validity of the public debt of the United States, authorized by law, including debts incurred for payment of pensions and bounties for services in suppressing insurrection or rebellion, shall not be questioned.”)

Pension applicants underwent extensive means-testing of a physical sort. They were scrutinized by federally deputized physicians, who would assign them a disability rating. The ratings were assessed alongside documentary evidence — military records, depositions, and so forth — and applicants were either denied or rewarded pensions in varying amounts. By 1890, there were more than 119 fixed rates of pay, graded according to the degree of physical disability. Medical examinations defied all efforts at standardization and proved notoriously inconsistent.

Still, for two decades after the war, Democratic candidates and policymakers rarely objected publicly to the increasing size and “generosity” of the pension system. That is, until the mid-1880s, when the Pension Bureau became a lightning rod of political controversy and polarized the electoral field. Pension politics made and unmade American presidents.

Weaponizing Welfare

Gilded Age critics of the Pension Bureau objected to the agency’s seemingly unstoppable expansion, which they viewed as draining the Treasury and incentivizing pauperism. It created, they argued, a nation of dependents, perverting the work ethic of its beneficiaries and subsidizing fraud and graft. The avatar of the anti-pension crusade was Democrat Grover Cleveland, president from 1885 to 1889, and again from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland campaigned on reforming the pension rolls to ensure their purity, vowing to strictly limit federal benefits to the most deserving.

In 1887, Congress passed the Dependent Pension Act, which would have simplified and expanded the pension system by granting a fixed pension to everyone who served ninety days. After genuflecting to the essential importance of pensioning “worthy beneficiaries” — as politicians across the spectrum still do today — Cleveland bitterly complained in his veto message that Union soldiers and families had already been compensated with generous military pay and that the current pension rolls were already full of dubious cases.

The nation, he insisted, could not afford to add more names to the dole. Such “liberality” to the manifestly undeserving was, in his view, an insult to American patriotism as well as a millstone around the neck of the Treasury. It would, the president argued, “stimulate weakness and pretended incapacity for labor,” putting a “premium on dishonesty and mendacity.”

During his first administration, Cleveland vetoed hundreds of pension bills — ranging from large reformist efforts such as the 1887 act to individual pleas for pensions that had already received congressional approval. In addition to squashing any and all legislative efforts, Cleveland appointed a Pension Bureau commissioner with a mandate to purge the rolls. Commissioner John C. Black expanded the newly created Division of Special Examinations and ordered its agents to investigate all pension claims for traces of illegitimacy to instill “a wholesome regard for the power of the Government into the minds of the criminal classes.” In 1887 alone, Black’s examiners investigated over 31,000 claims, referring “suspicious” claims to the Justice Department for criminal prosecution.

Cleveland’s internal assault on the pension rolls elicited an organized response from the most powerful civic group in the country. The Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), a veteran’s organization some-400,000-members strong, mobilized to oust Cleveland in the 1888 election, which the GAR made into a referendum on the Pension Bureau. Scholars attribute the election of Republican Benjamin Harrison, the passage of the 1890 Dependent and Disability Pension Act, and the subsequent expansion of the pension rolls in large part to the GAR’s efforts.

Backlash and Retrenchment

The dramatic increase in the number of pensioners provoked enormous public opposition, stoked by Democratic politicians and media outlets. Echoing Cleveland’s 1887 veto message, the New York Times crowed that “instead of saving veterans from the humiliation of pauperism,” the bill would actually “offer a large premium for professional pauperism, and the number of the unworthy who will receive its benefits will be so large that they will throw discredit upon all who share with them.” “Nothing can explain our tolerance of the present and prospective pension expenditure,” cried another detractor, “but socialism of an extreme and dangerous type.”

Cleveland rode this tidal wave back into the White House in 1893. “The lessons of paternalism ought to be unlearned,” he sneered in his second inaugural. Though all patriots must support the government, “its functions do not include the support of the people” (emphasis added).

Unable to abolish the Pension Bureau outright, Cleveland worked to corrode it from within. As he had during his first term, he appointed a hatchet man as the bureau’s commissioner and ordered him to systematically reexamine claims. Commissioner William Lochren immediately reversed a ruling from his predecessor that allowed minor disability ratings to be aggregated into a single, composite rating, rather than taking the greatest rating as the chief disability.

After this subtle but significant policy reversal, Lochren instructed a corps of twenty special investigators to examine pensions awarded under the Disability Act of 1890. He also introduced “credibility inquiries” designed to discredit witnesses who testified to a claimant’s disability.

“Without the restraint of special examination investigations,” Cleveland’s zealous commissioner warned in his 1895 annual report, “fraud would flourish and the dishonest practitioner and dishonest claimant would lead by far in the successful establishment of pension claims.”

Lochren’s bureau conducted over 40,000 investigations in the first year of his tenure. The Bee, a black newspaper based in Washington, DC, predicted that over 150,000 pensioners would lose their benefits owing to the commissioner’s decisions. The Bee also feared that, before his term ended, Lochren would make a “clean sweep” of all sympathetic officials in the bureau.

Means-Testing as Self-Sabotage

Cleveland’s dogmatic hostility to welfare has proved an enduring critique, in no small part because of its ostensible commitment to financial prudence and facial race neutrality. His practical efforts to erode the welfare state have similarly established an enduring model — one that combines backhanded praise with underhanded destruction.

Though rarely explicitly targeted by Pension Bureau critics, black pensioners found themselves at the bleeding edge of every conservative effort to reform the organization. Black claimants were far less likely to be admitted to the pension rolls than their white counterparts in the North. Once admitted, they received smaller pensions. Black applicants were far more likely to undergo special investigations, which not infrequently led to expulsion from the rolls as well as fines and imprisonment. This was especially true during the calculated purges under Cleveland, when thousands of black claimants were dropped from the only inclusionary federal program in the early days of Jim Crow.

Myriad reasons account for these racially inegalitarian outcomes — chief among them the physically invasive means-testing used to determine disability levels and the semiprivatization of that task through contracts with civilian physicians. This arrangement often benefited white Northern claimants while producing grim ironies in many Southern examining rooms, where former Confederate physicians — and, in some cases, former enslavers — evaluated the laboring capacities of former slaves on behalf of the federal government.

From the start, the Pension Bureau had been an experiment in civil citizenship — grounded in property and contract — rather than social citizenship, grounded in universal rights conferred by membership in the nation-state. As such, the liberal welfare regime that emerged relied on means-testing as a way to tailor benefits narrowly and limit their reach.

By the time Cleveland departed office, embittered and besieged on all sides, a grassroots movement was stirring up unrest among the agrarian and industrial classes. The Populist Party became the political vehicle for this principled anger, channeling the frustrations of the producing classes against the ownership class. For the first time since the 1850s, the partisan duopoly faced a threat from below.

The similarities between Grover Cleveland and Donald Trump extend beyond the superficial fact of their nonconsecutive terms — or, for that matter, their physiques. Both employed the rhetoric of worthiness and efficiency, anti-fraud and anti-corruption, as justifications for their austerity measures. Both used federal troops to discipline the working class: Cleveland sent in the US Army to crush the Pullman Strike in Chicago in 1894; Trump, more than a century later, deployed Marines and federalized National Guard units into the city of Los Angeles — this time not to break a strike, but to conduct sweeping immigration raids that targeted undocumented workers and sent a chilling message to labor leaders. And both did so in the name of economic noninterventionism and small government that serves only the “truly worthy.”

Means-tested programs have historically emerged from bipartisan compromise, but the problem isn’t compromise itself — it’s the balance of power that produces it. Without a strong, organized working class to force fair outcomes, these programs are designed to be narrow, conditional, and vulnerable from the start.

The historical irony ought to be clear: welfare programs that rely on means-testing are eroded by means-testing. This includes programs that have done immense good for millions of people, including Medicaid and SNAP. Means-testing ensures that society’s most exploited are also the most vulnerable to the state. It gives opportunistic lawmakers a ready-made mechanism for reducing welfare spending. All they have to do is reach behind the bureaucratic veil and turn the sacrificial savings dial to the right.

Our welfare state moralizes against need. It isn’t broken — it’s working exactly as it was designed to. Appreciating this history, and the essential meanness of means-testing, requires a parallel appreciation for the possibility of a more democratic, universal welfare state.