Making Expensive Cities Into Union Towns

California boasts some of the most expensive cities in the country. Union organizing can help workers afford to live in those cities.

Sharp Coronado workers celebrating their NLRB representation election win. (SEIU-UHW)

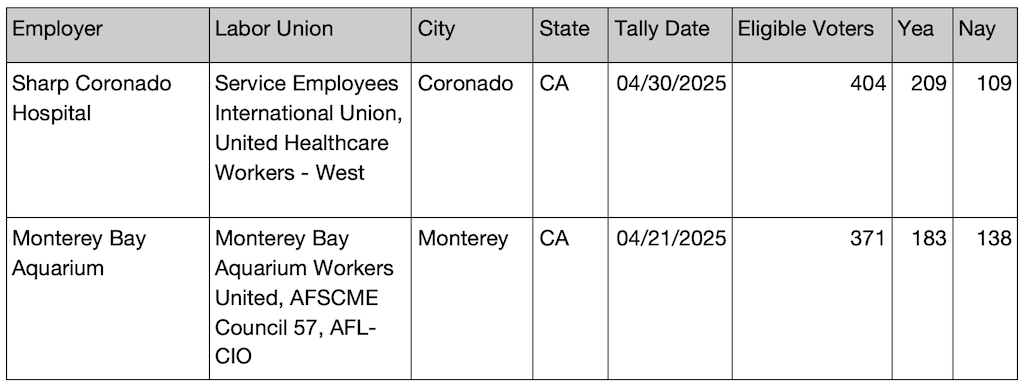

On April 30, 404 workers at the Sharp Coronado Hospital in Coronado, California, voted to join the Service Employees International Union, United Healthcare Workers West (SEIU-UHW), the largest NLRB representation election win of the month of April. For SEIU-UHW, this victory represented another milestone: the organization of the last acute care facility in the Sharp system.

SEIU-UHW has rattled off a slew of large-unit victories in this system, beginning with victories for 1,600 workers at the Sharp Grossmont Hospital and Sharp HospiceCare in 2023. In April 2024, they won certification for 1,100 workers at the Sharp Chula Vista Medical Center, and in July 2024, they did the same for 2,000 workers at the Sharp Metropolitan Campus. Together these victories have added more than 5,500 members to SEIU-UHW’s rolls. (Full disclosure: SEIU-UHW is a financial supporter of the Center for Work and Democracy, where I work.)

Dulce Armendariz, co-organizing director at SEIU-UHW and lead organizer of the Sharp campaigns, credits a series of “calculated risks” that the union took for the campaigns’ success. One such risk was a willingness to go public earlier than they were used to:

When we’re doing our organizing campaigns, we usually want to keep them underground as much as possible, so that we don’t trigger the boss campaign sooner than we’re prepared for it. But taking into consideration the size of these hospitals, we started having union mixers, where we’d turn workers out. These were in public places, pizza shops. We started to build a foundation of support there. . . . We’d hold these monthly, and the week following a union mixer is where we’d see a huge growth of union support across the hospitals and new breakthroughs into departments where we didn’t have support. . . . The union mixers kept growing in size, some over a hundred workers, and we’d train every worker there to go back and have union conversations with their coworkers. We could spend our days doing house visits, but you’re not going to be able to activate hundreds of people in the same way as we were able to in one day.

Like many unions, SEIU-UHW typically files for a representation election with the NLRB once they have gained supermajority support, understanding that a concerted anti-union campaign from the employer might whittle away support before an election. In the Sharp campaigns, by contrast, they were willing to file slightly before they reached this point, but still with a solid majority, on account of the quality of leaders that were being developed.

SEIU-UHW has also activated and empowered their members to take part in their campaigns. For a few years now, they have run organizing boot camps, where they train members to become union organizers. About 500 members have completed these boot camps, and once trained, they can be deployed on organizing campaigns and compensated with lost time payments from the union. Typical deployments are for two-week periods, but some members have been sent on three-month assignments, and some eventually take on turf and transition into staff organizers.

This was certainly the case in the Sharp campaigns, where member organizers were involved in union mixers and took on organizing turf. According to Armendariz, “It’s well-known that there’s a shortage of organizers throughout the labor movement. By training up members, we can help address this shortage and also give membership ownership over building their union.”

Political Campaigns and Organizing Gains

Sharp Grossmont workers first expressed interest in organizing to SEIU-UHW after the union had reached out to them for support for AB 204, which gave retention bonuses to health care workers. SEIU-UHW is a powerful political player in Sacramento, thanks partially to the fact that 40 percent of its membership contributes voluntarily to SEIU’s political action fund — the highest percentage of any SEIU local.

Using this political power, they also pushed SB 525 through the California legislature in 2023, which raised the minimum wage for health care workers in the state to $25 an hour. After some delays, the bill became effective in October 2024.

For SEIU-UHW, such political work is not an adjunct to their organizational mission but central to it. The union was the key institutional backer of the Fairness Project, an organization that has run ballot initiatives to raise wages, stop predatory payday lenders, expand health care access, secure paid time off, and more around the country. The Fairness Project has won thirty-two of the thirty-four initiatives it backed, raising working and living standards for roughly 18 million people. According to communications director Nathan Selzer, members are very proud of the national impact their union has made through this work.

Such pride has translated into both member involvement and organizing interest from outside the union. In the hallways at the union’s big executive board meetings stand large display boards outlining how well different “pods” (groups within the union organized by facility and geographic region) are doing in meeting their organizing goals. Metrics include how many people have been trained and deployed on organizing campaigns, how many members have contributed to the SEIU’s political action fund, and so on. According to Selzer, these boards indicate that their union is “unabashedly about results. There’s a lot of talk out there, but at the end of the day, we need to know what you are doing.”

Dream Jobs Where the Rent Is Too High

The second-largest win of the month was at the Monterey Bay Aquarium (MBA), where 371 workers voted to form their union, Monterey Bay Aquarium Workers United, with American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) Council 57. The drive started with one worker reaching out to Unionize California, a service of the California Federation of Labor that connects workers interested in organizing with the relevant unions — akin to the work of the Emergency Workplace Organizing Committee but for the state of California.

That employee was put in touch with Shane Anderson, organizing director of AFSCME Council 57 and the lead staff organizer on the MBA campaign. Inroads were quickly made into the animal care department, the largest at MBA and in many ways the face of the aquarium.

“When you think of the Monterey Bay Aquarium, you think of people who take care of the animals,” Anderson told me. “Often these are viewed as prestige jobs. Having their support was essential to win, and to build a truly representative union from across the aquarium.”

With Monterey County being the fourth–most expensive place to live in the United States, wages and affordability were understandably at the top of the list of MBA workers’ concerns. “A lot of people dream of working at the Monterey Bay Aquarium, but those who do often can’t afford to live in Monterey,” Anderson said.

Workers were frustrated with management in other ways: Samantha Parzuchowski, senior product manager in the Technology and Marketing Department, said that many employees want a “seat at the table,” as they have seen a lack of transparency from MBA leadership over large decisions. They also want improvements to their benefits package. Parzuchowski spoke personally to this:

Last year, I was diagnosed with cancer, and I had to get two surgeries. And I only had two sick days. . . . My manager worked out a solution with me and made sure I felt supported, and I want that for everyone. People who are sick and need to take time off should be able to take it.

With a strong base of support across the aquarium, the campaign went public on January 14. As with many cultural institutions, MBA management was publicly quiet about the announcement, but union workers say that privately they hired union-busting PR firms and attorneys and retaliated against workers being illegally recorded at union town halls. On the eve of the election, the associate director of the aquarium even put out a video pleading with workers to vote no.

In spite of the intense anti-union campaign, MBA workers won their union 183-138 on April 21. Parzuchowski believes that the diligence of worker-leaders, who sought one-on-one conversations with every single worker at the aquarium, was key. But she also cited the example of other cultural institutions: the union victory of Shedd Aquarium workers in Chicago in November 2024 was still fresh as MBA workers voted in April. Parzuchowski said that MBAWU is now looking “to build a future together focused on workers and the ocean. This win means we will have a seat at the decision-making table, a say in how our work is valued while we continue to support the mission of conservation we all believe in.”

Anderson is confident that with victories like those at Shedd and MBA as examples, we’re going to continue to see workers at large cultural institutions organizing, especially given national political developments.

The Trump administration has if anything galvanized many workers who want to do something in their communities that matters. And what better way to do that than to make their workplace a better place to be. . . . A bad boss is a good organizer, we always say, and Trump is the ultimate bad boss.