NBA Players Wanted Their Rights as Workers. Owners Were Standing in the Way.

NBA players are well-paid today, but it wasn’t always so. As a new labor history of the league shows, pro basketball players had to unionize and threaten strikes to get out from under the thumb of owners and win a bigger piece of the financial pie.

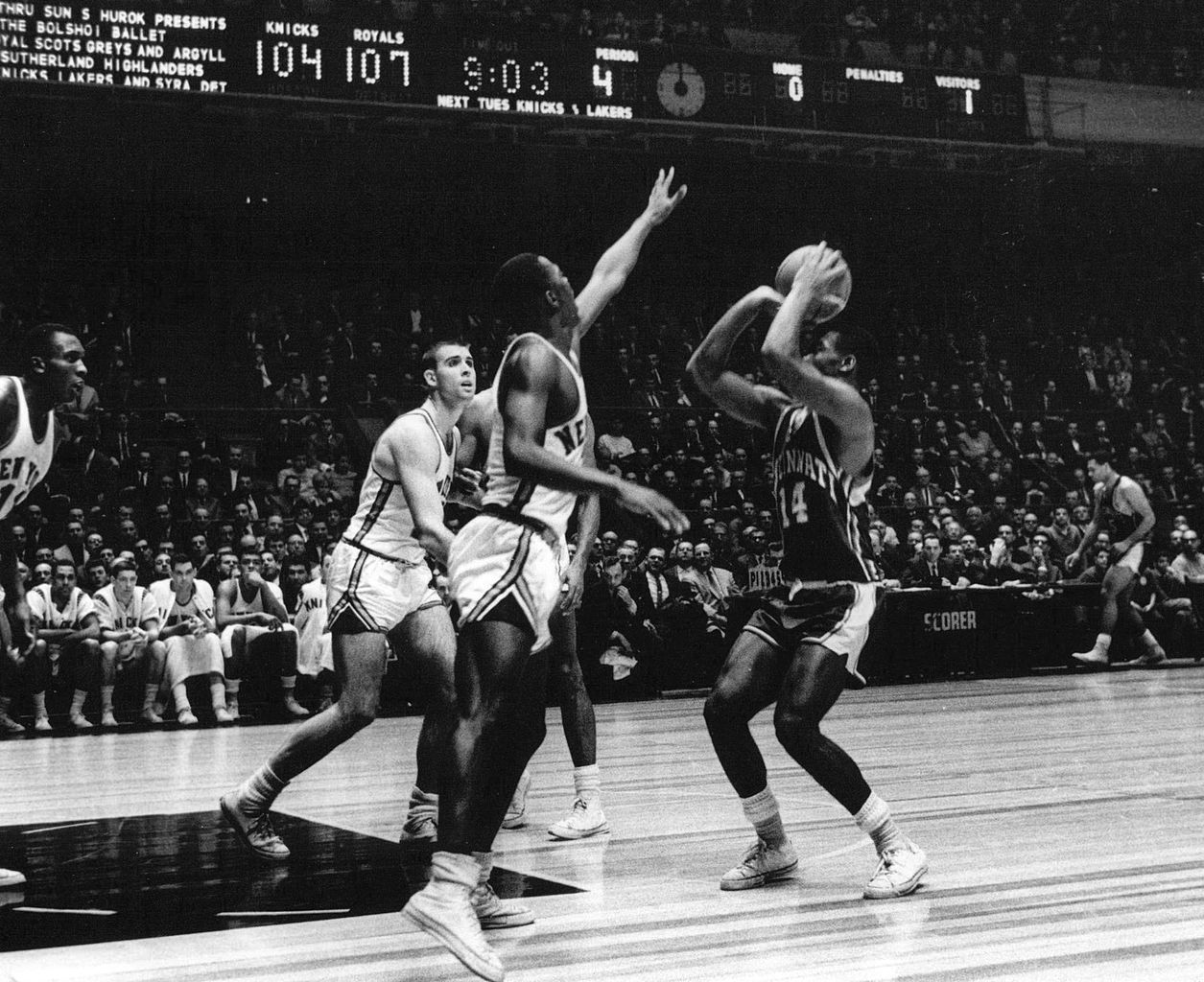

Oscar Robertson (with ball) playing for the Cincinnati Royals in 1964. (Sport Magazine Archives via Wikimedia Commons)

- Interview by

- Michael Arria

In 1983, just weeks after Ronald Reagan broke the air traffic controllers’ strike, the National Basketball Players Association (NBPA) threatened a work stoppage of its own. That move ultimately proved successful, as the National Basketball Association (NBA) became the first US sports league to adopt a revenue-sharing plan, guaranteeing players a 53 percent slice of the financial pie. In exchange, the owners got their coveted salary cap, which placed a ceiling on player pay.

These high-stakes negotiations began in the early 1980s, but in his recent book The Cap: How Larry Fleisher and David Stern Built the Modern NBA, labor lawyer Joshua Mendelsohn documents how the labor battles of the preceding decades helped set the stage for the multibillion-dollar league of today.

The result is a riveting work of labor history, full of memorable characters who are also Basketball Hall of Famers: Fleisher, Stern, Bob Cousy, and Oscar Robertson, among them.

Jacobin contributor Michael Arria spoke with Mendelsohn about his book and why players, not owners, should have our allegiance.

Your book covers a time when the late David Stern was serving as the NBA’s general counsel. I think most basketball fans know who Stern was, as he went on to become commissioner of the league and was a larger-than-life character who certainly didn’t shy away from the spotlight. However, I’d be surprised if many people know who Larry Fleisher was. Who was Fleisher, and why was he important?

I didn’t know who he was either to be honest with you. I’m a labor lawyer, I love this stuff, and I didn’t know who he was.

He was a lawyer and an accountant. He got called in by some of the [Boston] Celtics in the early ’60s to help them run a union. He was a tax lawyer; he wasn’t a union guy. He was very, very smart, and he built up this organization over twenty years. He led the walkout in 1964, the NBA almost strike in 1967, and the Oscar Robertson suit [which helped establish free agency]. Each one of these things were real steps in building economic freedom for NBA players, and they were all led by Larry Fleisher.

My view is that he approached the NBA like it was a tax code. He was trying to find loopholes; he was trying to expand things. He built the union muscle over his time as a union leader, but that’s not where he came from. So I think his ability to be creative and think outside the box made him different. For a whole generation of players, he did an incredible job. The leadership of the union — players like Tommy Heinsohn, Paul Silas, Bob Lanier — these guys were amazing.

So, he did an amazing job at being economically forward-thinking, but also building a strong labor organization that was really successful. But he’s largely forgotten. One of the goals of my book was to tell his story. This guy existed and beat the pants off the owners for a long time. He was an institution in the NBA for twenty-five years, and thank God he was.

Your book documents a lot of the NBA labor rights battles leading up to the ’80s. I’m sure Jacobin readers would be interested to hear about what happened at the 1964 All-Star Game?

Fleisher takes over the union in 1961. He’s trying to get meetings with ownership, he’s trying to get the players a pension, and he’s getting blown off. The 1964 All-Star Game is approaching, and it’s going to be a big deal. The owner of the Celtics was a guy named Walter Brown, who was very well regarded by players and owners. It was the first All-Star Game that was going to be televised. The NBA was not nearly as popular as it is now, so this was the league’s big opportunity to shine.

The players decide they’re going to use the event to finally get a pension and establish real ground as a union. Heinsohn, the Celtics Hall of Famer, was the head of the union. He approaches Brown a couple weeks before the game and says, “Look, there’s going to be a problem. We’re going to push for this.” Heinsohn and Brown were very close, and Brown was furious that the players were going to take a stand on this. He basically told Heinsohn, “Why would you guys get a pension? I don’t get a pension. You should be happy with what you have.”

All the players come into Boston, where there’s a huge snowstorm, and they meet up. You look at the talent at this All-Star Game, and it’s incredible. It’s Wilt Chamberlain, Bill Russell, Oscar Robertson, Lenny Wilkens, Elgin Baylor, Jerry West, on and on — it’s everyone that people know from this era. They try to have a couple meetings throughout the day, but they continue to get blown off by ownership. Eventually the players say, “We’re not going to play unless we get what we want.”

The players are holed up in the dressing room at the old Boston Garden, and the owners are livid. The Lakers owner Bob Short has someone relay a message to the dressing room, which is basically, “Tell Elgin Baylor and Jerry West to get their asses on the court.” Baylor sends back a message: “Go tell Bob Short to fuck himself.”

A couple minutes before the game, the owners cave. They say, “We’re going to agree to this, but there’s paperwork that needs to be done.” The players say, “OK, we’ll take you at your word on this,” and that’s what they did. The players stuck together. It was an incredible act of courage at a time when the league wasn’t as strong as it is now, and when players didn’t have the same stability that they do now. Heinsohn had to work a job in the off-season. These players were really putting their livelihood on the line, but it worked. It set the stage for Fleisher and the players going forward. This was eight years before baseball went on strike. It’s a seminal moment.

This is a book about the NBA, but it also covers some of the labor fights in the National Football League (NFL) and Major League Baseball (MLB) that were happening around the same time. How did the labor unrest in the other US professional leagues impact the NBA’s economic situation?

They were all different, but connected. One of the things I wanted to show with the book was that collective bargaining is not episodic. It happens over a long period of time, and there are external factors the whole way.

Baseball, football, and basketball were all in a similar economic situation. They all fueled each other and impacted each other. They all rose around the same time in the late 1960s. You had Fleisher in the NBA, Marvin Miller in the MLB Players Association, and Ed Garvey in the NFL Players Association. They’re all getting ideas from one another. For instance, licensing stemmed from NFL players working on a bottle-cap deal — NBA players say they want to do that, and Miller ends up accomplishing it. They’re all working toward antitrust legislation and free agency.

When the NBA union started negotiating in 1982–83, there had just been a baseball strike in 1981 and a football strike in 1982. The NBA players are looking at that, and they’re preparing for a possible strike when they start their negotiations because they’ve seen it work. They’re all kind of working off each other.

Stern and the owners are pushing for salary moderations and cost cutting during these negotiations. Can you talk about the economic status of the NBA in the early ’80s?

Every negotiation in the history of sports involves the owners crying poverty. There are some instructive Fleisher quotes from the ’80s where he says that the league is consistently claiming to be broke no matter how many teams are in the league.

Larry O’Brien was the commissioner of the NBA. All of his documents are at Springfield College — and no one had really looked at them before, but I went over them for the book, and you can really see the internal economics of the league.

There are a couple issues at the time. The league’s TV deals are infinitely weaker than the other leagues’. Salaries rose quickly. They’re cycling through owners. You had ownerships that were really weak: Cleveland, San Diego. These teams were losing money, poorly run, and in danger of going under. There were real economic concerns.

The owners were trying to establish a framework for limiting salaries, but Stern was also pushing for revenue sharing because one of these teams might suddenly go out of business.

These negotiations drag on for a long time, and in 1983 the players actually set a strike date. How close did they come to striking, and what impact did that threat have?

Stern sends a memo about what he wants at the beginning of negotiations. He wants documentation of United Auto Workers negotiations, of givebacks. He wants to know how that’s been covered and what the arguments were in other labor cases.

The NBA tried to propose some salary limitations. The players said no. There were some legal machinations, and eventually it moved toward the players wanting a share of the revenue and wanting free agency. The NFL players had just gone on strike to get a percentage of gross [revenue] from the league.

The NBA players tell the league that they want to look at the league’s books to see if its economic situation is really as bad as it’s making it out to be. By 1982, Magic Johnson and Larry Bird are in the league, so the future looked bright. The NBA agrees. They start bargaining again.

The players say they’re going to go on strike in April. Why is that timing important? The playoffs are about to start, and that’s when the real money starts coming in. The owners go nuts at first. They refuse to meet with the players. The owner of the San Antonio Spurs is threatening to sue his players.

However, as the strike date approaches, they work out a deal that is basically the first salary cap. The players get 53 percent of the revenue that comes into the sport (including cable television) in exchange for a soft salary cap and some exceptions.

The Celtics owners were worried about retaining Bird: they got “The Larry Bird Exception,” which enabled them to resign a player for whatever they want. The Lakers were worried about Kareem Abdul-Jabbar retiring. They established an exception to sign someone to replace a player, even if the team goes over the cap. Guys like Ralph Sampson and Patrick Ewing were coming into the league, and teams wanted to be able to pay guys like that more so they could retain their young stars. All these things went into the agreement, and it was really the strike date that pushed it over the edge.

People look back now and think that this is how it was always going to be, like the idea of a salary cap comes down from God and there wasn’t this back-and-forth. That’s not true.

The NBA’s seven-year collective bargaining agreement expires after the 2023–24 season. A lot has changed in forty years, but some of the issues remain the same: salary cap smoothing, the revenues from TV deals, etc. How do the themes of your book connect to these current negotiations?

I think a lot of the fights in sports are fundamentally evergreen. There’s a pie. Players want as much of it as possible, and owners want to prevent them from getting that. Of course, many things have shifted, but in some ways it’s the same.

The scale might be a lot larger, but I think most people can understand what the fight is about. No one wears a jersey with an owner’s name on the back — fans wear the jerseys of players like LeBron James and Stephen Curry. It might not be the same thing as Heinsohn having to work two jobs, but players want to make sure they’re protected, and they’re looking out for future generations of players.