Fifty Years Ago This Spring, Millions of Students Struck to End the War in Vietnam

In May 1970, 4 million students went on strike across the country, shutting down classes at hundreds of colleges, universities, and high schools and demanding an end to the Vietnam War. Fifty years later, their rebellion remains an inspiration, as radical student politics is back on the agenda.

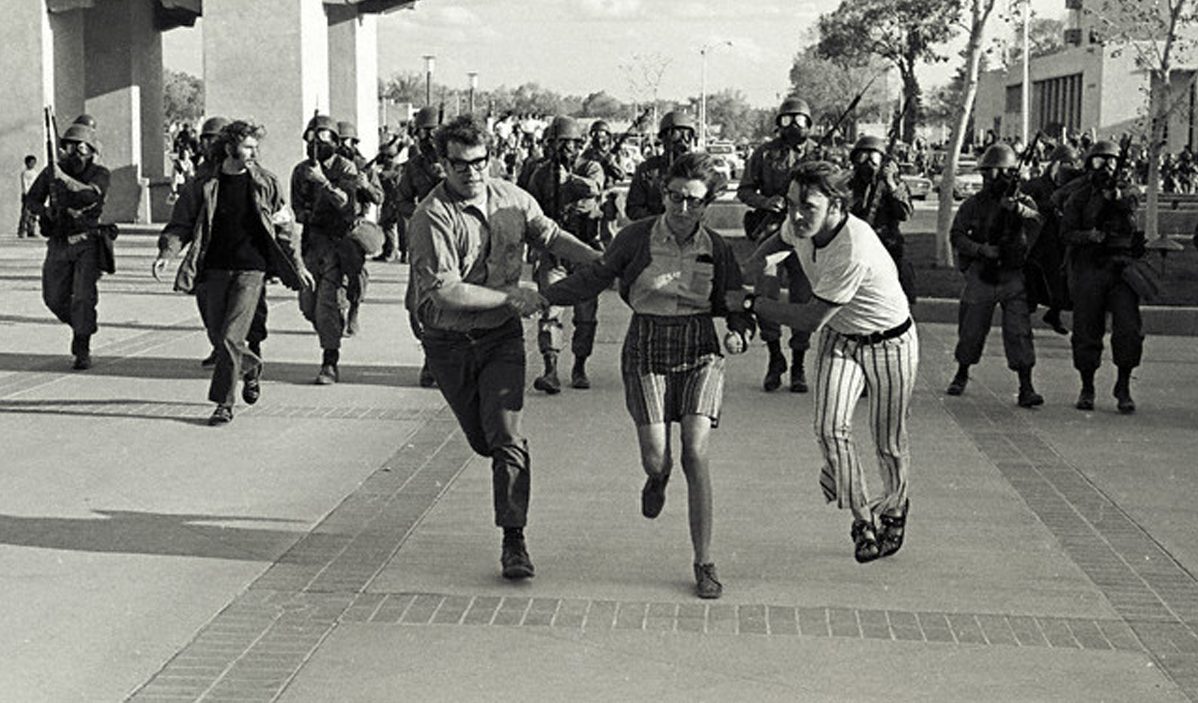

Following the May 4, 1970 shooting of students at Kent State University, students at UNM took over the student union building. Steven Clevenger / Corbis

President Richard Nixon prided himself on the accuracy of his political prognostication. He was never more prescient than in a remark made fifty years ago this month to his secretary, just before delivering a White House address that announced a US military invasion of Cambodia. “It’s possible,” Nixon told her, “that the campuses are really going to blow up after this speech.”

Blow up they did, as Nixon’s unexpected escalation of an already unpopular war in Vietnam triggered a chain of events culminating in the largest student strike in US history.

In May 1970, an estimated 4 million young people joined protests that shut down classes at seven hundred colleges, universities, and high schools around the country. Dozens were forced to remain closed for the rest of the spring semester.

Over the course of this unprecedented campus uprising, about two thousand students were arrested. After thirty buildings used by the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) were bombed or set on fire, heavily armed National Guards were deployed on twenty-one campuses in sixteen states.

On May 4, at Kent State University in Ohio, Guard members fresh from policing a Teamster wildcat strike shot and killed four students and wounded nine. Ten days later, Mississippi State Police opened fire on a women’s dormitory at Jackson State University, killing two more students.

America’s costly war in Southeast Asia had finally come home with stunning impact, creating what a later President’s Commission on Campus Unrest organized by Nixon (known as the Scranton Commission) called “an unparalleled crisis” in higher education.

The strike across campuses revealed the power of collective action. Born out of the shutdown, there was an explosion of activity by hundreds of thousands of students not previously engaged in anti-war activity, creating major political tremors across the country, including helping to curtail military intervention in Southeast Asia.

As Neil Sheehan notes in A Bright Shining Lie, his prize-winning Vietnam War history, the “bonfire of protest” ignited by Nixon’s “incursion” into Cambodia was so great that the White House “had no choice but to accelerate the withdrawal” of US troops from the region. Unfortunately, the halting pace of American disengagement continued for another five years, amid much further bloodshed among the Vietnamese (who suffered an estimated 3 million civilian and military deaths overall).

The Path to Protest

Some campus radicals started objecting to US policy in Vietnam during the first term of Nixon’s predecessor, Lyndon B. Johnson. Johnson campaigned in 1964 as the “peace candidate” in a presidential race against Senator Barry Goldwater, a rabidly right-wing Republican. But over the next two years, President Johnson began a massive military buildup to prevent his ally, the Republic of Vietnam, from being toppled in the southern part of the country by a communist-led nationalist insurgency.

Criticism of Johnson found its earliest and most polite expressions in “teach-ins” — on-campus debates and tutorials about Vietnam. But lots of talk soon turned to action. Hundreds and eventually thousands of local protests were organized — against military conscription and on-campus officer training, Pentagon-funded university research, and visiting corporate recruiters from arms makers like Dow Chemical Company.

An insurgent offensive in February 1968 and mounting US casualties (which eventually totaled sixty thousand) shattered any hope that Johnson had for military victory. Even after the president declined to run for reelection, anti-war protestors still descended on Washington, DC, in increasing numbers. In 1967, fifty thousand people marched on the Pentagon. Two years later, three hundred thousand gathered in protest near the White House.

Nixon replaced Johnson in January of 1969, after Democratic candidate Hubert Humphrey, Johnson’s vice president and loyal supporter of the war, was defeated in a three-day race. Nixon claimed to have a “secret plan” to bring peace to Vietnam and withdraw the five hundred thousand US troops still deployed there.

Once unveiled, Nixon’s plan turned out to be “Vietnamization” — shifting the combat burden to troops loyal to the US-backed government in Saigon, while conducting massive bombing of targets throughout Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. By April 30, 1970, the United States was sending ground troops into Cambodia as well.

Students at elite private institutions long associated with anti-war agitation were among the first to react. Protest strikes were quickly declared at Columbia, Princeton, Brandeis, and Yale, where many students had already voted to boycott class in support of the Black Panther Party, then on trial in New Haven.

Meanwhile, a Friday night riot outside student bars in downtown Kent, Ohio, was followed by the burning of a Kent State ROTC building over the weekend. Ohio governor James Rhodes ordered a thousand National Guard troops to occupy the campus and prevent rallies of any kind.

The Guard came geared with bayonets, tear gas grenades, shotguns, and M1s, a military rifle with long range and high velocity. Chasing a hostile but unarmed crowd of students across campus on May 4, one unit of weekend warriors suddenly wheeled and fired, killing four students.

Bringing the War Home

As historians Nancy Zaroulis and Gerald Sullivan described the scene in Who Spoke Up?:

It was a moment when the nation had been driven to use the weapons of war upon its youth, a moment when all the violence, hatred, and generational conflict of the previous decade was compressed into 13 seconds when the frightened, exhausted National Guardsmen, acting perhaps in panic or simple frustration, had turned on their taunters and taken their revenge.

In the aftermath of this fusillade, Guard officials orchestrated a cover-up exposed in The Killings at Kent State: How Murder Went Unpunished, by investigative reporter I. F. Stone. Even the FBI later found that the mass shooting was “unnecessary.”

The deaths of Jeffrey Miller, Allison Krause, Sandy Scheuer, and Bill Schroeder had a powerful impact on hundreds of thousands of students at Kent State and beyond. This time, the casualties of war were neither draftees from poor communities in the United States nor Vietnamese peasants — all of whom had been dying in much larger numbers for years. Nor were they African Americans, like the three student protestors fatally shot at South Carolina State University two years earlier, or the two murdered by state troopers at Jackson State University later that May.

The students in the kill zone at Kent State were mainly white and middle income, with draft deferments. Some had aggressively challenged the Guard’s presence, but many were simply bystanders, hanging around on the grass between classes. One target was an ROTC cadet who had just left a military science class before getting a bullet in the back. Another student, who survived, was paralyzed for life. (For first-person detail, see Kent State: Death and Dissent in the Long Sixties by Thomas M. Grace, a history major who was also wounded that day.)

In newspaper photos and TV coverage, the dazed Kent State survivors looked like college students everywhere. As one strike organizer at Middlebury College in Vermont recalls, those images “created a sense of vulnerability and crisis that many people had never experienced before.”

The resulting calls for campus shutdowns came from every direction. Students at MIT tracked which schools were on strike for a National Strike Information Center operating at Brandeis nearby. Soon the list was ten feet long. Despite its initial association with militant protest, most strike activity was peaceful and legal. It consisted of student assemblies taking strike votes, and then further mass meetings, speeches and lectures, vigils and memorial services, plus endless informal “rapping” about politics and the war.

A Radical Victory

The strike brought together a wide range of undergraduates, faculty members, and administrators — despite their past disagreements about on-campus protest activity. Thirty-four college and university presidents sent an open letter to Nixon calling for a speedy end to the war. The strike also united students from private and public colleges and local public high schools in working-class communities. On May 8, in Philadelphia, students from many different backgrounds and neighborhoods marched from five different directions to Independence Hall, where a crowd of one hundred thousand gathered outside. City high school attendance that day dropped to 10 percent, according to the Philadelphia Inquirer.

Hamilton College professor Maurice Isserman, coauthor of America Divided: The Civil War of the 1960s, believes that it was the more moderate students, those “who were anti-war but turned off by the rhetoric of the late ‘60s New Left” who “emerged as the leading force” in the aftermath of the upsurge. Indeed, many new recruits did gravitate toward anti-war lobbying, petitioning, and electoral campaigning rather than further direct action.

Yet the Scranton Commission viewed the politicization of higher education as a victory for student radicals. According to its later report, “students did not strike against their universities; they succeeded in making their universities strike against national policy.” To prevent that from happening again and get campus life back to normal, the commissioners agreed that “nothing is more important than an end to the war.”

In a Boston Globe interview on the thirtieth anniversary of this upsurge, Isserman argued that it was “the product of unique circumstances that, not surprisingly, provoked outrage from a generation of students already accustomed to protest and demonstration. It’s unlikely that we’ll ever see a movement quite like this again.”

That was certainly true for the next few years, as the Vietnam War wound down and Nixon, after winning reelection, conspired his way to impeachment, public disgrace, and forced resignation in 1974 over the Watergate scandal.

Yet over the past two decades, college and high-school students have walked out again, across the country, in highly visible and coordinated fashion. In March 2003, they poured out of 350 schools to protest the impending US invasion of Iraq. Fifteen years later, about 1 million students at 3,000 schools walked out to join a seventeen-minute vigil organized in response to the mass shooting at Parkland High School in Florida. And just last September, hundreds of thousands of students left school to join rallies and marches organized as part of a Global Climate Strike.

Universities and high schools are now experiencing a shutdown of their campuses, albeit of a very different kind. But when these institutions open back up, conditions will require a new set of political demands. A return to normal will not be good enough. When school is back in session, the history of a strike occurring after the shadow of death fell on campuses fifty years ago, thanks to Richard Nixon, may become more relevant to challenging “national policy” under the equally toxic Donald Trump.