Fifty Years Ago, the US Staged a Coup in Australia

The 1975 “dismissal” of Australian Labor PM Gough Whitlam is often seen as a constitutional crisis initiated by an old British-led establishment. In reality, it was a bloodless analog of other US-orchestrated coups against reforming left governments.

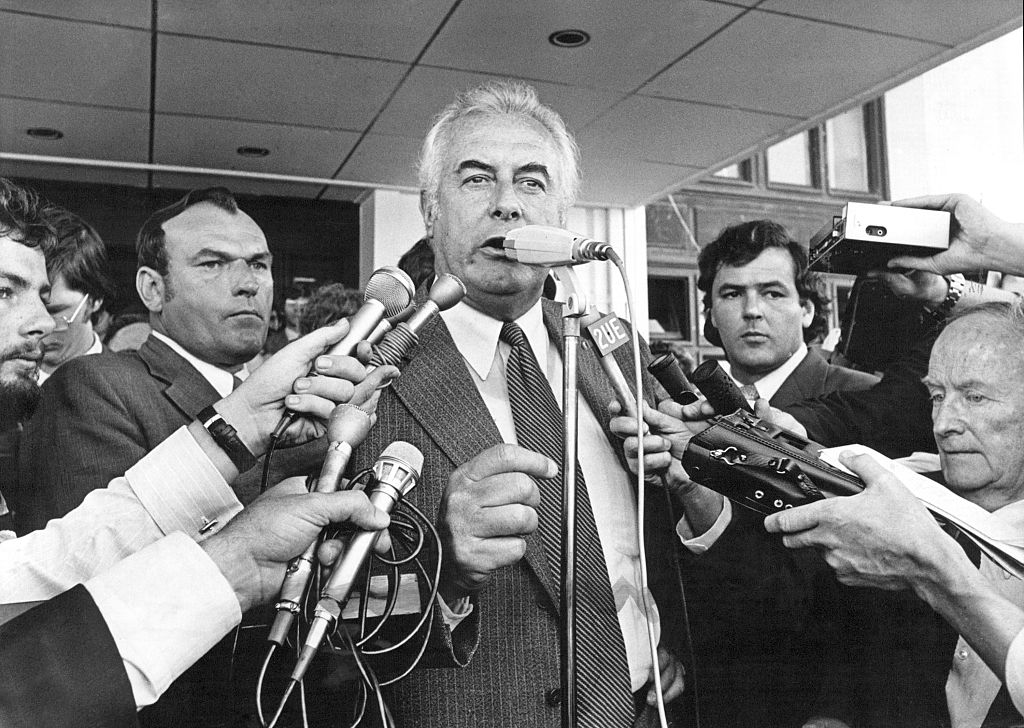

On the morning of Tuesday, November 11, 1975, Governor-General John Kerr summoned PM Gough Whitlam to Yarralumla, the governor-general’s residence, where Kerr handed Whitlam a dismissal letter. (Graeme Thomson / Newspix / Getty Images)

Half a century ago this week, Australia was rocked by the removal of its prime minister, Gough Whitlam of the Australian Labor Party (ALP), by the governor-general, Sir John Kerr.

Whitlam, a solid social democrat by the standards of that time — and as far left a leader as Australia has had since the 1950s — had lost control of the Senate, the Australian Parliament’s upper house. The right wing opposition, a Liberal Party–led coalition, used this advantage to deny the government “supply,” blocking essential government spending.

Although the situation was similar in some ways to a US government shutdown, one important difference is that Australia was, and is, a constitutional monarchy, with the governor-general serving as head of state.

According to decades of convention, the governor-general was supposed to act according to advice supplied by the prime minister. On November 11, however, Kerr dismissed Whitlam, called an election and appointed the opposition leader, Malcolm Fraser, as caretaker PM. A few hours later, he dismissed (“prorogued”) parliament.

On both Left and Right, many like to take the Whitlam dismissal— as it became known — as a constitutional struggle between an old British-oriented establishment and a new, progressive Australia. But in retrospect, it’s hard to doubt that the 1975 dismissal was in fact a soft coup d’état, heavily influenced by US power and influence.

In this conception, which draws the interpretation decisively out of the narrow Anglo-Celtic frame, the dismissal was a bloodless, legalistic event in the chain of coups orchestrated by the United States to shore up domination over a series of client states, from Guatemala and Iran in the 1950s, to South Vietnam in the 1960s, and to Chile in 1973. Indeed, in this reading, the closest analogue to the Whitlam dismissal is the overthrow of Chile’s elected Marxist president, Salvador Allende, who was violently deposed by General Augusto Pinochet after years of CIA and other agency conspiring.

Violence in the Global South and legalism in the Anglosphere: the methods differed but not the substance of events. Fifty years later, the global context and implications of the Whitlam dismissal are, if anything, far clearer.

It Was Time

Gough Whitlam led the Labor party to victory in 1972, after twenty-three years of government by the Liberal Party–led Coalition. The son of a senior public servant, Whitlam was one of the first haute-bourgeois left-liberals to join Labor, which had been a fairly closed, union-dominated party. From 1967 on, however, Whitlam modernized the ALP, opening it to the rising university-educated middle class and initiating a political shift toward the technocratic center, away from Labor’s mid-century industrial, semisocialist program.

Labor’s left faction was a genuine left in those days, fully socialist and opposed to the US alliance. But when it came to foreign policy, the ALP pursued something of a middle way. Labor decisively concluded Australia’s involvement in the Vietnam War and ended cooperation between the Australian Secret Intelligence Service (ASIS, Australia’s international spy agency) and the CIA in Latin America.

Whitlam also made noises about the invasion of Australian agricultural export markets by the United States’ heavily subsidized agribusiness sector. Fatefully, perhaps naively, Whitlam tried to use US spy bases hosted on Australian territory as a bargaining chip in this dispute. “Don’t try to bounce us,” Whitlam said colloquially to the US ambassador in 1973, suggesting that leases on the US bases, set to conclude in December 1975, might not be renewed.

It was a foolish move. Pine Gap, near Alice Springs in Central Australia, was one of three such bases whose southern location and high-tech capability gave America a huge surveillance advantage over the USSR. As a result, the United States saw Pine Gap as crucial to the Cold War projection of power. Created in the early 1960s, it was run by US personnel and barred to Australians, few of whom, Whitlam included, had any idea of its importance.

If this wasn’t bad enough, worse was to come. Already frosty relations with Richard Nixon’s administration took a nosedive at the end of 1972, after Henry Kissinger’s Christmas bombings of Hanoi. Whitlam protested privately while the Labor left, led by deputy leader Jim Cairns, protested publicly, organizing enormous demonstrations decrying the bombings as part of a genocidal war.

The Whitlam–Nixon relationship continued downhill, until things fell apart even further when Whitlam followed up on his stated intent to build closer ties with the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), a Cold War bloc of countries that refused to join either the US or Soviet camp.

In 1973, the Whitlam government invited senior members of the Yugoslav government, one of the leading countries in the NAM, to visit Australia. The Yugoslavs replied that they couldn’t come until Australia had rounded up local Ustaše cells of Croatian fascists who had reassembled themselves in the migrant Croatian community following World War II. The Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) — Australia’s internal spy agency — was accused of dragging its feet, as a way of delaying the visit.

This prompted one of the most extraordinary events of the Cold War, when Whitlam’s attorney-general, Lionel Murphy, ordered federal police to raid ASIO headquarters in 1973 and cart off its files. This, as US counterespionage spy master James Jesus Angleton later told Australian journalist Phillip Frazer, was the last straw. The Nixon administration and the CIA saw shared intelligence as the “crown jewels” of the US-Australia relationship and were now on the hunt to destroy Whitlam’s government.

The Coup Takes Shape

In 1973–74, the US government and the CIA had two pieces of luck. In 1974, Whitlam very foolishly appointed as governor-general an old friend, Sir John Kerr, whom he thought he could easily control.

Kerr was an extraordinary figure; in the 1930s, he was a Stalinist fellow traveler, before becoming something of a Trotskyist. Kerr then served as an aide to Herbert Vere “Doc” Evatt, Labor foreign minister from 1941–49, and also as a liaison officer with the CIA’s precursor, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS).

By the late 1940s, Kerr had completed his Cold War turn, becoming a resolute anti-communist and vying for the leadership of a CIA front group, the Australian Congress for Cultural Freedom. Kerr, of working-class origins, still saw himself as “Labor,” although he believed the party was too infiltrated by the Communist Party of Australia — which controlled a third of Australia’s unions at the time — to work with.

The CIA’s second piece of luck arrived when the Whitlam government encountered trouble trying to secure financing for an ambitious spending program, resulting in a crisis now known as the “Loans affair.” Whitlam’s Labor left treasurer, Jim Cairns, and resources minister Rex Connor were both desperate to increase state development in Australia and were frustrated at UK and public service control of global capital-seeking.

In 1973, the recently formed Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) offered a solution. After the price of oil quadrupled in the early ’70s, the oil producing nations found themselves with vast new incomes they needed to invest. In 1974 and early 1975, Connor turned to Middle Eastern OPEC member states, seeking $4 billion in loans (about 10 percent of Australia’s GDP). Connor’s plan envisaged using the funds to buy out the foreign owners of Australia’s mining leases and using the proceeds to fund a French-style Australian uranium processing industry, creating virtually free energy.

In the aftermath of the Loans affair, Connor was portrayed as a buffoon and a yokel. But he was a visionary and a deeply well-read man, who understood that when it came to production, Labor’s socialism was hopelessly antiquated. At the same time, however, Connor was also naive. When he advertised Australia’s loan tenders in the Asia financial press, it brought out every shady money middleman in the region. Half of them were CIA fronts, created at the height of the Vietnam War.

Connor chose Tirath Khemlani, a Pakistani-born London-based commodities trader, who spent months bouncing around the world, excitedly telling Connor from borrowed telex machines, that the funds were “imminent.” But the funds never arrived.

Meanwhile, by mid-1975, the Opposition had chosen as its new leader Malcolm Fraser, a rural establishment scion, at the time a fan of Ayn Rand, who was dedicated to a more aggressive parliamentary strategy.

In mid-1975, the Loans affair became public knowledge. Although their authority to do so had been revoked by Whitlam, both Cairns and Connor continued to seek loans. This information was first leaked to the Opposition, possibly the result of Pine Gap surveillance.

Then in October, Khemlani turned on Connor and Cairns and leaked telexes between himself and Connor to Malcolm Fraser’s Opposition. It soon became a national scandal. On October 16, 1975, Fraser — who held the balance of power in the Senate — announced he would block supply until a new election was called.

The Coup Gathers Momentum

If the atmosphere in Australian politics had been intense before, it was about to get white hot. Whitlam’s staff began looking for a counterattack — and they found it in Adelaide. Labor figures told Whitlam’s “fixer,” Richard Hall, that they knew a man named Richard Stallings who had been bragging that he was a CIA agent. Stallings was also a friend of Doug Anthony — then leader of the National Country party, the junior member of the Coalition — and was reportedly financially entangled with US interests in Australia. This turned out to be something of an understatement. In fact, Stallings had founded Pine Gap in the early 1960s and was its first head.

More ammunition fell into the Whitlam government’s lap when it discovered that although Stallings’s name was on a list of CIA agents in Australia held by the public service head of the defense department, Sir Arthur Tange, his name was not on the list held by the government itself. Doug Anthony had already threatened to bring it all up in Parliament when it reconvened on November 11, 1975. Whitlam went further, threatening to name other CIA agents in Parliament, although the press outed him before Parliament sat. Regardless, the lease of Pine Gap and other bases was now firmly on the agenda.

Meanwhile, for some time, Governor-General Kerr had been in an extensive, needy, and sycophantic correspondence with Buckingham Palace, thinking out loud about what could be done with the “reserve powers” of the governor-general. Could he act without, or against, prime ministerial advice?

Kerr also took an interest in security matters. In the same period, Whitlam had promptly sacked the heads of both ASIO and ASIS. The former, ostensibly, was fired for having an affair, making him a security risk. Whitlam sacked the latter for breaking his ban against ASIS involving itself in political conspiracy, in this case, by aiding pro-US forces in the newly independent East Timor. Kerr took a “great interest” in the ASIS sacking, which had been so firm, staff later recollected, they could hear Whitlam’s yelling through the door of his office.

The Australian defense establishment now decided it had no alternative but to brief Kerr fully about the function and importance of Pine Gap. In early November, Tange organized a meeting between Kerr and the chief government scientist, John Farrands, a radio physicist by profession and one of the few Australians who knew exactly how Pine Gap worked. Farrands’s briefing left Kerr in no doubt about the importance of Pine Gap, which boasted surveillance capacities beyond anything else at the time.

Then on the weekend before November 11, the ASIO liaison with the CIA’s East Asia desk received a telex from the CIA desk chief, Ted Shackley. It stated that if CIA agents were named in Parliament, intelligence sharing with Australia would cease. The telex circulated in Canberra before being supplied to Kerr.

On the morning of Tuesday, November 11, 1975, as Parliament opened, Kerr summoned Whitlam to Yarralumla, the governor-general’s residence. Whitlam assumed that Kerr wanted to discuss the crisis with him. Instead, Kerr handed Whitlam a dismissal letter. He then appointed Fraser as prime minister and called an election for December 12.

Hours of parliamentary skirmishing followed. When Labor gained the upper hand, Kerr prorogued parliament, dissolving it immediately. This also prevented any possibility that CIA agents would be named in Parliament and blocked any discussion of US spy bases.

After becoming caretaker prime minister, one of Fraser’s first acts was to renew the leases on the US bases, which had been due to expire on December 9, just three days before the election.

Aftermath

Labor ran in the election as an opposition, campaigning on democracy and legitimacy and was defeated in a landslide. It signaled the end of any possibility of social democratic reform backed by a strong union movement.

Malcolm Fraser served as prime minister for eight years, loyally supporting US foreign policy, save for its uncritical support of apartheid South Africa. He also ushered in the new “Echelon” system, which distributed Pine Gap surveillance capacity across the nation and was a forerunner to the total surveillance systems that Wikileaks and Edward Snowden exposed in 2013.

In 1978, the Hope royal commission, inaugurated by Whitlam, delivered findings suggesting that funding for intelligence services should be cut and that they be subject to more stringent oversight. However, all talk of intelligence curtailment ended after a terrorist bombing outside an international meeting in Sydney killed two people in February the same year.

In the aftermath of the Whitlam coup, Labor plunged into five years of brutal factional warfare, especially in Sydney, where branch stacking and intimidation escalated to beatings and murder by elements in the New South Wales right. By the early 1980s, it was all over, and the Right was triumphant.

Former Australian Congress of Trade Unions secretary Bob Hawke, soon to be prime minister, made it clear that a Labor government under his leadership would maintain the US alliance. Hawke would also keep Australia part of the Five Eyes intelligence-sharing arrangement with the UK, the United States, Canada, and New Zealand. He also promised that no natural resources would be nationalized and that his government would make no attempt to bypass standard capital markets, as Jim Cairns and Rex Connor had done.

In 1983, Labor returned to power, and Hawke implemented a neoliberal regime that was, with few exceptions, to the right of the Fraser government’s agenda.

The Afterlife

From 1975 until the mid-1980s, there was white-hot indignation at US interference in Australian politics. But with the passing of time, memory of the dismissal has changed.

With the global collapse of the Western left in the early 1980s, it became less common to read history in light of an international framework, a shift that only accelerated after the end of the Cold War. Previously US influence and Pine Gap had been central parts of the national political discourse. Increasingly, however, discussion of these issues became isolated to the explicitly activist, “inner-city” left, a Left that, moreover, found itself increasingly severed from the organized working class.

While the constitutional questions raised by Whitlam’s dismissal remained unresolved, the narrative came to be shaped by a new Labor left worldview that reframed the story as a struggle between a residual British establishment and the left-nationalist vision of Australia held by a rising knowledge-based middle class. Indeed, a mid-1980s TV miniseries about the Whitlam dismissal didn’t so much as mention the national security crisis or US influence.

This shift in the discourse was, in part, the result of an effort to consciously scrub the record. Over four decades, for example, Paul Kelly, a lifer editor-journalist in Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp, has published four editions of his record of the time, The Unmaking of Gough. The first edition is from a time when Kelly led a strike at News Corp masthead the Australian against the paper’s biliously biased coverage of the event. In it, the “national security crisis” gets its own chapter. By the third edition, the chapter had disappeared. In the renamed fourth edition, edited by Troy Bramston, he and Kelly explicitly ask the CIA whether it had had any role in the dismissal. As the authors primly report, the answer was “no.” Just fancy that.

One source of resistance to an understanding of the US and CIA involvement in the Whitlam dismissal stems from a piece of misdirection promoted by the Right, which suggests — and refutes — the straw man argument that the CIA directly instructed Kerr to sack Whitlam. No one, however, has seriously suggested this was the case. Nor does it need to be. Like the 1954 deposition of Mohammad Mossadegh in Iran, US forces took advantage of blunders committed by local parties while reaping the benefits of longer-term work. Part of this work involved cultivating lifelong assets like John Kerr, who shared the CIA’s antidemocratic Cold War outlook.

And now, fifty years later, it’s absurd to deny CIA involvement. Doing so requires us to turn a blind eye to the fact Whitlam was sacked in the morning of the very day on which CIA agents were to be named in Australia’s Parliament. It requires us to ignore that the Whitlam government was considering the closure of US bases and that the US alliance was under enormous public pressure. And denying US involvement means ignoring the fact that a former CIA asset sacked Whitlam after seeing a CIA telex spelling out the fatal risk he posed to US interests in Australia.

This is why the Whitlam dismissal shouldn’t be thought of as a “dismissal” but rather as a bloodless, legalistic Cold War coup: a polite, Anglophone version of Allende’s overthrow in Chile in 1973. The goal was to reassert control over a nation that, however moderately, had sought to assert its independence and interests. And that is how the Whitlam coup will be seen in decades to come.