Democrats Learned to Love Class Dealignment

The neoliberal economic program embraced by the Clinton-era Democratic Party alienated many working-class voters. Democrats responded by reorienting their electoral strategy toward professional-class voters, accelerating workers’ departure from the party.

US presidents Joe Biden, Barack Obama, and Bill Clinton attend a memorial service for Ethel Kennedy at the Cathedral of St Matthew the Apostle in Washington, DC, on October 16, 2024. (Jim Lo Scalzo / EPA / Bloomberg via Getty Images)

Right on schedule — and as they had done countless times before — pundits of the center left followed up the Democratic Party’s drubbing with autopsy reports, many of which tried to absolve the party of responsibility for its own defeat. Among the most unsavory of these attempts at absolution were those that blamed Democrats’ loss on the betrayal of the party by working-class voters.

Writing in the Washington Post, for example, Fareed Zakaria urged the party to accept the harsh lesson of the election: “Biden failed to win the working class. Democrats might want to stop trying.” It is past time, Zakaria argued, for Democrats to stop “pining for the working-class whites whom they lost decades ago” and to embrace their new “solid base of college-educated professionals, women and minorities.” Never mind that, as 2024 clearly indicated, the party’s problems now extend to working-class minorities. “Perhaps,” Zakaria mused, Democrats “should lean into their new base and shape a policy agenda around them.” He asserted that “Biden’s presidency has been an important test of a powerful theory.” This theory was that “the party’s shift to more market-friendly economic policies was a mistake.” The solution, or so the Biden neo–New Deal Democrats hoped to show, was to bring working-class voters back with “economic policies infused with [a] new interventionist spirit.” But, Zakaria maintained, November’s election showed just how wrong these illusions were.

In a similar manner, Jonathan Chait at the Atlantic chided those who advanced the faulty theory, in his mind, that “Donald Trump’s 2016 election represented a voter backlash against ‘neoliberal’ economic policies that had impoverished people in the heartland.” Partisans of this theory preferred to believe that these voters, “in their desperation,” had “turned to a populist outsider promising to smash the system that had betrayed them.” These were the ideas that animated the Biden presidency. Yet Biden’s relentless overtures to workers and his decision to “support labor unions categorically” went nowhere. “The electorate’s diffidence in the face of these measures is bracing. The notion that there is a populist economic formula to reversing the rightward drift of the working class has been tried, and, as clearly as these things can be proved by real-world experimentation, it has failed.”

Even the New York Times‘ Ezra Klein leaned on the election results to make a similar point. Klein said, “Democrats worked damn hard over the past few years to deliver what they thought, what they were told, Black and Hispanic and working-class and union voters wanted. And instead of solidifying support from those voters, they’re seeing them flee to Donald Trump.” This was particularly perplexing because, as Klein reasoned, the party had been moving leftward on economic questions since 2000. “Barack Obama was well to Bill Clinton’s left. Hillary Clinton ran on an agenda well to Barack Obama’s left. Joe Biden ran on an agenda — and governed on an agenda — to Hillary Clinton’s left.” Zakaria, Chait, and Klein were of course responding to something real and notable about the party’s defeat. In the presidential election, 59 percent of white middle-class voters voted for Kamala Harris, compared to just 31 percent of the white working class. Harris’s support was higher among black and Latino people, but her support among both groups was down from Joe Biden’s showing in 2020. Among black voters without a college degree, it dropped 3 percentage points from Biden’s in 2020, and among those making less than $100,000, Harris’s share dropped 8 percentage points. More strikingly, among Latino voters without a college degree, her share was down 15 percentage points; among those making less than $100,000, it was down 20. The 2024 election provided yet more proof that Democrats’ long-standing base of support in the American working class is in a state of advanced decay. And the defection of working-class voters from the Democratic Party now seems to be a general trend, no longer confined only to whites.

But Zakaria, Chait, Klein, and others like them muddle the history of the party they are trying to resuscitate. The day after Election Day, Bernie Sanders put out his own pithy autopsy: “It should come as no great surprise that a Democratic Party which has abandoned working class people would find that the working class has abandoned them.” Sanders’s account was far more concise and much more accurate.

This article develops the basic insight at the core of Sanders’s account. The argument in brief is as follows.

Class dealignment is the process by which the historic coupling of workers and the center left, on the one hand, and the middle class and the center right, on the other, has been broken. Class dealignment in the United States has its origins in definite and conscious decisions made by the Democratic Party beginning in the 1980s that were then enacted in the 1990s and defended ever since. The party’s embrace of a neoliberal economic program — including free trade and balanced budgets at the expense of social spending — was the opening shot in the process of class dealignment. The negative consequences of this economic program for the party’s erstwhile working-class supporters in industrial America were so predictable that its top strategists inside the Clinton administration explicitly predicted them. But they nevertheless pushed ahead and plunged the party into an electoral crisis. This was a crisis that Democrats’ new leadership then celebrated as a great opportunity. The moment had come to shed their image as a class party — a debilitating relic of the New Deal era, or so party leaders came to think. It had to be seized. The future of the party lay in a new alliance between white middle-class voters and people of color of all social classes, and the class politics of the 1930s were poorly suited for this purpose. By the mid-2000s, the party’s enthusiastic pivot toward the middle class was visible in the redirection of its fundraising energy and dollars. Its electoral targets moved toward much more affluent, majority-white districts in the country’s booming postindustrial metropolises.

While Democratic political strategists spent the aughts enthusiastically bringing the party’s electoral strategy into line with its economic program, its economic strategists grew more wary of what was on the horizon. In prescient, almost eerie accounts, leading Democrats warned of a coming backlash against globalization. Key members of the party’s central economic team around the Goldman Sachs banker Robert Rubin began to sketch out how it should adjust course and shore up broader support for the economic model developed under Clinton. These concerns gave rise to a renewed interest in social insurance and economic inequality. It’s in this pivot by the party’s economic strategists that we can find the origin of the leftward adjustments under Obama and Biden. But these adjustments were tightly circumscribed by foundational assumptions that Democrats carried over from their Clinton-era reinvention: a steadfast commitment to free trade, an unflinching devotion to winning business’s blessing for any expansion of the social safety net, and — at least up until the election of Biden in 2020 — a wariness about the influence of organized labor. This was hardly a sharp turn to the left to cancel out the party’s prior rightward turn. Major reforms like expanding national health insurance and resecuring labor’s right to organize — reforms that might have revamped the party’s populist image and strengthened the hand of unions — could never overcome the limits set by the party’s fundamental commitment to the program articulated during its 1980s neoliberal turn to the right.

Class dealignment, in short, should be understood as a result of Democrats’ policy decisions in the 1990s and their work since 2000 to actively bring their electoral strategy into line with their economic program. Contra Zakaria, Chait, Klein, and others, Democrats were the first movers in this process. The scant material support delivered in recent years by way of post facto compensation to working-class voters hit hard by neoliberalism and globalization — and workers’ concomitant failure to respond in the desired way — can be chalked up to a case of too little, too late.

The 1990s as a Turning Point

Pundits rushing to place blame on working-class voters for abandoning Democrats typically reach for one of two explanations for class dealignment. Both focus on variations of the proposition that a fundamentally conservative working class has gravitated toward its natural home in the Republican Party. The first explanation dates dealignment to the late 1960s and early 1970s and a national backlash against the civil rights movement, second-wave feminism, and antiwar activism. This backlash supposedly was most acute among white working-class voters who were drawn to a Republican Party that was all too willing to accommodate workers’ reactionary ideas. The second theory dates class dealignment to the last eight years. In this account, Donald Trump’s toxic brew of nativism and sexism succeeded in cleaving off a sizable chunk of Democrats’ white working-class base in the 2010s.

Often the explanations are combined. In Zakaria’s rendering of the problem of class dealignment, for example, he brings the two together. “Ever since the Democratic Party embraced civil rights in the 1960s, it has been slowly losing the votes of the white working class, largely on issues related to race, identity and culture. This shift accelerated over the past 20 years as the party moved further left on social and cultural issues.”

Accounts of these types, however, are not compelling. Far from being the result of a long-running backlash dating to the 1960s or a sudden change in the last eight years, class dealignment in the United States is a process that really took off in the 1990s and the years that followed.

To explore these questions more fully, figures 1 and 2 chart the rise and fall of support for Democratic presidential and congressional candidates among white working-class and middle-class voters. The graphs (and this section) focus on white voters because it’s among this group that we first see substantial evidence of class dealignment in the 1990s. A similar pattern among people of color may now be taking shape, but it is of a much more recent vintage. To understand the origin and causes of dealignment, therefore, we must look to the pool of voters among whom it first surfaced.

As the figures make clear, there was undeniably a backlash against the civil rights movement (and other social movements of the 1960s and ’70s) that depressed support for Democrats, and particularly Democratic presidential candidates. Between 1968 and 1992, Democrats lost all but one of the presidential elections, most by substantial margins. The seemingly obvious explanation is a falloff in support for Democratic presidential candidates among white voters with culturally reactionary politics. But as figure 1 also demonstrates, this backlash in presidential elections did not have a clear class character. Democratic support was depressed among white working-class and middle-class voters alike. Moreover, the extent of this backlash against Democrats remained mostly confined to its presidential candidates. Democrats continued to dominate congressional elections, both inside and outside the South.

As the figures make clear, there was undeniably a backlash against the civil rights movement (and other social movements of the 1960s and ’70s) that depressed support for Democrats, and particularly Democratic presidential candidates. Between 1968 and 1992, Democrats lost all but one of the presidential elections, most by substantial margins. The seemingly obvious explanation is a falloff in support for Democratic presidential candidates among white voters with culturally reactionary politics. But as figure 1 also demonstrates, this backlash in presidential elections did not have a clear class character. Democratic support was depressed among white working-class and middle-class voters alike. Moreover, the extent of this backlash against Democrats remained mostly confined to its presidential candidates. Democrats continued to dominate congressional elections, both inside and outside the South.

Thus, up until the 1990s, changes in support for Democrats among both groups moved roughly in tandem, with Democrats consistently garnering more support from white workers than Republicans did (with the notable exception of the 1972 presidential election, though an especially strong swing away from Democrats by workers is balanced by a strong swing back to them in 1976). This general pattern ends in the 1990s. It’s in this pivotal decade that support for Democratic candidates from both social groups stops moving roughly in sync. White working-class voters’ support for Democrats in presidential elections declined in the ’90s and early 2000s, rebounded somewhat in the 2008 presidential election, and then declined significantly in the 2010s. In congressional elections, support for Democrats among white workers fell dramatically in 1994, then flatlined before declining further in the 2000s. On the other hand, support for Democratic candidates among middle-class whites rose through the ’90s, more or less flatlined in the 2000s, and then began a rapid ascent in the 2010s.

Identifying these two distinct periods in the postwar voting behavior of white middle-class and working-class voters allows us to focus in on the 1990s as dealignment’s takeoff point. In the ’90s, the pattern marked by higher support for the Democratic Party among white workers than among white middle-class voters — but with ebbs and flows in both groups’ support that moved in tandem — came to an end. In its place a new pattern emerged in which support for Democrats from each group began to move in opposite directions.

The figures also show that there was something distinct about the 2016 election and Donald Trump’s presidential bid. Class dealignment accelerated starting in 2016. Trump simultaneously drew a significant portion of white workers who had previously voted for Obama while repelling some of the Republican Party’s once solid middle-class supporters. But placed in the context of the longer story of class politics in the United States, Trump’s role as an accelerant of class dealignment that was already in process becomes more evident.

If the ’90s marked the onset of class dealignment, identifying its cause becomes the next task. A significant shift in the voting behavior of a social group can logically have only two potential causes. On the one hand, the preferences of a group can change in some meaningful way, altering what they seek from parties and therefore their voting behavior — a change on the “demand side.” On the other hand, the preferences of a social group may hold steady while the nature of party competition shifts, altering what parties offer to voters — a change on the “supply side.” This can in turn provoke a change in voting behavior.

Of these two accounts, the demand-side explanation can be ruled out from the jump. There was no widespread and sudden rightward lurch on either economic or cultural issues by white working-class voters in the ’90s. Given that, our attention must focus on the supply side of the ledger.

There was a shift in the political program of the Republican Party in the thirty years between 1960 and 1990. The party had long been hostile to New Deal-era reforms, but after 1960 Republicans became more aggressive in their opposition to these policies, culminating in the “Reagan Revolution” and a wholesale attack on progressive income taxes, regulations, unions, and the welfare state. While this was a shift in the level of the party’s zeal for overturning the New Deal, the party also consolidated around a new orientation to civil rights and social issues. In its effort to capitalize on hostility to the Democratic Party in the 1960s and ’70s, Republicans embraced a much more socially conservative program on race, gender, and sexuality. As is well known, the party’s growing alliance with Christian fundamentalists in these years played a significant role in this transformation.

However, the Republican Party’s rightward shift on cultural politics and its more strident defense of free-market economics came too soon to be a compelling cause alone for the beginning of class dealignment in the ’90s. And it’s difficult to see how its more aggressively right-wing politics on economic questions in particular would attract working-class voters who had long preferred Democrats precisely because of the party’s more left-leaning positions on the economy. For a better explanation, therefore, we need to look as well at shifts in the “supply” of policies offered by the Democratic Party.

Bill Clinton and the Democrats’ New Economic Policy

Under the administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt and under the pressure of popular movements, Democrats succeeded in rewriting some of the rules of American capitalism in workers’ favor. Social Security guaranteed Americans a public pension in their old age. The National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) secured workers’ rights to form a union and bargain collectively — rights that millions of workers quickly made use of as national union density skyrocketed. The federal government took on substantial new responsibilities for providing relief to the unemployed and social support for the poor. And the Fair Labor Standards Act set a national minimum wage and a maximum hours standard. Democrats under Lyndon B. Johnson expanded on this record with the launch of Medicare, Medicaid, and a bevy of programs to support the poor, including food stamps and Pell Grants to help low-income students go to college.

Despite all the limitations of the party’s program (especially by comparison to the much more ambitious agenda and success of social democratic parties elsewhere in the advanced capitalist world), the social consequences were significant. A moderate level of union density, a strong progressive income tax regime, and a growing welfare state led to rising living standards and historically low levels of income and wealth inequality. The party was widely seen as the representative of the country’s working class and all those who were less well-off, and the postwar class alignment in voting reflected this.

In the face of the economic crises of the 1970s and the anti–New Deal “business offensive,” however, the party faltered under Jimmy Carter. Abandoning its 1976 commitments to national health care, labor law reform, and full employment, the Carter administration desperately sought pro-business solutions to the country’s economic malaise. Democrats enacted capital gains tax cuts, deregulated key sectors of the economy, and accepted punitive interest rate hikes that were designed to tamp down inflation.

A recession doomed Carter’s reelection chances and paved the way for Ronald Reagan’s victory in 1980. The defeat, however, served not as a catalyst for the reinvention and elevation of the party’s liberal wing but as a boon to its business-friendly moderates. Pushed by a mobilized corporate world and hounded for being insufficiently pro-market, Democrats — suffering especially from the party’s dismal fundraising compared to the GOP — executed a right turn. Over the next decade, Democrats in Congress and in the constellation of donor circles and think tanks worked relentlessly to move the party away from its New Deal roots.

These efforts bore fruit in the formation and execution of Bill Clinton’s economic agenda. In the years leading up to Clinton’s 1992 victory, the party’s leading fundraisers, power brokers, and their allies (spanning the worlds of finance, Democratic Party politics, and academia) carefully set a new economic policy. Leading figures in these circles included Rubin — who would join the Clinton administration first as head of the new president’s National Economic Council and then as his Treasury secretary — and the Blackstone Group’s Roger Altman. Their allies, who would also play an important role in the Clinton administration, included senior figures like Lloyd Bentsen, a Texas banker and then senator who became Clinton’s first Treasury secretary, and more junior figures like the Harvard economist Lawrence Summers.

The Democrats’ new economic policy was aimed at pulling the country out of a period of sluggish economic growth by bringing down the cost of capital needed to juice private sector investment. Rubin, Altman, and Summers were among the most articulate and vocal spokesmen for this approach. If the cost of investment in the United States could be brought down, the party’s economic strategists hoped, the private sector could begin to make riskier, longer-term investments in the industries of the future: semiconductors, computing, robotics, and biotechnology being the most alluring. These industries would be, in the words of Altman and Summers at a major Democratic Party policy conference in 1989, the “big jobs programs” of the future, taking the place of the country’s “dying sunset industries.” The party’s economic strategists reasoned that the high cost of capital in the United States — measured usually in terms of long-term interest rates on US government debt — could most quickly be brought down by winning investor confidence in the new Democratic administration and restricting government borrowing. Both moves required budget austerity and an especially attentive stance toward business interests and concerns. And to turbocharge the country’s leap forward into the new economy, economic strategists urged their fellow Democrats to promote financial deregulation and free trade, policies that would allow financial institutions to consolidate through mergers and then more easily penetrate foreign markets.

This economic agenda became the playbook for the Clinton administration. The new administration’s budgets prioritized deficit reduction (achieved through cuts to social spending and tax hikes) at the expense of almost all other concerns. And Clinton consequentially became a strident defender of free trade, most notoriously through the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) with Canada and Mexico. These two moves became the Democrats’ most notable achievements in Clinton’s first term. In its second term, the administration continued to advance its free trade agenda through the negotiation of China’s entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the permanent opening of the United States to Chinese imports. It also succeeded in deregulating the financial industry through the passage of the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act.

The social and political consequences of the Clinton administration were profound. The focus on deficit reduction hamstrung most of Clinton’s other priorities, including job training programs and national health insurance — denying the administration and the party significant wins in social policy that could have burnished its populist appeal. But most important, the passage of NAFTA created the impression that Clinton had chosen to forsake the party’s base among industrial workers. NAFTA hit counties that were reliant on manufacturing and vulnerable to outsourcing to Mexico especially hard. Estimates show that these counties lost roughly between two and five jobs for every one hundred residents by the end of Clinton’s second term. Not incidentally, these had been among the most loyal Democratic counties in House elections. The effects on the party’s electoral fortunes were serious: Democratic support in hard-hit parts of the country and among all voters more opposed to free trade (who were disproportionately lower-income) dropped significantly.

The political consequences of Clinton’s program were fully understood by the party’s strategists. Before Clinton’s inauguration, his political advisers warned that the agenda put forward by the Rubin team would destroy the livelihoods and communities of many in the party’s base and that this would cost it significantly in elections to come. Even supporters of deficit reduction and free trade in the administration acknowledged that the program would seriously damage the party’s standing among its working-class base. William Galston, a leading member of the party’s New Democrat wing and Clinton’s deputy assistant for domestic policy, put it this way:

There is no way that [Clinton] polled his way to a Bob Rubin economic plan. . . . You didn’t have to take more than a week of Democratic Politics 101 to know what a free trade agenda was going to do to the party. . . . From the standpoint of the Democratic Party electorate, with unemployment still very high, historically that is a very poor climate for a free trade agenda.

But Galston and many others like him, especially in the ascendant New Democrat wing, considered these problems to be costs worth absorbing. The long-term payoff to the country and the party as the economy rebounded and entered a new period dominated by high-tech, high-wage jobs — so the argument went — would be immense. This would be Clinton’s and the Democrats’ great legacy.

An Electoral Strategy Fit for a New Economic Policy

The political blowback from the Clinton agenda came swiftly. The 1994 midterm elections (the first after the passage of NAFTA), the abandonment of health care reform, and the embrace of budget austerity delivered a crippling blow. For fifty-two out of the sixty-two years from 1933 through 1994, Democrats controlled both chambers of Congress. Not since 1954 had Republicans controlled both simultaneously. But in the biggest midterm wipeout since the end of World War II, Democrats lost fifty-two seats in the House and eight seats in the Senate, enough to hand control of both chambers to the GOP. At the state level, Democrats also lost ten governors.

In the wake of this electoral disaster, most assumed Clinton’s reelection chances were slim. Despite these fears, he was able to recover enough support by 1996 to win reelection, driven in part by public dissatisfaction with the speakership of Republican Newt Gingrich. But Clinton’s victory did nothing to revive Democrats’ fortunes downballot. Thus a larger debate unfolded in the late 1990s about the party’s future, its political strategy, and its social base. Faced with a downballot crisis, Democrats had to either roll back much of their neoliberal economic agenda or find a new political strategy that would be compatible with it. They chose the latter.

In the ensuing debate in the ’90s and early ’00s, those hewing to the party’s liberal wing argued that Democrats had to return to their populist roots. Only a populist economic agenda, emphasizing redistribution and economic security, could hope to resecure support for the party among working-class voters.

Against the liberal position were arrayed the party’s “moderates” (whose chosen moniker was “New Democrats”) organized around the Democratic Leadership Council (DLC) and its think tank the Progressive Policy Institute. Although the DLC’s electoral strategy in the ’80s had focused on winning back white Southerners, by the late 1990s its aims had shifted. An electoral strategy was needed that meshed with the party’s new economic program. The DLC found one in a call to reorient Democrats toward the country’s growing professional class and voters in affluent, college-educated suburbs. These were the soon-to-be — or so the DLC hoped — mass base of the developing postindustrial economy.

For these New Democrats, there was much to be hopeful about. Despite the rest of the party’s dreary results, they believed that Clinton’s reelection prefigured a bright future to come. First and foremost, Clinton’s chief pollster, Mark Penn, accredited the president’s 1996 win to substantial gains in suburban America. Clinton won twenty-four of the country’s twenty-eight largest suburban counties, more than two-thirds of which had not gone for a Democrat since the ’60s. These advances built off the gains of a generation of “Atari Democrats” who had individually been making headway in congressional races in more affluent, suburban districts in the two decades prior. These Atari Democrats (named after the video game and computer hardware company because of their enthusiasm for the tech industry) ran on economically conservative platforms and had served as proof at the local level that the party could win over professionals.

Clinton’s 1996 reelection campaign was thus celebrated as the national launch party for this strategy. New Democrats argued that the early victories of the Atari Democrats and now Clinton’s breakthrough in suburban America demonstrated that the party could be viable in parts of the country that had once been the GOP’s exclusive domain. This would not just buttress the party’s existing base of support; it offered Democrats a whole new path back to electoral success, and with a voter coalition that would be far more aligned with the party’s new economic policy.

But to secure its future and a base in this new white-collar majority, Democrats would need a new kind of politics, one marrying pro-business policies and rhetoric with a more liberal approach to social and cultural issues. The class politics of the New Deal were of diminishing significance and even a threat to the party’s future, as they could alienate the new middle-class voters it so desperately needed to attract. As the DLC’s CEO, Al From, put it in 2001:

This is the bottom line: The New Economy is creating a new electorate that demands a new politics. The sharp class differences of the Industrial Age are becoming less distinct as more and more Americans move into the middle and upper-middle classes. The New Deal political philosophy that defined our politics for most of the 20th century has run its course; the political coalition it spawned has been split. Like Humpty Dumpty, the New Deal coalition cannot be put back together again. The new electorate is affluent, educated, diverse, suburban, “wired,” and moderate. And it responds more favorably to the New Democrat political philosophy than to any other.

The New Democrats’ case was further strengthened in the early 2000s by the liberal strategist Ruy Teixeira. Teixeira had formerly been of the opinion that the party needed to rebuild its base in the working-class “forgotten majority,” the title of his 2000 book on party politics. But in 2002 Teixeira published The Emerging Democratic Majority with his coauthor John Judis. Judis and Teixeira focused on the Democrats’ opening to build a centrist national majority based among professionals, women, and people of color. For Judis and Teixeira, the party’s right turn away from its New Deal legacy had been the key to unlocking this opportunity. “Professionals might not have moved toward the Democratic Party,” they wrote, “if the party itself had not moved toward them.” Clinton’s administration had been the key to solidifying this. His and other party moderates’ “general approach has helped to reassure professionals leery of overly ambitious government programs and to make the Democratic Party the natural home of the professional voter.” As for the white workers who Teixeira had previously seen as being a “forgotten majority,” their position was demoted. Democrats now needed only to hold down their losses and secure a “respectable showing” among them.

The emerging consensus among Democratic political strategists at the start of the century identified the party’s future in the country’s postindustrial metropolises, combining both the urban core and its affluent suburbs — places like the San Francisco Bay Area and North Carolina’s Research Triangle. These ideas found their way into party practice through changes in the Democrats’ target districts and the reallocation of party resources. Leaders, donors, and a new cadre of “Netroots” activists alike converged on this theory. The party’s greatest opportunities for rebuilding a national majority lay in flipping affluent Republican-held districts in what could become solid-blue postindustrial metropolitan regions.

As one Democratic operative at a leading consulting firm put it after the fifth consecutive defeat of efforts to retake the House in 2004: “I’d stop wasting money trying to beat Rep. Anne Northup (R-KY). . . . Look at blue state Republicans who haven’t had a tough race and put some pressure on them.” Democrats had to, in other words, stop pursuing districts in less affluent parts of the country, like Northup’s Kentucky district, even though “on paper it says it’s a Democratic district.”

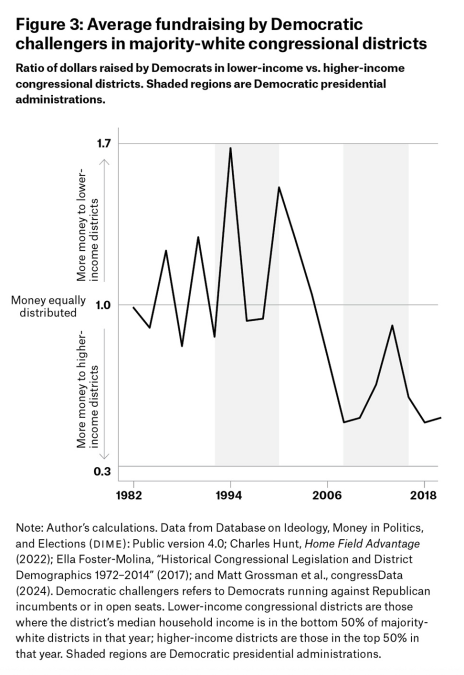

Figure 3 shows how the party’s key resource — campaign funds — were actually reallocated along these terms in the 2000s. The graph charts the ratio of dollars raised by Democratic candidates running in majority white districts against Republican incumbents or in races with no incumbent, dependent on whether their district was more or less affluent. More affluent districts are those with median household incomes in the top 50 percent; less affluent districts are those in the bottom 50 percent. Prior to the aughts, the ratio of dollars raised by candidates in less affluent districts to those in more affluent districts hovers around 1:1, with candidates in less affluent districts generally raising more in midterms and candidates in more affluent districts raising slightly more in presidential election years. If anything, there was an overall bias in the flow of dollars toward candidates running in the poorer half of majority-white congressional districts.

But by the aughts, a distinctly new trend emerges. Year over year, funds for Democrats in less affluent majority-white districts fall compared to funds for Democrats in more affluent majority-white districts. As the figures suggest, therefore, the energy and attention of the party — measured in the flow of dollars — had shifted noticeably along the lines prefigured by the debate over electoral strategy in the years prior. These trends in funding and prioritization have continued since. When Senator Chuck Schumer told reporters in 2016 that “for every blue-collar Democrat we lose in western Pennsylvania, we will pick up two moderate Republicans in the suburbs in Philadelphia, and you can repeat that in Ohio and Illinois and Wisconsin,” he was echoing what had by then become common sense among many Democrats about how to win elections.

Barack Obama and the Corporate Filter

Following the end of Clinton’s presidency, his former Treasury secretary Robert Rubin and other economic strategists retained an enormous degree of influence in the party. When, for example, AFL-CIO leaders called a private meeting to push back against Wall Street financiers’ influence over John Kerry during his 2004 presidential campaign, they were astonished to discover Kerry already convening with Rubin and Altman. When the meeting concluded, Rubin and Altman remained while the AFL-CIO officials were shown the door. As one attendee put it after the fact: “Wall Street was in the room before we arrived, and they were there after we left.” Rubin, Altman, and Summers conferred regularly with Kerry, prepping the candidate for policy debates and conducting what one paper dubbed a “tycoon tutorial.” Kerry returned the favor by floating Rubin’s name as a possible successor to Alan Greenspan as chair of the Federal Reserve. When, two years later, newly elected Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi organized two panels to discuss policy with House Democrats, she invited three experts to discuss defense issues and delegated economic questions to a panel of one: Robert Rubin.

In 2006, Rubin, Altman, Summers, and other influential Democratic Party economic strategists, donors, and leading Wall Street financiers — looking to formalize and expand their influential roles in party circles — launched the Hamilton Project. Affiliated with the Brookings Institution, the project served as a government in waiting and a policy shop for the next Democratic administration. The Hamilton Project pursued two goals: First, building off of Clinton’s achievements, it tried to deepen Democrats’ commitment to neoliberal economics, free trade, and deficit reduction. This was very much in keeping with the main thrust of Clinton’s two terms. But second, it added a new concern for addressing some of the harsher effects of globalization and deregulation.

This second feature of the Hamilton Project’s agenda made its way into much of the public messaging around its launch. The project’s explicit goal, as its first director and later Obama’s Office of Management and Budget director Peter Orszag put it, was to “head off the argument that the solution to wage stagnation lies in protectionism.” This theme was also the subject of Obama’s keynote speech at the project’s 2006 founding meeting. Obama told the audience that he and Rubin had “had a running debate now for about a year about how [we] deal with the losers in a globalized economy.” The cost of not figuring out a suitable answer to this question — an answer that had to be compatible with the group’s commitment to defending free markets and globalization — would be severe, Obama argued:

Just remember, as we move forward, that there are real consequences to the work that is being done here. There are people in places like Decatur, Illinois, or Galesburg, Illinois, who have seen their jobs eliminated. They have lost their health care. They have lost their retirement security. They don’t have a clear sense of how their children will succeed in the same way that they succeeded. They believe that this may be the first generation in which their children do worse than they do. Some of that, then, will end up manifesting itself in the sort of nativist sentiment, protectionism, and anti-immigration sentiment that we are debating here in Washington.

With an eye to staving off a “backlash that can threaten prosperity,” Altman, Orszag, and Rubin then coauthored strategy papers in 2006 and 2008 that helped set the agenda for the administration to come. What was needed was a mix of fiscal discipline to ensure market confidence (including reducing the cost of Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid) and a controlled expansion of the social safety net “without unduly weakening work incentives.” Their papers advocated new education investments and stricter management of public school teachers as well as job training programs. Income security for Americans should be strengthened through health care reform to expand coverage and reduce costs, programs to help workers who had been laid off from jobs outsourced abroad who “accept new jobs at lower salaries,” and new schemes for encouraging retirement savings.

At the same time, while acknowledging some of the oversights of the Clinton administration, the Hamilton Project conveners had no truck with the demands of its party’s populist dissidents. As one Hamilton Project advisory board member put it, income inequality was the “mother of all electoral issues” in the aughts, but firm action by the party’s centrists was needed to address the issue and ward off the Democrats’ “more extreme factions” who were “trumpeting unionization and protectionism.” (Unsurprisingly, rebuilding the labor movement played no role in the Hamilton Project’s thinking about the next administration.) Obama’s keynote speech, while acknowledging some of the shortcomings of the party’s 1990s program, underscored this basic point. While renewed attention to boosting economic security for distressed workers might be needed, Obama prefaced his remarks by saying, “If you polled many of the people in this room, most of us are strong free traders and most of us believe in markets.”

The Hamilton Project’s work then directly informed the transition into the Obama administration. As the managers of Clinton’s economic program, Rubin, Altman, Summers, and others around them held influential positions in this process. In internal memos, they sketched out plans for strengthening the social safety net while winning investor confidence and remaining committed to the long-term goal of reducing the deficit and debt. The administration and its advisers may have been more attuned to the need to enact policies to support the country’s working class than Clinton had been, but they would do so within narrowly set limits.

In office — and with an economic team pulled from the rosters of the Hamilton Project — Obama’s administration worked diligently to carry out this vision. Drawing strength from mounting support in the corporate world for health care reform, the administration’s flagship reform effort, the Affordable Care Act (ACA), limped across the finish line in early 2010. The ACA contained policies eagerly sought by its corporate supporters in the insurance industry, including, most prominently (and with significant public hostility), an individual mandate requiring all Americans to buy health insurance. It also included some important reforms that undeniably improved conditions for working-class people, including abolishing the practice of charging those with preexisting conditions higher rates and expanding Medicaid to cover millions more people.

Other efforts that lacked a clear base of corporate support failed to advance. As numerous polls at the time demonstrated, the public option, a piece of Obama’s health care plan during the 2008 campaign, had widespread public support. But it was fiercely opposed by the corporate world (the exact opposite of the problem that faced the individual mandate). Despite its broad popularity, however, the Obama administration never championed the public option after coming into office. In a deal with executives and their representatives in the health care sector, the administration eventually traded it away in return for promises of cost cutting and health industry support for the ACA. Although this trade was never publicly acknowledged by the administration, multiple accounts — including by top industry lobbyists and former Democratic Senate majority leader Tom Daschle, who was involved in the Obama administration’s health care planning (though Daschle later recanted his account) — support this conclusion. These negotiations with industry and the decision to remove the public option came months before beginning conversations with Congress to secure sufficient Democratic support for passing the overall package. The fact that the public option was intolerable to the very firms the Obama administration hoped to collaborate with on reinventing health insurance and extending coverage decided its fate.

Similar fates awaited the administration’s climate proposals, more aggressive plans for regulating the financial industry, and labor law reform. Although it is doubtful that the administration’s core economic team had much enthusiasm for these proposals, corporate opposition to their mere consideration was fierce, and the Obama administration was repeatedly confronted with threats of an investment strike if it crossed business’s many policy red lines.

In the case of the Employee Free Choice Act (EFCA) — which was labor’s top priority and would have made union organizing significantly easier — the administration took a position of careful indifference and allowed it to die from neglect, despite the fact that leading Democrats claim to have had the votes needed to overcome a filibuster. Iowa senator Tom Harkin, who took charge of shepherding the EFCA and finding the votes to pass it in the Senate, insisted years later that he had succeeded in getting the sixty necessary votes to kill a filibuster of a modified version of the EFCA by September 2009. Having overcome the filibuster, Harkin and Democrats would have had enough votes to pass the EFCA, even if a few Democrats went on to vote against the final bill in the Senate’s byzantine processes. But according to Harkin, the Obama administration instructed Senate majority leader Harry Reid not to move forward with labor law reform until the ACA had passed. The administration continued stalling, despite Harkin’s protestations, into January, at which point the Democrats lost their sixtieth vote after the untimely death of Democratic senator Ted Kennedy and his replacement with a Republican. This was particularly tragic because labor law reform enjoyed majority approval from the public in most cases, with disproportionate support coming from lower-income voters and voters with no college degree.

As discussed in the previous section, Democratic political strategists worked assiduously to refashion the party’s political strategy to mesh with the natural constituency for its economic program in the years leading up to the Obama administration. At the same time, its economic strategists shifted some of the party’s emphasis back toward questions of social insurance and economic security. This was a defensive action designed to forestall a backlash against the country’s new economic model that party leaders — in a prescient moment — feared was in the offing. Although some have cited these moves as evidence of the party’s leftward shift on economic questions, these accounts greatly exaggerate what actually happened. These were shifts embraced and pushed by the same network of power brokers and party financiers who had designed the economic program of the party under Clinton. Moreover, once in office, the Obama administration set strict limits on the kinds of redistributive programs it was willing to consider. Blaming the recalcitrance of its own party’s right wing, the administration jettisoned the campaign’s most significant reform commitments, including to public health insurance and labor law reform. But these moves were made after the administration took significant heat from the corporate world and after it had demonstrated no desire to pursue such policies. The only significant reforms that the administration enacted — like the expansion of Medicaid — were those for which it could recruit substantial corporate support. In this way, however, the party clipped its own wings and failed to make the kind of decisive intervention that could have allowed it to consolidate the national majority and mandate it had won in 2008. Instead Democrats’ hopes of assembling an “emerging majority” were soon shaken radically by the election of Obama’s successor.

No Second Chance Under Joe Biden

The 2016 election served as a sharp rebuke to the Obama administration, and it unsettled the Democratic Party like few elections had before it. The fact that a democratic socialist mounted a credible challenge for the party’s nomination in the primary elections added to the sense of disorientation.

Amid the fallout, party leaders began to redouble the aughts-era interest in questions of economic security and to gesture at the need to win back working-class voters. Although in 2018 the party had returned to power in the House by winning a significant number of congressional seats in the country’s more affluent white districts, some candidates in the 2020 primary campaign flirted with issues once relegated to the far left of the party, like Medicare for All and a Green New Deal. Joe Biden himself promoted the idea that Democrats needed to return to their blue-collar roots, and his 2020 campaign borrowed themes from the party’s populist heritage.

This greater openness to redistributive concerns and policies as a response to the rise of Donald Trump and the far right was not just confined to the party’s political class. The openness was echoed by its economic strategists and leading figures in business. Even Summers, no champion of the US labor movement, began to draw links between union decline and rising inequality. And with Jason Furman — a new economic strategist coming out of the Obama administration, closely tied to the Hamilton Project — Summers questioned whether the party’s long-standing focus on deficit reduction ought to be deemphasized in the face of large social, environmental, and economic challenges. These calls came from the corporate world as well, as a wave of interest in “stakeholder capitalism,” “ethical” investing, and diversity policies crested. In his shareholder report released just months into Biden’s presidency, for example, JPMorgan Chase CEI Jamie Dimon told investors that Americans were right to blame political and corporate leaders for the fact that “something has gone terribly wrong” in the country’s economy. “The fault line for all this discord is a fraying American dream — the enormous wealth of our country is accruing to the very few.” These failures, Dimon warned, “fuel the populism on both the political left and right.”

Pushed in part by the chaos of the COVID-19 pandemic, the incoming Biden administration committed itself to working with Bernie Sanders and other progressives on enacting an ambitious, multitrillion-dollar reform program. Biden’s first initiative, the American Recovery Plan, a large but temporary stimulus package designed to rescue the country from a crippling recession, was the most significant fruit of this collaboration. It received enthusiastic support from an unusual coalition stretching from labor and progressives to the business press and the wider corporate world.

But the administration’s subsequent efforts to pass more sweeping social spending legislation financed by corporate and capital gains tax increases encountered stiffer corporate opposition. Likewise, its push to rewrite labor law via the Protecting the Right to Organize Act (the PRO Act, a watered-down version of the EFCA) was unacceptable to the business world. But the administration’s most immediate challenge came from its own party, especially its two most conservative senators, Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema. Faced with opposition from both corners, hopes for “building back better” were slowly chiseled away through the first half of 2022. In the end, what the administration was left with was the much reduced in scope Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). Unlike Build Back Better — the Biden administration’s hoped-for comprehensive reform package with significant new social spending — much of the IRA was focused on tax cuts to businesses and the wealthy to make new climate-friendly investments and purchases.

Having forsaken its ambitions for making emergency social safety net expansions during the pandemic permanent, the administration pivoted to a renewed focus on the deficit and foreign policy. Gone were mentions of the Build Back Better plan, replaced by concerns about reducing federal spending. The defeat of the administration’s more ambitious proposals meant that it oversaw the dismantling of the temporary “COVID welfare state.” These were — to make matters worse — also the months of a major rise in inflation. Unsurprisingly, these developments led to a precipitous decline in support for the Biden administration.

To add to Biden’s travails, few Americans to this day know much about what the administration and its defenders tout as their signature accomplishment. Polling suggests that by 2024, somewhere around 40 percent of Americans knew nothing about the IRA’s impact, and a further 20 to 30 percent said the act made little difference for the US economy, workers, climate change, and inflation. Only around 15 to 20 percent of adults believed the IRA had done “more to help” than hurt any of those four concerns. The remainder said it had done more to hurt than help. (35)

What Democrats were left with at the end of the Biden administration was no match for the hopes they carried into 2021. And as the 2024 election demonstrated, the president’s four-year term fell far short of its ambitions to “heal the soul of the nation” and prevent a return to power by Donald Trump. The backlash that the Hamilton Project feared is now in full swing.

Conclusion

In 1958, a Gallup survey asked voters to describe the typical Democrat and the typical Republican. Democrats were, according to respondents, “common people,” “an ordinary” and “an average” person, and someone who “works for his wages.” Republicans, on the other hand, were seen as “better” or “higher” class, “well-off financially,” a “money voter,” and “wealthy.”

More than sixty years later, the two parties have not swapped those images — not yet, at least; talk of a Republican “workers’ party” is still a significant exaggeration — but the old picture of a blue-collar Democratic Party and a white-collar GOP is very much a thing of the past.

This is no accident. The Democrats today are a radically different party than the one carrying all the baggage (or redeeming qualities, depending on who you ask) of the New Deal that went down to defeat by Ronald Reagan in 1980. It is this way in large part because of decisions made by Democratic Party leaders. The termination of the New Deal Democratic Party really began in earnest in the years leading up to Bill Clinton’s election in 1992, when Democratic leaders and key power brokers worked relentlessly to jettison the legacy of class politics. Their work paid off when President Clinton, with many of these same power brokers at the head of his economic team, turned a new, much more capital-friendly economic policy into reality. His agenda had particularly devastating consequences for the party’s once loyal working-class base — costs that party leaders acknowledged and accepted ahead of time. After Democrats lost control of both chambers of Congress in 1994 for the first time in more than forty years, party leaders, totally unwilling to change direction on the economic front, instead reworked the party’s electoral strategy. The consequence was a shake-up in the class alignment of American voters no less significant than the one inaugurated by FDR’s administration and the years of class struggle in the 1930s.

The preceding analysis supports a sharp repudiation of recent apologetics written on behalf of Democratic Party leaders. Democrats’ travails are hardly the result of working-class voters abandoning a party that, as its liberal apologists would have us believe, has bent over backward in the last four years to keep them in the fold. Instead the party’s neoliberal rechristening in the ’90s played a pivotal role in setting class dealignment in motion.

But it is not only the Left and Bernie Sanders who believe this analysis. It was at one point the stated opinion — in both the writings of party insiders and in moments of candor by the party’s public leaders, including Barack Obama — of the Democratic Party itself.

Class dealignment was heralded as an enormous opportunity for Democrats. The 1990s and the aftershocks of the Clinton administration’s economic policy provided the party with precisely the moment it had been waiting for. The time had come to trade in the “sunsetting” blue-collar workers of the New Deal for the “wired” white-collar suburbanites of the New Economy. And rather than waste their energy and efforts on putting Humpty Dumpty back together again — in Al From’s memorable metaphor — in order to fashion some kind of new alliance of blue-collar workers and white-collar professionals, Democrats entered the new millennium with a much more targeted focus on the latter group. As data on the party’s fundraising efforts demonstrate, Democrats in the 2000s rushed with gusto into the work of painting suburban America blue.

But the dark side of class dealignment was a subject of concern in party circles long before it became a popular topic of debate among progressives and scholars. Democrats in the mid-aughts were already discussing the danger of a backlash fueled by nativist and protectionist appeals sweeping the country, more than ten years before such a backlash emerged in full force. Democrats’ core economic strategists made no secret of what they thought was driving these risks: the embrace by both parties of a neoliberal economic model in the last two decades of the twentieth century. The acknowledgment of this risk motivated attempts under the administrations of both Obama and Biden to mitigate the consequences of the new economy for its victims — to compensate the “losers,” as Obama put it. What happened next may appear to Zakaria et al. as a long process of Democratic candidates shuffling to the left, but that is a dramatic overstatement of what actually occurred. And both administrations’ efforts were hamstrung by their rock-solid commitment to securing the blessing of capital, as well as that of their own party’s more conservative members, for any expansion of the social safety net.

This underscores an important point. For all the talk of the Democrats’ alleged “leftward ho!” spirit since 2000, the doyens of the party’s economic team — from Roger Altman to Robert Rubin and (with the partial exception of the Biden presidency) Larry Summers — have consistently been each Democratic administration’s most loyal defenders in the corporate world.

To what does the party owe the steadfast support of these leading figures from Wall Street and corporate America? There was in fact never any significant left break with the basic premises of the Clinton administration by Democratic leaders: the goal of balancing the budget, a defense of free trade, and a relentless focus on retaining “business confidence.” Each new administration has made modifications to the playbook written during the party’s 1980s right turn that was first enacted in the ’90s. But none has dared to question its basic logic. Each Democratic administration has pledged obeisance to the party’s enthusiastic (and sometimes, at least temporarily, one-sided) search for a partnership with the business world. No Democratic administration has countenanced a direct confrontation with it. And — rhetoric and platform planks notwithstanding — no Democratic administration has, in recent decades, delivered on either a substantial rewriting of labor law in favor of unions or any expansion of public health insurance that directly challenges the for-profit health care model. It’s of no small significance that, despite serving at the helm of the “most pro-labor administration in US history,” it was Kamala Harris and not her opponent who was showered with money from the rich and well-connected.

And that might be the most damning conclusion one can deliver about the Biden administration and its efforts to revive the New Deal Democratic Party. After four years in power, Biden’s top deputy and chosen successor was the beneficiary of not only an even greater proportion of middle-class votes but also an enormous cash advantage over her Republican opponent — all while working-class voters continued to gravitate away from her party. Biden’s presidency — whatever one makes of its intentions — marked the death of the New Deal Democratic Party, not its rebirth.

Prospects

What, then, does the future hold?

First, the Democrats’ repeated failures to seriously address mounting economic grievances have left the door open for a very different, Trumpian solution. Donald Trump’s answer — protectionism, restricting immigration, cutting taxes, and stripping regulations — seemed to many “losers” in the new economy to be the only game in town for addressing their concerns, and unlike the Democrats’ promises, Trump’s had the seeming virtue of being realizable, as his first administration demonstrated. This is not to say that Trump’s agenda presents a real solution to working-class grievances with the new economy any more than the Democrats’ mix of free trade and a slightly stronger safety net do. But in the 2024 election at least, Trump had the unfair advantage of having been blessed with what many believe was a roaring economy in his first term.

Second, dealignment does not mean that the Republican Party will naturally succeed the Democrats as the home of American workers. It is far more plausible that both parties will remain unambiguously the home of different sections of the middle class — the Democrats of professionals and affluent college-educated voters, the GOP of socially reactionary middle-class voters, economically conservative small business owners, and middle-management types. A working class that has dealigned from the Democratic Party does not have to realign with the GOP. It can languish in the gulf between the two, swinging from one to the other in protest of the incumbent party.

Third, class dealignment should not lead those on the Left down the fantasy path of believing that Democrats’ recent defeats will inspire a new, more robust rethinking of the party’s purpose and its base — at least not one that will point in a progressive direction. Some on the Left hang their hopes for changing the party on its 2024 loss. They postulate that, driven by their defeat, Democrats will come to appreciate the need to build back (even) better next time, redoubling the Biden administration’s efforts at winning back working-class voters, if only to make themselves electorally viable again.

But does class dealignment really mean that the Democrats, having lost their hold on the country’s working class, are in danger of becoming a minority party? Is there good reason to hope that 2024 will inspire a major policy rethink in the party’s inner circle, with beneficial results for progressive priorities? The short answer to both questions is almost certainly no. This is because such a turn, which would require a much more antagonistic relationship to capital, would constitute a profound break with the party’s recent past. There is no reason to believe such a break is on its way, or even that it could prevail against a business base and donor class that would surely resist it if it were attempted. The 2024 election results hardly spell electoral doom for Democrats. Given the historic unpopularity of their incumbent president, the bungled and last-minute handoff of power to Kamala Harris, and the crippling bout of inflation that gripped the country under Joe Biden’s watch, Democrats lost by surprisingly slim margins in both the presidential election and the battle to control the House. Isn’t it reasonable to think — as many in the party do — that without making much in the way of changes, 2026 and 2028 can be a 2018 and 2020 redux?

Dealignment, in other words, is not synonymous with electoral crisis for the Democratic Party. To those who have hopes that the Democratic Party is a truly progressive party at heart, swapping working-class voters for middle-class voters appears to be a bug. But for those in the party with actual power, it’s a feature.

Finally, dating the origin of class dealignment to the 1990s and the Democrats’ new economic strategy has important implications for the labor left. On the one hand, with a clearer appreciation of the origin and unfolding of class dealignment, the labor left should take renewed solace in the idea that its hopes for building a working-class majority for redistribution and for defending the gains in civil rights and cultural progress are not baseless. The Democratic Party’s rightward shift on economic questions, its embrace and amplification of class dealignment, and its failure to correct course in any significant way are responsible for the loss of workers’ support. Workers did not swing disproportionately away from Democrats because of the special appeal of racially reactionary politics. Nor did they vote against Democrats in the last few years out of what Chait called a “bracing” “diffidence” in the face of the party’s overly generous appeals to their interests. This means that the labor left’s case for the centrality of class politics and the working class in building a better world is as strong as ever.

On the other hand, a clearer appreciation of class dealignment’s causes reveals serious challenges for the labor left’s current political strategy. To date, many have hung their hopes on working within the Democratic Party and using primaries to advance the labor left’s toehold in Congress. But the outflow of working-class voters from the Democratic Party’s core supporter base and their replacement with middle-class voters will only continue to ratchet up the difficulties facing pro-labor, left-wing forces in the party’s primary elections. The most concerning fact of all is the Democrats’ loss of support among Latino workers in the last four years. Latino working-class voters’ support for Bernie Sanders in 2020 was one of the most encouraging developments of that year, suggesting that Sanders’s core base could be expanded beyond college-educated young people. But as his 2020 campaign also demonstrated, mobilizing millions of disengaged voters to participate in primaries is a dubious proposition. Once lost to the party, it becomes harder and harder to regain those voters’ active support and interest in Democrats’ internal affairs. The fact that the Sanders wing, following the defeat of representatives Cori Bush and Jamaal Bowman in party primaries in 2024, has exited the Biden years with fewer rather than more members in its tiny congressional toehold is even more reason to doubt the viability of the labor left’s uncomfortable marriage of convenience with the Democratic Party.

These challenges must be the focus of the labor left’s energies in the months and years to come. It goes without saying that workplace organizing remains a key task. But something fundamental must also change in the labor left’s electoral orientation. At the very least, a much more confrontational approach toward a party that has actively encouraged class dealignment is needed. Sanders himself has hinted at the possibility of such a change in tack. As he rightly put it in his postelection autopsy: “Will the big money interests and well-paid consultants who control the Democratic Party learn any real lessons from this disastrous campaign? . . . Probably not.” If the 2024 election puts the labor left on a more aggressive course to challenge the party, it could yet have some positive long-term effects. We can work toward that change. Any ambitions for developing a robust response to the ongoing climate catastrophe, rebuilding an economy that guarantees good work and social support for all, securing racial justice and the defense of civil rights and personal freedoms, and forging a more peaceful and cooperative world order — to say nothing of loftier aspirations for winning a democratic socialist future — rest on finding a more independent and confrontational approach to a Democratic Party that has fully shorn itself of its New Deal heritage.