Bob Marley’s Peace Gesture Supported Radical Change in Jamaica

An iconic 1978 image shows Bob Marley uniting left- and right-wing party leaders on stage, calling for a truce. Misread as apolitical, his gesture was actually meant to rescue a socialist political movement in danger.

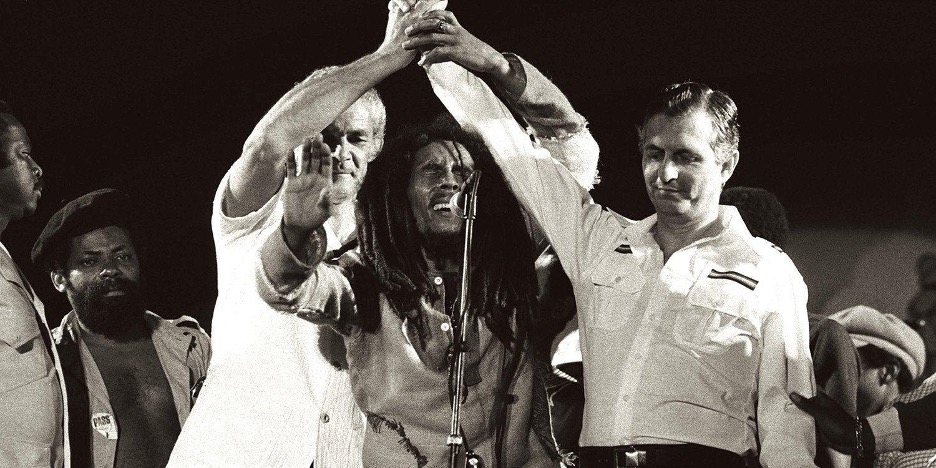

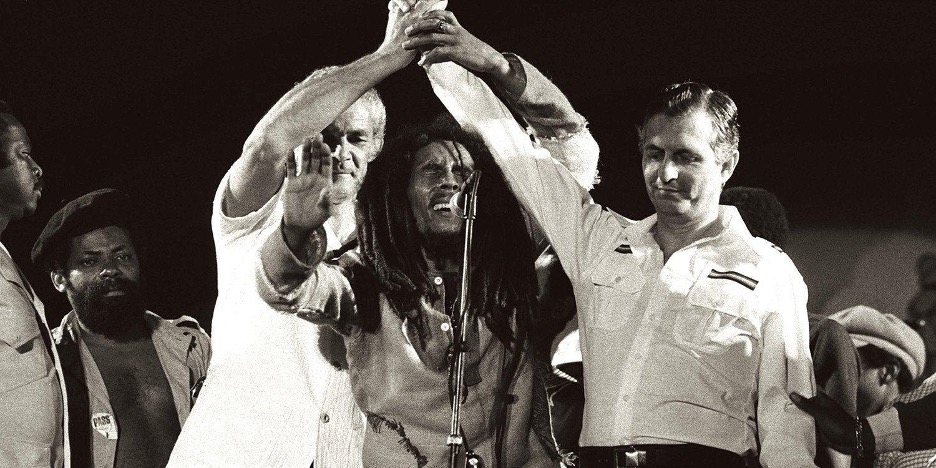

The iconic photograph of Bob Marley uniting the hands of Michael Manley and Edward Seaga at the One Love Peace Concert in Kingston, Jamaica, in 1978.

- Interview by

- Meagan Day

From 1974 to 1980, Jamaica was rife with political violence. Gangs linked to the country’s two parties, the democratic socialist People’s National Party (PNP) and the conservative Jamaican Labour Party (JLP), were locked in an urban paramilitary conflict that killed, injured, and displaced thousands of people.

In 1978, influenced by the Rastafarian message of unity, gang leaders agreed to peace talks. Out of this process came the One Love Peace Concert in Kingston, which brought together rival gang members, party officials, and the biggest names in reggae, including Bob Marley, who had himself been shot two years prior, most likely by a JLP gunman.

During his performance, Marley summoned onstage the party leaders, prime minister Michael Manley of the PNP and his opponent, Edward Seaga of the JLP, and clasped their hands in a sign of unity. Images of that moment are now iconic, in part because they seem to show Bob Marley as mainstream global culture imagines him: a peacemaker transcending all conflict, including politics.

But that interpretation is far too simple. With his gesture, Bob Marley was not trying to elide the political differences between the left-wing PNP and the right-wing JLP. Rather, he was attempting to rescue the hopes of the social movement that had carried the PNP to power six years earlier — a vision for a new Jamaica that the street violence, which many suspect was the result of a covert CIA destabilization program, threatened to destroy.

Africana studies scholar Brian Meeks was in attendance at the April 1978 One Love Peace Concert. Jacobin’s Meagan Day asked Meeks to unpack this iconic photograph, shown above, of Marley embracing Manley and Seaga. In order to properly understand what’s happening in this photo, says Meeks, we need to examine the evolution of Jamaican parties and social movements, the impact of foreign intervention on Jamaica’s prospects for change, and the role of reggae and Rastafari in Jamaican cultural and political life.

Brian Meeks is a professor of Africana studies at Brown University. He has published twelve books and edited collections on Caribbean politics, and he has written about Michael Manley’s democratic socialism for Jacobin. He is also the author of Paint the Town Red, a novel set amid the political violence in Kingston in the 1970s.

We have here in front of us a classic photo of Bob Marley uniting the hands of Michael Manley and Edward Seaga. In order to understand what’s actually going on in this photograph, we first have to cover a fair amount of political ground.

Let’s start with the two parties that each of these politicians represent, the People’s National Party (PNP) and the Jamaican Labor Party (JLP). Where did these parties come from, and what did they stand for?

In 1938, Jamaica had a labor rebellion against restrictive trade union laws that prevented proper organization. It was part of a Caribbean-wide labor rebellion, which brought the working class into the existing anti-colonial movement, as labor began to see independence as a possible avenue to ending exploitation.

In joining the anti-colonial movement, the working class joined the middle class, who felt they were excluded from the British colonial system, and who expected to inherit power from the British after independence. So the actors in this anti-colonial coalition did not want or anticipate the same things out of independence, but they all saw the need for British colonialism to end.

Norman Manley, Michael Manley’s father, was the leader of the People’s National Party, which was one of two parties that emerged after the labor rebellion of 1938. In the late colonial period, “national” had a far more progressive connotation than it did in Europe between the wars. The PNP was founded in the tradition of Fabian socialism, and was always the more left-wing of the two parties. But the PNP was never a traditional labor party. It was an alliance of the middle class, the working class, and the urban poor.

The other party, the Jamaican Labor Party (JLP), was far more conservative even though it carried the name “labor.” And though it was conservative, the JLP did in fact have significant standing among a section of the agricultural and urban working class. It had working people as its popular foundation while also enjoying significant support from business and the commercial sector. Suffice to say, while both parties relied on working-class support, Jamaica did not develop a traditional labor party in the years leading up to independence in 1962.

So, two Jamaican parties emerge in the late colonial period, one more progressive and the other more conservative, but both primarily focused on independence, and both supported by cross-class constituencies. How did Michael Manley come to lead the PNP, and how did the party change under him?

In 1968, there was another rebellion in Jamaica, this time inspired by the Jamaican government’s refusal to allow the university lecturer Walter Rodney back into the country after he left for a conference in Montreal. His exclusion led to a popular upheaval on the streets of Kingston.

The year 1968 has global significance. In the Caribbean, it’s considered the beginning of the black power movement, and the Rodney riots were the Jamaican expression of that. Simultaneously, the balance in Jamaica shifted away from the first postcolonial government, which was headed by the JLP, and toward the PNP, which in 1969 elected Michael Manley as leader.

Between 1969 and 1972, Michael Manley accumulated support. At that time, there was a hybrid emergence in Jamaica of two movements: black power, with its North American resonance, and Rastafari, which was an indigenous Jamaican black nationalist movement that followed its own trajectory. Michael Manley was able to harness this energy and win the insurgent youth, or a significant section of them, to the PNP.

Interestingly, Michael Manley started off as a moderate in the PNP, some would argue to the right of his father. But in the process of becoming the leader of the party, he began to move left. He was responding to tremendous pressure from below, from a contingent of young people observing that Jamaica has now been independent for a decade but black people still don’t have jobs or money, and the wealth is still concentrated in the hands of either foreign investors or local white and light-skinned elites.

In 1972, the PNP captured that sentiment with the slogan “Better Must Come,” which is the name of a song by reggae artist Delroy Wilson. The party also used that song in their campaign. So, when Manley won the 1972 election in something like a landslide for Jamaican politics, there was a heavy expectation that he would carry out measures that would “make better come.”

You mentioned reggae, a topic that brings us closer to understanding the meaning of the photograph. What was the relationship between reggae and the political movement of which Manley was at the helm?

They are closely intertwined. Reggae is very important in this political moment

Reggae as a music form was part of a rapid evolution that took place in Jamaican music in the 1960s. It started with ska, which had a 2/4 rhythm like reggae but was performed at a much faster rate, linked into a jazz tradition and influenced by rumba from Cuba next door and also music from New Orleans, which was the only music we could access easily from the United States on short-wave radio.

Ska evolved very quickly in the ’60s into rocksteady. And then, in the very year in which these urban riots around Walter Rodney took place, in 1968, reggae emerged as a new music form. The early acts were people like Delroy Wilson, who I just mentioned, as well as Prince Buster, and the Wailers, which is the band Bob Marley emerged as the leader of.

Reggae was a militant form of music that was closely linked to Rastafari and the black power movement. Of course, reggae spans the spectrum from romantic and emotional music called lovers rock, to hardcore protest music, to quasi-religious music associated with Rastafari.

Reggae was the soundtrack of the new political movement, and more particularly the soundtrack of Michael Manley’s 1972 electoral victory. Many of the key reggae personalities were very close to the campaign, and reggae artists had followed the campaign around the country playing at meetings.

However, there was also a tension when it came to Rastafari, which, as a whole, jealously guarded its independence from overt connection to politics. To fast-forward a bit, this helps explain the autonomy of Marley in 1978 in the picture we are discussing.

Rastafari was at once a political, religious, and aesthetic movement. As a religious movement, it had broad reach, which meant that there were also a few Rastafari who supported the JLP and Edward Seaga, who emerged as the JLP’s leader over the course of 1973 and ’74.

Who is Edward Seaga, and what social forces does he come to represent?

Seaga was a Jamaican of Lebanese descent who developed his influence in the JLP because of his dominance in one of the poorest parts of Kingston. There, he built an enclave called Tivoli Gardens, which was well-run and efficient, with social services, new high-rise housing, and cultural facilities.

Seaga used this base to build up a solid block of support within the JLP, and he assumed leadership just at the moment when the PNP was moving from its generalist slogan “Better Must Come” to the new slogan of democratic socialism in 1974.

The PNP saw itself as a socialist party in the beginning, but it had for several decades subsumed socialism under the mantle of fighting for independence. And even for a decade after independence, there was no talk of socialism in the PNP. But in 1974, in an attempt to consolidate its support and develop a program to move the country forward, the PNP under Manley rededicated itself to democratic socialism.

In response, the JLP under Seaga moved to become an anti-socialist party. The JLP evolved from a loose opposition into a coalition of both workers and capitalists who were standing clearly against the direction the PNP wanted to take the country, which was explicitly democratic socialist. It implemented reforms like a tremendous urban housing program, a literacy program, and maternity leave.

So we had in 1974 a bifurcation between PNP under Manley, which was adopting a still-moderate notion of democratic socialism, and the anti-socialist JLP under Seaga. This is a critical time, because it’s also when other developments are taking place globally, and the United States starts to come into the picture.

How was Michael Manley’s democratic socialist government received by the United States?

Jamaica came to the attention of Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger when, in 1972, four Caribbean governments recognized Cuba, breaking it out of the isolation it had been in for the previous decade. Those four countries were Guyana, Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, and Barbados.

That event foreshadowed what would occur in 1974, when Angola became independent from Portugal, which was followed almost immediately by the incursion into Southern Angola from Namibia, which was under the effective control of South Africa.

Cuba promised to support Angola, whose independence was threatened, but it couldn’t do it alone. That support could only reach Angola if the planes that carried heavy equipment could refuel. Both Barbados and Guyana, supported by Jamaica, agreed to offer refueling stations on the Atlantic. And this brought Jamaica into the crosshairs of Kissinger.

Kissinger visited Manley and requested that he not assist the Cubans, and Manley refused, explaining that helping Cuba defend independent Angola against apartheid South Africa was a matter of principle. He would not back down.

The record would suggest that this was the moment when the United States began considering efforts to take down Manley’s government.

Between 1974 and 1976, violence began to increase in the inner city, particularly in Kingston but also in other parts of Jamaica as well. This violence was mostly taking place in and directed at poor communities, perpetrated by a whole inbuilt system of gangs that were supportive of the political parties.

What was the root cause of this sudden paroxysm of political violence?

It’s still not entirely clear who was doing what, but what is clear is that violence started happening and then escalating not long after the PNP explicitly declared a democratic socialist agenda.

Nobody has a smoking gun, but it stands to reason that a government in power has no interest in creating a destabilized situation that will lead people to question whether it is capable of governing. The sequence of events suggests that the violence was not initiated by forces supporting the government, but rather forces opposing it.

There has been plenty of speculation that the CIA is responsible for initiating or at least inflaming the political violence.

It wouldn’t have been difficult to accomplish. There was already fierce division between rival party-affiliated gangs. Even just some extra firearms and some cash incentives would have made a difference. That kind of thing would have been consistent with confirmed CIA activities around the world in the 1970s and ’80s.

Absolutely, and like you say, there was already an infrastructure of gangs that were linked to political parties, but semi-autonomous and operating in their own interests, seeking their own profit margins.

Having said that, it takes two hands to clap. There was undoubtedly a response from the gangs that supported the PNP, resulting in tragic incidents perpetrated by both sides. By 1976, which was an election year, this violence had escalated to a paramilitary level on the streets of Kingston.

The 1976 elections were thus held under a state of emergency, because Manley felt it was the only way to control the violence. The JLP cried foul. They maintained that they were not the perpetrators of the violence and said that the state of emergency was declared so that they would lose the election.

At any rate, Michael Manley won reelection and consolidated and increased support in comparison to his initial election. The violence eased up after 1976, but then began again in the years leading up to the next election in 1980.

This violence was on a scale that’s hard to imagine. In one year alone, over eight hundred people were killed.

In many cases, the violence was indiscriminate. You had paramilitaries driving through communities, seeing a member of an opposing gang at a bar or on a street corner, and opening fire.

Both sides were engaged in a program akin to ethnic cleansing, but in this case, the objective was partisan cleansing. The neighborhoods in Kingston have clear partisan affiliations, and the gangs began programs of displacement in an attempt to drive people from the neighborhoods.

In some cases, whole city blocks were burned. The idea was that if these people flee and become refugees, forced to move and squat on land sometimes many miles away, they take their votes with them. You could swing a constituency from one party to another that way.

It was vicious. And again, when we consider the sequence of events, the direction of the arrow points toward enemies of Manley’s government, because it’s irrational for a government in power to create this level of disturbance, which reflects badly on its ability to govern.

That seems especially true given that Manley’s government was dealing with another problem after the 1976 election: an economic crisis, followed by coercion from the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Yes. The PNP under Manley had come to power in 1972. In 1973 was the OPEC crisis. Jamaica being essentially an energy-dependent country, prices increased dramatically. Meanwhile, because of the depression initiated by the crisis, key products for export were falling. And on top of that, tourism was declining because of the political violence.

By the time Manley won reelection, there were significant fiscal problems on the horizon. His government attempted to figure out a solution that would not involve going to the International Monetary Fund, but ultimately, he could see no other way. The first IMF agreement was signed in 1977.

The first agreement that Manley negotiated required structural adjustments and fiscal cutbacks in exchange for loans, but these were relatively mild. However, if the rules in the fine print were breached, then the IMF could impose another agreement. In the fall of 1977, the Jamaican government breached that fine print, and the new requirement imposed increasingly draconian measures.

The requirements of the IMF made it hard to keep implementing the democratic socialist programs that had bought the PNP so much goodwill leading up to the 1976 election. Eventually, the support that those programs won for the PNP was squandered. So, by 1978, the Manley government faced an economic crisis, a political crisis, and rampant violence.

We’ve made it up to 1978, which is the year our photograph was taken. Let’s bring reggae and Rastafari back in. How were they intersecting with politics and violence in Jamaica during this fraught period?

Rastafari represents a sort of ameliorating force that extended across these inner-city communities and provided a sage-like voice of unity. There were people who could cross lines because they were Rastafari. They could travel from Lower Trench Town, which was JLP territory, to Upper Trench Town, which was PNP, without being interfered with.

Rastafari began calling for a sort of Garveyite unity of black people. There were two parties struggling for dominance, one representing democratic socialism and the other fighting against it. And then there was Rastafari as a sort of countermovement, which didn’t have a headquarters or a center, but provided a moral perspective on a higher foundation. This is not to say that there weren’t individuals who were in the PNP or the JLP, but that there was a sort of autonomy that Rasta expressed.

Rastafari had gravitated to the PNP in 1972, but they were never completely won to the movement. Now they weren’t turning their back on the PNP, but they were saying, “Political parties are not the heart and soul of our movement. The heart and soul of our movement is black people, and we can’t be killing each other.”

How did Bob Marley fit into all of this?

There’s a song called “Rat Race” on Marley’s 1976 album Rastaman Vibration which is about the political violence, and in it, he sings the line “Rasta don’t work for no CIA.” This was a classic statement around that time, expressing a cautious alliance between critical elements of Rastafari and the PNP, but also a weariness about the rivalry between parties.

In late 1976, Marley was shot in a famous invasion of his house. And this was critically important, because it was directly related to the political situation.

Leading up to the ’76 election, Marley was invited to present a concert by the minister of culture at the time, so it was seen as a PNP concert even though it was a government concert. Marley was shot shortly before the concert, and it’s now pretty much certain that he was shot by a JLP gunman who wanted to stop him from bringing his significant presence to bear on an event that would redound to the interests of the PNP just before an election.

He held the concert anyway, the Smile Jamaica Concert, which was a very famous concert. And of course, the PNP won the election. But after that, Marley left the country and stayed in exile in the Bahamas and then in the UK, only returning for the Peace Concert in 1978.

The Peace Concert is the event at which the photograph was taken. What was the purpose of this event?

In 1978, under the influence of Rastafari leader Mortimer Planno, two of the critical leaders of the party-affiliated gangs — Claudius “Claudie” Massop of the JLP, and Aston “Bucky” Marshall of the PNP — came together and decided they were going to initiate a peace movement.

This peace movement was contradictory. It was being led by gang members who had been involved in atrocities. So it was always fraught, and there was some question as to whether it was genuine or whether these gang leaders, in a sort of mafia-type tradition, were looking to get the upper hand and get something out of this.

Either way, it’s undeniable that, on the grassroots level, particularly in the areas that experienced the most violence in this period, there was a tremendous groundswell of support for a peace movement that would end the violence. People had experienced four years of killings and burnings, and they were really ready for it to come to an end. This is what led to the Peace Concert.

You were at the Peace Concert. What was it like?

It was a remarkable event. It was held in the largest venue of its kind, the National Stadium in Kingston. Nearly thirty-five thousand people were there. All of the leading reggae singers were there. And all of the gang members and gang leaders were there, and there was peace between them that evening.

It had this sort of atmosphere that you sense in moments of potential change, in which the impossible seems possible. It was almost like a revolutionary moment.

The two most outstanding personalities among the Jamaican pantheon of reggae singers were Bob Marley and Peter Tosh. The latter had also been one of the Wailers, the three original members being Bob Marley, Peter Tosh, and Bunny Wailer.

What was interesting is that Peter Tosh’s presentation, which lasted for an hour that night, essentially didn’t support the peace initiative. His attitude was captured in his famous 1977 song “Equal Rights,” in which he sang, “I don’t want no peace, I want equal rights and justice.” Tosh’s slogan ran against the grain of the event, which was more celebratory.

So Peter Tosh held one position, and Marley held another. Great artists performed all through the night, but Marley’s performance was the high point of event. He performed just around midnight. And, as you can see in the photograph, he called Manley and Seaga onstage, and he brought their hands together — quite different from Peter Tosh’s attitude that night.

But it’s complicated because, on the one hand, yes, Marley is calling for the violence to end. But if you listened to the music Marley played that night, it was music directed against Jamaica remaining within the bounds of its neocolonial past. It’s almost as if Marley is saying with this gesture that Manley and Seaga have got to find a way to end the hostility so that we can actually change the country, which was the spirit in which Manley was elected.

Of course, Marley sings about one love, but it’s not one love in the abstract. It’s one love coming together to make a change, and it’s not divorced from the idea of fundamental structural transformation in Jamaica. Marley’s position is that ending the violence will allow a politics of social and political change to proceed.

Afterward, there was an interesting debate in the newspapers, initiated by an article in the radical newspaper of a small Marxist-Leninist party called the Workers Party of Jamaica, a newspaper called Struggle. That article essentially said that Peter won the night. Bob didn’t like it one little bit, and he was up at the offices of the newspaper the next day, cursing, saying basically, “You’re making out Peter as a revolutionary, and I am what?”

So there was a side debate going on about whether Bob had sold out by doing this, whereas my reading of Bob at that moment is that he was thinking, “If only working people can have peace, then we can begin to change this country.”

Now that we’ve provided sufficient context, let’s take a look at our photograph again.

What happened after that night?

Within a couple of years, both gang leaders, Claudius Massop and Bucky Marshall, were dead. The peace agreement didn’t hold up. The violence increased dramatically going into the next election. And in 1980, against this background of violence and an IMF agreement that was strangling the country and harming working people, the PNP were defeated, and Seaga became prime minister.

The Manley attempt at democratic socialism failed. Ronald Reagan was elected almost simultaneously with Edward Seaga, who visited Reagan in 1981. Bob Marley also died of cancer in 1981. So that is the sort of denouement, if you wish, of this whole process.

Manley went into opposition, and in 1989, he was reelected, but he came back as a far more tamed leader who was operating within the confines of the Washington consensus.

It’s like Manley was a leader who responded to his moment. The moment was revolutionary in the early 1970s, but it was hardly revolutionary come the 1990s.

Precisely. By the time he returned, the moment had passed; the world had moved on. The international conjuncture that allowed for the existence of radical states had been eclipsed. Manley came back as a completely different person. On his deathbed, he said he regretted some of the decisions he felt he had to take in the ’90s, but that’s for the history books.

Given the way that Manley’s government ended, has history proven Bob Marley right that, without peace in the streets, all revolutionary hope for Jamaica would be extinguished?

History has proven him right to the extent that the failure of a peace treaty led to the rise in violence, and that the result of the 1980 election owed to the feeling that the country was ungovernable. Many people would say after the election that they liked Manley and his policies, but the country was at war, and the only way to stop the war was to let Seaga rule.

But the violence wasn’t the only thing that precipitated Manley’s defeat. There was also the untenable economic situation, made worse by the country’s IMF agreement. Real wages had shrunk significantly, you couldn’t find certain goods on the shelves of supermarkets — all of the classic features. Nixon said it in relation to Chile: “Make the economy scream.” The Jamaican economy was screaming in 1979 and 1980.

Maybe it was not possible for there to have been a viable peace agreement, because ultimately, it was happening on the level of warlords, not politicians like Manley and Seaga. But we will never know what would have happened if peace had been possible and had been achieved.