The Young Eugene V. Debs

A pair of leftist historians has undertaken a massive project: compiling a six-volume collection of Eugene Debs’s writings and speeches. We spoke with one of them, who detailed Debs’s extraordinary journey from moderate young trade union leader to courageous socialist militant.

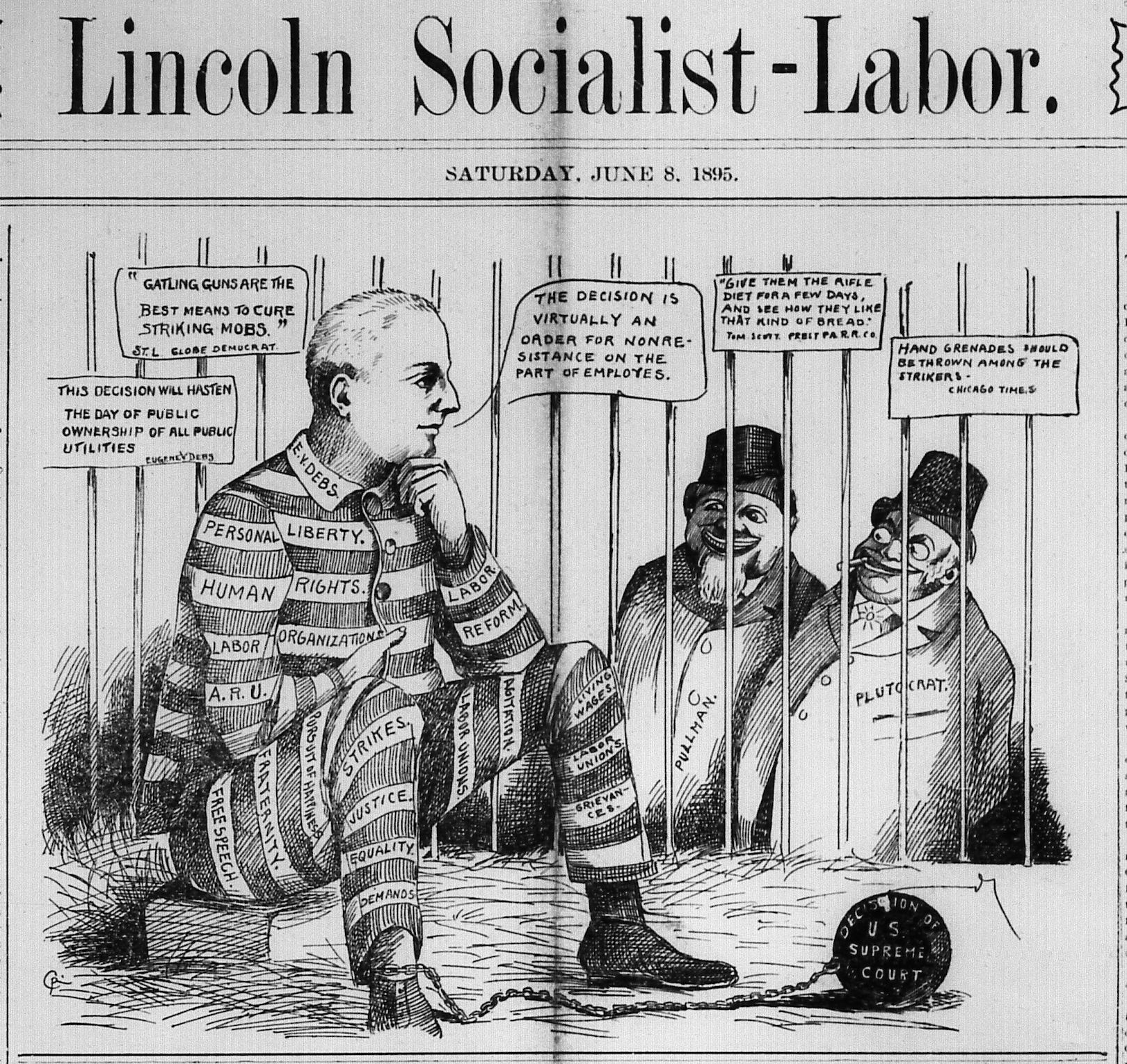

A drawing of Eugene Debs from the 1895 book A Momentous Question.

- Interview by

- Shawn Gude

“In the gleam of every bayonet and the flash of every rifle the class struggle was revealed,” Eugene V. Debs wrote in 1902, recalling the state violence used to put down the Pullman Strike he had led eight years earlier. “This was my first practical lesson in Socialism.”

Debs had come a long way. Known today for his blistering denunciations of militarism and Gilded Age plutocracy, Debs — born in 1855 — started out as a moderate trade union leader. The Pullman Strike, which broke out among workers with the Pullman Palace Car Company in 1894 and quickly rocketed across the railroad, was one in a series of events that pulled Debs to the left.

The first two volumes of The Selected Works of Eugene V. Debs, an ambitious new collection that will eventually comprise six installments, cover these earlier years of Debs’s life. Jacobin’s Shawn Gude spoke with Tim Davenport, one of the coeditors of The Selected Works, about how he got into the project, Debs’s transformation from moderate to militant, and the socialist leader’s relevance to today’s struggles for justice and democracy.

What’s your background, and how did you get into this project? As you note on the project’s website, it’s a massive undertaking — six volumes, millions of words to pore over.

Going through college in the early 1980s, I was planning on pursuing a PhD in Russian history. Unfortunately, I didn’t care for academia. After a few years making punk rock records to keep myself engaged, there came the great epiphany: I may have been an inferior Russian language student with insufficient skills, but I was a very intense history student. So why try to work in Russian?

I switched gears from the Soviet 1930s to the American 1920s, concentrating on the history of American radicalism. I began building a new personal library and started typing up documents for a planned magnum opus, an ecumenical three-volume history of American radicalism covering the absolutely critical period from the war hysteria of 1916 through the destruction of what was shaping up to be a mass communist party in 1924. Included in that period and looming large was, of course, the split of the Socialist Party of America in 1919–1920, including in its ranks Eugene V. Debs.

As I was getting ready to start work on this book, I put together a little website as a mechanism for storing and rapidly accessing typed documents as I would need them. I had managed to scrape together enough money to buy the first twenty-five or so reels of the Communist Party’s archive held in Moscow by the Communist International — this was just being published at the time via financial assistance from the Library of Congress. What a treasure trove! My unique content caught the attention of one of the volunteers at the Marxists Internet Archive (MIA), and he persuaded me to join forces with them.

Was this how you met your now-coeditor, David Walters?

Yeah. Once I was aboard with MIA I made the acquaintance of David Walters, one of the founders and the most active volunteers at the site. David saw this slew of previously unknown Debs documents that I was finding and typing up for my site — unknown outside of a couple scholars, I should say — and he was most enthusiastic: “Oh, this is great — you need to do a Debs Collected Works!”

I put him off for a long time, several years, but I did make a point of typing up every “new” Debs document that I came across, and he dutifully began building a first-rate “Eugene V. Debs Internet Archive” as part of MIA. This went on for several years: David gently pushing me toward doing a true Collected Works and me resisting because I knew how big the job would be. I told him at one point that it would take a team of five dedicated scholars a decade to do the job and that it would run to twenty or more thick volumes.

The key event came when I discovered the existence of The Papers of Eugene V. Debs, 1834–1945 microfilm edition. Back in the early 1980s, Debs historian Bob Constantine had worked with NYU’s Tamiment Library archivist Gail Malmgreen and made a solid attempt to list and film all the known publications and correspondence of Gene Debs. In 1990 Constantine had taken this project to the next step, publishing three volumes of selections from the correspondence as Letters of Eugene V. Debs. However, for whatever reason he had never adapted Debs’s published writing for similar treatment.

This was the real aha! moment — the “team of scholars” had already done most of the hard work of discovery, so the job was already half done! It was now possible for one or two people to resume that dropped project and carry it forward. Instead of ten years, the job actually could be done in five, I now guessed.

Why do you think Debs continues to be such a compelling figure? As you write in the introduction to the first volume, he’s been claimed by everyone from liberals to communists, and nearly a hundred years after his death, many young leftists still identify with his legacy.

Gene Debs is probably the most iconic figure in the history of American radicalism. He was the great evangelist for the Socialist Party of America during its period of greatest popular support. He ran for president five times, twice racking up over nine hundred thousand votes in third-party electoral efforts.

He, thus, is symbolic of a promising electoral past, of an attempt to remake the country through the ballot box that never quite achieved its goal or implemented its program, but which remains a promise of sorts for the future.

Debs is also a figure of incorruptible honesty and total life commitment to the cause. When many intellectuals folded their red silk flags, and began waving the stars and stripes and praising the so-called “war to end all wars” after American entry into the European bloodbath, Debs unflinchingly held true to principle and went to jail rather than renounce, retract, or soften his views. He was, figuratively and very nearly literally, a martyr for the cause of socialism, internationalism, and anti-militarism.

This is very attractive, very potent stuff.

This country has its political heroes, but they tend to come from other wings of the liberation movement: Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King Jr, Malcolm X, Daniel Ellsberg, Cesar Chavez, Harvey Milk, and so on. Debs is a political icon springing from the international socialist movement.

The Debs we find in the first volume is a much different Debs than the one people are used to — namely, he’s much more conservative. What was Debs up to in those years, and what were his politics?

The historian of American socialism David Shannon published a journal article in 1951 with the provocative title “Eugene V. Debs: Conservative Labor Editor.” I don’t think any serious Debs biographer has missed the fact since. That’s where he began.

The great legend of Debs was that he was a locomotive fireman who became a trade union official, fought a mighty strike in 1894 for which he bravely went to jail. In jail he was won over to socialism through a timely gift of a copy of Das Kapital, and he emerged a committed international socialist who founded the Socialist Party and led it to near victory before being cruelly repressed during World War I. This is a fast and easy oversimplification, of course, but there’s probably a lot of head nodding taking place as I recite that brief trajectory.

Actually, Debs was a well-loved middle-class kid that dropped out of school in his early teens to pursue a career as a railroader, attending business school in his spare time. Then he worked as a warehouseman and bookkeeper for a large grocery wholesaler.

He was elected the city clerk of Terre Haute, Indiana at the age of twenty-four, served two terms in that capacity, and was elected to the Indiana state legislature as a Democrat before he was thirty. A skilled public speaker who actively studied the orator’s art, he was a golden boy of the Democratic Party of Indiana. His future was bright.

He became a top functionary of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen in the early 1880s. This was not a modern union that engaged in collective bargaining, but was rather a fraternal benefit society that provided low-cost insurance to its members, and which published a magazine which attempted to edify the rough-hewn firemen. Debs was the chief money manager and the magazine editor for this organization for more than a decade, and he was very well compensated for his services.

Debs began life as a pro-labor Democrat with a very modest, thoroughly parochial worldview. He introduced pro-labor legislation in the Indiana legislature and saw it gutted. He lost his faith in the Democratic Party, hitching his wagon to the emerging People’s Party as a more forthright vessel for his views.

He also, as an active and talented labor magazine editor, watched the emerging strike movement with open eyes and gained class consciousness watching the battles of underpaid and physically abused railway workers against the powerful companies they worked for.

That’s the really interesting storyline of Debs Volume 1 — what he was and what he gradually became.

The vast majority of the material in the first two volumes hasn’t been published since their original appearance. Were there any particular selections that stood out to you as encapsulating the young Debs?

His first truly great, epochal, landmark, everybody-should-read-it speech came when he was released from Woodstock jail, delivered at the National Guard armory in Chicago in 1895, and published and republished and republished again under the title “Liberty.” But I will really need to think hard to figure out a single piece that epitomizes his early ideas about individualistic self-improvement.

For now I guess a tiny little Locomotive Firemen’s Magazine piece from June 1882 called “Sand” gets us there. Here is part of it:

Sand means grit; it means the power to hold on. When an engine is called upon to exert its greatest strength it needs sand to give it a better grip on the track. When men are called upon to exert their greatest mental strength, sand is necessary. Men who have plenty of sand in their boxes never slip on the path of duty. Wet weather and greasy tracks do not affect them, their sand will not let them fail…. Be it at the bedside of the suffering or in the wild rush of the midnight train, the man of sand does what he is called upon to do, quickly, calmly, boldly — no quiver in his iron nerve. Death alone can conquer the man of sand.

That’s early Debs in 125 words.

Now, the thing that really interests me from the first volume of the Selected Works, speaking as a historian and a socialist, isn’t the output of the early Debs so much as his first, failed effort to federate the various railway brotherhoods into a de facto single entity under the aegis of the Supreme Council of the United Orders of Railway Employees. The railway brotherhoods gradually transformed from fraternal benefit societies to true trade unions during the course of the 1880s.

The failure of the 1888 Burlington Railroad strike due to strikebreakers and the inability of the craft brotherhoods of the so-called “running trades” — engineers, firemen, conductors, and brakemen, together with their rowdy cousins, the switchmen — to remain united and win this long and bitter work stoppage fundamentally changed Debs’s thinking.

He moved from becoming a simple labor editor and started becoming a true labor organizer, attempting to build a structure that would bring these stodgy and independently minded brotherhoods together under a single commanding staff, composed of a committee of their own elected leaders, that could issue simultaneous strike instructions and hold together these different trades in a single phalanx that could actually win such a strike.

The best paid crafts — the conservative, anti-strike engineers and conductors — refused to join. Then the brakemen and the switchmen got into a nasty jurisdictional battle, and the whole Supreme Council idea suffered an ignominious collapse.

And then out of this grew the American Railway Union (ARU), which dominates the second volume. Can you talk about the ARU, the Great Northern strike, and then the most monumental of walkouts, the 1894 Pullman Strike?

The ARU was a pioneering attempt at true industrial unionism — bringing together workers of all crafts within a single industrial group. Debs, in this period, was not thinking in terms of politics, he was committed to labor organization to go to battle with capital on the industrial field.

The successful Great Northern strike of April 1894, settled in favor of the ARU by arbitration, reinforced in Debs the belief that he was on the right track with the ARU idea. United action brought the Great Northern Railroad to the bargaining table, and Debs cleverly agreed to accept binding arbitration by a body which included leading shippers of the region.

Unable to have federal troops dispatched to settle the strike by force, Great Northern president James J. Hill agreed to the arbitration scheme. Much to his chagrin, the arbitrators ruled against his wage rollback, and Debs was hailed as a hero.

To some extent this early victory set up the devastating, union-crushing loss of the Pullman Strike of the summer of 1894. Delegates to the regularly scheduled “First Quadrennial Convention” in June were overconfident; the railroads, on the other hand, were united by a loathing of the new industrial union. They feared the consequences down the road if early success was allowed.

The ARU ended up walking into a buzzsaw and was annihilated by the alliance of railroad managers, the federal government and its military, and a pliable federal bench.

Debs ended up in prison for his role in the Pullman Strike, which became one of the central stories in the myths surrounding his conversion to socialism and subsequent exploits. Could you talk about Debs’s tendency to encourage this mythmaking? What do we actually know about his move toward socialism?

Debs was a massive figure in the history of American socialism and worthy of great honor, so don’t get me wrong here, but Debs definitely scattered misinformation over the course of his life. He pretended to have won a Bible as a prize for excellent spelling as a schoolboy but never to have read it. “Read and Obey!” his teacher wrote in it. “I never did either!” Debs added, telling the story to friends.

In reality, Debs absolutely cannot be understood outside the context of the Protestant social gospel movement of this era. He was well versed in the Bible, and believed that the life and words of the historical Jesus had important lessons to teach to the modern man. He was, to my way of thinking, the most radical of Christian socialists.

This doesn’t make Debs a good guy or a bad guy, but it was deeply a part of who he was.

Similarly, Debs was not always a reliable narrator of his social origins, his early aspirations, the reasons he left one profession for another, the story of his conversion to socialism, and so forth. He was not a liar or a megalomaniac or a falsifier, but he had his own particular slightly skewed truth. The two main biographers — Ray Ginger and Nick Salvatore — have caught on to this. Read them closely and think if you really want to understand the essence of the man.

Again, this doesn’t lessen Debs’s achievements in the slightest. But don’t confuse hagiography with biography. There is plenty of the former as well as the latter.

In terms of Debs’s commitment to socialism, we know that he and his ARU comrades had books by Laurence Gronlund and Karl Kautsky, and constituted themselves the “Cooperative Colony of Liberty Jail,” so you will forgive me for rolling my eyes when Debs thanks the most powerful figure in the Socialist Party of that time, Victor Berger, in a high-profile article published six years after his release thanking him for his conversion via a signed copy of Marx’s Capital.

Did Debs himself believe the story he told? Probably. Does the evidence support it? No.

Looking ahead, I was wondering if you had any thoughts about the upcoming volumes? I know the third is due out this winter.

Here’s what’s coming down the pike:

Volume 3 is subtitled The Path to a Socialist Party, 1897–1904. That pretty much sums up the main story arch, beginning with Debs’s public declaration that he was a socialist on January 1, 1897 through to the end of his second run for president in 1904.

This is a book for the political junkies and the historians of socialist organizational structure. I eat this stuff up, personally. It’s a story of half-baked utopian schemes and fledgling political parties and interpersonal, interorganizational machinations leading to the rarest of all birds: socialist unification, rather than split.

What readers will learn is that Debs was not the father of the Socialist Party of America. He quickly came to embrace the new party and dedicated the rest of his life to it, mind you, but he was not the intellectual father or the founder, or really much more than a disgruntled, defeated factionalist at the moment of its creation.

It’s a pretty interesting story, one that has been more or less missed by the biographers, but one that becomes very clear with the documents. This volume still needs to be indexed, but should be out on schedule in December.

Volume 4 is subtitled Red Union, Red Paper, Red Train, 1905–1910 and deals largely with those three things: the red union being the founding of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), the red paper being the Appeal to Reason and Debs’s high profile as a contributor to that mass circulation publication, and the red train being his legendary 1908 presidential campaign side by side with his brother, friend, and co-thinker Theo Debs. I’m guessing this will be out in the middle of 2021.

Volume 5, my current focus, is subtitled Breakthroughs and Breakdowns, 1911–1916. This one will deal with Debs’s reaction to the Socialist Party as a successful mass political party, with hundreds of elected officials nationwide. Then comes the fascinating campaign of 1912 — which was really the Socialist Party’s best chance to win, the Republican Party having split between incumbent president William Taft and former president Theodore Roosevelt. This volume will deal not only with the breakdown of socialist unity but with Debs’s own health breakdowns — his first two of three “nervous breakdowns.” This one will probably roll out at the end of 2021.

Volume 6 is subtitled The Perils of Pacifism, 1917–1926 and will deal largely with Debs’s anti-militarist writing, his imprisonment, his fifth and final presidential campaign from behind prison bars, and his work as an advocate for political prisoners and prison reform in the aftermath.

It will also deal extensively with his reaction to the Bolshevik Revolution and the foundation of the American communist movement. This book will include a decade’s worth of output whereas all the other volumes are about half a decade, but Debs was in jail for two and a half of these years, and his output dwindled as his health declined, so I think we’ll be able to pull it off. This will be a 2022 publication.

I hope that the Selected Works of Eugene V. Debs project helps in some small way to restore Gene Debs to the ranks of American socialist writers and commentators. I have a feeling it might. Debs as a writer and orator has been given short shrift, I believe — he had something to say and a style of saying it, and ideas about democracy and liberty and solidarity and empowerment that should resonate today. Liberty and freedom are authentic left-wing concepts — we need to embrace them and stop surrendering these ideas to the Right. They are the oppressors, not us.

Debs’s life has been held up as an exemplar of commitment and honor and virtue and incorruptibility. When we look at these things with the historian’s magnifying glass, that may be an oversimplification of a complex and flawed human being, but that’s okay — graded on a curve, Debs still earns his A+ as a committed fighter and willing martyr for a great cause. The new generation taking a good look at our collective past, at the life and ideas of Gene Debs and people of his milieu like Morris Hillquit and even Victor Berger, is all for the good.

There is a valid American socialist tradition which needs to be discovered and embraced. Our past powers the future.