Abraham Lincoln Knew Violence Must Be Addressed at the Root

Abraham Lincoln is often invoked in calls for civility and reconciliation across the partisan divide. But Lincoln himself understood that such reconciliation was impossible in his own time until justice had been served and slavery abolished.

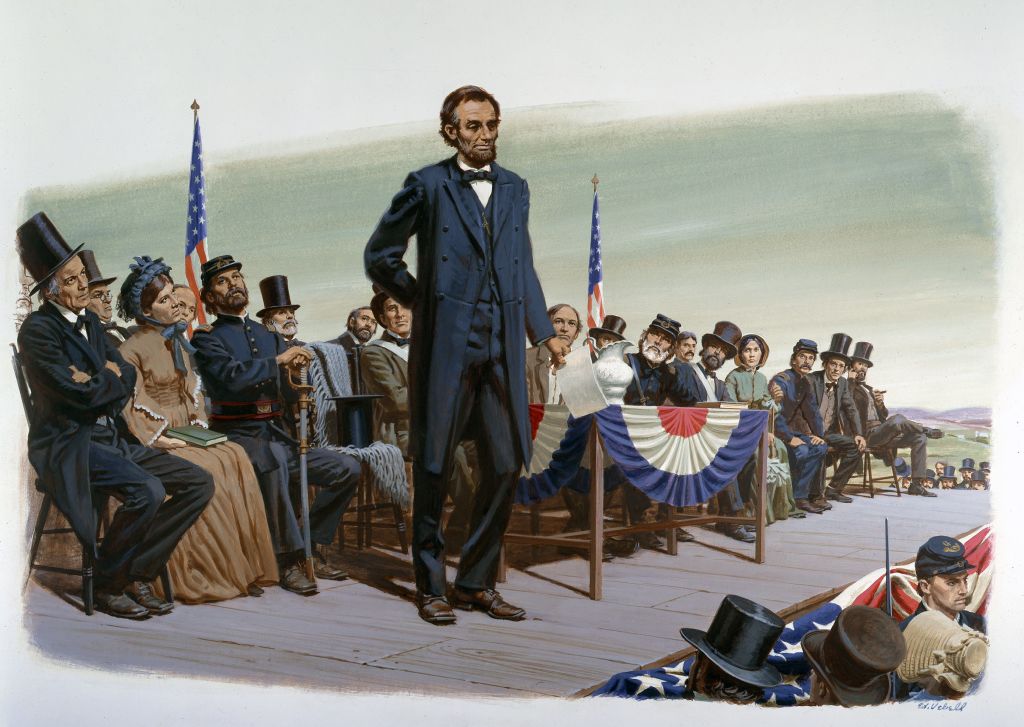

What made Abraham Lincoln great was that he understood that, in the end, there would be no establishment of the rule of law until justice had been served and slavery abolished. (Ed Vebell / Getty Images)

I understand the impulse, at moments like these, for politicians and public spokespersons to say that we need to talk across the divide, to acknowledge our similarities amid our differences, that we need leaders who understand there is no red America, no blue America, just America. It’s not my way of writing or speaking, but it runs deep in our political tradition. So it’s not surprising that people would turn to it.

Looking for precedents, people will often invoke Abraham Lincoln, particularly his first and second inaugural addresses (or least the conciliatory part of the second). The leader who bound up our wounds, who bore malice toward none and charity for all.

But Lincoln is an instructive case for a different reason. And that is that despite starting his career issuing bromides for peace and reconciliation, he came to understand, as time went on, a rather different alliance between words and deeds, toleration and power, reconciliation and reality.

From a young age — specifically, when he was twenty-eight years old, long before he came to national prominence — Lincoln had an uncanny sense that the growing violence of Jacksonian America was caught up with the question of slavery and abolition. In 1838, he delivered a fascinating address to the Young Men’s Lyceum in Springfield, Illinois, where he meditated on the growing predilection for violence, both political and apolitical, and offered cautionary words about where things were headed. Despite his keen understanding of the roots of the violence and its direction, the best counsel Lincoln could offer at this point was that all Americans needed to recommit themselves to the rule of law and the Constitution. Otherwise, he warned, some Napoleon Bonaparte type would come along and do one of two terrible things: free the enslaved or enslave the free. Despite his opposition to slavery, in other words, Lincoln’s recommendation at this point was for people to gird their loins of lawfulness against the truly violent: the abolitionists and enslavers. Both sides do it; we, in the middle, must not.

What made Lincoln great was not that early speech, though it’s interesting and prophetic in all sorts of ways that I can’t do justice to here. Nor was it his later giving into some bloodthirsty militarism during the Civil War, though there are moments of holy violence in his second inaugural that still send shivers up my spine and that I cannot read aloud without my throat seizing up and my voice cracking.

No, what made Lincoln great was that he understood that, in the end, there would be no establishment of the rule of law until justice had been served and slavery abolished. There could be no refusal of violence that would stick, that would be anything more than the blandest sanctimony, the emptiest piety, until the underlying social violence — the combination of the “Negro question” and the “labor question” — was resolved, through concerted action by the state.

What makes today’s calls for reconciliation and pleas for recognition of everyone’s humanity so formulaic, even feckless, is that they are severed from any sort of action or social awareness. At best, they rest on a studied inattention to the underlying social and economic roots of the problem. At this point, the politicians who speak this way sound like the very abolitionists who were rightly derided as crackpot utopians for their naive belief that moral suasion, without state action, could somehow win the day against slavery.

The difference is that those abolitionists had no power. Many of these politicians do.