Remembering the Revolutionary Cinema of Pino Solanas

Argentine filmmaker Fernando “Pino” Solanas was the father of Third Cinema, the left-wing Latin American filmmaking movement of the 1960s and ’70s. In this 2016 interview with Pablo Iglesias, Solanas talks about his life, his work, and his politics.

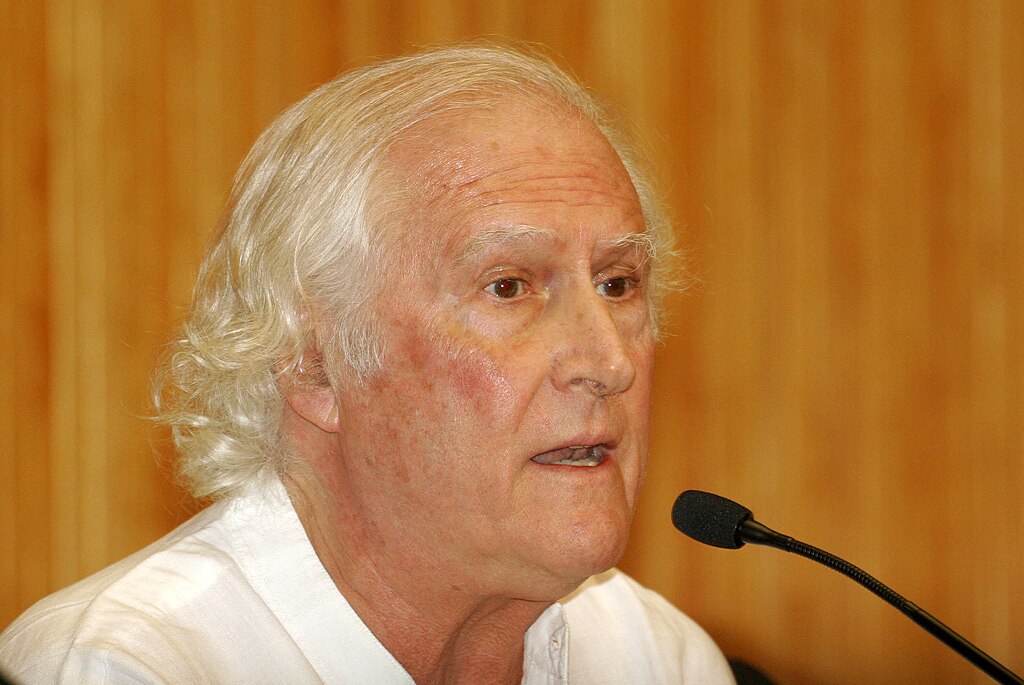

Fernando “Pino” Solanas at the 2008 Guadalajara Film Festival. (Wikimedia Commons)

- Interview by

- Pablo Iglesias

Fernando “Pino” Solanas was a giant of world cinema and arguably Latin America’s most celebrated filmmaker of the twentieth century. His passing on November 6, 2020 was mourned by the international film community and by countless activists on the Latin American left, many of whom had experienced their first political awakening as youths watching “Pino’s” radical agitprop films.

Director of over twenty feature films and documentaries, a lifelong political activist, and occasional left-wing politician, Solanas will forever be remembered as the father of Third Cinema, the radical Latin American filmmaking movement of the 1960s and ’70s that sought to turn the camera into a weapon of the revolution.

Pino was born on February 16, 1936, in the well-to-do neighborhood of Olivos in the greater Buenos Aires metropolitan area. Like many other middle-class youth in Argentina, Pino came of age politically during the years of the so-called Peronist Resistance — the period following the populist leader’s forced exile in 1955 that saw increased radicalization among Juan Domingo Perón’s working-class base.

Inspired by that radicalization and by the resistance to the military dictatorship of Juan Carlos Onganía, a younger generation of the traditionally anti-Peronist middle class began to gravitate in the late 1960s toward Peronism. Solanas was among them, and he like many others believed that the nationalist-populist movement could be steered in a more revolutionary — even socialist — direction. Several groups, such as the Montoneros, even engaged in guerrilla warfare in the name of Perón.

Solanas’s contribution to the revolution was always with his camera. His first major film, La hora de las hornos (The Hour of the Furnaces), was the ultimate ’60s cultural artifact: equal parts political agitation and bold formal experimentation, its rapid-fire montage of Frantz Fanon quotes and Vietnam War footage called on viewers to become historical agents and complete the film’s meaning with their own political interpretation. Another revolutionary Argentine filmmaker, Raymundo Gleyzer, called this kind of filmmaking “counter-information,” since it was supposed to throttle the viewer and draw them out of their role as passive consumerist spectators.

Solanas would go on to become a prolific filmmaker and explore more conventional formats. From highly praised dramas like Tangos, el exilio de Gardel (Tangos, the Exile of Gardel) and Sur (The South) to politically charged documentaries like Memoria del saqueo (Social Genocide), which portrays the social toll of economic liberalism during Argentina’s democratic transition, Solanas would continue to produce impactful films, capturing his country’s social and political turmoil right up until to his death at the age of eighty-four.

In this interview, conducted in 2016 by Pablo Iglesias for the Spanish television program Otra Vuelta de Tuerka, Solanas talks at length about his lifelong political commitments, the inspiration he drew from controversial populist leader Juan Domingo Perón, and about how he tried through his life’s work to capture the worldview of the Global South and raise up the cause of the oppressed. The transcript has been lightly edited for clarity and brevity.

Your childhood in Argentina was deeply affected by Perón’s rise to power. What memories do you have of that period?

I came from a bourgeois, middle-class household. My father was a doctor. I had distant relatives on my mother’s side dating back to Argentina’s War of Independence, but basically I came from a typical middle-class, Catholic, apolitical background.

To answer your question, Perón put fear into the hearts of Argentina’s oligarchy. And my family, as part of the bourgeoisie, felt that fear as well.

You have to remember something about Argentina at that time: prior to Perón the country was essentially governed by an aristocracy, and everyone else lived in a condition of near servitude. The entire 1930s was a decade marked by colonial submission to the British, and what they were calling democracy back then was a complete farce. So in that sense, the rise of Perón was simply a reaction against oligarchy and colonial dependence.

Those were extraordinary years in Argentina. When Perón came to power we began to see the world differently: there was the North with its outlook and the South with its own worldview.

I’d like to hear about how you began your career in film. I understand you were a complete autodidact and that you studied film by taking notes in movie theaters and sneaking onto film sets.

I loved film, but as a teenager I was even more interested in music. Early on, I dreamed of being a composer or orchestra conductor, but the problem was that I didn’t have the musical gift. Still, I wanted to write a great opera.

I decided instead to pursue that same dream in cinema — to make operatic cinema. I wanted to combine poetry, the time-based arts, the musical and dramatic arts.

The problem was that there was no film school in Argentina at the time, so I enrolled in the National School of Theater. It was only later when I began work in advertising that I received my true film education.

I wanted to make “pure art,” but I got my start in film working with advertising, the lowest form of cultural expression. I worked selling products and writing jingles — I must have composed over two thousand jingles and nearly eight hundred commercials spots. If nothing else, I developed an incredible knack as a salesman.

Your first film was a major landmark for an entire generation in Latin America, and in Europe as well. La hora de los hornos deals with colonialism, subalternity, and the peripheral condition of Latin America. It was also filmed under semi-clandestine circumstances.

I was both director and producer of the film. While I was directing, I was also making commercials for large advertising firms to finance production of La hora de los hornos.

That film broke the mold for its time, as you point out. You have to remember, it was shot during the Juan Carlos Onganía dictatorship in Argentina, and it was impossible to even screen the film. You might ask: Why make a film if you’re not going to be able to screen it?

Fortunately, we had developed a workaround. We were already projecting banned films in neighborhoods, usually at private residences or social halls. Precisely because the films were banned, everyone flocked to see them.

The most interesting part of those screenings was that, since we were projecting with 16mm film, every forty-five or fifty minutes the film reel would come to an end. Someone had to turn on the light and switch reels. And during the three or four minutes it took to do that, the audience began to talk about what they had been watching. They started to connect the scenes they had seen with their own lived reality. That was the birth of the idea of the “film-act.”

La hora de los hornos drew on that experience. The film was conceived in three parts. The first was a piece of straight agitprop. But the second and third parts were divided into thirty-five-to-forty-minute segments, where after each segment a political debate was supposed to take place.

The basic idea behind film was that the agent of history would have their own experience projected onto the screen, provoking within them some reaction that would then lead them to discuss and analyze their situation more deeply.

Shortly after La hora de los hornos, you and Octavio Getino published your manifesto “Toward a Third Cinema” and founded the Liberation Film Group. I remember when I taught political cinema at the university, my students couldn’t make heads or tails of that kind of politically committed filmmaking. What did it mean to you to be a committed artist-intellectual back then?

Obviously, we were fully committed to the cause. When you make a film like La hora de los hornos in Argentina at that time, the best you can hope for is to be thrown in jail — because the alternative is the dictatorship throws you in a ditch and puts a bullet in the back of your head. We were fully aware of the risks we were taking and accepted them. Artistic creation has its risks, and political creation does too.

But the real challenge was to create an alternative circuit for film projections. At its height, the system we created boasted more than seventy different teams responsible for film screenings. The Liberation Film Group was meant to be an organization among many others, all working together in a mass movement to defeat the dictatorship. Our role was to provide those other organizations with films — sometimes our own, sometimes others — so long as those groups were with us in the fight against the dictatorship.

We didn’t have the resources to make enough copies of the films for all the organizations wanting to hold screenings. But we had comrades working in film laboratories that would do it for us. By the end of the dictatorship, we had established something truly incredible: a vast, complex network for distributing and screening films. By 1970 we were showing films in public squares for two or three thousand people.

Third Cinema was a global phenomenon. There was Cinema Novo in Brazil, Jorge Sanjinés led a similar movement in Bolivia, and there was Tomás Gutiérrez Alea in Cuba.

I wanted to ask you to comment on a particular scene from Gutiérrez’s Memories of Underdevelopment, where a group of white intellectuals are discussing literature and colonialism while being waited on by black attendants. What did that scene mean, as a provocation or founding gesture of Third Cinema?

That scene is truly remarkable. Coincidentally, La hora de los hornos was first screened at the Pesaro Film Festival alongside Memories of Underdevelopment.

People saw scenes like the one you mention and made the mistake of thinking that the films of Third Cinema were an entirely separate film category: “activist documentaries,” they were called at the time. That was a huge misunderstanding. Third Cinema was not based on cinematographic categories. It was based on cultural and ideological categories.

The idea was to break with Hollywood’s conception of what a film should be or, if you prefer, the bourgeois, capitalist conception of film. Because that system had its own internal categories that we wanted to move away from. Third Cinema took as its starting point the decolonial conception of the world proper to the Latin American people.

When I say “the decolonial,” I’m referring to the effort to overturn the main legacy of the colonial experience: dependency. Dependency means that you’re burdened with an enormous inferiority complex. In that era — and not too much has changed — being successful meant making it big in Europe or the United States.

The challenge was to decolonize and produce an authentic form of creation that would belong to Latin America. Where did those forms come from? In part, from the mysterious experience of unique regional temporalities, popular cultures, and popular music, perhaps the most authentically popular of all cultural forms.

I made my films with those materials, anywhere where popular rhythm could be found and where the continent’s people had a particular way of inhabiting time. We don’t inhabit time in the same way as a Frenchman or a Swede, you know.

Those things are very difficult to render in aesthetic terms. I’m thinking of someone like Sanjinés in Bolivia, who was always trying to capture an Aymara or Quechua aesthetic.

At the same time, it is incredibly difficult to compete in aesthetic terms with the strength of “First Cinema.” The latter is capable of completely shaping the spectator’s visual perspective, while Third Cinema or political cinema almost requires special training; it runs the risk of becoming exclusively for doctoral students, one could say.

That’s a big issue. But I would say that our best films were also the most successful. And we made our share of bad films! We should remember: the best politics can’t save you from making bad art.

I made Tangos, el exilio de Gardel toward the end of 1983, between the end of the dictatorship in Argentina and the beginning of the democratic transition. The idea behind that film was to break with the entire schema of cause and effect typical of American cinema, where everything has to be in the service of the main plot. I always hated that framework and felt that in reality we live multiple, different adventures: work, love, family, dreams, metaphysics, and so on.

Argentine critics were baffled when they say the film. None of them understood it. That being the case, the film played in theaters for sixteen weeks straight and became an iconic film for an entire generation of youths.

I wanted to ask you about your meeting with Perón in Madrid in 1971. Perón left you with a list of mission tasks that you were meant to pass along to other Peronists. That meeting was also remarkable because you were there with Perón, filming him in Madrid during the late Francoist years.

Perón took notice of La hora de los hornos: it was one of the first films to offer critical support of his government. He liked it so much that he agreed to let us film him while he discussed his political career. But it took us three years to make the film — the whole situation in Spain with [Francisco] Franco was very complicated.

The two films that came out of that encounter were of enormous importance. They were screened thousands of times in Argentina and became an important weapon in the final battle that eventually overthrew the dictatorship of [Alejandro Agustín] Lanusse.

That was in 1971, and that same year the entire political leadership of Argentina, Peronist or not, traveled to Madrid. There, Perón was calling to organize a united front. His idea was that the front would include even those parties that had collaborated in his ouster. His rationale was that it was better to neutralize them within the front than let them go over to the side of the dictatorship.

He explained his logic for the front in no uncertain terms: you can either choose neocolonialism or liberation. And Perón did in fact have his own theories about what those two terms meant.

During that same period Perón was developing his Triennial Plan. If someone today in Argentina were to implement that policy, they might as well be called Leon Trotsky: nationalization of bank deposits, nationalization of foreign trade, nationalization of the Central Bank.

Who was Perón, you might ask? Perón represents a line of continuity with Latin America’s revolutionary independence leaders. Some people didn’t, and still don’t, understand his nationalism: it fundamentally came down to recognizing the difference between the nationalism of the oppressed nations and that of the oppressors.

What is perhaps hardest for people to understand is that we held Perón in very high esteem as a political theoretician. Our European comrades especially could never make sense of that. But the European left should remember back to 1945, when the Allies arrived in Paris. That same week France was bombarding Algiers, then Indochina, Africa, and so on.

Mao [Zedong], [Gamal Abdel] Nasser, and [Jawaharlal] Nehru hadn’t come to power yet. It was Perón alone at that time denouncing what he called the “two imperialisms”: the Soviets and the Americans. The difference between individualist capitalism in the West and state capitalism in the Soviet Union was not so big in our eyes. Both oppressed their people, we felt.

What I’m describing is essentially Perón’s “third position,” which is about much more than avoiding the influence of one or another side [in the Cold War]. Argentina was the first country to put into practice universal collective labor agreements. The 1949 constitution adopted under Perón was the most progressive in existence in the Third World. It stated explicitly that private capital has to serve a social function. It would be hard to overstate how advanced that constitution was; it raised many of the same issues that would later be taken up by the United Nations. It also called for the nationalization of public services and said that all natural resources in the energy sector were to be the inalienable property of the nation.

The “open veins of Latin America” were bleeding especially badly in the 1970s as military dictatorships spread across the region. You were particularly affected during that period: your life was under threat, you were nearly kidnapped, and eventually you went into exile. What was that chapter of your life like, when you spent time in Spain and eventually settled in Paris?

I remember that period as a time of grieving. But to be honest, I had been living as a sort of exile for almost my entire life. In Argentina I was always living under military dictatorships or nominal democracies with harsh censorship.

When I was forced to leave Argentina in 1976, I knew that I had a dark period ahead of me. You lose all sense of time — there’s no return date when you are in exile. That can drive you crazy.

I tried to go to Venezuela, but they wouldn’t grant me entry. Eventually, after forty-eight hours in the airport I continued on to Madrid. I spent months there, and later in Barcelona.

Fortunately, La hora de los hornos had developed a following in Europe, and I had friends in Italy, France, and other countries. In France, they managed to get me a resident’s card, and with that I could eventually bring my family to Paris.

Despite the sadness of those years, I managed to produce several screenplays. I even wrote an extraordinary screenplay about Spain that, unfortunately, I never had the opportunity to produce: El Viento del Pueblo.

As a teenager I was a great lover of poetry, and among others, I adored the Spanish poet Miguel Hernández. Even before going into exile, I had the idea to do something with Hernández, and with the experience of exile I felt an even stronger kinship: like him, I found myself being persecuted, forced to wander the world, just like Hernández after the Spanish Civil War. El Viento del Pueblo was meant to be a film based on Hernández.

You returned to Argentina after the dictatorship in 1988 and made Sur, which was a huge success. There’s a fantastic scene in the film where someone says to a military general: “You don’t know what the South is because you’re from the North.” What exactly do you mean by the “the South”?

“The South” is a cultural category. It’s an emergent civilization recognized by great thinkers and historians the world over. Here in Latin America, it means creating an independent nation where we can realize a socialist utopia with a human face. The utopia of freedom and social justice, of a land free of war and any type of contamination (agrochemicals especially).

A dream of “Southness”: that’s the basic idea. We are, if don’t mind the term, “Suristas.” We see the world differently, through a decolonial lens, and I think that perspective is unique to us in Latin America.

You made La Nube, your last feature-length film, in 1998. That film, which offers a devastating critique of the Argentine middle class, brought you a lot of criticism. How would you respond to that criticism today?

The price I paid for that film was that I suffered a stroke. That’s why it was my final feature film: cinema can kill you. La Nube and El Viaje, the film before it, were both made during the 1990s, at the height of Argentina’s neoliberal era.

And it was during that period that you became one of the leading critical voices opposed to neoliberal president Carlos Menem.

Argentina has had five periods of democratic governance. The first began with the first constitution in 1853. The second period is bookended on one side by the first election by universal suffrage, which brought the Radical Party and Hipólito Yrigoyen to power in 1916. That was, if you will, the first emergence of the middle sectors of Argentine society.

The third period is the struggle for social rights: the first Peronist period beginning in 1946, consecrated with a new constitution. 1957 was the year of constitutional reform, marking the beginning of a developmentalist phase in Argentina under President Arturo Frondizi. The next decades, from the 1960s to the ’80s, saw a rotating cast of military dictatorships.

In 1989, then president Raúl Alfonsin resigned amid a hyperinflationary spiral. His resignation opened the door to Menem, a typical puppet for the corporations and an advocate of the Washington Consensus. He implemented the consensus while also speaking in the name of Peronism — even though his government completely reversed every significant legacy of Perón.

The government of Menem, the fifth period of democratic governance, was Argentina’s neoliberal period in its most openly neocolonial expression. No other administration impoverished Argentina like that of Menem.

From the dictatorship until the present, Argentina has paid over $450 billion in debt. That’s the entire national GDP dedicated to debt servicing. Under Menem that only grew worse. Like no other government, Menem auctioned off all of the nation’s assets. He sold off every means that Argentina had to keep itself afloat financially.

For seventy years, Argentina’s energy policy had been focused on self-sufficiency, using fossil fuels to finance national industry and public works. All of a sudden, with Menem, that came to an end.

You made two important films about the neoliberal 1990s in Argentina: La dignidad de los nadies and Memoria del saqueo.

Those two documentaries are the first in a saga of what will eventually be ten documentaries. I’m currently working to finish the ninth, a film about agrochemicals and the villages in Argentina that have been poisoned by their use. GMOs and the agrochemical industry are rampant in the Argentine agricultural sector, which is in turn responsible for providing foreign reserves for the Argentine treasury. This is a huge problem, and it will be a long time before we’re free of that issue.

Why did I ultimately opt to pursue documentary films rather than features? It was not because I didn’t have the budget to make feature films, although that has been an issue. I did it because the level of disinformation in the world, and in Argentina, is astonishing.

The [Néstor and Cristina] Kirchner administrations did pass a very well-intentioned media law. But like most of the Kirchners’ projects, it was tainted. You can’t have a democratic, pluralist control of the audio-visual sphere — everything from politics and news to entertainment and sports — without also guaranteeing some autonomy from state control.

How would you assess the Kirchners’ legacy?

You have to remember something about Nestór and Cristina: they did not emerge from the movement against Menem in the 1990s or from the earlier human rights movement.

You also have to draw a distinction between Nestór and Cristina. Nestór had a good head for politics. He was a good administrator of state affairs, and he passed certain extraordinary measures under his government. He was instrumental in the famous gathering to say no to the Free Trade Area of the Americas agreement — to refuse to join with George W. Bush in a regional free trade agreement. He was also an important driving force behind “South” oriented projects: the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR), the Southern Common Market (MERCOSUR), and so on.

But that was also an exceptional period in Argentine history that depended on commodity prices; Argentina drew in $150 billion during the period. That money was not used to seize control of the foundations of the economy and move toward independence. Even though the Kirchner administrations had congressional majorities, they failed on almost every count to strike down Menem’s laws.

A final question: What is one film that was pivotal for you?

One of the most important directors for me personally was Gillo Pontecorvo. I would have loved to have made the The Battle of Algiers. Gillo and I eventually became great friends, and he told me one time that he wished he could have made La hora de los hornos.