The UAW Volkswagen Contract Is a Win for Unions in the South

After over 500 days of bargaining, the United Auto Workers have reached a first contract with Volkswagen in Chattanooga, Tennessee — a major breakthrough for unions in the South that lays the ground for further inroads at other employers across the region.

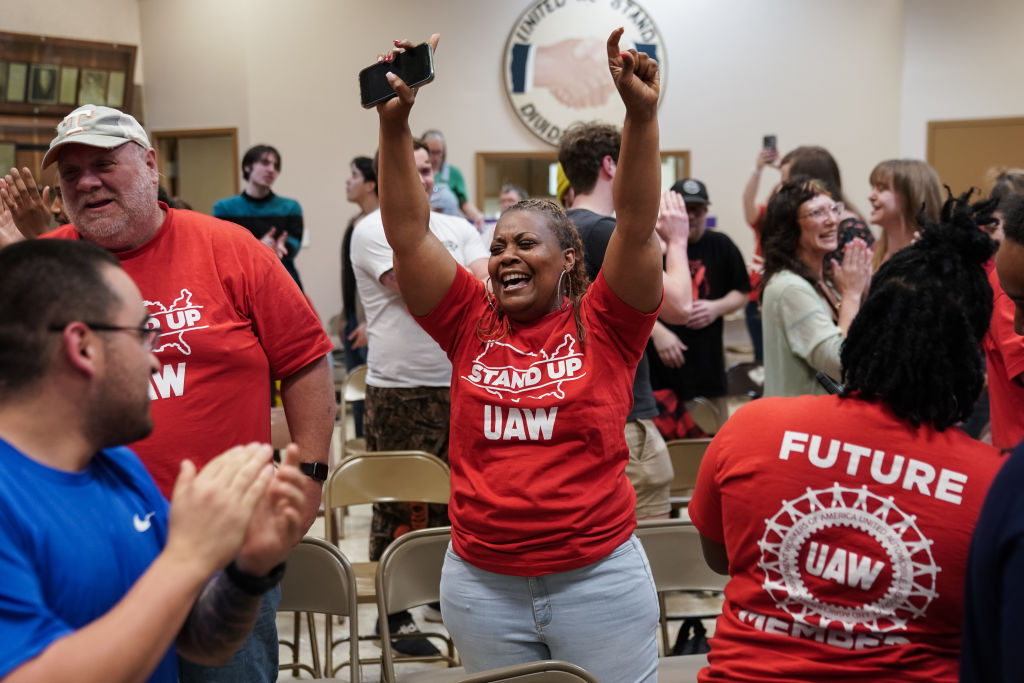

UAW workers in Chattanooga refused to let management slowly suffocate their union over the more than 500 days of bargaining their first contract — even when management suddenly declared that bargaining was over and tried to walk away from the table. (Elijah Nouvelage / Getty Images)

The United Auto Workers (UAW) have just marked one of the most important milestones in the union’s history: they have officially reached a tentative agreement on a first contract with Volkswagen in Chattanooga, Tennessee.

The agreement, reached on February 4, is the culmination of 502 days of bargaining and a successful strike authorization vote by a supermajority of workers in October of last year. It includes a 20 percent wage increase over four years, reduced health care costs, job security protections, the right to strike over health and safety grievances, the recognition of skilled trades, and many other protections and benefits. It will now proceed to a vote by the union’s members.

This marks the first time the union has successfully organized and bargained an agreement with a foreign-owned, nonunion auto company in the South and lays the ground for further inroads at other employers across the region. It is likely that the Volkswagen contract will result in yet another “UAW bump” for at least some autoworkers at nonunion auto companies whose employers have tried to blunt enthusiasm for unionizing, much like they did following the ratification of the historic UAW contracts at Ford, General Motors, and Stellantis in 2023.

This contract at Volkswagen not only is life-changing for the workers who won it and further expands the UAW’s density in its core industry. It also provides the threat of a good example. This agreement punctures the decades-old narrative that workers can’t organize the South. The victory in Tennessee provides a clear demonstration that workers can win when they combine strong organizing and disciplined bargaining and can build to a credible strike threat.

502 Days to a Deal

Workers at Volkswagen, the second most profitable auto company in the world, voted overwhelmingly to unionize in April 2024 and kicked off bargaining five months later on September 20 with a list of nearly seven hundred demands.

That sounds like a lot, but it appears less massive if you understand the nature of bargaining a first union contract. Unlike successor agreements, in which the union makes a narrow list of proposals to improve the terms and conditions of an already existing collective bargaining agreement, a first contract has to hammer out language on everything.

The list of items that need to be negotiated over in a first contract is extensive. For example, some of the items that Volkswagen workers had to negotiate include: which employees are covered by the agreement or excluded from it, the work done by the bargaining unit and limits on outside contractors, protections against being disciplined or terminated without just case, a grievance procedure for resolving contractual or disciplinary disputes, hourly wages, probationary periods for new hires, providing workers a cost-of-living adjustment so their wages maintain their purchasing power, profit sharing and other bonuses, holiday pay and vacation accrual, health care costs and coverage, sick leave, health and safety protections and procedures, and the recognition of skilled trades and hourly wage rates.

First contracts are like building an entire house from scratch, spanning from the foundation to the roof and furnishing all the rooms in between, whereas negotiating a successor agreement is more like choosing a room or two to make some upgrades in while fending off employer attempts to wreck the place.

Importantly, first contracts also provide employers with a second bite at the union-busting apple. There isn’t reliable data on the win rates for first contracts, but it wouldn’t be shocking if only around half of workers that win their union ever win a first contract. And when employers can’t break the union, they do the next best thing: stall negotiations out for as long as they can. After all, every day spent negotiating is a day without the added costs of raises, increased benefits, and more employee-friendly working conditions.

Volkswagen management put the “war of attrition” playbook into effect in Tennessee, endlessly dragging their feet in negotiations. According to a Bloomberg Law analysis of contracts ratified between 2020 and 2022, it took an average of five hundred days for unions to successfully negotiate and ratify a first contract, almost the exact amount of time it took workers to negotiate a first agreement with Volkswagen.

The difficulty in achieving a first contract proves yet again how Volkswagen, which markets itself as a high-road employer that values workers and unions, is no different than every other union-busting company that workers face off against.

In fact, last year, Volkswagen harassed, threatened, and illegally fired workers during an organizing drive at a parts depot in New Jersey. The company’s behavior was so egregious that the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) took the rare step of announcing the agency will be seeking an injunction ordering management to recognize the union and start bargaining.

The story of collective bargaining at Volkswagen is a familiar one. After workers won their union, management didn’t have a sudden change of heart. Instead, the company followed the standard anti-union strategy of attrition, betting that by delaying bargaining they could sap worker momentum from their organizing victory and weaken the union.

The workers in Chattanooga refused to let management slowly suffocate their union — even when management suddenly declared that bargaining was over and tried to walk away from the table. Late last year, at the same time the NLRB was announcing their plan to file for an injunction in New Jersey, Volkswagen management in Chattanooga publicly issued what they described as their “last, best and final offer” to the union in a desperate attempt to scare the workers into taking a deal that fell far short of what the union was fighting for.

LBFO vs. FAFO

Last, best, and final offers (LBFOs) are common in union negotiations. As their name suggests, LBFOs are a package of proposals presented by management as the take-it-or-leave it conclusion to bargaining. Once management presents the union with an LBFO, the employer has three options: declare “impasse” and force their final offer on to the workers, lock out the workers and bring in scabs to perform their jobs in an attempt to coerce the union into accepting the deal, or continue bargaining.

Impasse is the point in negotiations at which the parties are deadlocked — neither side is willing to make further concessions, and continued bargaining would be futile. Once a contract has expired and lawful impasse has been reached, the employer may unilaterally implement some or all of its last, best, and final proposals. But an impasse is unlawful if key legal conditions are not met: the union has outstanding requests for relevant information, the employer is insisting on a permissive rather than legally mandatory subject of bargaining, or the employer has committed an unfair labor practice (ULP) that taints negotiations.

In these circumstances, unilateral implementation is illegal, no matter how stalled bargaining may be. Skilled negotiators can exploit these constraints — through detailed information requests and tactics that expose employer ULPs — to make lawful imposition exceedingly difficult. And even when an employer manages to lawfully declare impasse, the union can still make counteroffers, and the employer remains legally obligated to continue bargaining.

A lockout occurs when an employer bars employees from working and temporarily replaces them with scabs in an effort to coerce the union into accepting its terms. Unlike striking workers, employees who are locked out can typically qualify for unemployment benefits in most states. And if the employer has committed unfair labor practices that impact bargaining, the NLRB may declare the lockout unlawful, order workers reinstated, and require the employer to pay back wages. These legal risks can make lockouts a high-stakes tactic for employers — and in some cases, a more advantageous scenario for workers than a strike.

At Volkswagen, the UAW had multiple, strong ULP charges against the company. These charges made both an impasse and lockout strategy unlawful. And soon after the company publicly announced their “last, best, final offer,” the union provided the company with a comprehensive counterproposal, demonstrating that there was ample room to continue bargaining.

The workers at Volkswagen chose to call management’s bluff and took the next big step: a supermajority of workers voted to authorize their bargaining committee to call a strike if needed. The strike vote sent shock waves through Volkswagen management, who were banking on Southern workers being docile and susceptible to the company’s threats. Unable to lawfully declare impasse or lock out their employees, management was forced to continue bargaining, but it also now was staring down a strike threat.

The results speak for themselves: the tentative agreement has significant improvements from the company’s LBFO. The union won millions of additional dollars in reductions to health care costs, significant improvements to job security language around plant closures and sale of operations, the right to strike over health and safety, and formal contractual commitments for vehicles — and the jobs they bring — to be produced at the Chattanooga plant over the next decade. And while many Americans are staring down health care inflation in the coming years, the workers at Volkswagen are contractually guaranteed no health care cost increases over the life of the four-year agreement.

I’ve overseen, supported, or directly bargained many contracts over my career, including dozens of first contracts, and LBFOs are common scare tactics used by management to try and bully workers into accepting a deal on the employer’s terms. I’ve also seen how collective action and savvy negotiating can force employers who issue an LBFO only to come back with another offer. And then another. And then another. In many negotiations, management’s “latest” LBFO became a running joke on the union side of the table.

That’s what happened in Tennessee. Volkswagen management gave an LBFO and UAW members responded with an acronym of their own: FAFO. Thanks to their credible strike threat, workers in Chattanooga made one of the powerful corporations in the world capitulate to their demands and have now won a life-changing, trailblazing first collective bargaining agreement. After over five hundred days of bargaining, the United Auto Workers have reached a first contract with Volkswagen in Chattanooga, Tennessee — a major breakthrough for union organizing in the South that lays the ground for further inroads at other employers across the region. Hopefully, more Southern autoworkers will be following in their footsteps soon.