A Sober Look at Amazon’s Automation Drive

As Amazon rolls out its millionth robot on the warehouse floor, it is important to recognize that the company is not any closer to ridding itself of the burden of human labor. Amazon can still be unionized.

There is no employment apocalypse coming at Amazon. The near future of “efficiency gains” will be much like the recent past: increased surveillance, discipline, and gigification. (Miguel J. Rodriguez Carrillo / Bloomberg via Getty Images)

Earlier this year, Amazon announced the deployment of its one-millionth robot. Although the company stresses in all of its communications that robots “work alongside our employees,” augmenting and making human labor easier rather than displacing it (they even call their robots “cobots”), the business press clearly saw the implications. “Amazon Is on the Cusp of Using More Robots Than Humans in Its Warehouses,” claimed the Wall Street Journal.

Combined with a more recent New York Times revelation of company plans to eliminate 600,000 jobs by 2033, the robotics news out of Amazon has many worried about an imminent employment apocalypse at the company. Amazon CEO Andy Jassy has bragged about how robots are “improving cost efficiencies,” and one has to exercise willful disbelief to think he’s not talking about labor costs.

With all the gaslighting around the question of technological displacement, it’s not uncommon to hear people express wild fears about a jobless future thanks to the mass deployment of artificial intelligence systems and robots. Indeed, I would argue that the gaslighting and the employment apocalypse fantasies are mutually reinforcing: since Amazon and others won’t say the obvious truth, fears for the worst can proliferate; and as more and more people envision mass AI job displacement, realistic assessments of the meaning of AI and robotics developments become less likely.

Amazon is undoubtedly aiming to displace labor with its robotics deployments. But what does this mean for its workers? Which kinds of workers are most likely to be affected, and which are, for the moment, fairly immune to its automation efforts? What is a likely future for Amazon’s employment numbers given existing trends and the predicted rollout of new technologies? Tentatively answering these questions might at least put us on the path to some sobriety about Amazon’s robotic future.

Kivas and Robotic Arms

In much of the video coverage of Amazon’s robots, you tend to see stock footage of Digit, the humanoid robot that Amazon has partnered with Agility Robotics to develop. But when Amazon talks about its robots, it does not mean humanoid service robots. It mainly means its Kivas: the Roomba-like robots that move things around its warehouse floors. The most widely deployed Kiva is the Hercules, which carries giant stacks of inventory around fulfillment center floors to inventory stowers and order pickers. In Amazon Unbound, Brad Stone estimates that the average pick rate in a fulfillment center jumped from 100 items an hour to 300–400 after the introduction of Kiva technology.

The basic Kiva model has also been outfitted with a conveyor tray for Amazon’s Pegasus robot, which has been used as an alternative to conveyor belt sorting in some of its sortation centers. Both Hercules and Pegasus operate in fenced-off areas of warehouses, safely segregated from humans (whom they could seriously injure or kill, being 250 pounds each with the capacity to carry up to 1,250 pounds more). But Amazon also now has an autonomously guided Kiva called the Proteus, which moves around among human beings, carrying carts to and fro.

Amazon’s recent press release simply mentioned its one millionth robot, but another one just two years ago names 750,000 mobile robots. Given that any single Amazon Robotics sortable (ARS) fulfillment center could have well over 5,000 mobile units, it’s safe to say that the overwhelming majority of its one million deployed robots are Kivas. The rest are robotic arms, like Robin, Sparrow (used in its Sequoia automated stowing/picking system) and Vulcan, packaging or sort machines (many third-party), combined systems, or novelties.

The Kiva investment has been the one clear winner for Amazon, and it’s why the lion’s share of its one million robots are Kivas. As I demonstrate here, the primary site of Kiva deployment, which just so happens also to be the largest employment cluster in Amazon’s distribution network, is the ARS fulfillment center, and there the company has seen a 25 percent reduction in the Amazon workforce over just the last two years, accounting for productivity growth.

The next big thing in Amazon robotics in terms of use at scale will likely be one of the robotic arms systems, or at least that’s what Amazon is hoping. Both Sequoia and Vulcan would automate about three-fourths of stowing/picking, the most plentiful, baseline fulfillment center work, but to my knowledge, Sequoia has only been rolled out facility-wide in Shreveport, Louisiana, and Vulcan is only being piloted in Spokane, Washington. If I had to guess, Amazon will move more quickly with Vulcan, as it better integrates with their existing mesh-band pods, but even this will be a slow process. Amazon has the ability to devote a tremendous amount of capital expenditure to its robotics development. The thing holding back this investment is the simple fact that it’s ultimately pretty cheap to pay human stowers/pickers and quite expensive by comparison to develop and manufacture sophisticated robotics systems.

In addition, the robotic arms essentially replace human labor on a one-to-one basis: one robotic arm for one set of human hands. It’s certainly worth it from their perspective because you can run a robotic arm day and night, and it doesn’t need health care. But the Kivas, by contrast, completely reorganized inventory management at Amazon, allowing for much greater efficiency gains than any robotic arm program could hope to accomplish. So while it does seem like Amazon is ready to start really using robotic stowing/picking technology at scale (it already uses larger robotic arms for moving pallets and sorting packages), there are inherent limits to its efficiency gains at current prices.

Last Mile

Again, the Kivas are the big winner, and they account for most of Amazon’s robots. The robotic arm program will probably figure out something to work at scale, but it’s still in its infancy and probably won’t achieve the productivity gains of the Kiva rollout.

What Amazon and many other companies would like us to believe is that they’re on the cusp of similar gains in last-mile technologies, but here I think a very healthy dose of skepticism is warranted. Certainly the incentive to automate the last mile is there: the last mile, i.e., the journey of a package from the delivery station to your home, is the most expensive leg of any package’s journey, often accounting for more than 50 percent of shipping costs. It’s traditionally quite labor intensive, as there’s really not much of a substitute for paying someone to drive around town dropping off packages, and for these reasons, the Teamsters and others have focused their Amazon organizing efforts to date on delivery stations.

Amazon has tried out sidewalk roamers but shuttered that program in 2022. Now it has drone delivery pilot programs in a few places, where large and very loud drones drop packages from more than ten feet in the air. They don’t want their drones to hit people or even be low enough that an enraged Ron Swanson type could hit it out of the air with a baseball bat, so for the moment packages have to be dropped from a rather precipitous height, after which they typically take a few healthy bounces (and might end up in your pool). Recently Amazon has announced that it’s seeing if it can get humanoid robots to jump off the back of Rivians and deliver packages.

These are great stories for investors, but it seems highly unlikely that any of these last-mile automation efforts are going to amount to a great deal. Robots work well at scale in highly controlled environments. The Hercules robots operate on flat surfaces with QR codes every few feet, and they still malfunction enough that Amazon needs amnesty workers (technical “first responders” on AR floors) and reliability maintenance engineers (RMEs) all over their ARS facilities.

Think now of everything involved in taking a package from your car or van, maneuvering around trees near sidewalks, fences, gates, stoops, steps, and so on, and then dropping a package in front of a door or in a lobby and taking a picture of it. A human being can do all of this, with a great amount of variability with each delivery, fairly easily. Near-infinite variability for robotics, by contrast, is a hell scenario. Unless you have individual human remote pilots for each of the robots, which sort of defeats the purpose of rolling out robots in the first place, it’s really difficult to replicate a person with a truck.

I’m a little higher on the possibilities for drone delivery than some, though as a tiny addition to last-mile options rather than as a core last-mile technology. Willing and able to obliterate low airspace rights, Amazon and other drone delivery programs have theoretically created an obstruction-free space for operation. It’s not going to work everywhere, but for suburban areas of the right density, it could become a regular feature, i.e., a huge annoyance that city councilors will hear a great deal about. But even Amazon’s own stated goals for the program are less than 6 percent of deliveries by 2030 — a goal that they are most certainly not going to meet.

Amazon knows all this, and it’s why its “genius” technological solution to last-mile delivery is simply intense surveillance and aggressive subcontracting of its delivery workforce. This has undoubtedly been a “win” for Amazon, but it’s one that relies not upon the brilliance of its robotics wing but rather on the typical workplace fissuring and labor discipline tactics that all big corporations have used in the last fifty or so years.

Amazon in 2030

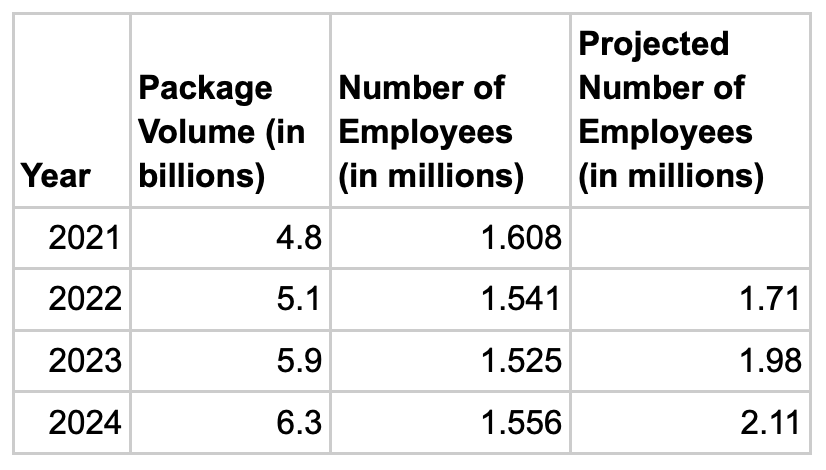

It should be kept in mind that Amazon has been displacing work for some time, if you account for productivity gains. In 2020, Amazon Logistics’ package volume jumped to 4.8 billion from 2 billion in 2019, and in 2024 it was at 6.3 billion. In that same time, Amazon’s total number of employees has slightly dipped — not much of a change by the numbers, but a clear displacement given productivity increases. The year 2021 was when that the robot rollout really increased in speed.

If the three-year trend here continues, Amazon would be delivering 10.8 billion packages in 2030 with only 1.45 million employees. That package volume number seems near impossible, unless the e-commerce share of retail (hovering around 16 percent since the pandemic) really starts to grow. Amazon has been eating the other parcel carriers’ lunches, and at some point, the steady package volume growth since the pandemic will level off, at which point we’d potentially see more dramatic job shrinkage — unless the productivity gains slow too.

A more reasonable 2030 scenario would be 8 billion packages (a remarkable milestone in itself). Factoring in this slowing growth to the employment trend in the last three years would mean 1.08 million employees in 2030. This would be the worst-case scenario for employment, but this too seems highly unlikely. Again, the primary robotics win in the past few years has been the mass deployment of mobile units, but this is now mostly accomplished, as the predominance of Amazon sortable FCs are outfitted with Kivas. Like the preposterous package volume gains during the pandemic, the huge worker displacement rate at sortable FCs in the past few years cannot be sustained.

From here on out, Amazon will mostly be relying on its Sequoia/Vulcan rollout and other upgrades of its most recent generation of fulfillment centers for continuing worker displacement. Referencing the Sequoia rollout at SHV1 in Shreveport, Louisiana, one of Amazon’s most recent generation of FCs, Brian Nowak from Morgan Stanley has suggested that “the base case robotics penetration could reach 30% by 2030.” An average ARS fulfillment center of its size would typically be employing 3,069 workers, and according to that recent New York Times article, fulfillment centers outfitted with SHV1 technology only need about 70 percent of the workers of other ARS facilities (~2,148 workers).

As there are roughly 391,000 sortable fulfillment center workers in the United States, a 30 percent reduction in the workforces of 30 percent of Amazon’s Sortable Fulfillment Centers would involve 35,190 fewer sortable FC workers — a 9 percent decrease. I don’t have great numbers on Amazon’s international workforce, but running with the idea that 70 percent of Amazon workers are in the United States, a similar decrease in international FC workers would involve 15,081 sortable FC workers, meaning 50,271 sortable FC workers would be displaced if Nowak’s prediction comes to pass. Factor in some continuing displacement from the remaining Kiva rollout, and that’s maybe 70,000 fewer sortable FC workers in the world.

However, if we went by the trend of the last two years (2022–24), we’d also have to include increases in average employment numbers at other kinds of Amazon facilities. In the same period that average sortable FC employment in the US dipped from 3,165 to 2,918, average employment at Amazon inbound cross-docks (their first-mile import receiving facilities) jumped from 2,394 to 2,518, and at sortation centers (their middle-mile facilities sorting packages by zip code) from 825 to 887. In fact, projecting this employment trend at all Amazon facility types in the United States out to 2030 would mean a reduction in the total sortable and nonsort FC workforce of 112,406, but an overall increase of 33,389 workers.

Of course, it’s possible that Amazon figures out automation solutions for these other kinds of facilities as well. It has tried Kivas at delivery dtations with no real success, but the auto divert to aisle (ADTA) system has worked well there. Its inbound cross-docks have many manual sorters still, but it is experimenting with different automated sort systems there too. It has tried and then rolled back Amazon Robotics automation at its nonsort fulfillment centers for bulkier items, but average annual employment has nonetheless dipped at those facilities in the last two years as well.

At a certain point, the guesswork becomes somewhat ridiculous, but given all of this, I’d say a reasonable scenario for Amazon in 2030 is a package volume of 8 billion with a global workforce about what it is now, i.e., between 1.5 and 1.6 million, but perhaps dipping to 1.35–1.4 million if the next-generation fulfillment center rollout really picks up steam. That involves a great amount of displacement, but it is no employment apocalypse. And this number of course does not include the hundreds of thousands of subcontracted Amazon delivery drivers, the number of whom is likely to grow with package volume, given the lack of feasibility in last-mile automation.

It’s important to note that these are estimates based on possible robotics upgrades. At some facilities, Amazon is replacing part-timers with Amazon Flex (i.e., gig) workers; at others, everyone outside of management is working Flex. If this model is ported to other facilities, Amazon’s employee count could crater for non-robotics-related reasons.

More of the Same

In short, we’re likely to see more of the same from Amazon: intense labor surveillance, discipline, and subcontracting/gigification combined with displacement of labor through robotics improvements that are mostly masked through company growth.

As I argued recently, I think there’s good reason also to be skeptical of the idea that Amazon’s recent mass layoffs of white-collar employees is about AI displacement. Amazon is by far the largest user of the H-1B visa program, and if its 2025 layoffs are anything like its 2022–23 layoffs, they are adding new H-1B workers at roughly the same clip that they are laying off other workers. On both the white- and blue-collar sides of the equation, the hype is that the “robots are handing out pink slips,” but the reality is much more banal.

To my mind, it’s important to be clear about this because there are any number of excuses I regularly hear about why Amazon is impossible to organize, one of the most prominent being that it’s on the verge of automating away huge swathes of its warehouse/delivery workforce. This is a thought that tickles investors and exercises a disciplining role on labor. Mercifully, it’s not true; unmercifully, it doesn’t need to be true for the company to continue on its path of roaring success, free of union penetration.