It’s Still Possible to Rebuild a Working-Class Majority

Labor organizing can’t succeed at scale without a supportive legal and political environment, created by majoritarian coalitions that can win reforms, confront corporate power, and prove to skeptical workers that progressive governance delivers.

Economic populism works, but only if voters know a candidate is willing to confront elites and making working-class economic priorities central to their message. (Victor J. Blue / Bloomberg via Getty Images)

What is the best way to build working-class power when labor’s leverage over capital is near a historic low? With private-sector union density at just 5.9 percent, the structural weakness of the labor movement imposes severe limits on progressive political possibilities in the medium term. Rebuilding labor must be a central priority of any long-term strategy. But even the most innovative organizing efforts — alongside promising tactics like ballot initiatives or worker cooperatives — cannot, on their own, deliver a major shift in class power.

Such a breakthrough requires favorable political conditions and a large working-class base that sees the value of both unions and strong government programs to expand economic security. In other words, labor organizing cannot succeed at scale without a supportive legal and political environment — one created by majoritarian coalitions capable of enacting reforms, confronting corporate power, and proving to a skeptical working class that progressive governance delivers. That kind of transformation will take years, even decades. But in the short term, building political power for working people — especially in purple and red states — is essential.

To make this possible, progressives must prioritize an economic populist approach, led by credible — ideally working-class — candidates and anchored in durable local infrastructure, particularly in the regions where they have struggled most.

Why Progressives Must Rebuild Support Among the Working Class

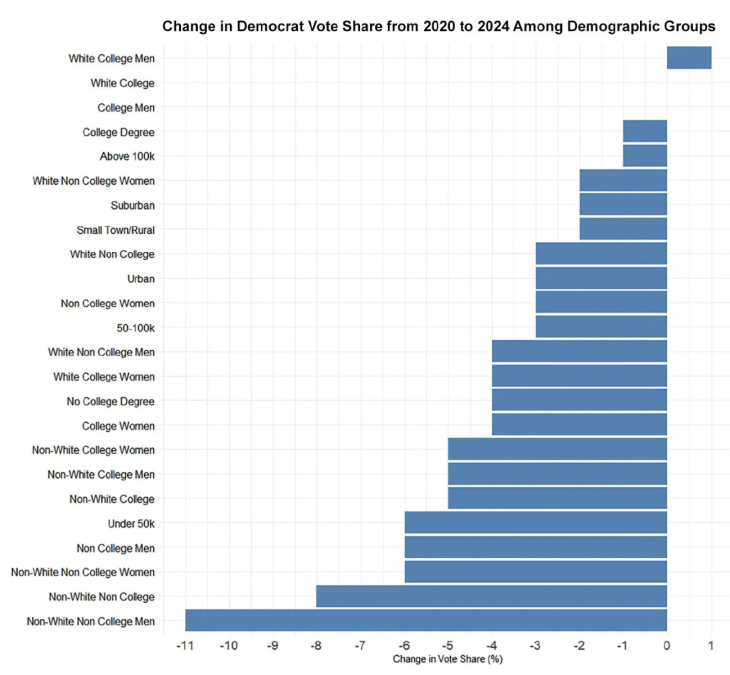

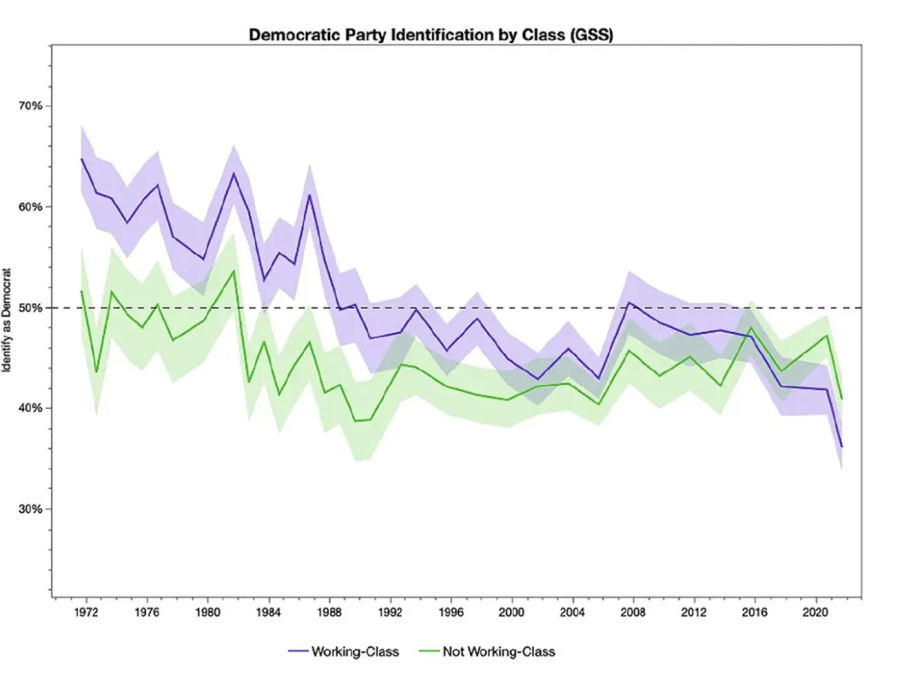

Progressives cannot afford to ignore the political consequences of working-class dealignment from the Democratic Party. While the magnitude of this shift varies depending on how the working class is defined, the underlying trajectory is consistent and alarming. Class dealignment is real and increasingly multiracial, especially since the 2024 election when non-white men shifted decisively toward the Republican Party.

Working-class dealignment matters for several reasons. First, it makes it much harder for progressives to win national elections. The structure of the US political system — particularly the Electoral College and the Senate — gives disproportionate power to states with large working-class electorates. Without winning back significant numbers of these voters, progressives are unlikely to secure durable governing majorities. In 2020, working-class voters (defined as those without a four-year college degree) made up the majority of the electorate in all five key swing states — and working-class whites alone constituted outright majorities in Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. According to my analysis of Cooperative Election Study data, Joe Biden’s gains among working-class voters in Arizona and Georgia from 2016 to 2020 were 2.3 and 8.5 times larger, respectively, than his overall margin of victory in those states. Similarly, American National Election Study (ANES) data show that 72 percent of battleground state voters who switched parties between 2016 and 2020 were noncollege graduates. Without holding or expanding their current share of the working-class vote, Democrats’ odds of winning national majorities remain slim.

But the stakes go beyond electoral math. As political commentator Andrew Levison has argued, ceding the traditional working class to Republicans deepens the far right’s hold over communities where progressive voices have already grown scarce. In red, working-class districts, the absence of credible progressive alternatives enables the spread of far-right narratives — not just at the ballot box, but through churches, schools, social media, and everyday conversation. Once progressive ideas disappear from the local political culture, it becomes significantly harder to reestablish them. The result is a self-reinforcing cycle of alienation and extremism that threatens the social fabric and increases the political cost of inaction.

There are also policy consequences to dealignment. As the political scientist Sam Zacher has shown, an increasingly affluent Democratic coalition is likely to be less supportive of redistributive economic policies. While wealthier Democratic voters may voice support for social insurance in abstract terms, their commitment weakens when policies would require them to pay higher taxes. In contrast, working-class voters consistently demonstrate stronger and more intense support for economic populism — especially when policies involve real redistributive stakes. Shifting the Democratic base further toward the professional-managerial class risks undermining the very agenda progressives seek to advance.

Lessons for Effective Progressive Electoral Strategy

If building progressive working-class electoral majorities is a necessity, the next question is how to do so most effectively. In the following parts of the article, I propose four key elements of a progressive electoral strategy for winning working-class votes, based on a wealth of research my colleagues and I have conducted at the Center for Working-Class Politics, as well as a range of other scholarly insights.

- Run Economic Populists

If progressives hope to reverse the Democrats’ decades-long erosion of working-class support, they need more than vague appeals to “hard-working families” or technocratic promises of incremental reform. They need to run candidates who unapologetically embrace economic populism: candidates who center the struggles of working people, and who name and confront corporate power, in raw, unfiltered, and unapologetic terms. A growing body of empirical evidence — from survey experiments to real-world election results — shows that economic populist candidates consistently outperform more centrist or establishment-aligned Democrats, particularly in the working-class districts where the party is struggling most.

Economic populist messaging is distinguished by two core features: (1) celebrating the contributions and dignity of working people and (2) forcefully challenging the power of economic elites — billionaires, corporate monopolies, and Wall Street interests — that have rigged the system for themselves. This messaging works not only because it taps into widespread frustration but also because it offers a clear moral story of conflict: ordinary people versus the forces that exploit them. It provides clarity and agency, unlike the abstract appeals to unity or democracy that often define moderate campaigns.

The clearest exemplar of economic populism over the last decade is Senator Bernie Sanders, whose 2016 and 2020 presidential bids paired relentless attacks on corporate power with a plainspoken defense of working people. In one of countless versions of this formula, Sanders exhorted at a 2023 rally of striking autoworkers that

the fight that you are waging here is not only about decent wages, decent benefits and decent working conditions in the automobile industry. No. The fight you are waging is a fight against the outrageous level of corporate greed and arrogance that we are seeing on the part of CEOs who think they have a right to have it all and could [not] care less about the needs of their workers.

But Sanders is far from the only progressive economic populist in US politics today. Democratic Congressman Chris Deluzio of Pennsylvania, for example, exemplified the economic populist approach in his successful 2022 campaign in western Pennsylvania. A Navy veteran and union organizer, Deluzio held onto a tightly contested swing seat with a message that explicitly named corporate power as a threat to democracy and working-class prosperity. As he put it:

I believe in fighting for our common good, for our shared prosperity, for a government that serves all of us — not just the biggest and most powerful corporations. We should be making things in this country, right here in western Pennsylvania with our union brothers and sisters doing the work.

Research by the Center for Working-Class Politics has consistently found that economic populist messaging is more effective in reaching working-class voters than alternative approaches. For instance, our experimental test of thousands of hypothetical candidate profiles in 2023 found that working-class voters preferred candidates who “pit ‘Americans who work for a living’ against ‘corrupt millionaires’ and ‘super-rich elites,’ while other occupational groups exhibit no discernible distaste for them.” Similarly, a late 2024 poll we conducted among Pennsylvania voters testing a range of actual and potential Harris messaging found that strong economic populist messaging — featuring bold, anti-corporate rhetoric and ambitious economic policy — was the most effective messaging frame tested among all voters—including compared to Harris’s actual economic messaging. And critically, we find no evidence that the strong economic populist message turned off other important Democratic constituencies such as higher-income, highly educated, or professional-class voters.

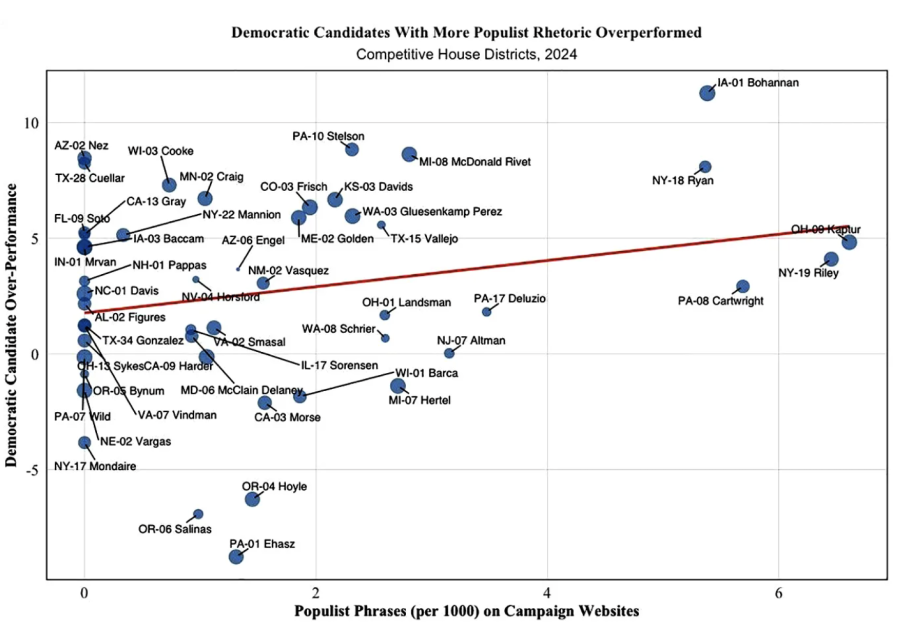

In addition to our survey research, our analysis of the actual campaign messaging of all Democratic candidates in 2022 found that working-class voters respond more favorably to economic populist candidates than to other candidates. On average, economic populists running in 2022 outperformed their nonpopulist counterparts by 12.3 percentage points in primarily white, noncollege districts, 6.4 percentage points in districts with high concentrations of working-class occupations, and 4.7 percentage points in rural and small-town areas.

These results are supported by our initial analysis of 2024 Democratic congressional candidates in key swing districts, which shows that Democrats who employed anti-economic elite rhetoric in competitive House races outperformed baseline expectations by nearly three percentage points more than candidates who steered clear of populist attacks on economic elites.

Despite this evidence, many Democratic leaders remain resistant to economic populism. For instance, Kamala Harris, who occasionally invoked corporate price-gouging and supported a range of solidly progressive economic policies that would have helped working people, failed to deliver a robust economic populist message that working-class voters could find credible. To the contrary, as the 2024 campaign wore on, Harris increasingly turned away from economic populism and toward a focus on Trump as a threat to democracy — which, while true, did not signal to working-class voters that Harris was focused on the basic economic issues that working-class voters consistently prioritize as their chief concerns. The result is a messaging vacuum that has allowed the Right to dominate the populist terrain — even when Democrats have the better policy solutions.

- Run Working-Class Candidates

Despite comprising a majority of the US population, working-class Americans remain starkly underrepresented in elected office. Political scientist Nicholas Carnes estimates that just 2 percent of members of Congress and 3 percent of state legislators come from working-class occupational backgrounds, and my analysis of a database maintained by the Center for Working-Class Politics (CWCP) of all congressional candidates between 2010 and 2022 shows that less than 6 percent of general election candidates held working-class occupations for at least half of their pre-political careers. This disconnect between the socioeconomic profile of elected officials and the people they represent has wide-ranging implications for elections and beyond.

Recent research underscores the electoral value of electing working-class candidates. In our analysis of a large-scale survey experiment from 2023, CWCP research associate Fred DeVeaux and I found that working-class voters are significantly more likely to support Democratic candidates with working-class occupational histories, all else being equal. Working-class respondents preferred such candidates by 6.4 percentage points over those with elite professional backgrounds, and we found that the primary cause driving this effect was that working-class respondents were more likely to say these candidates better represent “people like me.”

The class gap in representation matters not just for short-term electoral reasons but also because working-class candidates are typically stronger advocates for working-class issues. In a new working paper, DeVeaux and Abbott analyzed all general and primary election candidates for Congress from 2010 to 2022 and found that those from working-class backgrounds consistently used more pro-worker rhetoric than other candidates. These findings echo a larger body of research showing that working-class politicians tend to support more left-leaning economic policies than their elite counterparts and that executives with elite backgrounds are more likely to pursue fiscally conservative agendas and limit redistributive spending.

- Run on a Bold Progressive Economic Platform

A growing body of evidence confirms that working-class voters support a wide range of progressive economic policies — from raising the minimum wage to taxing the rich, from expanding public investment to strengthening unions. Contrary to the stereotype of the working class as economically conservative, a large majority of working-class Americans support a range of progressive economic policies. Data analyzed by the CWCP across the General Social Survey, ANES, and Cooperative Election Study from 2021 and 2022 show that 87.9 percent of working-class respondents favored lowering prescription drug prices, 67.9 percent supported increasing taxes on the wealthy, and 69.1 percent backed import limits to protect U.S. jobs. Support for public investment was similarly strong: 64.8 percent of working-class respondents supported increased state spending on education, and 54.8 percent favored a federal jobs guarantee. Support for strengthening worker power was also robust, with 70.5 percent in favor of raising the minimum wage, 68.8 percent in favor of placing workers on corporate boards, and more than half expressing favorable views toward unions.

But support for these policies does not automatically translate into votes for Democrats. To make these preferences politically meaningful, candidates must prioritize economic issues and present them in a way that cuts through the noise of culture war discourse. Experimental research conducted by the CWCP shows that when candidates foreground “bread-and-butter” concerns — jobs, wages, health care, and cost of living — and speak to them in plain, universal terms, they perform significantly better among working-class voters than when they lead with other issues. Similarly, a 2023 CWCP report found that candidates who campaigned on a federal jobs guarantee were viewed favorably across nearly all voter groups — not only by Democrats but also by independents, Republicans, Black voters, swing voters, low-propensity voters, non–college-educated voters, and rural residents. Among the thirty-six combinations of messaging and policy tested, the single most popular candidate profile featured a strong economic populist rhetoric paired with a federal jobs guarantee — highlighting the broad, cross-partisan appeal of ambitious jobs-focused platforms. This finding underscores the potential power of combining bold progressive economic policies with populist messaging that clearly identifies the economic elite as the source of working-class pain.

Despite the popularity of many progressive economic policies, they are often not salient enough to reach working-class voters, in part because most Democrats fail to emphasize these issues forcefully on the campaign trail. This allows conservatives to fill the void with cultural wedge issues. As recent research by the political scientist Jonne Kamphorst demonstrates, when working-class voters believe that economic issues are not a priority for left-leaning parties, those parties lose political support. But when voters are presented with clear information about the economic priorities of progressive parties, their support for those parties increases. The implication is clear: economic populism works, but only if voters know a candidate is running on it — and if campaigns make economic priorities visible and central to their message. Yet far too few candidates are doing so. CWCP’s analysis of 2022 Democratic congressional campaigns found that only around 25 percent of candidates mentioned good, high-paying, living wage, or union jobs in their messaging, about 5 percent of candidates mentioned a $15 minimum wage, and just 3 percent mentioned a jobs guarantee.

All that said, progressives face a hard strategic truth: the policies that are essential to address working-class dealignment in the long term by delivering large-scale material gains that reverse decades of neoliberal austerity — industrial policy, union revitalization, a jobs guarantee, etc. — may not be unpopular in surveys, but nor are they deeply entrenched priorities among working-class voters. But that is precisely why progressives must lead, not follow. This does not mean simply ignoring useful polling data that can help to frame their messaging as effectively as possible, of course, but political opinion is not fixed; it is shaped by leadership and narrative. Just as Donald Trump moved much of the Republican base to the right on important social issues, progressive candidates can also shape public perceptions around economic issues by doggedly and consistently elevating them on the campaign trail. As a recent study by economist Gábor Scheiring and colleagues shows through a comprehensive meta-analysis of the political impacts of globalization, the roots of right-wing populism lie in decades of economic dislocation, and the most effective way to weaken its appeal is to offer credible, ambitious policies that address that material insecurity at its core.

To do that, Democrats cannot keep recycling Clinton-era bromides about tax cuts for the middle class or modest education funding increases paired with spending reductions that are currently on offer by centrist Democrats. These policies have utterly failed to reverse working-class realignment toward the GOP — or to deliver anything close to the level of material improvement that would inspire renewed trust in government. Instead, progressives must advance a comprehensive agenda to improve long-suffering working-class lives and communities. This means rejecting the trade, tax, and deregulation policies that hollowed out working-class communities and advancing bold investments in infrastructure, manufacturing, job training, and public employment. It also requires restoring worker power through stronger labor laws, penalties for union busting, and giving workers a voice in corporate decision-making.

- Reject Both Trump Lite and Trump Rope-a-Dope

In trying to win back working-class voters, Democrats face two tempting but ultimately misguided strategies: adopting conservative cultural positions to triangulate the most effective language for maximizing their short-term poll numbers or standing back and hoping Trump self-destructs. Both approaches have failed before — and both risk compounding the party’s political problems rather than solving them.

The first trap is “Trump Lite” — the belief that by co-opting Republican rhetoric or policy on culture war issues, Democrats can win over skeptical working-class voters. This strategy not only means abandoning important constituencies in the progressive coalition but also shows little evidence of long-term electoral effectiveness.

Of course, candidates must be thoughtful about the specific dynamics of their districts, recognizing that messaging strategies and policy emphases that are effective in one context may be counterproductive in another. That said, a range of evidence casts doubt on the notion that center-left candidates tend to benefit electorally by moderating their policy positions, or conversely, that they suffer electorally by taking more progressive ones. As a result, there is no reason for progressive candidates, even those running in highly competitive districts, to support policies that undermine core progressive principles at the altar of political expediency. This is exactly what a group of congressional Democrats with otherwise strong economic populist credentials did in January 2025, when they cast votes in support of the Laken Riley Act, a bill that would penalize jurisdictions that do not cooperate with US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). In an apparent bid to seem tough on immigration, these Democrats caved on a critical issue of basic civil rights even though it is not at all clear they needed to politically.

Instead of pandering, progressive candidates should find ways to engage culturally skeptical voters on their own terms — without ceding ground on their core beliefs. Arizona Governor Katie Hobbs offers a compelling example. In April 2025, Hobbs vetoed SB 1164, a Republican-backed bill that would have mandated that every police department and sheriff’s office in the state comply when ICE asks them to hold onto a prisoner. Although taking this stance in a border/swing state could be politically risky, Hobbs grounded her opposition in widely relatable terms, framing the bill as federal overreach into local affairs. “Arizonans, not Washington, DC politicians, must decide what’s best for Arizona,” she wrote. At the same time, she did not dismiss the importance of border security — a top concern for many Arizona voters. In her veto message, Hobbs emphasized her administration’s ongoing efforts to address those concerns, noting, “I have worked productively with the federal government to secure our border, stopping fentanyl at our ports of entry through Task Force SAFE, disrupting cartel operations . . . and working across all levels of government to keep communities safe.” In doing so, Hobbs was able to defend immigrants against Republican attacks while remaining responsive to her constituents around border security.

The second trap is what James Carville recently advocated for and described as a “rope-a-dope” strategy: allow Trump to punch himself out while Democrats hang back, absorb the blows, and coast to midterm victories. But this strategy simply represents a form of Clinton-era Third Way politics updated for the Trump era — defined not by a bold agenda to advance working-class interests, but by a posture of passive resistance.

This strategy fundamentally misunderstands both the nature of contemporary right-wing politics as well as progressives’ difficulties with working-class voters. Trumpism is not a self-limiting phenomenon that will collapse under the weight of its own contradictions. On the contrary, the Right thrives in conditions of elite complacency and a rhetorical vacuum from the opposition. Carville’s approach leaves progressive candidates without a compelling message of their own — reinforcing the widespread perception that Democrats stand primarily for opposing Trump, not fighting for working people.

Invest in Infrastructure and Long-Term Engagement

Another necessary step toward rebuilding working-class political power is for progressives to stop treating campaigns as one-off marketing blitzes and start building lasting political and civic infrastructure — particularly in purple and red states where skepticism of progressives is the strongest. That means investing in real, ongoing relationships with communities — through year-round organizing, visible public service, and trusted local leadership. Campaigns should not be isolated events; they should serve as entry points to deeper engagement and institution-building that lasts well beyond the Election Day.

An interesting model for this approach comes from the Rural Urban Bridge Initiative (RUBI), whose Community Works program operates pilot projects in low-income rural counties in Virginia and Georgia. These projects aim to strengthen social bonds and meet immediate local needs by organizing food drives, distributing safety equipment like smoke detectors, coordinating neighborhood cleanups, and hosting blood donation events. While these activities are intentionally nonpartisan and service-oriented, they are quietly sponsored by local Democratic Party officials. The goal is to reestablish a visible, positive presence in communities that have long been politically neglected. Over time, the hope is that residents who engage in these efforts — especially nonvoters, independents, and former Democrats — will find new reasons to see themselves as part of a progressive political project. So far, the programs have drawn interest from a diverse cross-section of people, including disillusioned former Democrats and civic-minded conservatives alarmed by the decline of their communities.

Progressives must think not just about winning votes but about rebuilding a permanent presence in left-behind areas of the country. That means fielding locally grounded candidates even in Hail Mary districts, opening offices that do not close between election cycles, and engaging in practical community work that demonstrates an organic presence in and long-term commitment to the community.

Of course, building this kind of infrastructure is a massive undertaking. Neither the Democratic Party nor organized labor currently has the institutional strength to replicate the kind of local presence unions once enjoyed in working-class communities. That said, part of the problem is tactical: even modest resources are rarely used to build long-term organizing capacity. For example, Democrats spent upward of $4.5 billion on advertising in the 2024 election cycle. Redirecting just 5 to 10 percent of that would provide tens of millions of dollars in seed money to fund robust, localized outreach efforts in hard-to-reach communities and generate momentum that can be built upon over time.

Building a Durable Working-Class Majority

Rebuilding working-class power in an era of labor weakness will require a multipronged strategy — one that acknowledges the limits of existing organizing models and meets the scale of the political and economic crisis head-on. While labor organizing, ballot initiatives, and experiments in participatory democracy all have important roles to play, none are likely to produce transformative change at scale without a complementary push in the electoral arena. As the examples of the 1930s demonstrate, it is often electoral victories and structural reforms — spurred by bold, popular movements — that lay the groundwork for organizing breakthroughs. In today’s context, that means electing economic populists who can champion and enact policies that improve the material lives of working-class Americans and, in doing so, rewire their expectations of government and their relationship to politics. This is not a matter of choosing between organizing and elections but of using electoral power to make organizing easier, more effective, and more central to American life.

If the Left is serious about building lasting working-class political power, it must embrace a bolder strategy — rooted in economic populism, grounded in working-class communities, and committed to delivering the goods. That will require investing in a new generation of working-class leaders, engaging in year-round organizing in forgotten places, and advancing policies that match the scale of the wreckage left behind by neoliberalism.