How Canadian Socialists Built a Working-Class Print Culture During the Great Depression

A half century before punk claimed ownership of zine culture, socialists and communists were radicalizing working-class culture through small publications. In Canada, during the turmoil of the Depression, print media was integral to the survival of the Left.

A cover of the Canadian Labor Defender from June 1932. (Library and Archives Canada

Imagine for a moment that you have in your hand a copy of a publication by a small but pugnacious leftist faction. The magazine is badly made and inconsistently printed. On top of the subscription price, its publishers are constantly asking you for money to help further the “cause.” Imagine, also, that there is a not-insignificant-chance that simply having that magazine in your home — or handing it to a friend — could put you at risk of arrest or police surveillance. You might, under these conditions, want to skip the newsstand entirely.

This hypothetical scenario was one faced by Canadian leftists in the 1930s seeking to support a growing wave of socialist and pro-worker publications across the country. When we think of the 1930s, we tend to imagine a decade of transience and depression. We think of men (usually men) on the move, seeking work or relief between dried-up farm fields and overwhelmed urban centers; we think less of abandoned families, deported immigrants, work camps, and jails.

These were, however, the issues that animated the independent leftist print industry of the 1930s. Quick and dirty magazines published by infighting leftists played an important role in keeping the socialist movement alive during the worst years of the Great Depression.

For many, the strong arm of the state made the conditions of poverty and precarity in the 1930s worse. Through the decade, local and national authorities found a new carceral zeal, establishing remote labor camps to contain unemployed men. Authorities redoubled efforts to enforce evictions and vagrancy laws, and they revived wartime statutes to detain and imprison Communists, labor organizers, and suspected foreign agitators on grounds of sedition. Both fear and protest swelled in the streets of Canadian cities, but first, they found voice in the newspapers, magazines, and pamphlets of a burgeoning radical left.

Labor and Left Print in Unvanquishable Number

The 1930s saw the launch of almost two hundred new labor and leftist papers in Canada — a 230 percent increase over the previous decade. Socialists published magazines in every major city across the country, in English and French, Yiddish, Finnish, and Ukrainian. These periodicals addressed famers, tradespeople, factory workers, housewives, and the unemployed — the working class in all its diversity.

By surveying these publications, we can track a shift in political consciousness. At the start of the decade, the newspapers tended to be organs for localized labor unions, or Communist-affiliated papers explicitly focused on building international red solidarity. However, left-wing publications were shaken by a raid on the offices of the Communist Party of Canada by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police in Toronto in 1931, and the subsequent imprisonment and heavily publicized trial of the party’s leadership. The incident reoriented many Canadian papers and magazines toward a renewed focus on the class conflict happening at home. The Left was energized, determined, and angry.

With renewed purpose, many groups organized around legal action against the excessive uses of state power. Canadian radicals targeted the anti-sedition and anti-terror laws in Section 98 of the Criminal Code — created in the wake of the Winnipeg General Strike — as well as immigration laws and the relief camp system ordered by the Department of National Defence. During this period, publications like the Canadian Labor Defender shifted away from commenting on American cases, like that of the Scottsboro Boys — nine black teenagers falsely accused of rape in Alabama — to focus on more local issues.

By 1932, the magazine devoted itself to publishing the transcripts of Canadian trials, fundraising for defense funds, and advancing a program of mutual aid and legal self-education among workers. The back pages of the Defender — and many of the other materials published by its parent organization, the Canadian Labor Defense League — show the growth of a dense network of aid societies, unions, women’s groups, and associations for people of color. These networks replicated, albeit in miniature, the more firmly entrenched social movement culture of the United States.

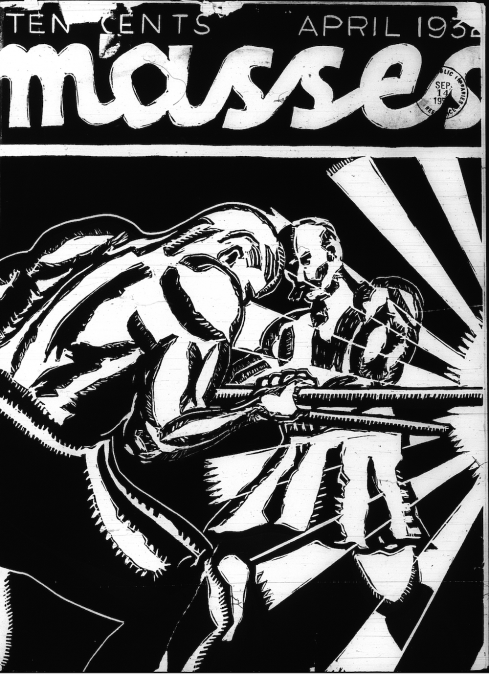

Masses and the Progressive Arts Club

By the middle of the decade, several leftist magazines established themselves within this growing print network. Titles like the Defender and The Worker secured modest monthly circulations but exhibited a sophisticated level of production. Their cleaner layouts and more extensive visuals broke up the previously dense columns of text.

However, the publication’s editors noted a weariness among their subscribers. Readers of the Defender begged for less complicated language and “lighter features” on culture, poetry, and art. Subscribers also wanted their socialist magazines to engage with issues similar to those discussed in popular print and media magazines. Hollywood movies, theatrical performance, modern novels, true crime, and gangster stories were all areas that readers of the early 1930s socialist press wanted to see discussed from a left-wing perspective. They also wanted more information about things happening in their own towns and cities, and to read about them in everyday language — not jargon-heavy leftist discourse.

Toronto’s Progressive Arts Club (PAC) was up to this task. From its founding in the fall of 1931, this group of young writers, artists, cartoonists, and dramatists set out to create explicitly revolutionary Canadian art. The PAC sought to appeal to workers and gave the cultural outputs of middle-class leftists a run for their money. By the following year, the PAC had established branches in Montreal, Vancouver, Winnipeg, and Halifax, and launched a new magazine, Masses.

Although it clearly emulated American publications like New Masses (particularly its output under editor Mike Gold), Masses’s voice was brash and sardonic, unlike anything else on offer from the Canadian left at the time. Many of its contributors, including Dorothy Livesay and A. E. Smith, would go on to play a significant role in Canada’s modernist literary scene.

The magazine’s reviews, commentary, and literary selections brought elements of politically conscious art and a taste of the avant-garde — growing in places like Moscow or Harlem — to its readers. Well before mainstream Canadian publications, Masses printed reviews of Soviet literature and poems by figures such as Langston Hughes, putting its own contributors into conversation with international movements.

Small Print Publics

Today, avowedly leftist cultural institutions are sparse in Canada. Masses is exemplary of what was so distinct about the radical small press in the 1930s. Part of the magazine’s image was the result of a self-mythologizing that had been with the publication since its inception. In the first article of its inaugural issue, its editors declared that the magazine “carries its credentials from the masses.” Subsequent issues left space for questioning these credentials and debating the worth of art in mass political struggle.

Masses opened its pages and political stances to debate, reframing conventional letters to the editor as “Criticism and Self-Criticism.” Accordingly, readers shot back with statements on the function of propaganda, as well as detailed — sometimes harsh — critiques of the cartoons, poetry, and general appearance of the publication. In turn, Masses, as well as the Defender, included reviews of other Canadian magazines and newspapers, sketching out a network of fellow travelers in print. These working-class publications shared contributors, an audience, and contempt for better-produced but ideologically soft middle-class publications.

The production quality of these early 1930s publications was not as strong as the political convictions of their authors. With their use of linocuts and photomontages, Masses and the Defender represent the high-water mark of production value. Other publications were more like mimeographed newsletters; issues stopped when the page limit was reached — a 1936 issue of The Leader, a communist newsletter out of Edmonton, terminates mid-sentence. Few of these publications lasted more than a couple of years. They would often disappear for months, reappearing with retooled styles and content. This intermittent issuance made it difficult to build a sustained readership.

By the second half of the decade, the Canadian left shifted toward a popular front or unity strategy. With a change of government, subsequent reforms around Section 98, and other laws protested against by the Left, the key organizing pillars of the radical movement disintegrated.

As fascism rose in Europe, domestic concerns faded into the distance. Would-be revolutionaries found common cause with their formerly sworn enemies, the social democrats. The founding of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation in 1932 also absorbed much of the energy of leftist radicals eager to influence the world around them.

These magazines, and countless other publications, are a record of a moment of surging class consciousness and public action by working-class people in Canada, infighting and all. But they also capture a cultural movement that struggled to grow beyond organizing by infusing revolutionary politics into artistic production and pop culture commentary.

Despite these limitations, the magazine presented its readers not just with a politics but with alternative ways of living within capitalist society. Instead of being an unemployed veteran, one could be a theater performer. Instead of being an underpaid shopgirl, one could be a poet. Instead of being a silent target of the law, one could learn how to go to court to defend oneself and others. In a time when many people found themselves reduced to a series of demographic markers and were oftentimes judged not worthy of relief and care, the ability to attain agency and creativity must have seemed transformative.

Activism on the Left asks a lot of its supporters. There are always more marches to join, more calls to make, more money to donate. Political parties and issue-oriented groups would do well to look beyond the campaign to see what kinds of lives their supporters are leading, and what kinds of needs are left unanswered. The integral part that 1930s labor print played in working-class culture is instructive for the current Left. Its lessons are clear: in the absence of art, culture, and creativity, there is no movement.