Money for Nothing

Why the modern financial sector is better at extracting rents than funding the future.

Illustration by Yann Bastard

At the time, it seemed like the fallout from the 2008 crisis would force a reckoning. The Great Recession had laid bare just how deeply Wall Street shaped — and distorted — the American economy. A housing bubble fueled by reckless lending and new financial products had burst, triggering mass foreclosures, a global credit freeze, and the worst economic downturn since the 1930s. Millions lost their jobs and homes, and anger at the banks that helped cause the crisis simmered. It seemed like time to question the central economic role we’d given the financial system.

Policymakers had something else in mind. In the end, they ensured the precrisis financial system was simply glued back together, with some modest guardrails put in place. A new consensus took hold: as long as Wall Street doesn’t crash the car again, it’s free to keep steering it.

But what does this arrangement mean for our economy and the people living in it? For some, it’s a system that deserves far better than the populist vilification it has received, as the financial sector helps our economy remain competitive. In this story, financial capitalists make daring bets on inventions and future productivity. They’re speculators, yes — but if systemic risks can be contained, the innovation their gambles enable is worth it.

A closer look at the data, however, casts doubt on this narrative. First, the expansion of the financial sector over the last fifty years has in many respects allowed wealthy financiers to become less speculative than ever. Instead, increased financial activity has permitted the richest asset holders to sit back and earn easy, safe returns without having to wager on actual productive investments.

Before World War II, financial profits largely came from loans that funded productive investment; financiers were gambling on businesses’ future output. Over the last half century, however, those returns have increasingly come from other sources: household and government debt as well as nonproductive business debt. Once packaged and resold, unproductive debt provides more reliable, less speculative sources of profit for today’s capitalists. Without having to rely on gambles on productive investments, financial profit-making at the top is perhaps better viewed as a form of rent collection than as speculation.

In many ways, rent-seeking is even worse than speculation. Beyond the crises it has created, there’s good evidence that financial rent-seeking has helped stall the broader economy. By making loans to households without boosting productive investment, the twenty-first-century financial sector temporarily props up consumption via household debt — but this ultimately leads to stagnant aggregate demand without meaningfully increased supply. Allowing the financial sector to continue driving our economy means persisting on this path. Taking stock of this reality is a key step toward charting a different way forward.

The Financial Sector Since 1980

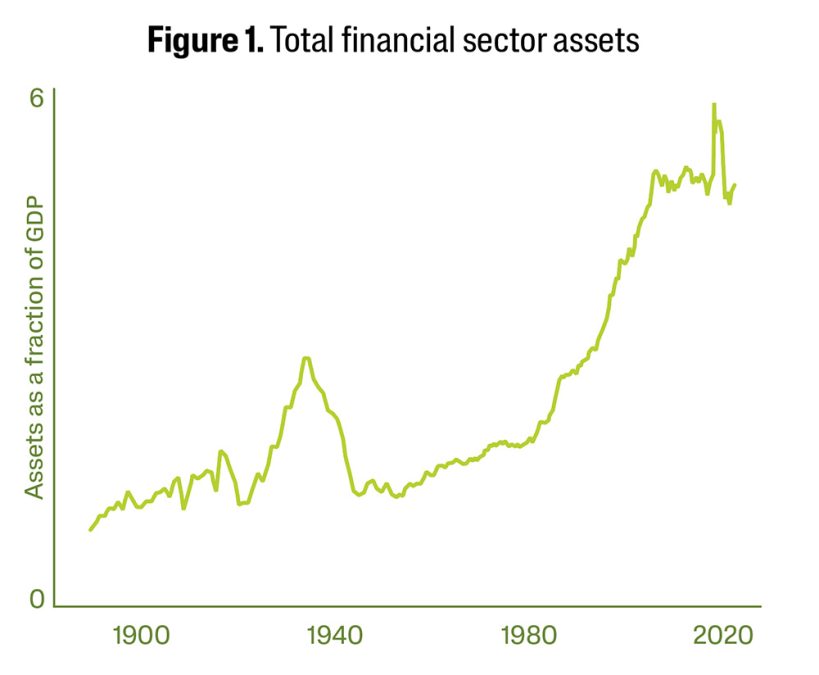

Figure 1 conveys the macroeconomic importance of the US financial system. It shows the total value of assets held by the financial sector, divided by GDP. Other than the boom-bust cycle of the Great Depression, the financial sector grew slowly until 1980. Then, immediately following Ronald Reagan’s inauguration, financial assets began to rise far more quickly than GDP.

This is one sense in which the financial sector is now more important than ever. Crucially, this is not a story of steady, inevitable financial growth over time, but rather a sudden rise brought about by changes in the 1980s.

Who actually owns these assets? Financial assets are the most unequally distributed form of wealth: about 75% are owned by the wealthiest 10% of Americans. And as several studies have shown, owning these assets lets the rich earn higher rates of return. In the United States, people below the 90th wealth percentile earn, on average, something like a 3% annual return on their wealth; this rises to 6.5% for those in the 90th–99th percentiles, and to over 8.5% for the top percentile.

On paper, these higher returns come from taking on more risk — from speculating. But this isn’t quite accurate. First, wealthy investors own far more than they can possibly consume in a given year. Since they don’t need cash immediately, year-to-year risk isn’t as relevant for them; they can afford to wait out fluctuations with the knowledge that, over the next decade, they’ll reliably end up with an 8% annual return once those variations average out.

Studies on Swedish and Norwegian households, where better-functioning tax systems allow us to observe top wealth, paint this picture more clearly. They find that across a variety of measures, wealthier investors reliably capture higher returns, even after taking risk into account. While US evidence is more limited, the broad picture almost certainly holds here as well; with internationally liberalized finance, anyone who owns $100 million and lives in a rich country is going to invest in similar portfolios, regardless of which side of the Atlantic they’re on.

Rich households, which can plan their finances across decades rather than between paychecks, are essentially guaranteed higher returns than the rest of us. Investors at the top simply hand over their portfolios to a manager, earn somewhere between 5% and 15% each year, and sleep soundly, knowing that this will average out. To me, this looks more like a rent than a gamble.

Understanding Intermediation

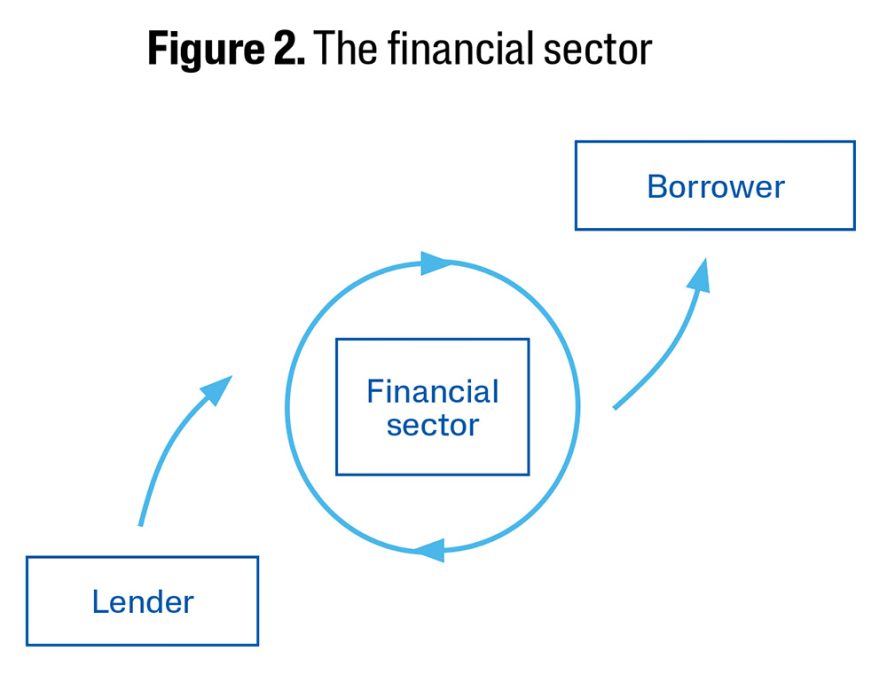

How does the financial sector make this happen, and what are the macroeconomic effects on the rest of us? It helps first to get a clear picture of what the financial sector actually is. Think of finance as an intermediary between a lender and a borrower: instead of a lender making a loan directly, they lend first to the financial sector, which lends in turn to a borrower. A financial asset is just a loan: the lender “owns” the promise of future repayment (with interest) from the borrower. Making a financial investment means buying an asset, which in essence means lending money to someone. Thinking in terms of lending and borrowing rather than asset purchases clarifies the essential economic activity underlying a financial transaction. Figure 2 visualizes this relationship.

The financial sector justifies its place in our economy by claiming that it serves as an essential intermediary to help money get to where it’s supposed to go. According to the World Bank, “Robust banking systems and capital markets efficiently flow funds toward their most productive uses.” The financial sector, in short, is supposed to channel money to daring entrepreneurs with good ideas but scarce cash. In this telling, calling it “speculation” isn’t disparaging — financiers view themselves as taking smart gambles, picking the borrowers who will put their money to the best and most profitable use.

It’s worth keeping this story in mind as a benchmark against which we can evaluate our actually existing financial sector. Unsurprisingly, the data don’t back the sector’s claims. To begin to understand why, let’s make the situation represented in figure 2 a bit more realistic.

Here the financial sector appears as a single entity — but the same depiction applies to a financial sector with many institutions inside of it. After a loan is made from a lender to a bank, the bank might lend the money to another institution within the financial sector. The money can circle around inside before it’s finally lent out to a borrower outside the system. In this institutional arrangement, the financial sector still plays the role of mediating between lender and borrower; it just spends some time moving the money around internally first.

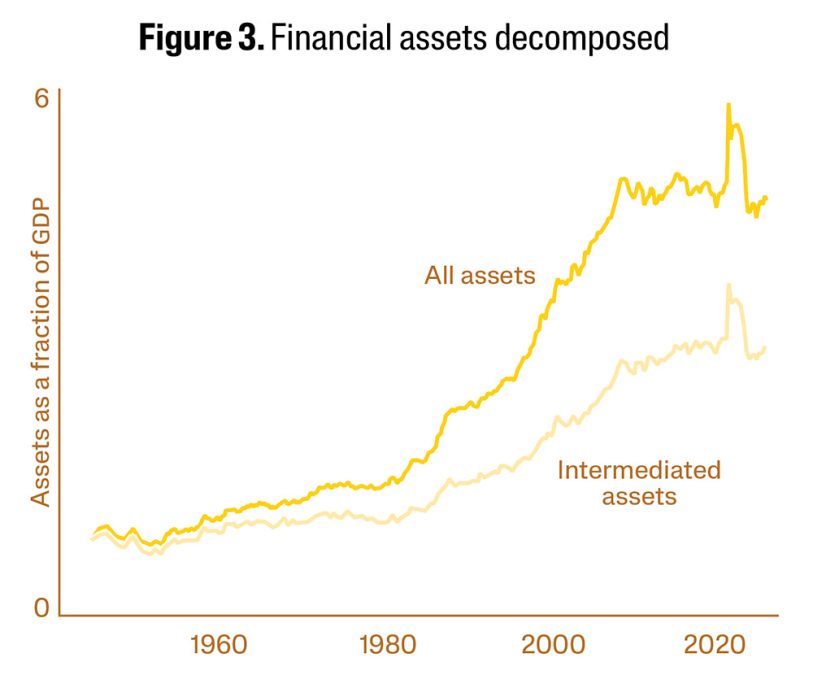

This clarifies that there are two components of financialization. First, the financial sector is lending more to the real economy: the arrow running from the financial sector to nonfinancial borrowers has gotten bigger. Second, the financial sector is lending more to itself: more money swirls around inside it. Figure 3 shows that both forms of lending have increased since 1980. The dark line shows total loans made by the financial sector; the light line shows loans made from the financial sector to nonfinancial borrowers. The difference between the two is thus loans made within the financial system.

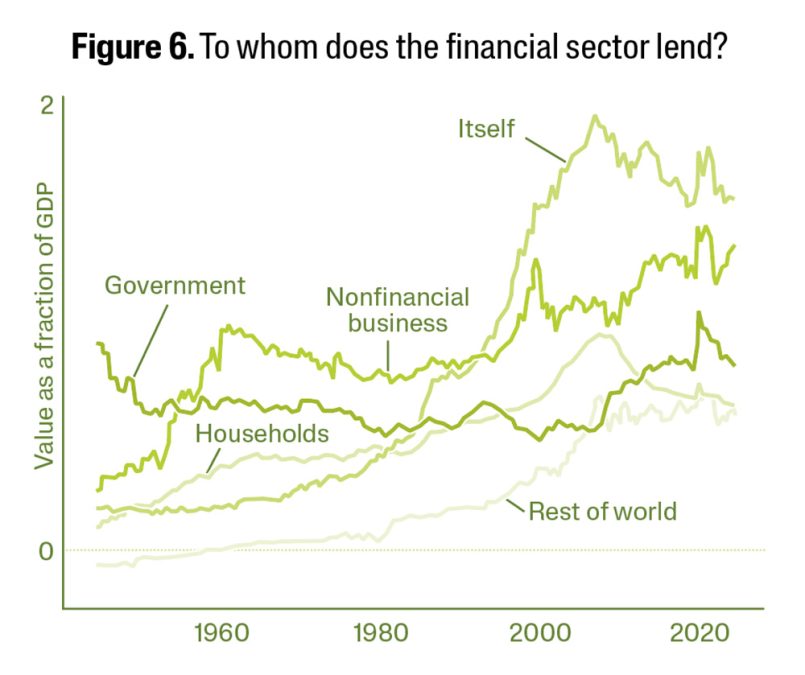

Before 1970, 90% of financial lending was to nonfinancial borrowers; since 1980, the financial sector has rapidly increased its internal lending. Today the financial sector makes 30% to 35% of its loans to itself — more than it lends to all nonfinancial businesses, for example.

This suggests an interpretation of twenty-first-century financial profit-making. When a wealthy household lends money to a financial institution, its 8% return results from the financial institution’s ability to do something profitable with the money. But a large part of that profitability comes from lending the money to other financial institutions. There might be some real economic activity backing it at the end of the day, but in the meantime, some of the profit from the loan just comes from the time it spends bouncing around inside the financial sector.

At first glance, it’s hard to see this as “flow[ing] funds toward their most productive uses.” But could it be? It’s possible that the ever-growing cycle of intrafinancial lending is making the financial sector more efficient. The first financial institution in the chain might be well positioned to borrow money but less able to figure out to whom it should be lent. Perhaps it’s better off lending to another financial institution instead, one that’s in closer contact with borrowers in the nonfinancial economy. In theory, the chain of internal lending could be precisely the machinery that the World Bank hopes will efficiently disburse funds.

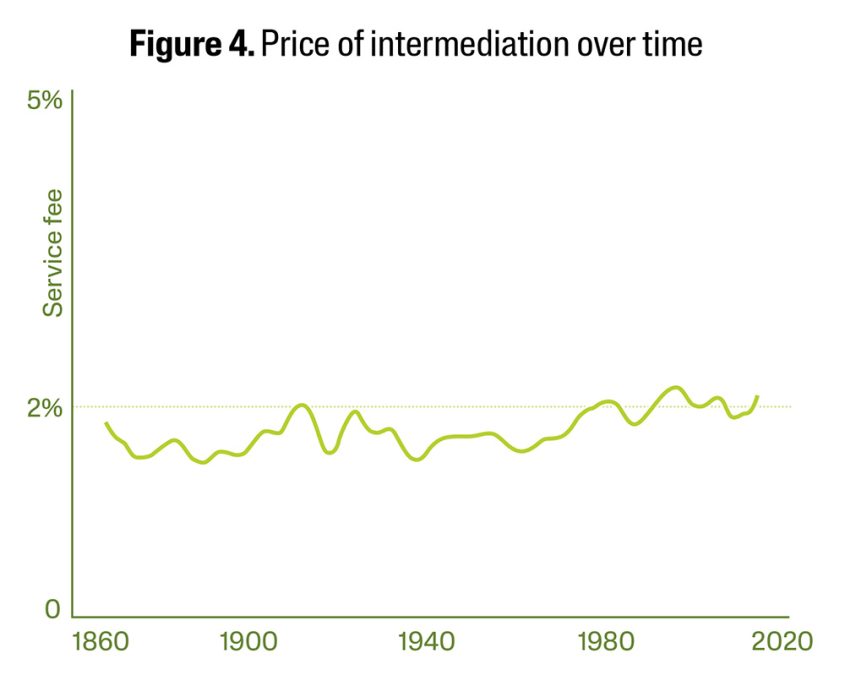

One way to evaluate this claim is to treat the financial sector like any other business. It provides a service (sending money from lenders to borrowers) and charges a fee for that service (the profits that accrue to financial institutions along the way). As the economist Thomas Philippon points out, if the financial sector has truly become more efficient, it should be able to provide the same quantity of services at a lower cost. Figure 4 shows that, unfortunately, this isn’t the case.

In 1885, the financial sector charged two cents for every dollar that it intermediated between nonfinancial lenders and borrowers. In 2015, it charged the same two cents per dollar. Philippon finds that this is accurate even after adjusting for the quality of intermediation provided. In the financial sector, 150 years of technological advances haven’t been used to send money from borrowers to lenders any more cheaply. Instead, those efficiency gains have allowed financial institutions themselves to claim higher profits.

This is one piece of evidence that financial intermediation isn’t as economically useful as it claims. But there is a second — and perhaps more relevant — way to evaluate finance’s economic impact. This involves looking at the money the financial sector does lend out to the real economy. Where does it go, and what does it do? Has increased lending boosted productive investment?

Lending to the Real Economy

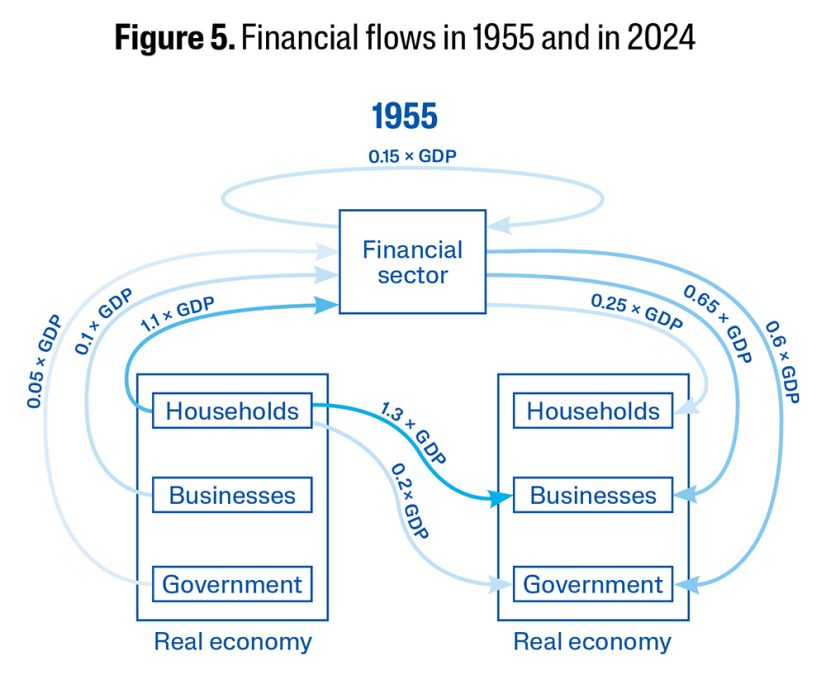

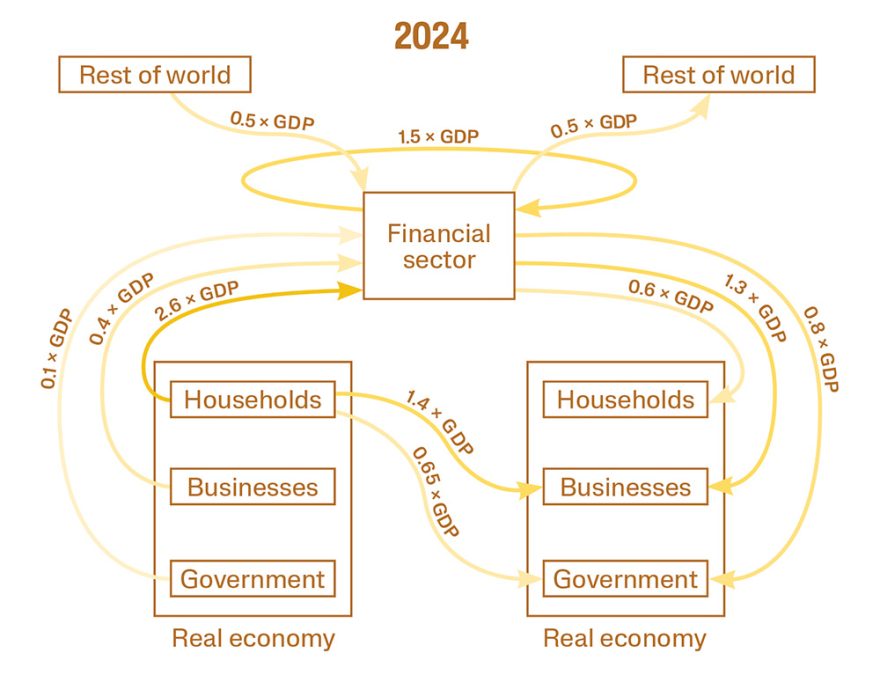

One-third of the financial sector’s loans stay within the sector, but what about the loans that get made to the real economy? Let’s split the nonfinancial domestic economy into three parts: nonfinancial businesses, households, and the government. Figure 5 shows the full movement of funds between the financial sector and the real economy; Figure 6 shows how this has changed over time. As we’ve already seen, the financial sector lends ten times more to itself today than it did in 1955. This internal lending increased rapidly after 1980; the financial sector now lends more to itself than it does to households or to nonfinancial businesses.

Most loans made to the financial sector come from households — and again, mostly from the top 10% of them. On the flip side, the loans that the financial sector makes to the domestic real economy end up in three places: about 22% go to households, 30% to the government, and 48% to businesses.

What do these loans do? Let’s take each sector in turn.

Nonfinancial Businesses

First consider the loans made to businesses. These comprise almost half of the financial sector’s nonfinancial loans; households also lend an equivalent amount directly to businesses via stockholding (see Figure 5). These are precisely the loans that are supposed to benefit the real economy by allowing firms to invest in productive projects. But crucially, this doesn’t seem to be happening.

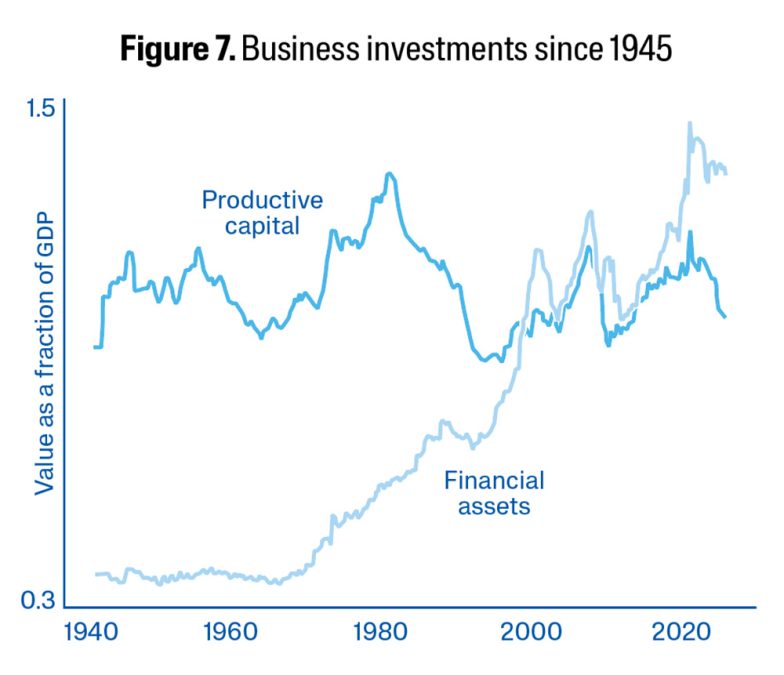

Figure 7 shows the composition of investments made by the aggregate nonfinancial business sector since 1945. Before the 1970s, business investment was almost entirely in what’s defined as productive capital (think equipment for a factory or a research laboratory). Loans to nonfinancial businesses have increased, but these businesses haven’t used the extra funding to grow their stock of productive capital (the dark line). Instead, they’re buying more financial assets (the light line). Taken together, nonfinancial businesses currently own more financial assets than they do productive capital. They’re seeking returns from owning these assets rather than from production.

Several economists have begun worrying about this phenomenon; former Treasury secretary Larry Summers christened it “secular stagnation” sometime around 2013. And this isn’t a uniquely American story. Since 1980, capitalist countries across the world have liberalized their financial sectors, and similar trends among nonfinancial businesses have followed. One study by a team of economists from the University of Chicago and the University of Minnesota finds that indeed, since 1980, corporations have used increased profits to buy financial assets rather than invest in production.

Households

The link between financial lending to households and productive investment is even more tenuous. Here the financial sector’s claim to usefulness would be that it provides needed cash to households, enabling purchases that keep people on their feet while maintaining aggregate consumer spending. But what do these loans actually do?

First, financial loans to households are, in essence, rich households lending to everyone else. In the flow of loans from households to the financial sector, it’s mostly the top 10% doing the lending; in the flow of loans from the financial sector to households, it’s mostly the bottom 90% doing the borrowing. A recent paper by the economists Atif Mian, Ludwig Straub, and Amir Sufi disentangles the web of internal financial sector flows to reveal that rich households’ financial assets are ultimately claims on the debt of the bottom 90%.

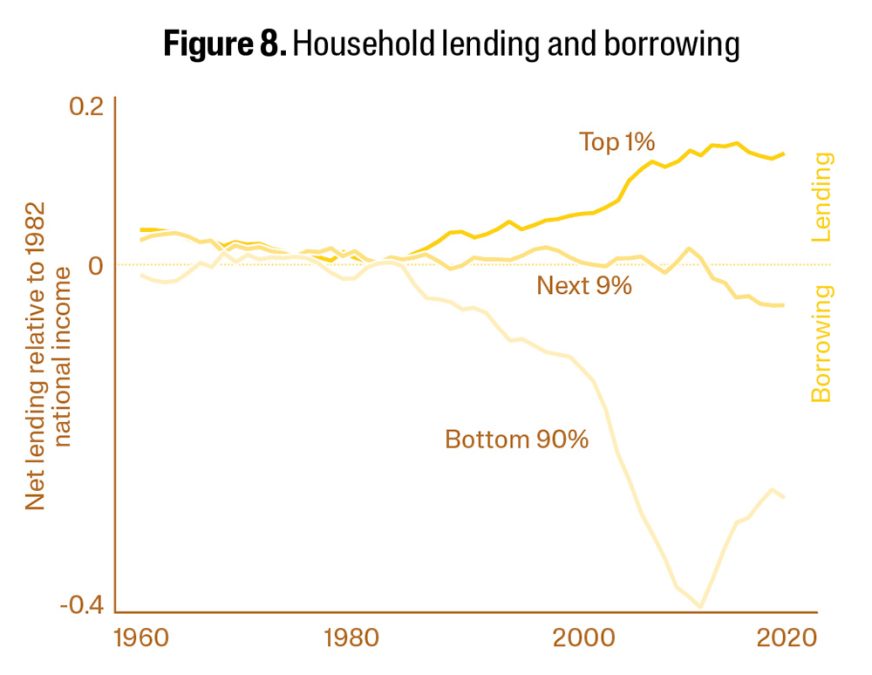

Figure 8, taken from that paper, shows lending positions between the different groups of households from 1960 to the present. Since the 1980s, the top 1% has become a net lender to the bottom 90%. One of the main contributions of the modern financial sector has been to facilitate this lending.

What does the increase in household borrowing mean for the macroeconomy? First, it’s hard to call this financial flow productive. About 70% to 75% of financial lending to households is in the form of mortgages; 20% is consumer credit. Mortgages would be productive if, by increasing the number of people buying homes, they spurred the construction of housing. Famously, however, increased mortgage lending only raises the prices of existing houses, without encouraging new construction.

Mortgages and consumer credit might be indirectly productive in another way: they allow households to spend more (increasing aggregate demand), which pushes businesses to produce. At best, this is a more roundabout claim of usefulness. Instead of the financial sector sending money directly to productive uses, we’re relying on it to boost consumer spending in a way that will trigger productive investment.

However, even if the goal were to boost aggregate demand, doing so with household debt is largely self-defeating. Another paper by Mian, Straub, and Sufi demonstrates why. When those in the top 1% lend to the bottom 90%, they temporarily boost aggregate spending: the wealthy household that lent the money wasn’t spending it, and now it goes to someone who will. But when the loan comes due, the money plus interest makes its way back to the top. The indebted household has to cut spending to pay back the loan; the rich household receives the money but doesn’t spend enough of it to make up for the debtor’s cuts. If you give an extra dollar to someone worth $10 million, they’re not going to spend it.

In the longer term, the loan is really a transfer from the poorer to the richer household. Because richer households spend less out of new earnings, aggregate demand will slump.

Keeping aggregate demand up, then, requires more household debt, since many households’ labor incomes are stagnant. This is one reason why economists often find that increases in household debt come with temporary bumps in spending, followed by medium-term slumps. In short, debt is a poor substitute for reliable income. This is nonetheless the strategy our financial sector pursues: propping up consumer spending with household debt rather than providing funds for investments that would meaningfully increase supply.

Government

Finally, the financial sector also sends almost a third of its intermediated loans to the government (of which 80% go to the federal government and 20% to state and local governments). The appeal to financial lenders is obvious: the US government provides a safe, guaranteed 4% return, backed by the power of the state and the promise of its continued existence.

Donald Trump’s second presidency, of course, is introducing plenty of uncertainty, but this underlying dynamic is still largely in place. The yield on ten-year treasuries still tracks the Federal Reserve’s interest rate; viewed from a longer historical perspective, there’s no obvious break in this relationship yet. Higher rates on long-term treasuries — 4% today compared to 2.5% before COVID — are due to the Fed’s rate hikes to control post-COVID inflation, not to Trump’s policies. The big picture is that financial markets continue to believe in the reliability of Washington in the long run. With these safe loans, financiers are opting for the guaranteed return that US state power provides instead of gambling on businesses’ output.

As with loans made to businesses, whether these loans are economically useful depends on what the government does with them. But here the appetite for public debt provides an opportunity. In a sense, the financial sector is partially offering to return the keys to the economic car to the government. When financiers and businesses choose the safe returns offered by US sovereign bonds over the risky work of inventing and building, they’re making the government an implicit offer: “Take this money and do something useful with it — just pay us 4%.” Unfortunately, Washington rarely makes good use of this opportunity.

Taking Stock

Then the project of financial liberalization began gaining steam in the late 1970s, it made two promises. The first was that increased financial transactions would help people and companies hedge their risks, smoothing out volatility. The second was that a liberalized financial sector would spur innovation and increase productivity by sending more loans to better places more efficiently. Almost 50 years later, we have enough evidence to evaluate the results.

The 2008 global financial crisis made it clear that financial liberalization hadn’t quite delivered on its first promise, to put it mildly. The financial sector does allow the wealthiest asset holders to hedge their risks. But the rest of us rely primarily or exclusively on labor incomes, which are the most volatile for the lowest-paid workers and which financial markets aren’t smoothing out. This is to say nothing of the spectacular risk to which financial liberalization has exposed us. Since 2008, the policy establishment has largely recognized this last fact. But it has ignored a more subtle and perhaps even more worrying phenomenon: the financial sector has mostly failed to deliver on its second promise, too.

Finance does not seem to be channeling increased funds into productive investment. Instead, much of the post-1980 surge in financial lending has gone to secondary markets, as financiers earn profits from lending to one another. This internal lending hasn’t made intermediation any more efficient. Meanwhile, half of all intermediated loans either go to governments, where state power backs guaranteed returns, or to households, where credit props up housing markets without driving real growth. These loans have, at best, a tenuous connection to productivity. And the loans that do reach businesses are mostly used to acquire financial assets, not to fund innovation or production.

Much of today’s private sector prefers collecting financial rents to channeling credit toward productive investment. Yet with numerous crises upon us, we have a long list of places where that investment is sorely needed. Political energy is, while not coalescing, at least swirling around this observation. The Green New Deal and renewed interest in industrial policy on the Left, calls for a “liberalism that builds” from the center, and Trump’s purportedly pro-manufacturing tariffs all demonstrate frustration with our stagnant supply side. Recognizing the liberalized financial sector as a key culprit in that stagnation is one conceptual step toward focusing this frustration.

Going forward, the Left should address the failure of the private sector to invest and to innovate. This will require policies that explicitly manage the allocation of credit. We should move beyond a single aggregate interest rate to a more deliberate approach — one that uses incentives and regulations to guide capital toward productive investments and away from rent-seeking. We should also consider more productively tapping into the global appetite for US government debt, which allows the state to finance large-scale public investments directly.

Critics will raise the usual objections: Why would the state be any better at directing credit than the private sector? But after half a century of trying the alternative, the evidence is clear. Private finance has not delivered on its promises of innovation and growth. It’s past time to look for something better.