Mothers Are on the Front Lines of the Nordic Care Crisis

In Sweden today, maternal activism is uniting around a politics of collective care, turning private burdens into claims about public obligation and democratic rights.

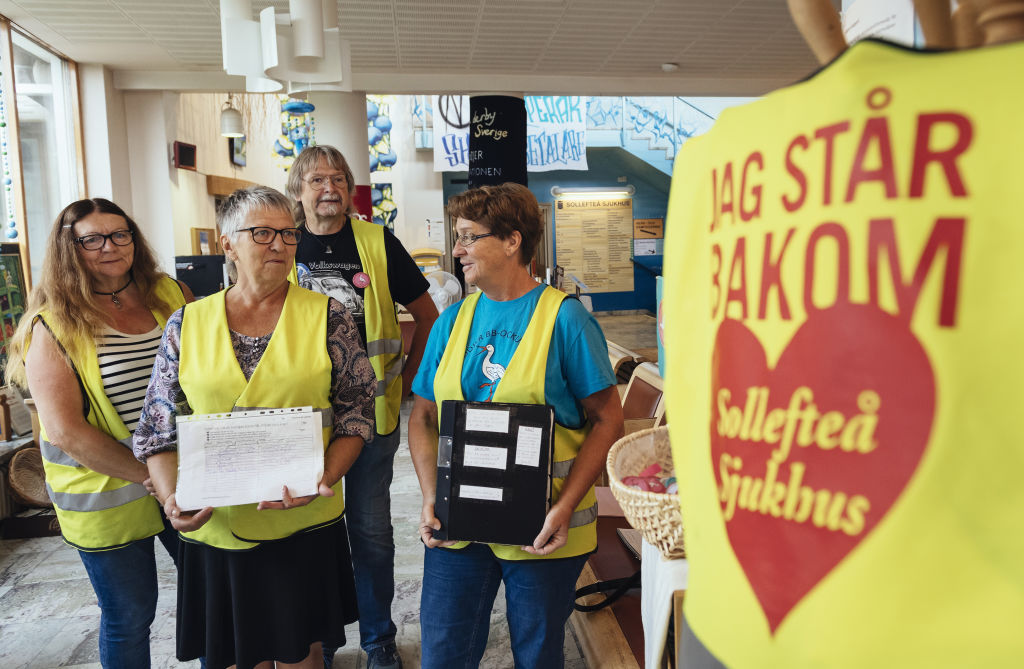

Sweden’s motherhood movements confirm that the care crisis is not simply a technical policy problem but a crisis of social provision under capitalism. (Mikael Sjoberg / Bloomberg via Getty Images)

For decades the Nordic welfare states have been held up as global exemplars of gender equality and expansive public care systems. Yet beneath this image of egalitarian modernity, cracks have begun to widen. Across Europe and North America, scholars increasingly speak of a mounting care crisis — a systemic imbalance in which society’s care needs outstrip the institutional capacities meant to meet them. The Nordic countries, once shielded by generous welfare infrastructures, are no exception.

In Sweden, this crisis is not a sudden rupture but a slow political shift: welfare retrenchment, austerity-driven reforms, marketization, and an intensifying moralization of family life. As public systems fail to keep pace with rising needs, more and more responsibility for the reproduction of daily life is quietly pushed back onto households. This process — what feminist scholars call refamiliarization — has become a defining feature of contemporary social policy. And, as always, the costs fall unevenly: on mothers, on low-income families, on people with disabilities, and on those navigating the intersecting inequalities that make care both more necessary and harder to access. But something else is happening too. Across Sweden, groups of mothers are refusing to silently absorb the state’s abdication. Instead, they are organizing.

When the Welfare State Retreats, Mothers Step Forward

In recent years, Sweden has seen the rise of several mother-led movements demanding public accountability for children’s right to care, safety, and recognition. These movements differ in constituency and political issue, yet they share a common insight: care is political, and its organization reflects deeper struggles over responsibility, resources, and democracy. For example, Funkismammor (Special needs moms), a loose network of mothers of children with disabilities, fights the chronic underfunding of support services and the discrimination woven into everyday encounters with welfare agencies.

For several years, mothers involved in the maternity ward strike in Sollefteå — a small town in northern Sweden — have built powerful grassroots networks to defend their basic right to safe and accessible birth care. In a community heavily impacted by welfare cutbacks and the closure of essential services, these women mobilize to protest the shutdown of their local maternity ward and the long, often dangerous travel distances now required for childbirth.

These are not traditional social movements, nor are they simply interest groups advocating for “their own.” They represent something more profound: grassroots responses to the hollowing out of public care, and collective refusals to accept the intensified burdens placed on women within the private sphere.

The New Politics of Care

Feminist social reproduction theory helps explain why these mobilizations have emerged now. In capitalist societies, the unpaid labor that sustains life — raising children, tending to the ill, maintaining households — remains structurally essential yet systematically undervalued. Nordic welfare states once mitigated this contradiction by socializing parts of reproductive labor — childcare, eldercare, and disability services. But as these services contract, or become more conditional, the old tensions return with renewed force.

Into this vacuum, a new moral discourse has emerged: one that demands ever more intensive, individualized, and “responsible” parenting. Parents — mostly mothers — are expected to fill the gaps left by failing systems and blamed when those systems’ failures manifest in social problems: mental health crises, school absenteeism, youth violence. This moralization is not merely cultural — it is political. As care is pushed back into the family, the boundary between public responsibility and private obligation becomes a site of conflict. Nancy Fraser describes these conflicts as boundary struggles, and Swedish mothers are increasingly finding themselves at their center.

Mother-led movements have long been politically ambivalent. Historically, appeals to motherhood have been used to mobilize both progressive and reactionary causes — invoking images of the “good mother,” the “moral protector,” or the “guardian of the nation.” Yet in contemporary Sweden, maternal activism is taking a distinctly structural turn. These groups are not rallying around conservative ideals of family or gender. They are mobilizing around the state’s failure to guarantee collective care. Their framing practices recode private experiences into public claims. A lack of gender-affirming care becomes a question of democratic rights. The bureaucratic maze faced by parents of children with disabilities becomes evidence of institutional discrimination. In doing so, these mothers challenge dominant narratives that individualize social problems and push responsibility downward. They expose the political nature of care — and the political consequences of its neglect.

Crucially, these movements do not only issue demands — they build things. In the absence of reliable public care, mothers create bottom-up care infrastructures: peer support groups, knowledge sharing networks, informal counseling, and advocacy collectives. This infrastructure serves to provide a ground for survival strategies for families navigating fragmented welfare systems. But they also function as spaces of politicization, where women articulate shared grievances and formulate collective demands. This dual role — providing care while contesting the conditions that make such care necessary — offers a powerful model for understanding how social reproduction becomes a site of struggle.

The Swedish state’s responses to these mobilizations vary widely. In some cases, authorities offer recognition or limited cooperation; in others, they deflect responsibility, bureaucratize demands, or pathologize parents’ concerns. These interactions reveal boundary struggles in real time, as the state negotiates, evades, or redefines demands that challenge the shifting line between public obligation and private burden. Studying these interactions illuminates a larger political question: When mothers refuse to quietly pick up the pieces of a shrinking welfare state, how does the state react?

The Future of the Swedish Welfare State Runs Through the Politics of Care

Sweden’s motherhood movements are telling us something essential: the care crisis is not just a policy failure — it is part of a crisis of capitalism. It reveals whose needs are recognized, whose labor is valued, and whose voices shape the future of the welfare state.

By foregrounding care as a political issue rather than a private duty, these mothers expose the ideological work required to sustain a social order in which the state retreats while families are expected to absorb the consequences. Their mobilizations remind us that care is not simply a sentimental value; it is the foundation of social life. And when the institutions meant to guarantee that foundation begin to crumble, it is often mothers who are first to notice — and first to resist.

The question now is whether Swedish society will listen.