Chicago vs. Trump’s Takeover

Chicago is attempting to model resistance to Donald Trump’s looming authoritarian military occupation of its streets.

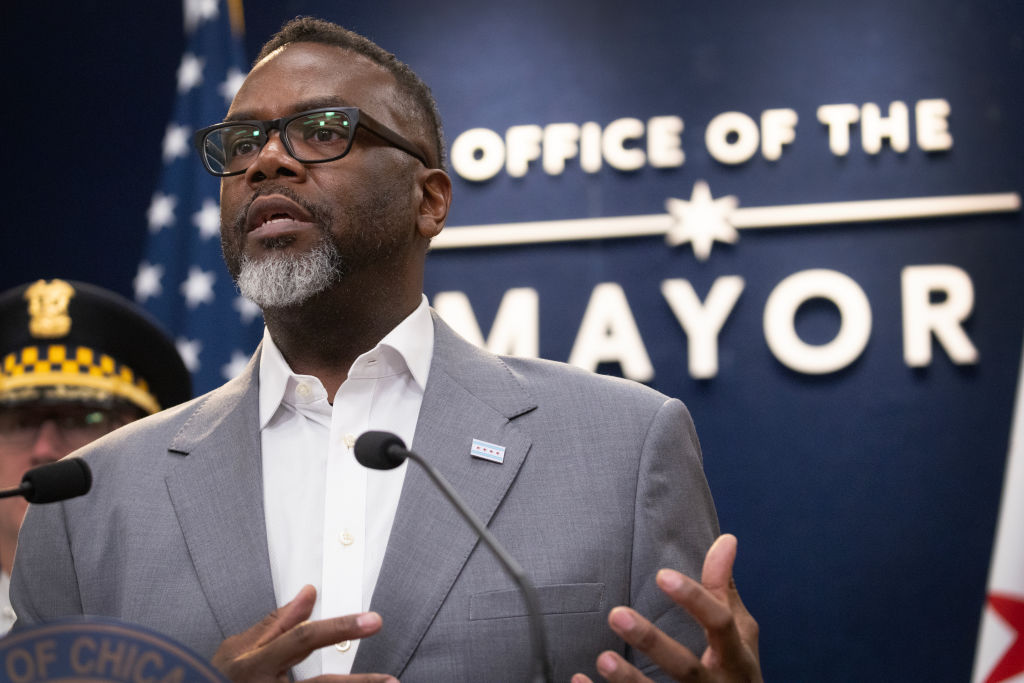

With Donald Trump's recent military ambitions in US cities, Chicago may be a model for municipalities looking to resist federal overreach from his administration. (Scott Olson / Getty Images)

What do you do when you’re mayor of a blue city and a far-right president sends the military to your streets? Right now, we’re seeing two very different answers.

In Washington, DC, Mayor Muriel Bowser has chosen capitulation: she’s made clear she “greatly appreciate[s]” Donald Trump’s military occupation of her city, gushed that it has lowered crime, and, with troops’ time in the city expiring, ordered the city to keep indefinitely cooperating with federal law enforcement “to the maximum extent allowable by law.” White House officials have praised her for “working with the administration behind the scenes,” dismissing her criticisms of the president’s actions as just “things she says in public.”

In Chicago, Mayor Brandon Johnson is choosing a different path: defiance. He has vowed to “defend our democracy” and “protect the humanity of every single person” in the city, attended a protest against the deployment, and pointed to the plunge in crime he has presided over — including a 32 percent drop in homicides and 21 percent drop in all violent crime. This past weekend, he issued an executive order pushing back against the impending deployment of federal agents and the National Guard to the city.

With Trump indicating his military ambitions are much bigger than the three cities he’s targeted so far, Chicago may be a model for municipalities looking to resist future federal overreach from his administration — or any future right-wing president’s.

Johnson’s August 30 order was signed on the mayor’s own initiative. But it’s also the culmination of an approach that has given working-class community groups a seat at the table and the ability to influence policy decisions under his administration.

“This has been building off of months of meetings,” says Cassio Mendoza, Johnson’s press secretary. “We’ve been meeting with these folks, they’ve been giving us feedback on what steps they would like to see the city take and working out what’s legally possible.”

“It has been a community-driven response to what we have identified as a threat to the texture of the city,” says Rich Wallace, founder and executive director of Equity and Transformation — a Chicago-based group focused on organizing black workers — who was at the press conference where Johnson announced the order.

Central to the order, for instance, is the Illinois TRUST Act, pushed by a coalition of activist groups and signed into law in 2017, which limits state and local law enforcement’s ability to assist federal authorities with immigration enforcement.

These efforts from city hall are being buttressed by the work of community groups organizing in concert with the mayor’s office to make sure Chicagoans likely to be targeted by federal forces have the resources they need. That means everything from having legal aid and rapid response teams in place to education campaigns to ensure Chicagoans know their rights and have their legal ducks in a row if they or a family member is detained. At times, that has meant being in touch with organizers in cities already overrun by a surge of federal agents to understand the tactics of the invading forces.

“We can’t prepare for everything, but we’re going to go into this moment to be as nimble as possible and be as flexible as possible,” says Brandon Lee of the Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights (ICIRR).

It also includes protest. The kind of muscle the city will be able to muster if and when federal agents and troops swarm Chicago’s streets was on display earlier that week on Labor Day, when thousands turned out to protest the planned deployment, and where organized labor — including the Service Employees International Union, United Auto Workers, and the Chicago Teachers Union, with its close relationship with Johnson — was well-represented.

One Eye on the Future

Johnson’s executive order is not the ceiling when it comes to activist demands. Earlier this week, veterans called on Democratic governor J. B. Pritzker to use his status as commander in chief of the Illinois National Guard to formally direct service members to refuse Trump’s order — provocative, no doubt, but also perhaps legally sound, given a federal judge this week ruled the Los Angeles deployment flatly illegal and suggested anything similar in Chicago would be, too.

“Certainly we’d like elected officials at all levels to take the necessary steps to protect people in the area,” says Lee. He says that in the coming month, a coalition that includes ICIRR will be putting together a slate of demands for state lawmakers, which, depending on what community members propose, could include such a measure — though Pritzker has steadfastly avoided commenting on the idea.

Meanwhile, the massive cost of putting troops on Chicago’s streets is feeding further resentment among those who take public safety seriously.

“There are a million other ways that money could be invested to make sure we’re safe. That’s the rallying cry of the community right now,” says Wallace.

Johnson ran and won on a progressive anti-crime platform that included investing in housing, mental health, and youth employment. The approach seems to have worked: this summer saw the fewest murders in Chicago in sixty years.

But that agenda has also stalled. A potentially transformative affordable housing measure, “Bring Chicago Home,” which would have raised $100 million per year for combating homelessness by raising the tax on large real estate sales failed a vote by referendum in 2024, partly thanks to real estate–backed fearmongering about its price tag.

Yet according to one estimate, Trump’s troop deployment in Chicago is set to cost just under $1.6 million per day, four times the daily cost of housing the city’s homeless. If troops stay in the city until the end of the year, as Trump is aiming to do in DC, that would mean a total cost of more than $180 million — a price tag that could nearly have paid for two years’ worth of the Bring Chicago Home initiative. Trump has also revoked billions of federal dollars meant for Chicago to fund schools, economic development, and gun violence prevention, raising further doubts as to how sincerely the troop deployment is motivated by fighting crime.

Both the mayor’s office and working-class community groups view the pushback to the federal deployment as part of a longer-term organizing effort against Trump’s authoritarianism — including fears that he will resort to the same tactic before future elections to suppress the vote. After all, thirteen of the twenty cities with the worst homicide rates are governed by Republicans, including the top four, yet Trump has shown no indication he plans to deploy troops there.

Johnson and other Illinois officials’ defiance of Trump is not out of step with public opinion in Chicago. A poll of city residents over June and July found that two-fifths disapprove of Trump’s handling of immigration enforcement, nearly half opposed helping Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and other federal agencies carry out deportations, and a majority favored “a national civic uprising against President Donald Trump’s agenda” — including large shares who were willing to support even violent resistance to Trump and his immigration agenda.

Outrage against Trump in his first term helped catalyze the passage of the same TRUST Act now being used by Johnson to put limits on federal forces, and which was signed into law by a Republican governor. Chicago organizers believe the White House’s overreach now may help coalesce a resistance movement that will last much longer than federal forces’ presence in the city.

“Trump’s tactics are meant to divide, to say this community is acting out of line, this community shouldn’t be here, to make us point fingers at one another,” says Lee. “But Trump right now is bringing people together, and that’s laying the groundwork for pushback to future attacks.”

Authoritarian power grabs have rarely been stopped through legalism and procedure. Eight months into Trump’s tenure, the courts have been an important check on the White House, but they have also had profound limits: partly because the Trump administration has shown a willingness to defy them, and partly because they have sided with the White House on a number of occasions. The Trump team has flirted with the idea of wholesale ignoring the courts, and it remains an open question how they would actually stop him if he decided to do so.

In other countries, such power grabs have been met with mass civil disobedience from a combination of protesters and workers. Last year’s attempted coup in South Korea was halted after only a few hours thanks to a swift mass uprising of thousands of people who effectively physically prevented the military from taking control of the country’s equivalent of Congress. In Bolivia, where the ruling party was deposed by a 2019 coup, continued, often disruptive mass mobilization by its supporters was essential to making the new regime back down and renew elections.

Similar lessons abound from the relatively recent overthrow of dictatorships in countries like Brazil and Chile. In all of these cases, the peaceful uprising of an overwhelming mass of civilians opposed to the regime viscerally displayed its lack of popular legitimacy, made it more likely for outnumbered and demoralized troops to choose not to fire or even to defect, and encouraged those who were silent or passively opposed to become more vocal.

A government whose existence rests on its ability to intimidate the public into compliance is often only checked by mass civil opposition, and Trump’s America — where the ruling regime acts in blatant disregard for the law, openly threatens its political opponents, and sends the military against its own citizens — is likely to be no different. There have been glimmers of this, in the surprisingly broad and deep mobilization of the “No Kings” protests, but it is still unclear if the burgeoning pro-democracy movement in the United States is able to conjure up the kind of coordinated mass unrest that challenged authoritarianism in these other countries.

Johnson’s executive order is narrow and largely symbolic; it’s unavoidable that municipal and even state governments simply do not have all that much power compared to the federal government. What may be its more important legacy is in using the power that state and local governments do have to lay the groundwork for and encourage the kind of civilian opposition needed to challenge a future, more concerted power grab. It’s a model that other Democratically governed areas may want to pay attention to, if they really want to create a robust, last line of defense against naked authoritarianism.