Tipped Workers Don’t Need Tax Relief. They Need Real Wages.

Donald Trump’s No Tax on Tips policy is a major part of his appeal to working-class Americans. But tipping is itself a strange and flawed system invented to preserve inequality. Critics worry Trump’s policy will only intensify tipping culture.

Americans think tipping culture has gone off the rails. Donald Trump wants to tinker around the edges of the system with tax cuts for tipped workers, but many argue that the whole system should be eliminated and replaced by full wages. (Jeffrey Greenberg / Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

“When I get to office, we are going to not charge taxes on tips, people making tips,” Donald Trump said at a June 2024 election rally in Las Vegas, home to tens of thousands of tipped workers. “You do a great job, you take care of people, and I think it’s going to be something that really is deserved,” he added. This pledge, which Trump would go on to repeat at multiple campaign events over the next few months, became a signature part of his appeal toward working-class Americans.

Just over a year after the Las Vegas rally, President Trump appeared to fulfill his campaign promise by securing passage of the No Tax on Tips policy as part of the sweeping legislative package known as the One Big Beautiful Bill. That wasn’t a hard task. The measure was popular in polling surveys and enjoyed the backing of lawmakers from both parties. No Tax on Tips seemed to have all the markings of a commonsense idea whose time had come.

But beneath the facade of this supposedly simple tax waiver for hardworking Americans lies the reality of a service industry powered by ever-rising worker insecurity. Dig even further and you discover the legacy of slavery and Jim Crow embedded in the practice of tipping, obscured by the passage of time, newer migration patterns, and increasingly high-tech forms of exchange.

Over the last few months, I have traveled across America talking to a wide array of tipped workers in an attempt to understand the shape-shifting phenomenon of tipping. I asked workers how it felt to have been at the center of a US presidential election campaign, and whether they think the No Tax on Tips will improve their lives, as has been repeatedly promised. But I also chose this as an opportunity to ask and understand: Why is tipping so rampant in the United States, and who does it benefit?

For thirteen long years Humberto, who prefers that I use only his first name, worked at a restaurant earning no wages whatsoever, making his living solely through tips. At the age of eighteen, he had moved from Mexico to America in search of brighter economic prospects. But being an undocumented immigrant without a college degree, Humberto had few options. He took the job he got: a server at a Mexican restaurant in Louisville, Kentucky. Each time he complained about the lack of formal wages, the restaurant’s owners would threaten to call Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) on him, potentially having him deported. And so Humberto stayed on even as he “felt like a slave,” he told me. Indeed, he was working in conditions similar to the black servers who were hired just after the abolition of slavery over a century ago.

For workers like Humberto, the No Tax on Tips policy does close to nothing. “I wasn’t even being paid the subminimum wage of $2.13 an hour that my employer owed me. And I was barely making enough tips to survive,” Humberto recalled. According to Yale University’s Budget Lab, over a third of tipped workers don’t make enough to pay federal income taxes. The No Tax on Tips law has zero effect on their financial situation.

For the remainder of tipped workers, the new law seeks to eliminate federal income taxes on tips. The policy has a cap of $25,000, and workers will have to pay taxes on tips on any amount they earn beyond that. The tax benefits wouldn’t apply to yearly incomes exceeding $150,000. Under the policy, which expires in December 2028, workers would still need to pay into Social Security and Medicare through payroll deductions.

In 2013, Humberto filed a case against the restaurant and won compensation in a court-approved settlement. He eventually became a legal resident, too. But the restaurant industry continues to flex its structural power over the most vulnerable members of its workforce. In Humberto’s view, No Tax on Tips is worse than a Band-Aid. Tipped workers, he says, should be earning “a stable living, not dependent on tips in the first place.” And second, he says, “It will also increase the tipping problem.”

Tipping is indeed a problem, not least for customers. One in three Americans thinks that tipping culture has “gotten out of control,” and nearly two-thirds have a negative perception of tipping. People are tipping less at restaurants than they have in at least six years, peeved over rising prices and increasing prompts for tips in unexpected places. With the digitization of tipping, ubiquitous screens stare the customer in the face, asking them if they want to pay 18, 20, or 25 percent of their bill as a tip to the server. Nearly three-quarters of Americans say they have seen an expansion of tipping expectations in recent years.

“I am the one standing in line for a cookie. All you are doing is handing it to me. I mean, I could have stretched my arm and taken it myself from across the counter. So what am I tipping you for?” said Chicago resident Judy Flock. “With the digital screens, and with the staff being able to see them directly, it’s just a lot of pressure.” Judy and her husband Frederick are from Germany and moved to America three years ago. “In Germany, tipping exists, but as a healthy practice. You tip where you want to, as a bonus. It’s not an unwritten rule,” said Frederick.

Meanwhile, tipped workers continue to suffer because of the instability and insecurity that comes with being dependent on tips to earn enough to make rent every month. The poverty rate of tipped workers is twice as high as that of the non-tipped workers.

Critics worry that the No Tax on Tips law will only exacerbate the pervasiveness of tipping. The policy restricts tax-free tips to workers who have “an occupation which customarily and regularly receives tips,” but does not specify which jobs, leaving it open to interpretation. Under present federal law, any employee can be considered a “tipped employee” if they customarily and regularly receive more than $30 a month in tips — a low bar for inclusion.

Under the new law, tips are exempt from taxes, but wages still aren’t. This incentivizes employers to find ways to make their workers’ jobs dependent on tips, essentially asking customers to subsidize their payrolls so employers can minimize tax expenses. The tax exemption makes it easier to sell workers on this arrangement.

Tip jars have already been spotted at odd places like the vet’s office, raising eyebrows. “The policy could result in more and more employers and businesses misclassifying the kind of work their workers do,” said Dustin Reinstedler, president of the Kentucky AFL-CIO. “Tomorrow, a contractor might tell a laborer he will be paid in tips, not wages. Tipping would become more and more widespread, not less.”

Economists insist that a better way to actually help tipped workers would be to raise their wages independent of tips. “Raising the wage is in contrast to No Tax on Tips, which is effectively a taxpayer-provided subsidy to employers disguised as a benefit to workers,” said Nina Mast, economic analyst at the Economic Policy Institute. “Raising the wage provides the greatest benefit to those who need it the most without letting employers off the hook.”

Tipping’s Roots in Slavery

Tipping was originally a phenomenon limited to the European aristocracy, where it was customary for masters to give servants extra money after a good performance. Some wealthy Americans traveling to feudal Europe were left impressed by this culture and tried to bring it back to the United States in the mid-nineteenth century, but the custom was frowned upon as elitist, crude, undemocratic, and “un-American.”

The end of slavery changed the social calculus. After emancipation in 1865, millions of newly freed black people entered the paid labor force. Black people could no longer be owned as slaves, but they weren’t being hired for the top jobs either. For black men, a major employer emerged in the form of Chicago’s Pullman Railroad Company, which hired them as porters.

Many black women found corresponding work as domestic workers, cooks, and cleaners. Eventually, they also began working in the restaurant industry, where they were paid a negligible salary, sometimes literally nothing. They were to earn what they could through tips, a reward for “good,” efficient, and deferential behavior. For many white employers, especially in the South, tipping was a way to keep black workers in a servant’s role while also keeping wages low. It was a strategy for keeping the racial order intact and satisfying employers’ demand for low-cost labor.

Employers increasingly found this arrangement satisfactory, not least because they discovered they could get the customer to subsidize low wages. It soon began to include all workers in public-facing industries like restaurants, including white workers.

In his book Tipping: An American Social History of Gratuities, cultural historian Kerry Segrave quotes a journalist writing in 1902 about his experience of tipping at restaurants:

I had never known any but negro servants. Negroes take tips, of course; one expects that of them — it is a token of their inferiority. But to give money to a white man was embarrassing to me. I felt defiled by his debasement and servility. Indeed, I do not now comprehend how any native-born American could consent to take a tip. Tips go with servility, and no man who is a voter in this country by birthright is in the least justified in being in service.

There was initially some pushback against the growing tipping culture, with six US states banning the practice and making it illegal not just to tip, but also to accept the tips.

“In an aristocracy a waiter may accept a tip and be servile without violating the ideals of the system. In the American democracy to be servile is incompatible with citizenship,” wrote activist William R. Scott in 1916 in his book The Itching Palm. “Every tip given in the United States is a blow at our experiment in democracy.”

In time, the practice became too commonplace for any law to hold water. By the late 1920s, all anti-tipping laws had been repealed.

But workers had an outstanding problem: replacing decent wages with tips created severe worker insecurity. In 1925, civil rights activist A. Philip Randolph organized black Pullman Railroad Company workers into the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first labor union for African American workers in a white-owned business. A union pamphlet from the period sharply explained the function of tipping:

The tipping system has been utilized time and again to hinder the porters from obtaining improved working conditions . . . The Company is able to avoid responsibility for the bad working conditions — the long working month, insufficient rest, long runs, etc. — by always using the argument that “porters wish to follow tips to their destination,” and so would not welcome shorter hours of labor. The Company also makes further savings by basing all its insurance and pension payments upon the wage rates of the Company rather than upon the total income of the porter.

After a twelve-year-long fight, the Pullman Porters, as they were called, negotiated a contract and won better wages in 1937, thus minimizing their dependence on tips. Tipped restaurant workers were not as lucky. Alongside predominantly black agricultural and domestic workers, they were excluded from key New Deal labor reforms. That meant they were ineligible for a minimum wage and Social Security — and highly beholden to the vagaries of the tipping system.

In the 1960s, the Civil Rights Movement — under the partial leadership, not coincidentally, of A. Philip Randolph — demanded that the minimum wage be extended to all workers. In 1966, congress ceded some ground, but with a catch. Instead of including restaurant workers in the list of those who would earn a minimum wage, they introduced a new category: the “subminimum wage.” If the tips didn’t cover the difference between the “sub” and the “minimum,” the employer was supposed to make up for it.

The federal subminimum wage, which started at a few cents, was last increased to $2.13 in 1991 and has remained frozen for more than three decades.

Many states have increased the subminimum wage on a state level, but seven of the ten states with the highest percentage of African Americans are stalled out at the federal subminimum wage of $2.13. Notably, all of these seven states are former slave states.

The State of the Subminimum Wage

According to The Budget Lab, there are four million tipped employees in the United States. At least 1.3 million of those are paid the federal subminimum wage of $2.13 per hour. Another 1.8 million tipped workers receive wages above $2.13, but still less than their state’s minimum wage.

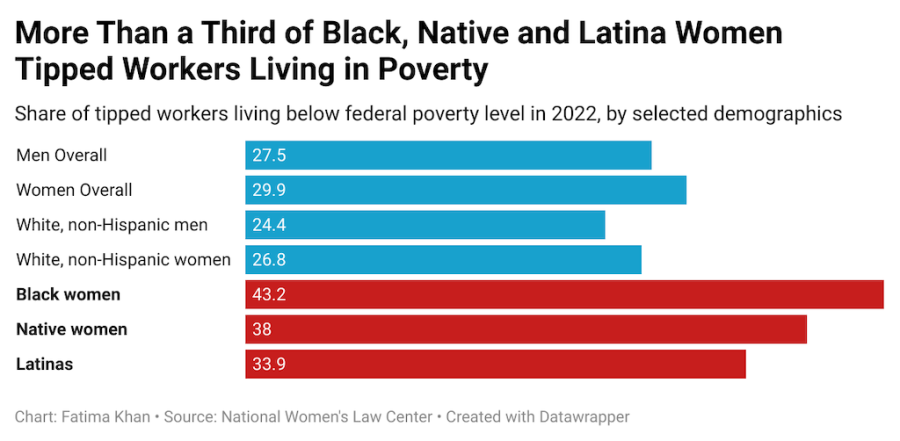

Women make nearly 70 percent of all tipped employees, and women of color are among those most heavily affected by the subminimum wage. Black, Native American, and Latina women who work for tips are disproportionately likely to live in poverty.

While workers from different industries, such as manicurists and cab drivers, can qualify as tipped workers, more than 60 percent of all tipped workers are employed in the food service industry.

Tipping is part of a greater phenomenon that political scientist Jacob Hacker has called “the Great Risk Shift,” whereby our society increasingly shifts the economic burden from the government and private employers onto individual workers.

The spread of tipping “is absolutely part of the Great Risk Shift,” Hacker said, and is a consequence of employers wanting to “transform business uncertainty into worker insecurity. But we shouldn’t have any illusion about who wins from these arrangements: employers that don’t have to pay their workers a living wage.”

No Tax on Tips intensifies the Great Risk Shift, while at the same time cynically making tipped income seem more lucrative for workers. For all the populist vocabulary of No Tax on Tips, it entrenches a system that eases the burden of financial risk off the backs of corporations and onto the shoulders of their insecure tipped workers.

Legally, employers are supposed to cover the difference between whatever is earned in tips and the minimum wage, but that is often not the case, resulting in tens of thousands of wage theft cases, like Humberto’s. In many other cases, not only is the difference not covered, but tips are found diverted from the workers’ income to the managers’, which also technically constitutes wage theft.

As of 2025, there are only seven states and a handful of cities that mandate that all tipped workers, regardless of how much they earn in tips, must be paid the full state minimum wage. In every other state, tipped employees are effectively dependent on the generosity of strangers to meet a minimum wage. According to the Department of Labor, nineteen states continue to follow the federal subminimum wage of $2.13 for tipped employees, while the remaining states have it only marginally higher. This means that depending on where you are in America, a 20 percent tip at your local diner will have a demonstrably different impact on the worker you’re tipping.

To study this difference, and to contrast how this dependency could manifest in the lives of tipped employees, I traveled to Chicago, Illinois and Louisville, Kentucky. The two states share a border and are separated by an informal extension of the Mason-Dixon line separating the slave South and the free North. Louisville maintains the subminimum wage of $2.13 while Chicago passed legislation phasing it out and moving towards paying restaurant workers a full minimum wage.

How Race and Tips Interact

Louisville is among the most racially segregated cities in the United States, partitioned by a line colloquially called the Ninth Street Divide, separating the city into black and white residential areas.

Alicia Michelle Wilson, 60, has been working at the diner chain Bob Evans for over sixteen years. Wilson initially started off as a cook, but after a falling-out with a fellow chef, she decided to try her hand at the front of the house as a server. Her salary immediately fell from $18 an hour as a cook to $2.13 as a server. “The expectation was that tips will help me power through,” she said. And they did, for a while. Soon, older clientele stopped dining out during the Covid-19 pandemic. They never really came back in full force, and now she doesn’t make more than $150 with tips at the end of a seven-hour shift.

The majority of the customers in Wilson’s restaurant are white, and she is one of the only two black servers. In her time at Bob Evans, she has had multiple experiences with overt racism. “One time, two white men came and explicitly said, ‘We don’t want her, we don’t want that skin color.’ It was humiliating,” she recalled.

More recently, a group of twelve came to the restaurant on Christmas Eve. Wilson sat them down, after which they asked, “Don’t you have someone else working today?” Her white colleague Natalie then took over, and they told her that they were glad to have her as their server. They left Natalie a $220 tip that night, Wilson noticed. “The funny thing is that they can’t see that the cook making all their food inside the restaurant is also black,” she said with a chuckle.

White customers aren’t the only problem. George Zakaria, 22, has been working at the upscale Bob’s Steak and Chop House in Downtown Louisville for four years. Despite starting on the $2.13 base pay, he was excited to earn whatever he could to support his mother, who had moved from South Sudan to Kentucky with her seven children over a decade ago. But Zakaria’s hopes were soon squashed by the reality of tipped work in the restaurant industry.

Once Zakaria interacted with a customer, a black woman, who was curious about his background. “Oh you don’t look like a George,” she told him. “When I was in Africa a week ago, all the names were like tut tut tut.” The clicking sound she made — “tut tut tut” — was a reference to some African languages and names featuring what are called click consonants. A recent TikTok trend showed children in African countries saying their names, with the clicking sound being a source of awe and bemusement for viewers.

According to a study by affiliates of Cornell University and Mississippi College, the server’s race can often determine how much customers tip. The study, conducted at a Mississippi outlet of a national restaurant chain, found that black servers were consistently tipped less than the white servers — not just by white customers, but across the board, including by black customers. Michael Lynn, the study’s author and a tipping expert of three decades, has conducted multiple such studies in different parts of the United States, including the North, indicating that race is a major factor in tipping. The authors of the Mississippi study term this the “server race effect,” and argue that it’s impacted less by overt racism like Wilson experienced than by implicit racial attitudes. “Customers won’t say they are deliberately tipping the black servers less, but instead attribute it to poor service quality,” said Lynn. “They might not even be aware of their biases.”

Similar studies have been conducted for other tipped employees, too, and show similar results. A study about taxicab drivers found that black drivers were tipped, on average, approximately one-third less than white cab drivers.

As a young black man with dreadlocks, Zakaria feels he has to be conscious of how he presents himself. “They stereotype black people with dreads. I know I just have to be on my toes, be super vivacious and friendly or I could easily be perceived as aggressive. It’s just something I need to do to compensate for being black, or my tips will suffer,” he said.

Despite working at a fine-dining restaurant and earning more in tips than his peers in average diners would, Zakaria plans on leaving the industry soon. “The thing that really pisses me off here is the way people just wave at you and expect you to drop everything and show up,” he said. “That weird hand motion thing they do, like I am not a person. Just talk to me, I will get you whatever you need. But don’t be commanding me like a dog. People forget you are human. They think because they are tipping you, they own you.”

Both Wilson and Zakaria have seen headlines about the tax bill, but neither understands what will tangibly change in their working conditions. Not only are the two workers unaffected by the economics of the bill, but it also won’t come anywhere close to changing the day-to-day reality of their jobs, from dealing with explicit prejudices like racism to feeling generally dehumanized.

“I think they have achieved exactly what they intended to, which is to create confusion among tipped workers about what they are getting at the end of the day,” said Reinstedler of the Kentucky AFL-CIO.

Who Might Benefit From Trump’s Policy, and at What Cost

Tipped employees often describe “putting on a show” as an element of their job. Nowhere is this requirement more evident than at Hooters.

A “Hooters girl” typically wears the classic brand uniform: a tight white crop top accentuating her chest paired with short orange shorts. The Hooters girl, as per the company’s website, “is the icon of the Hooters Brand and has drawn guests into Hooters Restaurants for decades.” She must be “approachable, upbeat, and attentive to the needs of the guests as she socially engages with and entertains each individual guest.”

What the job posting doesn’t mention is that the Hooters girl is paid a subminimum wage, which in Louisville is $2.13.

Alyssa Liang, 28, has been a Hooters girl for six years, and her pay is now a few cents more — $2.18. She doesn’t even describe herself as a server at all. “We are not hired as servers, we are hired to be entertainers. So we are held at a higher standard for things like our looks. One of our rules is that you cannot come into work without having at least three pieces of makeup on,” Liang said.

Liang acknowledges the hyper-sexualization implied by the mandatory dress code. Her Chinese-Japanese and Korean heritage adds another layer. Customers don’t expect to see an Asian woman behind the bar, she told me, and they definitely don’t expect her to have this accent of a “true Kentuckian.” “It throws them off, so I get racist remarks from them, like they will ask me in disbelief, ‘Are you from here? Really? Where did you get this accent from?’ I mostly laugh it off,” she said.

Liang is the only Asian woman working at her branch of Hooters. “I don’t like to think of myself as that, but I know as an Asian girl, I am a fetish.”

As a Hooters girl, her presence is the brand’s unique selling proposition — many men come into the restaurant just to interact with her and her peers. Sexual harassment and creepy behavior are always a distinct possibility. Once, a man asked Liang her shoe size after remarking that her feet looked tiny. She answered that she was size five, and he asked to see her feet. “I played along, but then he said he has never been with a girl with feet size five, and he would like to buy my socks,” Liang recalled. She laughed and politely declined the request.

It is often customers like these who determine how much the Hooters girls get to take home. Despite Liang’s rejection, this customer left a really good tip. “He tipped me well because he knew that was an awkward question for him to ask, and an awkward situation to put me into. So he had to compensate for that,” said Liang. This is a fairly common phenomenon among the Hooters’ clientele. “Most men are embarrassed to come here, so they tend to tip well because they don’t want to feel like they exploited you. Even though they didn’t. But they have a guilt that they want to assuage. Hooters is a weird place like that,” she said.

According to a study, waitresses with large breasts, blonde hair, or slender bodies receive larger average tips than their counterparts without these characteristics.

Liang has been a Hooters girl since she was in nursing school in her early twenties. Now she manages this job alongside work as a jail nurse. Despite the challenges at work and outsiders’ sometimes critical perception, Liang loves this job. Rocky encounters notwithstanding, Liang has sometimes had such great days with tips that she would rather “risk it” by continuing to earn a subminimum wage than have a full wage with potentially lower tips.

One time, when UFC champion Conor McGregor’s fight was on, she told her customers she was willing to bet all her tips if he lost. He won, and her tips were all doubled. She walked away with $800 in cash that night. “It was a gamble, I could have lost too,” she said. “But it was unlikely the men would ever take away all my tips. They are not jerks. So it was going to be a win-win.”

One critique of the bill concerns the differences in experiences between Wilson and Zakaria on the one hand and Liang on the other. Observers point out that high-earning tipped workers at outlandish spots like Hooters, or even at garden-variety fine-dining restaurants, will end up getting a tax break while low-wage tipped workers won’t.

Moreover, back-of-house workers at restaurants, who aren’t technically tipped workers, won’t get any respite whatsoever. “Tipped workers like dealers in Las Vegas earning six figures will get the break, but food prep workers earning minimum wage in the same casino will not,” said Sylvia A. Allegretto, Senior Economist at the Center for Economic and Policy Research.

Banning Tips, Paying Full Wages

In October 2023, Chicago’s city council passed the One Fair Wage ordinance, making it the biggest city to do away with the subminimum wage for tipped workers independent of state law. The ordinance stated that the subminimum wage will first be increased from $9.48/hour (the subminimum wage in the city at the time) to $11.02/hour, and then gradually be phased out by 2028. After that, it will be pegged to minimum wage in the city. As of now, the minimum wage in Chicago is $16.60/hour, which many restaurants have already begun paying since the ordinance passed.

Some restaurants have found ways to not only pay their workers a full wage, but also ban tips. And despite the industry’s claims that replacing tipped work with decent wages will put them out of business, these restaurants have managed to keep their doors open and even thrive.

Among them is Chicago’s Thattu, a restaurant known for its exquisite South Indian cuisine, which was included in the New York Times’ list of the fifty best restaurants in the United States in 2023. Owners Vinod Kalathil and Margaret Pak, a husband-and-wife duo, had worked in finance for several years before deciding to start a pop-up food stall in 2019, which turned out to be a huge success. But one thing stuck out like a sore thumb to them. “We were using a phone with a small screen on it for tipping. We would see customers literally take the phone away from us and hide the screen while entering the tip amount, because they didn’t like the pressure of us looking at them. The whole thing just seemed too confrontational, the opposite of what hospitality is supposed to be,” said Kalathil.

So when the couple built their full-fledged restaurant in 2023, they made a dramatic decision: no tips. A large red board greets the customers when they enter Thattu, saying “No Tips! No Service Charges!”

Kalathil and Pak said that while they wanted to prioritize the customer experience, they also wanted to create a safe space for their employees. “Dependence on tipping would go against that as they would feel obliged to put up with things they don’t want to,” said Kalathil.

To compensate for lost tips, Thattu’s policy is that a minimum of 8 percent of the sale revenue goes to all the employees, including the back-of-house workers. The more the restaurant sells in a week, the more workers earn, over and above their base salary of $19 per hour. “The employees we attract are those who are looking for something steady. They could work at restaurants where they earn a lot more in tips. But here they can be sure to walk home with a stable income,” said Kalathil.

A study of the restaurant industry conducted in 2013 found that restaurants that offer high relative compensation and job security have significantly lower turnover rates, resulting in higher productivity for the restaurant. It also found that restaurants can cut their employee turnover almost in half by increasing wages.

Thattu became “very profitable” in its first year, all the while paying the workers well over the minimum wage, let alone the subminimum wage. That doesn’t mean business hasn’t been totally smooth. “We are at a great disadvantage compared to other restaurants because we are paying high payroll taxes. The taxation system is built in such a way that it incentivizes restaurants to encourage tipping,” said Kalathil.

The Chicago ordinance began implementation in July 2024, and the 2025 employment data isn’t yet available. But in Washington, DC, a similar ordinance phasing out the subminimum wage for tipped employees was implemented in May 2023 — and has not had the apocalyptic effect restaurant industry lobbyists have warned about. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics data, employment has in fact risen in DC’s leisure and hospitality industry, from 70,235 in January 2023, before the policy, to 73,257 in January 2024, nine months into the policy. Last month, despite those figures, the DC city council modified the ballot initiative that would’ve led to the end of the subminimum wage by 2027.

This is the second time since 2018 that the DC city council overturned voter-supported moves that would’ve raised tipped workers’ base pay until it reached the regular minimum wage. While the council cited financial struggles faced by the restaurant industry as the reason, there is no evidence that the policy is causing harm to businesses. Saru Jayaraman, who founded the organization One Fair Wage, which has long advocated for the end of the subminimum wage for tipped workers, denounced the council’s move, saying, “This isn’t just a rollback of wages. It’s a rollback of democracy. Voters spoke loudly and clearly, twice, but instead of honoring the will of the people, councilmembers sided with a corporate lobby that spreads lies and bankrolls influence.”

Moreover, studies conducted in other countries gauging the employment effects of minimum wage, such as in Germany, found that bringing in a nationwide mandatory minimum wage did not lead to unemployment. This information has long been known: in the 1990s, a famous study showed that when New Jersey increased its minimum wage, it did not incur job losses compared to its neighbor Pennsylvania, which stuck to a lower wage.

Restaurants like Thattu are at the spearhead of a protracted battle. Campaigners with the organization One Fair Wage hope that as experiments like Chicago’s grow into credible examples and as more restaurants adopt the full-service wage model, a snowball effect will make the tipping system increasingly unviable.

Medicaid and SNAP Cuts Could Hurt Tipped Workers

In early 2024, Gina, a tipped worker in Chicago, began feeling extreme pain in her left shoulder. On one palm held outward, she would carry heavy trays in and out of the kitchen, navigating through crowds, innumerable times in a day. Despite going to urgent care and later to hospitals multiple times, her pain was consistently dismissed. “I got the sense they were saying that holding plates all day is not like jumping into the fire to save someone’s life, so it’s all probably in my head,” she said.

Finally, one day at work, Gina couldn’t physically lift her arm anymore. Her coworkers rushed her to the emergency room, where she was finally diagnosed with a cartilage tear, a tendon tear, and an impingement in her nerves going from her collarbone to her shoulders. But she was holding two restaurant jobs at a time — in an effort to secure tips from multiple shifts — which meant that she was considered part-time at both those jobs. Thus, she did not qualify for health insurance, for which full-time employment is a requirement. The majority of servers work part-time and lose out on important benefits.

Gina started a GoFundMe and was able to raise enough money from friends and family to get her surgery done. After the surgery, she couldn’t afford to take a long break. When she returned to work with her still-healing arm in a sling, her tips suffered due to slowed-down service. While she has always missed the cutoff for Medicaid by a few dollars, she has relied extensively on the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). “People assume that just because we work at restaurants, we have access to free food, which is often not true. Cutting down on Medicaid and SNAP directly hurts tipped workers. If we aren’t healthy, we can’t go to our jobs and earn. A tax cut won’t help as much then,” she said.

Tipped workers across the aisle rely heavily on Medicaid, which is seeing heavy cuts as part of Trump’s tax bill. While No Tax on Tips was a very popular campaign promise, later even emulated by Kamala Harris in her own campaign, experts say it needs to be seen in the context of the larger proposals in the One Big Beautiful Bill, which slashes benefits many tipped workers rely on.

Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY), who has herself previously worked for tips in the service industry, has slammed the bill. “The cap on that [bill] is $25,000 while you’re jacking up taxes on people who make less than $50,000 across the United States, while taking away their SNAP program, while taking away their Medicaid, while kicking them off of the Affordable Care Act,” she said. Calling the bill a “deal with the devil,” Ocasio-Cortez posed the question directly to tipped workers, asking,, “Is that worth it to you, losing all your health care, not being able to feed your babies, not being able to put a diaper on their bottom? In exchange for what?”

According to a report by One Fair Wage, as many as 1.2 million restaurant and tipped workers could lose access to Medicaid as a result of Trump’s benefits cuts. The group also estimates that only approximately 1.17 million workers would see a tax break with the No Tax on Tips law. This means that fifty thousand fewer workers would benefit from the law than those who would lose Medicaid.

Viewed in this light, the No Tax on Tips policy, which many tipped workers won’t even qualify for, is clearly a “look here, not there” distraction from the fact that essential supports for tipped workers are being dismantled as part of the same bill.

Biggest Champion of No Tax on Tips: The Other NRA

Among the first to celebrate the No Tax on Tips bill was the National Restaurant Association (NRA), the nation’s largest lobbying group for restaurant owners. “These measures are crucial for helping businesses have the working capital they need to cover payroll, manage rising supply costs, and stay competitive,” the association said.

Similar arguments have been made about labor costs by the Association for years now. When Herman Cain was President of the NRA, he argued that raising the wage for tipped workers would be detrimental to the growth of businesses. “When you make it more expensive to hire people who lack basic work skills and experience, you risk shutting them out of the workforce,” he said.

As a result of that 1996 Congressional hearing, the NRA reached a bargain with lawmakers: while the minimum wage can increase with time, that doesn’t automatically imply the “subminimum wage” will also increase. This decoupling from the regular minimum wage is why the tipped wage remained at $2.13 even as the minimum wage was gradually increased. The federal minimum wage, too, hasn’t increased from $7.25 since 2009 — but even when the minimum wage increases, it will stand decoupled from the subminimum wage.

“On one side, we have a lobby of national restaurant chains, and on the other we have among the lowest-paid workers in America. This explains why the subminimum wage hasn’t increased in over thirty years,” said Saru Jayaraman of One Fair Wage.

In 2021, an opportunity arose to end the subminimum wage at the federal level while also raising the minimum wage from $7.25 to $15. Former President Joe Biden’s $1.9 trillion Covid relief package included a monumental benefit for workers: the Raise the Wage Act. While the House passed the entire relief package, the Senate subsequently stripped it of the Raise the Wage Act.

After that, a group of progressive senators led by Bernie Sanders forced a vote on the wage change portion of the legislation anyway. This went on to become the longest open vote in modern senate history, beating out a 2019 vote on an amendment to prohibit President Trump from attacking Iran without authorization.

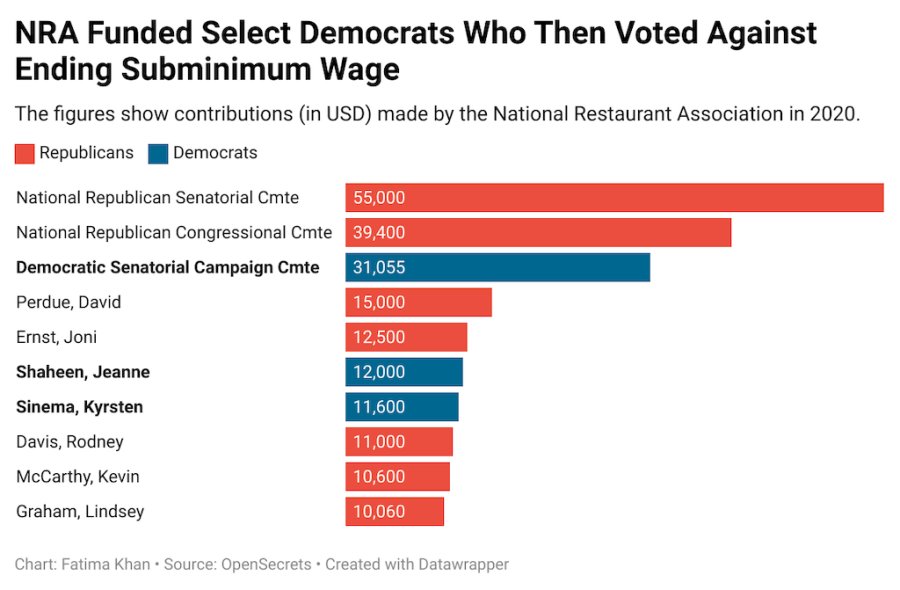

In the end, eight democrats joined the fifty Republicans in the Senate to vote against the act. The effort had been successfully crushed by the National Restaurant Association — frequently referred to as “the other NRA” in reference to the unrelated lobbying group the National Rifle Association. Democrat Senators Joe Manchin of West Virginia, Jon Tester of Montana, Jeanne Shaheen and Maggie Hassan of New Hampshire, Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona, as well as longtime Biden allies Chris Coons and Tom Carper all voted against the bill. Angus King (I-Maine), who caucuses with the Democrats, also voted against it.

The NRA spent $2.6 million on lobbying in 2020 to fight unfavorable legislation, including the Raise the Wage Act. A look into the NRA’s funding reveals that at least two of the eight Democrats who opposed the bill received funding from the NRA for lobbying purposes. Jeanne Shaheen and Kyrsten Sinema received funding from the NRA in 2020, just months before the bill went to the floor in 2021. Republicans have received the lion’s share of NRA donations for years, but the NRA also funded the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee in 2020, records show. Moreover, the NRA’s top lobbyist and executive vice president, Sean Kennedy, has also personally donated to Sinema and Hassan on a consistent basis.

A month after two of the Democrats, Sinema and Manchin, voted to kill the wage bill, they were added to the NRA’s annual national conference as keynote speakers. A poll in Arizona, Sinema’s home state, conducted in the same year she rejected the bill (2021) found that 72 percent of the state’s Democrats support raising the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour.

Soon after Sinema voted to reject the bill, the US Chamber of Commerce — the biggest corporate lobbying group in the country, which also opposed the Raise the Wage Act — awarded her with its Abraham Lincoln Leadership for America Award as well as its Jefferson-Hamilton Award for Bipartisanship. Sinema’s senate office noted in a press release that she “was the only Democrat to win both awards.” The Chamber also gave $17,000 worth of contributions to the two senators: Sinema and Manchin.

Two years after the Raise the Wage Act crashed and burned, the Chicago city council’s One Fair Wage ordinance passed with a vote of 36–10, a landslide victory for the movement to end the subminimum wage.

Jessie Fuentes, Chicago alderperson who sponsored the One Fair Wage bill, said that she and other members of the city council’s progressive caucus had refused to take any funding from the Illinois Restaurant Association. “I was never responsible to respond to them about anything, because neither I nor many of my colleagues ever accepted any money from them,” Fuentes said.

When Biden first announced that raising the wage would be part of this 2021 relief package, the NRA put out a statement criticizing it for posing “an impossible challenge for the restaurant industry.” It warned that restaurants would “respond by laying off even more workers or closing their doors for good. . . . A nationwide increase in the minimum wage will create insurmountable costs for many operators.” The Raise the Wage Act is currently stalled out in Congress, but these arguments from the restaurant industry persist.

“If your business model is to not pay people a living wage, then your business model is broken,” said Fuentes, in response. Fuentes, a Democratic Party member, criticized the party leadership for failing to put up an adequate fight for the working class. “After Trump’s victory, the biggest discussion that we find ourselves in is folks needing to know, who has their financial and economic interests at heart? What we watched in this past election was that Democrats did not say a word to articulate these economic plans,” said Fuentes. “We did not have families who were inspired enough by the Democratic Party. The Party needs to think about that.”

For their part, tipped servers are tired of the restaurant industry’s pleas of poverty and the endless excuses for inadequate wages — chiefly, complaints that labor costs are high enough as is.

“Restaurants cannot run without the labor,” said Morgan Hindman, a server in Chicago. “If you want to replace us with kiosks, go ahead, your entire business will shut down. Instead, if you really say labor is your biggest cost, then invest in actually taking care of us.”