Mamdani Can Learn From Latin American Municipal Socialism

From 2005 to 2016, against the wishes of both the country’s ruling and opposition parties, the small Venezuelan municipality of Torres underwent a radical experiment in democracy, giving residents direct power over the budget. It worked.

From 2005 to 2016, the municipality of Torres in Venezuela was one of the most deeply democratic cities in the world. A Zohran Mamdani mayoralty could learn from its example. (Michael M. Santiago / Getty Images)

If you’re looking for successful cases of municipal socialism, Torres, a municipality in the Venezuelan state of Lara, deserves to be high on the list. From 2005 to 2016 Torres was one of the most deeply democratic cities in the world. During these years, ordinary citizens exercised an extraordinary level of control over local political decision-making. Their most powerful tool? A participatory budget, which gave residents binding control over the full municipal investment budget.

In district-level assemblies, predominantly working-class participants (agricultural laborers, domestic caregivers, small farmers, students, teachers, and others) thoughtfully weighed the merits of spending their limited funds on various projects. There was no exclusion based on class, race and ethnicity, gender, religion, or political views, with both ruling and opposition party supporters participating. Turnout was massive, with between 8 and 25 percent of Torres’s population of 185,000 taking part in the process. In addition to providing actual popular control over decision-making, Torres’s Participatory Budget simply worked. Decisions were effectively linked to outcomes, with over 85 percent of projects completed in a timely manner. And the process benefited the local incumbent party, which was subsequently reelected multiple times.

Torres’s success and the way it was achieved offer important lessons to democratic socialists elsewhere, including the one very likely to be New York City’s next mayor. In fact, there are striking parallels between the rise of Zohran Mamdani and Torres’s mayor Julio Chávez. Like Mamdani, Julio (as he is universally called in Torres) entered his race for mayor, in 2004, as a long-shot far-left candidate backed by a social movement party and facing the incumbent mayor and other powerful opponents supported by both Hugo Chávez’s national ruling party and local elites. Like Zohran, Julio was given little chance to win, and like Zohran he surprised everyone by doing just that.

Once in office Julio sought to make good on his campaign promise to “build popular power.” In an interview he elaborated on this goal, which he linked to socialism:

We say all expressions of socialism should be based on the people’s participation, a participation that impedes bureaucratism. . . . This socialism should start with the idea of constructing popular power . . . [and be based on] projects that make visible the process of governing with the people, not for the people, so that decisions are taken by the people. . . . We’d rather err with the people than be right without the people.

Julio’s remarks point to one of two factors key to his administration’s success, which was built, first, on adapting and repurposing the ruling party’s discourse, laws, and institutional forms. By this I mean an opposition party that utilizes the ruling party’s political toolkit — the ideas, laws, and practices by which it rules — in different ways and for different purposes. During the Hugo Chávez era, ideas about participation, popular power, and socialism became discursively and institutionally central throughout Venezuela. When he was elected mayor, Julio Chávez was not a member of the ruling party, the Fifth Republic Movement, but he actively utilized ideas, laws, and organizational forms associated with Chavismo, such as participatory budgeting, communal councils, and socialism. Crucially, however, Julio’s administration embedded these ideas and organizational forms in a local framework that differed from the national one in critical ways. These included strong respect for political pluralism, a genuine commitment to popular control over decision-making (with the necessary institutional mechanisms required to ensure it), and institutional effectiveness, in which the local government genuinely delivers on its promises.

The second key to Torres’s success was the administration’s links to highly mobilized and organized popular classes. Julio was clear about where he stood in the class struggle, saying, “the oligarchs had forty years ruling here and always controlled the local authority.” His administration, by contrast, proudly aligned itself with popular classes, and actively worked to redistribute wealth and resources from the rich to the poor. One of Julio’s first mayoral acts was to eliminate a lifetime pension paid to the head of the local church, which was very conservative and aligned with the oligarchy, and to reallocate the funds to indigent seniors. In coordination with the National Land Institute, Torres’s City Hall expropriated five large haciendas, totaling over fifteen thousand hectares. Julio said, “We hope to return [land] to the hands of those who’ve always owned it, peasants of the zone. . . . We’ve undertaken a war against latifundios, the struggle for the land.” Julio spoke proudly of “municipalizing the fairgrounds,” which he said only “the oligarchy [had previously] utilized. . . . Small peasants can now go and display their goats with pride, the same peasants and goat breeders who [cattle ranchers] have always contemptuously called ‘chiveros.’” Popular democratic commitments like this are notoriously hard to reverse, with Edgar Patana, Julio’s successor as mayor, pledging “unconditional support for small and medium producers.”

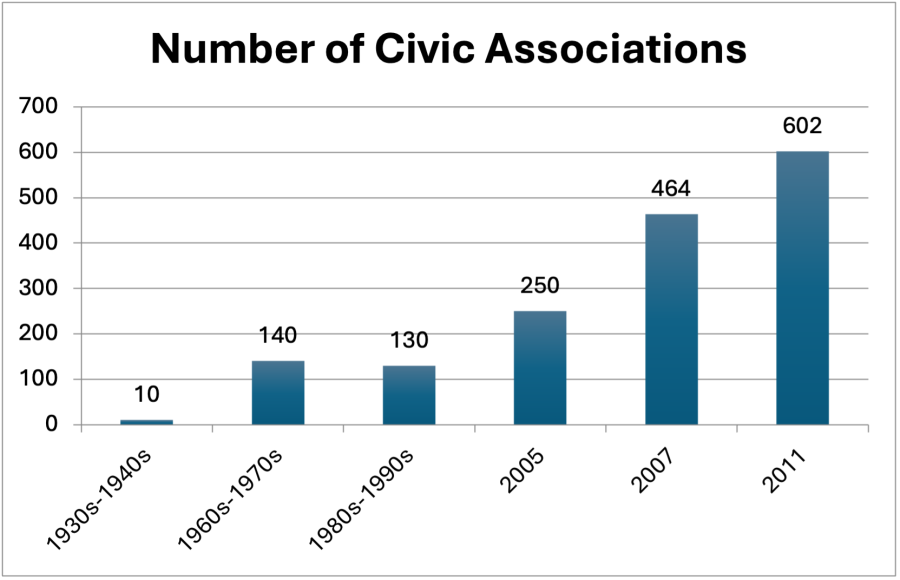

Torres’s City Hall led a major effort to organize and mobilize residents, spearheaded by the Office of Citizenship Participation. The success of this effort was aided by the movement trajectories of key state officials who joined the administration after years and often decades of social movement leadership and organizing. Lalo Paez, who like the mayor and many other top officials was a former social movement leader, headed the participation office, which was located in the recently municipalized fairgrounds. Lalo and his team first organized communal boards and later organized and registered communal councils and communes. This facilitated a boom in civic associationalism, as shown in Figure 1, and was a boon to popular power in Torres.

During Julio Chávez’s first two years as mayor, he faced repeated resistance from the ruling Fifth Republic Movement, which had opposed his candidacy. But this strategy soon backfired with Julio mobilizing his popular-class base against their obstructionism. The result was an even stronger link between City Hall and popular classes. In June 2005, Torres’s municipal council, under the control of the ruling party, refused to approve an ordinance recognizing the results of Torres’s municipal constituent assembly, a participatory process that rewrote Torres’s ordinances. In response, the mayor mobilized hundreds of supporters to occupy City Hall and pressure the council to reverse its decision. The ordinance was finally approved in late 2005, after an election in which councilors more favorable to Julio gained a majority. The mayor also mobilized supporters in December 2005 when the council refused to support the participatory budget. In May 2008, Julio tried to get on the ballot to run for governor as a member of the United Socialist Party of Venezuela, which Julio joined when it was formed by Chavistas in 2007. Regional party leaders blocked this move. Julio responded by bringing hundreds of his supporters to the party’s regional office. This worked, and the party let Julio run.

These examples show how popular organization and mobilization very literally undergirded and made Torres’s municipal socialist experiment possible.

What Torres Can Teach Us

Torres holds two major and three minor lessons for a Mamdani administration. The first is the usefulness of a local opposition party that refracts the national ruling party’s political toolkit. Mamdani has already learned this lesson well. He regularly references President Trump’s 2024 campaign promise to lower the cost of living and the manifold ways in which Trump’s policies have failed to do this. Mamdani then outlines how his own signature policies — freezing the rent, making buses fast and free, and establishing universal childcare — will do some of what Trump promised but has utterly failed to deliver.

The second key lesson is the importance of organizing and mobilizing the working class, understood in a broad sense. Torres’s success in facilitating an extraordinary degree of popular control over local political decision-making and redistributing resources from rich to poor rested on the organization and mobilization of the working class. This was done in a highly inclusive, deliberately nonpartisan way. It was crucial to Julio Chávez’s ability to overcome the resistance of local and regional political elites, many of whom were leaders of Venezuela’s national ruling party. When these elites sought to block the mayor’s participatory and redistributive policies, he responded by repeatedly mobilizing his working-class base.

Since he became a serious candidate, Zohran has faced significant resistance from the Trump administration, as well as local, state, and national Democratic Party leaders. And it’ll only get worse after he takes office. Trump, other Republicans, and many Democrats will do everything they can to block Zohran’s key policies and his preferred solutions for funding these policies, such as modestly increasing taxes on corporations and the rich. To overcome this resistance, Mamdani will need to organize and mobilize his working- and middle-class base, to wage a struggle inside and outside the state. There are already proposals by scholar-activists like Eric Blanc about ways to do this. Torres’s experience suggests that organizing ordinary citizens in a nonpartisan way — and in a way that gives them real power over decisions that matter to their lives — can be an effective strategy. Torres also shows how working-class direct action, orchestrated by reformist state officials, can effectively counter intransigent elite opposition.

A third, more minor lesson is the importance of having state officials with movement trajectories — that is, people who come to office with long experience in social movement organizing and leadership. This was key to Torres’s success in several ways. First, these officials knew the importance of popular organizing and how to do it. Second, the officials had long-standing links to popular organizations. And third, these officials were ideologically committed to a vision of democratic socialism in which, as Julio Chávez said, “the people make all the decisions.” Through his links to the Democratic Socialists of America and many popular organizations, Mamdani is well positioned to put movement leaders into key positions in his administration, but he is already facing significant pressure to put more traditional leaders in high posts. Ensuring that experienced movement leaders are present throughout his administration, particularly in top posts, remains vital.

Another lesson concerns institutional design, and specifically the design of participatory institutions. As other scholars have shown, participatory institutions don’t always connect to the real decisions that actually matter to people’s lives or simply don’t give them effective control over these decisions at all. Torres’s participatory institutions not only worked but actually fostered democratic socialism because (a) they focused on issues that mattered deeply to people’s lives; (b) they gave people real control over these decisions, with institutional mechanisms ensuring that even when officials sought to influence decisions — as they frequently did — it was citizens who had final say; and (c) they involved citizens in deliberative discussion and thus created a learning process in which, to quote Torres official and social movement leader Lalo Paez, “the people are the government.” Zohran has said little about fostering participatory decision-making, but if and when his plans to do this are revealed, the question of institutional design must be front and center.

The final lesson points to exactly why Zohran must consider taking a page from the Torres playbook: participatory institutions not only contribute to institutional effectiveness, they can, in turn, foster political effectiveness. I saw this clearly during my research in Torres. Citizens said they were initially skeptical of Torres’s Participatory Budget but came to trust it after seeing results year after year. Torres’s Participatory Budget also proved a highly effective tool for generating popular consent. When I provocatively asked residents in Participatory Budget assemblies, “Why not just leave this to the mayor?” I often heard replies like the following: “In the past government officials would stay all day in their air-conditioned offices and make decisions there. They never even set foot in our communities. So, who do you think can make a better decision about what we need? An official in his air-conditioned office who’s never even come to our community, or someone from the community?”

In a moment of rising authoritarianism — nationally and globally — much is riding on Zohran’s success. Taking account of the lessons of Torres and other cases of municipal socialism can help Zohran and all who support him make the most of this unprecedented opportunity. We have a chance to not only make New York City more affordable but also, as Zohran said in his closing campaign rally, to “set ourselves free.”