An American Communist Like No Other

- Julia Damphouse

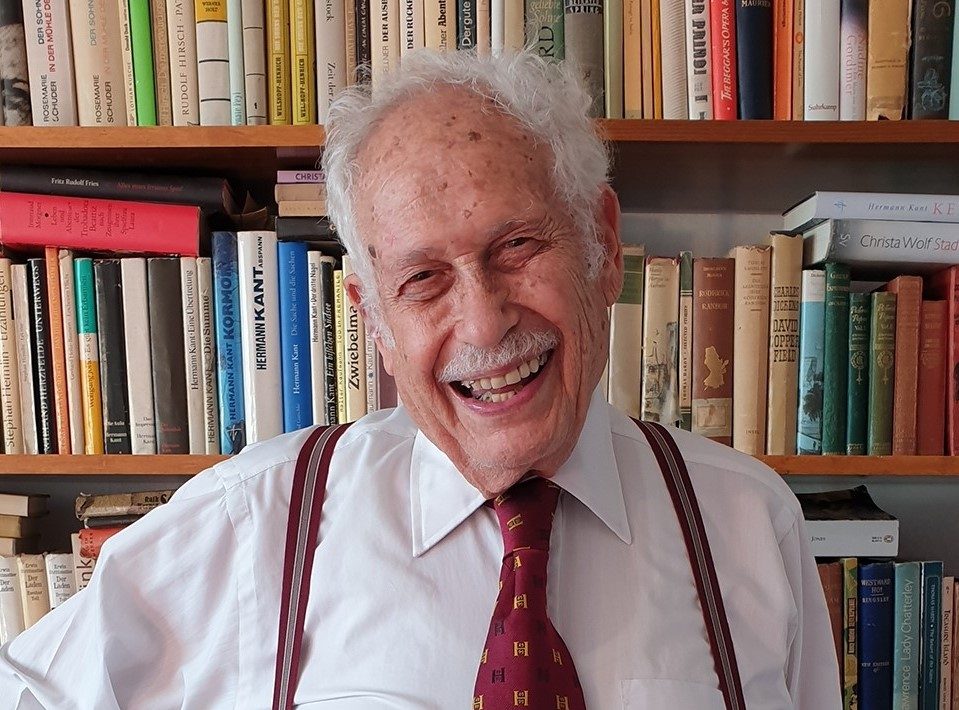

Victor Grossman died in Berlin, aged 97, last Wednesday. An American communist, his life was forever shaped by his defection to the Eastern Bloc at the height of the Cold War.

Viktor Grossman's extraordinary life pivoted on a decisive choice he made in 1952: to defect to the Eastern Bloc rather than allow the US Army to jail him.(Facebook)

It is no exaggeration to call Victor Grossman a witness to the last century. Born in New York City on March 11, 1928, the journalist spent most of his life first in East Germany (GDR) and then, after 1990, in the reunified Germany, yet he always remained an American. His life story, vividly recounted in his autobiography Crossing the River, is the exemplary journey of a communist between worlds who remained unwaveringly true to his convictions. The book is also testimony to the fact that the GDR — despite all its serious failings, both avoidable and perhaps unavoidable — sought a legitimate and alternative path to the course of German history up to that point.

Stephen Wechsler — as Victor was originally named — grew up in New York as the son of an art dealer and a librarian. His family had escaped the antisemitic pogroms of tsarist Russia before 1900. His childhood memories were linked to the sweeping misery of the Great Depression, which forced the family to move several times. The young Wechsler’s left-wing orientation was thus in a sense predetermined.

While still in high school, he joined the Young Communist League in 1942. This was not surprising in New York at the time: most of his classmates leaned toward either the Communist or Socialist party. There were also some Trotskyists. An early role model was Congressman Vito Marcantonio, who was elected to the House of Representatives several times for the American Labor Party (which only ran in New York state).

In 1945, with the Allied victory over Adolf Hitler no longer in doubt, Wechsler joined the Communist Party USA (CPUSA), convinced he was on the right side of history. He also wanted to help eliminate the stark differences in American society, its racism and bigotry, in favor of a better model. He saw the alternative — and he was not alone in this — in the idealized Soviet Union, which he knew only from the propaganda writings circulating in America and from the no less crude anti-communist tracts of its enemies.

In the year he joined the party, he began studying economics at Harvard University, graduating with honors in 1949. He would have liked to continue with doctoral studies, but the CPUSA expected him to work in industry, as there were too few industrial workers among the party members. A party instructor gave him and other comrades the following advice: “You have learned a lot and know the theory. But you shouldn’t talk to the workers like that. Talk to the workers in a way that they can understand you. Speak their language.“ He later often had to think about this in the GDR.

Ambassador for Another America

After a period as an unskilled industrial worker in Buffalo, Wechsler was drafted into the US Army in 1950 and stationed in Bavaria. During an official interrogation, he concealed his party membership and was summoned before a military court for making false statements. In the hysterically anti-communist zeitgeist of the McCarthy era, he faced several years in prison. Seeking advice, he turned to the KPD office in Nuremberg but was sent away because they thought he was a provocateur. So he made a difficult decision, described for the first time in his 1985 autobiographical book Der Weg zur Grenze.

On August 12, 1952, the day he described as the most decisive of his life, he deserted. He swam across the Danube near Linz into the Soviet-occupied zone of Austria and reported to a Soviet military post. After two weeks of interrogation, he was taken via Czechoslovakia to the GDR, initially to Potsdam. After two more months in Soviet custody, he was sent to an open camp in Bautzen, a collection point for Western deserters, mainly from the Federal Republic of Germany but also from France and the English-speaking countries. From then on, he called himself Victor Grossman to protect his relatives in the United States. Until 1954, he worked at a train car building firm and took a special course to learn not only the German language but also the profession of turner. He was appointed cultural director of a club for other foreigners there.

From 1954 to 1958, he studied journalism at Karl Marx University in Leipzig. As a member of the CPUSA, he was a guest in the SED (Socialist Unity Party of the GDR) party group. There he also found his life partner. From 1955 until her death, Victor Grossman was married to librarian Renate Kschiner. The marriage produced two sons, Thomas and Timothy. He was and remained loyal to the GDR and the SED, but he occasionally caused offense when contradicting distorted opinions about life under capitalism.

After successfully completing his studies, he initially worked as an editor at Seven Seas publishers in Berlin. The publishing house was run by Gertrude Gelbin, novelist Stefan Heym’s wife, and published English-language books by communist authors from the United States, as well as numerous writings by members of the liberation movements in Asia and Africa associated with the Soviet Union and the GDR. Although the books hardly reached the Western book market, they did reach a growing audience in South Asia, particularly in India.

From 1959 to 1963, Victor Grossman worked for the German Democratic Report, an English-language digest of the GDR press, which was headed by the English journalist John Peet. He then spent two years as North America editor at Radio Berlin International, the foreign service of GDR radio. For him, the subsequent three years as director of the Paul Robeson Archive at the Academy of Arts of the GDR was more than just a professional assignment. From 1968 onwards, he worked as a freelance journalist, publishing commentaries in the daily press as well as in the foreign-policy magazine Horizont and the cultural policy monthly Das Magazin, which was edited by his close friend Hilde Eisler. His friendship with her and her husband, Gerhart, who died in 1968, dated back to their time in exile in the United States.

Victor played an important role in disseminating progressive American culture in the GDR. After the 11th Central Committee Plenum of the SED in December 1965, almost the entire GDR film production of that year was banned from distribution along with important literary texts. This was accompanied by an ideological campaign against Anglo-American culture. Bands (referred to as “dance bands”) who refused to remove English-language songs from their repertoires were banned from performing or forced to disband.

During these dark years of GDR cultural policy, which lasted until 1971, Grossman managed to release a few records featuring artists from the “other America” — the only way they could be accepted by the GDR — accompanied by introductory texts or liner notes. These included LPs by Bob Dylan, Pete Seeger, and Joan Baez — even though Seeger had left the CPUSA in 1949 after Joseph Stalin’s break with Tito and Baez had denounced the violent suppression of the Prague Spring in 1968. Victor wrote most of his texts in German, which also made him a mediator between East and West. His finest book, in my opinion, remains Rebel Girls: 34 American Women in Portrait (published in German, not English) — from Anne Hutchinson, the combative seventeenth-century theologian, to Jane Fonda. He gave it to me with the dedication “Pasaremos!” and accepted my criticism when I pointed out the absence of Emma Goldman from the book.

Unfillable Shoes

During the years of decline and disintegration of the GDR, Grossman remained politically engaged. He stood by the GDR, despite doubts about it, and he took it as a personal defeat when his adopted homeland was abandoned by many of its own citizens. He was nonetheless pleased for them, in terms of their newly won civil liberties. This also benefited him when, in 1994, he was allowed to travel to the United States for the first time since his escape, having always remained a US citizen. After an official hearing, he was discharged from the US Army.

He transferred his CPUSA membership to the Party of Democratic Socialism and later to Die Linke. He gave lectures in party groups and various antifascist organizations, including repeatedly in the Association of Fighters and Friends of the Spanish Republic, published in left-wing outlets, and wrote a mailing list, the Berlin Bulletin, in which he presented and analyzed European politics in an easily acceptable format for a global audience.

Victor lived an exemplary life. He was one of the courageous people — Communists, fellow travelers, and Trotskyists — who stood up to the inhuman mob that tried to lynch Paul Robeson and Pete Seeger in Peekskill, New York, on August 27 and September 4, 1949. He was shocked to learn that former CPUSA general secretary Gus Hall had used large sums of party funds for purely private purposes. Yet Victor’s commitment was unwavering: he maintained that communism was more than the abuse of power by its functionaries. With a clear standpoint, he was the most polite and tolerant discussion partner imaginable, even when we had very different positions.

On December 17, 2025, Victor Grossman died in Berlin at the age of 97. “A post is vacant,” to quote Heinrich Heine. “One falls, another takes his place.” But this position, which Victor had taken and held, remains vacant. For his unique experience, gained from different worlds, which he was always ready to critically examine, is and remains irreplaceable, indeed unrepeatable. Let us be grateful for what he has given us.