Enzo Mari (1932–2020)

Italian designer Enzo Mari insisted that design wasn't a game or a hobby, but a battle over the production process itself. His "design-it-yourself" encouraged workers to reclaim their ability to think for themselves — and not just execute other people's plans.

Enzo Mari in 1974. (Wikimedia Commons)

In a 1991 interview for Italian public broadcaster RAI, Enzo Mari discussed how he sought to distance himself from the “ludic” trends in contemporary design. Speaking in his typically stern tones, he insisted that design bears more resemblance to war than it does to playing games.

After his scenography studies and a few exhibits as a kinetic-programmatic artist, Mari’s first steps had in fact been in the world of games and children’s publishing. Yet, as we shall see, his participation in the Italian kinetic art movement, which art critic Lea Vergine defined as “the last vanguard,” would decisively mark the way he thought about design.

This experience would also forge his critical vision of the applied arts: too politically committed to obey the market, but too little so to change the shape of the world. But his dismay at this fact wasn’t enough to make him reverse course and find a space in the less “alienated” world of art.

Throughout his life Mari, who died on October 19 aged eighty-eight, remained an indignant figure in a creative and professional context that he wanted to be so different. Alessandro Mendini defined him as “design’s conscience.” GWF Hegel might have said: an unhappy consciousness.

Button-Filled Rooms

But back to games. In the 1960s, Mari and his first wife Leila designed a series of children’s books, which portrayed the cycles of nature without the help of words. The Apple and the Butterfly told the story of a caterpillar that hatches and grows in the core of an apple. Then comes its metamorphosis into an adult with wings, its hovering through the trees, and its pollination of a flower — thus leading to a second apple. The cycle of life, from one apple to another, is broken down into its stages, and portrayed with a style of illustration that is sparing with both details and colors.

In the first books there is a recognizable tendency to economize with form, something that would become the stylistic signature of Mari’s entire career. In this, there was no echo of a modernist “less is more,” in which the formal “less” opens the way for “more” functionality and efficiency.

In Enzo and Leila Mari’s works, the stripping back of detail is only an attempt to get to the heart of things, without any gain at some other level. Speaking of the design of these books, Leila Mari referred to a simplification strategy tailored to children’s inexpert gaze — one that sought to “make the real truer than the real.” In short, this was a digging effort, seeking out an essence which is not metaphysical so much as a tangible and hidden architecture of things.

In the mid-1960s, Mari made his debut as a product designer. The design of “Putrella” [in English, “girder”], marked the beginning of a lightning-fast career made up of over a thousand objects and many projects in collaboration with the greatest Italian firms of the era.

These were the years of the economic boom fueled by the Marshall Plan, in which Italy left behind the old agricultural economy and became a power on the world stage. Manufacturing industries were prospering; they brought new materials into the production process, tried out experimental techniques and involved designers, artists and writers in the various phases of fashioning objects.

As Mari was well aware, this wasn’t a revolution. Rather, it was a phase of economic expansion that transformed all culture into an industry.

Mari soon understood that there was not much to celebrate — that all of us, artists and workers, are part of the capitalist division of labor. As he put it in one of his last interviews, “For fifty years I’ve been working in the button-filled rooms where the commodity is shaped. And I’m the only one who’s against commodities.”

This dissident stance never turned into outright refusal. Rather, it materialized in an effort to “smuggle moments of research and stimulating contributions” through the holes of the net of commissions and production.

The first such moment was the aforementioned Putrella, a tray designed for a domestic interior whose name and form alluded to the metal joists used in the construction industry. This was an attempt to catapult the toughness of the world of work, left unaltered by rising living standards, into the colorful, soft, cozy bourgeois interior.

The story didn’t quite go as expected though — for bourgeois aesthetics took over, and Putrella became a limited-edition design object sold at a high price.

Reorganizing Work

Mari was familiar with the organization of manufacturing work — that is, the division between those who planned and those who produced, and the alienation of having to obey a design introduced by serial production. Throughout his whole career he would reflect on the broken relationship with artisan labor, seeking to understand how this latter could be given back its autonomous capacity.

Yet, this effort was not entirely successful. In 1973, Mari involved an artisan workshop in producing a series of ceramic objects. He asked the workers to interpret the design as a “rough outline” and not to worry about imperfections. But upon visiting the workshop, he found that the artisans had kept the initial models in front of their workstations, measuring any irregularities so that they could reproduce the models exactly. The romantic Mari had to take a step back and acknowledge that giving up his own supervisor role had little impact on the rules of the game.

William Morris’s work loomed large behind this experiment. But unlike the founder of Arts & Crafts, Mari’s critique of alienation did not imply any fetish for rough-and-ready manual labor. For example, with the series of vases, Paros (1964), he took marble out of the hands of artisans and subjected it to industrial processes.

The technological turn had a potential to demystify things: it revealed how the almost exclusive use of artisan methods granted marble an exclusivist and sacred connotation, pushing up the costs of this material. With Paros, the forms and processes of production were rethought in relation with the physical-mechanical properties of marble, thus casting off the veil of its social status.

The result was a series of geometrical vases, cut with sharp contours, with drillings achieved with the most modern machinery. Now subjected to industrial techniques, marble left behind its divine aura and became a rather mundane material.

Design-It-Yourself

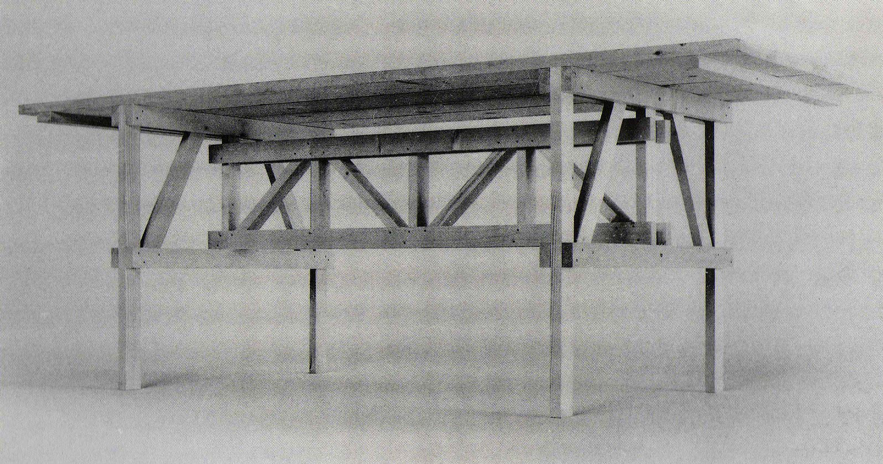

In 1974, Mari produced his most famous piece — or at least, the one that best summed up his ethos as a designer. Invited to put on an exhibition at the Galleria Milano, he designed a set of furniture with rough-cut slabs and nails, while also providing designs and instructions for their assembly.

All were invited to grapple with Autoprogettazione, as the show was called — literally, design-it-yourself — to build a table with their own hands in order to “better understand their underlying reason.”

Mari brought in low-price materials and a basic technical culture that he hoped all could master. He identified two main elements (the beam and the pilaster) joined them with nails and then strengthened them with a diagonal component — thus arriving at a structure based on a triangle. The furniture was produced not starting out from a design, but from the direct assembling of the wooden pieces through the chosen technique and instruments, without worrying too much about “finding the best solution.”

Mari’s “Autoprogettazione” asserted the right to experiment, restored a creative dignity to the process of construction, and tried to bring the body back into closer relationship with the material, exhorting participants to “think with their hands.”

The element of design would come only later, as the memory and footprint of an experiment that could be replicated only “unfaithfully.” But not everyone could do this. In the introduction to the instruction booklet, two categories are barred from making free use of his work: traders and industry. Autoprogettazione was a kind of anti-patent.

In 1975, the instructions for Autoprogettazione were republished together with a selection of texts responding to the initiative, including critical reviews and letters sent to Mari by those grappling with the effort of building for themselves. In his contribution, the historian Giulio Carlo Argan distinguished between Autoprogettazione and the “do-it-yourself” preached as a kind of hobby in US culture.

If this latter celebrated DIY for its own sake, Mari’s project has the sense of a challenge to be boldly confronted. Paraphrasing Mari, Argan said that everyone had to do their own design, to avoid being the object of someone else’s plans.

In his text for the catalogue, the designer railed against hobbyism, defining it a “degradation of culture, “making things by way of imitation, without any deep understanding of what you are making.” A form of escapism, remote from any real attempt to understand the materials and the rules of construction.

Recovering Skills?

But Mari was not naive, nor disingenuous. He made apparent the “uneconomic” aspect of his experiment to his public. “It would be mistaken,” he said, “to imagine a return to Arcadia, to a world in which each person does everything,” “industry is there” and “has to be occupied.”

Autoprogettazione was not a matter of each producing for themselves, but a gesture in critique of the capitalist world of objects and, at the same time, an exercise in bringing forgotten abilities back into view.

This aspect was explored in greater depth in an interview reproduced in the catalogue, in which the psychiatrist Elvio Fachinelli questioned Mari on the basis of his own personal reaction to the drawings. “Faced with your drawings,” commented Fachinelli, “I think that there ought to be a type of intermediate factory that supplies the already prepared and cut pieces. If there is not such a factory, we immediately think nothing can be done, that the project is unrealizable.”

With this observation, accepted and expanded upon by Mari, Fachinelli highlighted the ideological basis of the project’s shortcomings. The problem lay in the widespread sense that knowledge and savoir-faire are out of reach — a feeling that has its roots in the division of labor in society itself. Mari’s “do-it-yourself” aims less at testing technical skill than at recovering faculties for survival which had been forgotten.

Probably the prelude to Autoprogettazione was The Fable Game (1965), a book for children to take apart and put back together again. The Fable Game consisted of six sheets of card with animals and some elements of their habitat printed on either side. The sheets could be slotted into each other, building landscapes on which to play at inventing stories.

The game evokes Mari’s training in scenography, and is part of the debate on the “open text” pioneered by Umberto Eco. In 1962, Eco wrote for the publication accompanying the “Arte Programmata” show.

On that occasion, Mari exhibited a square screen illuminated from behind by a battery of intermittent lights giving rise to “an ever-different combination of colors.” The work embodied the marriage of seriality and chance promoted by the current, and broke with the traditional idea of the author, exercising a catalyzing, almost maieutic, function on perception.

This was the beginning of creative journey which endeavored to empower the user which would culminate in Autoprogettazione, passing by the The Fable Game.

Among Mari’s less well-known works is an atlas produced together with Francesco Leonetti, a writer, poet, and lecturer in aesthetics at Milan’s Brera academy of art. This was an unusual atlas, for its object was not geography but the fundaments of Marxism.

The Atlas According to Lenin (1976), is a book comprising of graphics and maps, with explanatory texts inserted in between. The historical map expounds the origin of capitalism, the social map the division of society into classes, the economic map the production of surplus-value, and the political one illustrates the proletariat’s seizure of power.

The atlas is a courageous attempt to explain the trickery of capitalism through all available languages: words and numbers, but also abstract and concrete forms, and colors. “Through collaboration and its results,” the authors write in the preface, “even contributing obviously diverse elements, specific ‘competencies’ become, in part, indistinguishable.”

Again here, Mari advanced a critique of the separations between disciplines. And in so doing, he offered a map that points to a new kind of knowledge.