The Indian Radical Who Helped Found the Mexican Communist Party

Exiled from India, anti-colonial activist M. N. Roy charted a revolutionary course that took him everywhere from New York City to Mexico, where he helped found the Mexican Communist Party. His life was the epitome of socialist internationalism.

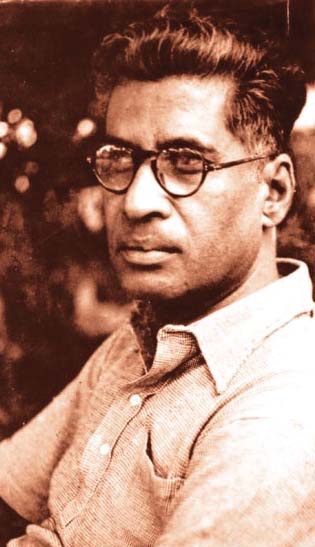

M. N. Roy with other delegates at the Second World Congress of the Communist International, Petrograd, 1920. (Wikimedia Commons)

When the Indian nationalist M. N. Roy entered a small Chinese restaurant in 1917’s Mexico City, he just intended to make a new friend in the strange land in which he was exiled. Instead, he would leave his lunch with aging Mexican socialist Adolfo Santibáñez with an idea, creating what would become the first Communist Party outside of Russia — an improbable twist of fate that would propel him to global fame.

Narendra Nath Bhattacharya, later known as M. N. Roy, was born on March 21, 1897, in the village of Arbelia near Calcutta. He joined the revolutionary independence organization Anushilan Samiti at the age of fourteen. Created by the Bengali barrister Pramanath Nath Mitra, the Samiti believed that a nationwide armed struggle was the only salient method to defeat the British Empire.

The outbreak of WWI made the Samiti look to Imperial Germany as a potential ally given their mutual enemy, the British. In 1914, the word came back; Germany was prepared to finance the revolution. Bhattacharya left for Japan in 1915 in what he assumed would be a short trip to meet the German consul for an, in hindsight, absurd plan. As he wrote decades later in his Memoirs, the Samiti had decided “to use German ships interned in a port at the northern tip of Sumatra, to storm the Andaman Islands, and free and arm the prisoners there,” and procure “several hundred rifles and other small arms” from Chinese smugglers to do so.

The trip was a failure; the Germans swiftly proclaimed they could not help fellow Indian nationalist Subhas Bose unless he went to Berlin, and Bhattacharya had to flee Japanese police investigating his activities. He would not see India again for the next sixteen years.

The revolutionary bounced from Japan to China, often travelling in disguise to throw pursuing colonial police off his trail. To make it to Berlin via the United States, Roy disguised himself as “Father Martin,” a theologian from French-controlled Pondicherry, and obtained a fake passport from his German contacts.

Bhattacharya arrived in San Francisco in the summer of 1916. He would slowly discard his suspicion of Marxism while conversing with American radicals, marry, and change his name to Manabendra Nath Roy.

This almost leisurely sojourn came to an abrupt halt once the United States joined WWI a year later. Now no longer a quirky Indian revolutionary but instead a German collaborator, Roy fled across the border to Mexico at a critical juncture in its history.

The constitution had just been passed by General Venustiano Carranza, the “victor” of the Mexican Revolution. His former allies, Emiliano Zapata and Pancho Villa, continued to challenge his regime.

Roy began writing for a local newspaper, El Pueblo, about the shared struggles of the non-Western world fighting for their liberty. His words reached a wide audience well-accustomed to the idea of revolution, from liberals such as Carranza to socialists like Santibáñez, with whom Roy founded the Socialist Workers Party in 1917.

But it was a revolution yet to come that would change the course of Roy’s life: that of the Bolsheviks. Roy recounts being “swept up in that electrified atmosphere” as his Mexican peers celebrated Vladimir Lenin’s triumph, and this euphoria combined with Roy’s newfound socialist leanings prompted him to formally change his party’s name in 1919 to the Mexican Communist Party (PCM).

Though the PCM failed to impact the Mexican political landscape, its establishment on the other side of the world drew the attention of the Bolsheviks. Mikhail Borodin soon arrived to personally invite Roy to the Comintern’s Second World Congress.

Roy reached Moscow in the summer of 1920, where he was personally received by Lenin, the “most unmitigated optimist” Roy had ever met. Lenin asked him to critique his draft on The National and Colonial Question and prepare his own thoughts for the upcoming congress.

Roy was largely irrelevant to the wider Indian debate on how independence should be achieved at this point. But now, a continent away, he suddenly found himself in the position to influence official Comintern policy on anti-colonial movements.

And shape it he did. Roy fundamentally opposed Lenin’s original assertion that Communist parties should ally with bourgeois-democratic liberation movements. Using the Indian National Congress (INC) as an example, Roy argued that India and other colonies had an absence of “reliable” nationalist movements; instead, socially conservative elites like Mahatma Gandhi ran the show, and would, in his estimation, switch allegiance to imperialist powers if it suited them. The Comintern, therefore, should instruct local Communist parties to “devote themselves exclusively to the organization of the broad popular masses for the struggle for the class interests of the latter.”

The most radical elements of Roy’s rejoinder — such as emphasizing that a worldwide revolution was only possible once colonialism was defeated — were quietly ignored. But by adopting a modified version of his proposals, the foundation for the Comintern and the future USSR’s policies were partially set by Roy.

Roy rapidly ascended the ranks of the Comintern, becoming a member of the Executive Committee in 1922 and secretary of the Chinese Commission four years later. This came to a halt after Joseph Stalin assumed control; spared the purges, Roy was merely expelled in December 1929.

He returned to India for the first time in sixteen years and was swiftly arrested by the British colonial state, denied trial, and sentenced to twelve years of hard labor, serving only six. This took its toll on Roy; he died in 1954, but not before remarrying and undergoing another profound shift in his political and philosophical outlook.

Disillusioned with Communism after his experiences in the Comintern and leery of the INC in a newly free India, Roy developed an alternative philosophy he called “radical humanism,” arguing that social progress ought to be measured by individual liberties.

Roy ultimately didn’t influence the Indian freedom struggle when he left for Japan in 1915. But what he did accomplish was nothing short of remarkable. From a young boy in the liberation struggle to a leading star in the Comintern, from a jaded nationalist to a committed Marxist and philosopher, from exile to heroic revolutionary returnee, M. N. Roy’s career was an astonishing one that took him around the world.

Like so many of his fellow underground Asian anti-colonial compatriots, like Ho Chi Minh or Tan Malaka, Roy’s own quest for independence intersected with other major political developments of the twentieth century — and ultimately reminds us of how truly global the anti-colonial freedom struggle really was.