How the Pharma Industry Botched Alzheimer’s Treatment

Journalist Charles Piller has exposed a pattern of shoddy and even fraudulent practices in Alzheimer’s research. It shows the drug research system needs serious reform, but health secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr is engaged in reckless vandalism instead.

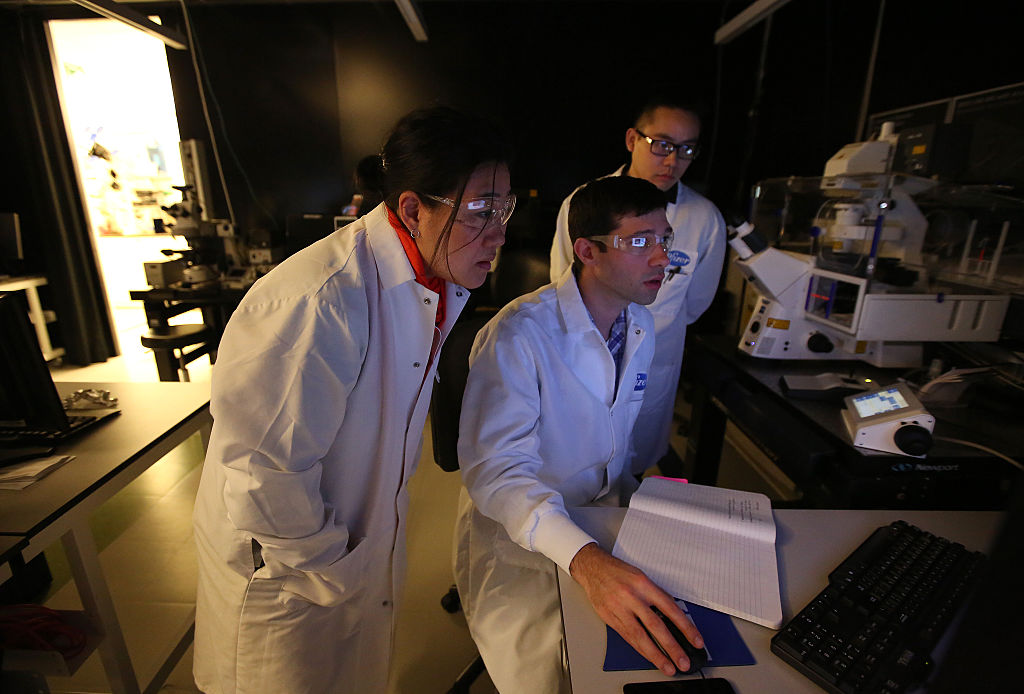

According to a new book, some of the scientific findings associated with Alzheimer’s research have come under suspicion, and scientists have been found falsifying their lab studies by doctoring the images used to demonstrate the data. (Pat Greenhouse / Boston Globe via Getty Images)

There is a terrible irony in the cuts that the White House has been imposing on the US medical research system, especially the funding of research centers into Alzheimer’s disease, which are reported to be facing a funding gap of $65 million. The irony begins in the fact that decades of research have failed to discover the causes of the disease or to come up with a cure. But it goes much deeper than that.

According to a new book by the science journalist Charles Piller, Doctored: Fraud, Arrogance, and Tragedy in the Quest to Cure Alzheimer’s, some of the scientific findings associated with this research have come under suspicion, and scientists have been found falsifying their lab studies by doctoring the images used to demonstrate the data.

Not, however, that this has anything to do with the current suspension of funding by the Trump administration. Although Donald Trump’s Health and Human Services secretary, Robert F. Kennedy Jr, referred in passing to “fraudulent” Alzheimer’s research during his confirmation hearing, he is not trying to reform a flawed research system. The funding cuts are just part of a wider campaign of vandalism that Kennedy has launched with the president’s blessing.

Time Bomb

Government funding of dementia research goes back to 1974, when the United States set up the National Institute of Aging (NIA). The move came in response to evidence emerging from biomedical science that the condition Alois Alzheimer discovered in 1906 was not just a liability of old age but a disease of the brain and that its incidence increased as the population aged.

In the US and elsewhere, there was talk of an epidemic, “a ticking time bomb,” and looming concern about skyrocketing medical and social costs. What emerged was a network that drew in government, hospitals, universities, Big Pharma, and civil society organizations like the Alzheimer’s Association.

According to the medical anthropologist Margaret Lock in her 2013 book, The Alzheimer Conundrum, this amounted to a marketplace in research, diagnosis, and treatment in which everyone was competing for funds. The figures bandied about, Lock says, were “designed to incite political action and increase funding for AD research.” That doesn’t mean they were exaggerated but rather that, as the lingo has it, their presentation was massaged.

The symptoms of dementia are now well known, partly through their representation in a steady stream of films and television programs, both fictional and documentary, over the last thirty years. These cultural products do not inform viewers about the wider context — they focus on the individual, their loss of memory and selfhood, and their relationship to their principal caregiver, frequently their spouse.

They are held together by bonds of love that are severely tested as the disease progresses, and it always ends up the same way — there are no happy endings, although some films opt for escapism. Alternatively the family may be dysfunctional, or the setting may be a care home, and the film may take the form of a drama, a black comedy, a thriller, a road movie, or whatever, because that’s the way film genres work.

Some hew close to the clinical manifestations of the disease, and some are extremely insightful. However, there’s an elephant in the room (what theorists call a structuring absence): there is never anything in them about the political economy behind the medicalization of the disease.

Biomarkers

Everyone agrees that dementia is in some way intimately linked to changes taking place in the brain marked by the rogue proteins that Alzheimer discovered, which are called biomarkers. These consist of plaques of amyloid and tangles of tau (discovered later) that impair brain signaling and destroy neurons.

Yet the more research was conducted, the more uncertainties and anomalies began to appear. Cases accumulated where brain autopsies showed biomarkers in people who had displayed no symptoms. There were studies of twins, whose genes were identical, one of whom developed dementia while the other did not. This raised critical questions about what stops someone who appears to be predisposed to dementia from contracting the disease — questions that remain unresolved.

As research intensified, scientists distinguished other varieties of dementia, discovered further biomarkers, and posed new questions. While dementia generally strikes in old age, a small number of cases, known as early onset, occur in middle age, occasionally even earlier.

Research in epigenetics, which investigates the way that gene expression is switched on and off, turned up a link with certain genetic mutations. But no one could work out exactly how they functioned. It also emerged that the disease has a long period of gestation, ten or fifteen years, before it begins to manifest itself.

Meanwhile, Big Pharma was at work, searching for drugs to alleviate the symptoms. According to one of the laboratory scientists working in the field, Karl Herrup, in his book How Not to Study a Disease (2021), they became fixated on a phenomenon referred to as the “amyloid cascade.”

The amyloid hypothesis suggested that these proteins resulted in a cascade of biochemical changes that caused dementia, and this became the main line of investigation for researchers. Despite the uncertainty of this hypothesis, researchers ignored emerging evidence of other factors, such as various possible forms of brain inflammation.

This fixation, according to Herrup, amounted to a simple dogma: “If you’re not studying amyloid, you’re not studying Alzheimer’s.” He argues that it was companies that dictated this approach rather than the science. Scientists needed those companies to bring the discoveries of laboratory research through the required program of trials by drawing heavily on government grants.

Depersonalization

Medical companies all competed against each other to find the killer drug. This was in spite of the fact that fewer than one in ten candidates that started phase-one trials in the US were successful in completing phase three and receiving official approval. Even among those drugs that did make it that far, approval might not be forthcoming in other jurisdictions.

There is now an established pattern. One after another, drugs are introduced that are at best only minimally effective over a limited period of time, if the effects are even noticeable. They are often withdrawn after a “futility analysis.” They don’t work at all with some people and are liable to produce a range of adverse physical side effects in others.

The sufferer is caught in a process of medicalization that takes hold of them and defines them as a patient tagged with their name and number. The person disappears, says Lock, “transformed into a thoroughly decontextualized AD case . . . reduced entirely to neuropathology.” This depersonalization is apt to aggravate the condition and may lead to overdiagnosis and overtreament, especially for those who end up in care homes.

All this sounds like Albert Einstein’s apocryphal definition of insanity: doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results. The outcome was that other approaches were cut off. Questions about external and environmental influences were even more elusive, although there was speculation about the benefits of education and physical fitness and about the role of the plasticity of the healthy brain that gives it “reserve capacity.”

Researchers gathered demographic evidence that people and social classes who lack such benefits are more susceptible. The incidence of dementia is higher among women than men, and among Hispanics and African Americans as opposed to white people, and it increases as family income decreases. This pattern clearly implicates social and environmental rather than medical factors.

Image Sleuthing

Now comes Charles Piller’s book, building on a series of articles for Science magazine, which exposes a culture of scientific fraud and complicity. Doctored presents evidence that a number of leading authorities in the field, generally ones supportive of the amyloid hypothesis, have been responsible for falsifying their lab studies by doctoring the images used to demonstrate the data.

At issue was a test called the “western blot” that measures the amounts of specific proteins within a tissue sample. When these images are stained in the lab and illuminated on a digital display, they appear in a ladder-like pattern of stacked bands; the thicker the bands, the more of that particular protein in the sample.

As with any photographic image, it is easy to doctor the blots by using software such as Photoshop. With such readily available tools to hand, bands can be copied and pasted; their shapes can be adjusted, their intensity manipulated, and their backgrounds altered.

Scientific dissenters have revealed such doctoring through close examination of images with AI programs. These “image sleuths” were Piller’s informants. The book is a racy journalistic account of dozens of cases involving apparent misconduct in Alzheimer’s research by top scientists.

These are (or were) leaders of the field who headlined big conferences and started their own biopharma companies. They served as each other’s peer reviewers, cited each other’s papers, and edited the journals they published in. They also controlled career opportunities and the award of grants to each other. This “amyloid mafia” fostered a scientific monoculture that depleted the research landscape around it.

The image sleuths uncovered more than image doctoring. Sometimes different papers used the same image to represent different results. Above all, the results were not replicable — the acid test of scientific method.

When they made their concerns known through the proper channels, the doubters often met with stonewalling by editors, or the regulators threw the problem back at the universities that employed the scientists involved. The institutions dragged their feet to avoid unwelcome scandal.

Piller shows how, in the end, authors and journals were forced to retract many much-cited papers, casting a shadow over the entire publishing and peer review system. The scandal ruined reputations, and the companies associated with the tainted figures saw their share prices badly affected. One of those firms ended up with a fraud indictment for allegedly fabricating data.

Deception and Destruction

I can imagine a bold, independent producer, if there are any still out there, picking this book up and turning it into a thriller-as-exposé. Yet clinical trials with volunteers taking futile medication, which can cost billions of dollars and take many years to complete, are still continuing when they should be stopped. Grants are still being awarded to start-ups and patents licensed on the basis of bad and apparently fraudulent science.

At least, Piller argues, there are signs that the tide has turned, with more funds beginning to flow toward alternative avenues of research. That would be good of course, but for those afflicted, the problem remains. They are caught in a medicalized system in which care is sacrificed on the altar of cure in the name of private profit. But the gods aren’t bothered.

I am currently writing a book about the way dementia is represented on-screen. Reading Piller’s book after watching films that feature digital brain imagery of various types, I find myself prompted to ask what it is that we are being shown and invited to take on trust as authentic representations, if such images may have been tweaked. The ordinary viewer can’t understand them anyway, except as icons of a bewildering terror.

This pales beside the bitter irony of what is currently happening. Robert F. Kennedy Jr is dismantling an admittedly dysfunctional system in the name of “radical transparency,” calling for anything “that advances human health and can’t be patented by pharma” to receive priority. But the rhetoric of Trump’s health secretary is hollow.

I don’t imagine that he is thinking of diverting any of the vast sums invested in tendentious science to support music therapy in care homes, for example, or others ways of promoting the good vibes that are well known to alleviate symptoms, reconnecting even late-stage sufferers who have lost the capacity for speech with their emotional memories.

The report that I began with quotes an Alzheimer’s researcher at the University of Pittsburgh who has been forced to reduce her laboratory budget by three-quarters: “I’m interested in what lived experience does to brain aging. That’s not something shareholders in a private company are going to be interested in because they can’t monetize that.”

If this is the problem, it isn’t one that Trump created — responsibility lies with the medicalized wing of the government-industrial complex. But he and his administration are not cleaning it up — they’re destroying it, and nothing good can come of that.