Tech Billionaires Think SimCity Is Real Life

Tech companies are getting into the business of making cities. We need to stop Silicon Valley social engineering before things get even worse.

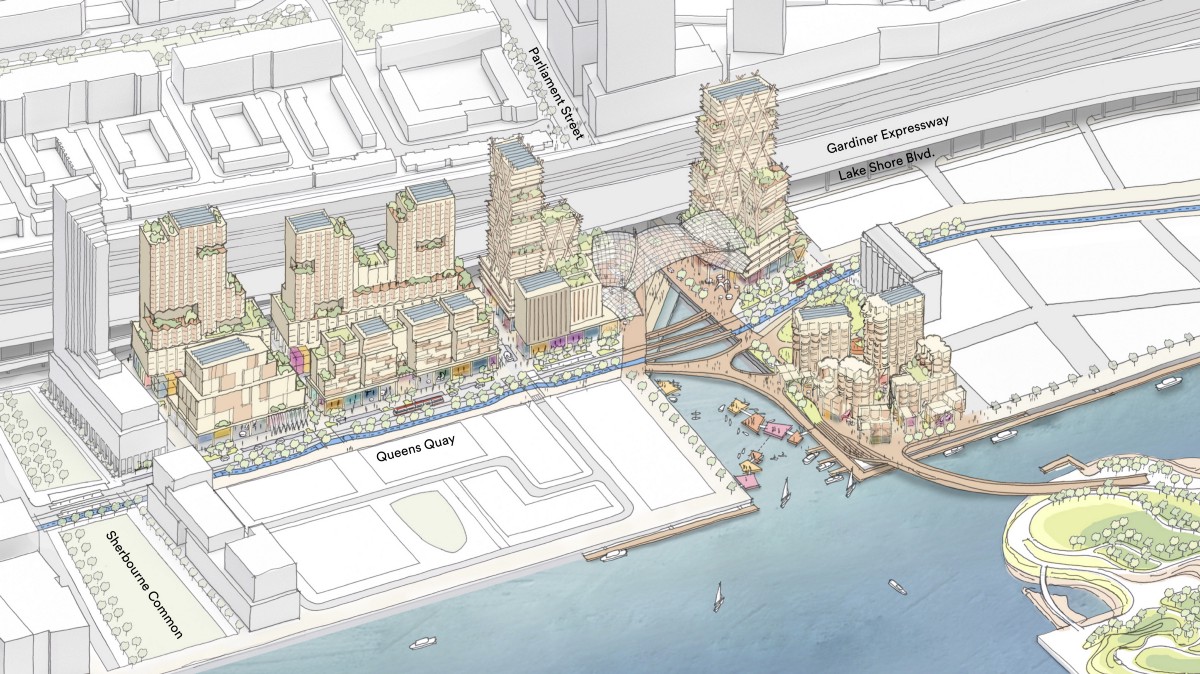

Proposed Quayside site plan. Sidwalk Toronto / Medium

For a long time, the titans of tech — Facebook, Google, Amazon — were difficult to locate. Sure, we knew they each had an address. We’d seen the One Hacker Way sign on Instagram. We were fairly certain actual people worked there. But until a few years ago tech companies felt a bit ephemeral. They existed, to a large extent, in our imaginations. The world they commanded seemed immaterial, a place of clouds, bytes, and weightless “experiences.”

The stories we tell about digital technology are partly to blame for this fuzziness. Look no further than the cyberspace montage — a cinematic staple of alternating streams of neon code overlaid onto fast cuts of poorly lit hackers pawing at their keyboards — for evidence of our inability to imagine the spaces and places created and occupied by tech companies.

But tech companies have also been happy to leave us to our fantastical notions. Despite their friendly branding, Google, Facebook, Apple, and others like them are intensely secretive. Tech campuses are often closed, their public-facing architecture monolithic. Supply chains are proprietary, horizontal, and highly globalized. Many of the people necessary for modern tech’s core functionality are hidden or not counted as official employees, while nondisclosure agreements are de rigueur. Data centers are located in out-of-the-way places, often housed in old military bunkers or nondescript warehouses and, as the Washington Post recently reported, many are owned by shell corporations.

Increasingly, however, the tech titans are coming into focus.

These days it’s easier for us to conjure a concrete constellation of facts, places, and events related to big tech — to associate a sense of structure and power with the apps on our home screens.

This emergent clarity is a result of the rapid expansion and visibility of these companies. For example, Facebook’s billions of active monthly users, combined with revelations of a string of misdeeds the social media giant has committed over the past five years, have made CEO Mark Zuckerberg a regular topic of the chattering classes. People can sketch a recognizable portrait of America’s favorite robber baron.

We’ve also become better acquainted with tech workers. Recent walkouts and protests by Google workers over the company’s sexual abuse cover-up and eagerness to help the US military grow its drone warfare operations showed us what tech workers looked like “in real life.” We saw that they didn’t just live in Silicon Valley, that they could make signs, and that they cared about the same things everyone else did.

The increasing clarity is also aided by tech companies’ growing brick-and-mortar presence. Amazon adds over a million new products to its online store every day. Its fulfillment centers and warehouses now dot the United States and countries around the world. Recent additions include Amazon lockers, staffed pickup and return points, and retail locations, including more than 450 Whole Foods stores.

Tech companies’ expanded footprint comes with an expanded vision. It’s a tight race but Google leads the pack in ambition. In 2015 the search engine company’s founders, Larry Page and Sergey Brin, folded its operations into a mammoth conglomerate called Alphabet that today houses venture capital and private equity firms, a tech incubator, and a string of companies focused on biotech and the life sciences, artificial intelligence, broadband internet, wind power, autonomous vehicles, and drone technology.

Nothing demonstrates Alphabet’s ambitious vision better than its recent move into the business of making cities. In 2017 Sidewalk Labs, formerly part of Google and now an Alphabet subsidiary, won the rights to submit a proposal (the Master Innovation Development Plan, MIDP) to develop a section of the Toronto waterfront. Under the direction of Daniel Doctoroff, a property developer and former deputy mayor of New York, Sidewalk Labs is hoping to build a new village called Quayside, pending approval of its MIDP.

Quayside fulfills a long-standing dream of Alphabet. At the project’s launch, chairman Eric Schmidt described how Googlers had long fantasized about “all the things [they] could do if someone would just give [them] a city and put [them] in charge.” They finally got their wish.

Waterfront Toronto (a development corporation funded by the Canadian government, the Province of Ontario, and the City of Toronto) put out a call for proposals to develop a section of the Toronto waterfront and ultimately chose Sidewalk Labs’s proposal. Alphabet’s urban development company promises to build a “new type of place that combines the best in urban design with the latest in digital technology to address some of the biggest challenges facing cities, including energy use, housing affordability, and transportation.”

Quayside — “the world’s first neighborhood built from the Internet up” — bills itself as the city of the future. Ubiquitous sensors and cameras will gauge resident flow, traffic, and weather. Self-driving vehicles will radically reduce the need for personal car ownership. Residents will relax in tall-timber plug and play buildings serviced by underground trash and delivery robots. More broadly, Quayside is seen as a laboratory to develop a new city platform model — a city-scale Android phone — that Alphabet can someday license and sell to other cities around the world.

Alphabet executives follow a long line of corporate dreamers: George Pullman, Milton Hershey, Henry Ford, Walter Kohler. Of course, these men and their eponymous industrial communities are familiar in no small part because their experiments failed. company towns were designed to solve the ills of industrial capitalism — blight, shoddy housing, and most of all a disgruntled, politicized, militant workforce. Instead, they quickly demonstrated the dystopian reality of unchecked corporate power.

The debacles of Pullman and Fordlândia have pushed the planners of modern corporate city projects to publicly disassociate themselves from the company town concept. Nonetheless, historical failure hasn’t served as a serious deterrent. Once again the captains of industry are hoping the city can unlock the promise of capitalism.

Apart from Alphabet, Facebook is building a new city in Silicon Valley called Willow Village between Menlo Park and East Palo Alto (though it bristles when reporters call it “Zucktown”). Bill Gates recently bought twenty-five thousand acres in Arizona to construct Belmont, the City of the Future, while cryptocurrency millionaire Jeffrey Berns purchased sixty-seven thousand acres outside of Reno to erect a blockchain utopia.

“Smart cities” have been around for some time. The “smartest city in the world” is Songdo, majority owned by Gale International, a private real estate developer based in New York City. Songdo, built in Incheon, South Korea on land reclaimed from the Yellow Sea, boasts a pneumatic trash system, a state-of-the-art water recycling facility, traffic and energy use sensors, remote touch screen regulation, and vast green spaces.

Songdo, despite its description as a “sustainable, low-carbon, high-tech utopia,” is curiously empty, however. Its pristine, wide avenues and replica of New York City’s Central Park are often deserted, sparking Chernobyl comparisons. Residents report feelings of isolation and loneliness and complain that the city is unaffordable.

Other would-be smart city founders have watched the fate of Songdo carefully. Indeed, its shortcomings may explain why Sidewalk Labs has been careful to involve the Toronto community in the planning process. In an effort to build trust and gather input, it has held town hall meetings and online Q&A sessions, hosts open office hours on Sundays, and runs a variety of community programs.

Torontonians have responded enthusiastically to calls for their participation. The problem however, at least for the Google spinoff, is that their input increasingly seems to be: “Get out.”

Over the past year and a half a group of Toronto residents, now united as #BlockSidewalk, has formed to block the Quayside project, citing deep concerns over privacy and surveillance, Alphabet’s demonstrated willingness to abandon unprofitable “moonshots,” and a more general anger at the undemocratic nature of the waterfront giveaway. “#Block Sidewalk,” the group explains, “is about taking back control of our city and its future. It’s about all of us. It’s about democracy.”

#BlockSidewalk is the latest in a string of rejections for tech companies looking to put down roots in new places. New York City residents revolted against Amazon’s plan to build its second headquarters in Queens. The “Everything Store” hoped to cash in on tax incentives, but many New Yorkers weren’t in the mood to give billions to the world’s richest man in exchange for a nebulous promise of “jobs” when the city’s public transit infrastructure is in shambles, its public education system is massively underfunded, and one in eight public school children are homeless.

Germans recently voiced a similar “Thanks but no thanks” when Google expressed interest in opening a thirty-two thousand square foot campus in the Kreuzberg neighborhood of Berlin. Activists, fearful that the project would further displace low-income residents in the rapidly gentrifying neighborhood, organized a two-year counter campaign entitled Fuck Off Google: “We, as a decentralized network of people want to keep our lives and spaces free from this law-and-tax-evading company that is building a dystopian future.”

These rejections signal not only broad disgust over the corporate giveaway norms of neoliberal capitalism but also growing distrust and fear of the power that tech companies have to remake both digital and analog spaces and places. They point to the growing centrality of tech in fresh struggles over the “right to the city.”

In City of Quartz Mike Davis argued that “greater equity in urban space including the basic right to remain in the city of one’s birth or choice requires radical interference with rights of private property.”

Today we’re seeing more and more instances of this radical interference — for example, in the grassroots initiative to expropriate Deutsche Wohnen, Berlin’s largest residential landlord. But in struggles like Toronto’s #BlockSidewalk, we also see a reconfiguration of the battle over the commons. As tech companies quantify and commodify new spheres of life, transforming them into private property, the city has emerged as a key site in the digital frontier.

Humanity is increasingly urbanized. And cities open up new opportunities for data generation and collection. As we go about our lives in urban spaces, in our homes, at work, on the streets, in the shops and subways, most of us are umbilically attached to our smartphones. We generate data with every step, search, and swipe. With ubiquitous sensors and smart devices, all synced to our own smartphones, companies like Sidewalk Labs stand to generate unprecedented data and to create new ways of extracting data from life.

As former Ontario privacy commissioner Anne Cavoukian says, “Technology is on 24/7. You can’t remove yourself from it. Personalised data is a treasure trove … that’s what everyone wants.” Cavoukian joined Sidewalk Labs as a privacy consultant but quit last October over the company’s plans to hand over control of the data generated in Quayside to an independent “civic data trust,” a move that Cavoukian says essentially gives anyone access to the data.

The battle over Quayside is one episode in a much larger reorganization of power in the twenty-first century. Alphabet/Google, Facebook, Amazon — these companies are the purveyors of much of the infrastructure undergirding modern social, political, and economic life. We depend on them. Our dependence has put them in a position of unprecedented power — the power to enclose and appropriate new spaces, both digital and analog. They are actively doing so.

The tech titans present themselves and their technology as inevitable. They expect and demand ever-greater access to our cities, our communities, and our selves.

Yet while many of us are increasingly uncomfortable with the norms of Silicon Valley companies, we also recognize the need to rethink our car-dependent, unaffordable, inefficient cities. We wonder how we’ll get greener, more sustainable cities when governments can’t even maintain the crumbling infrastructure we already have, let alone build new infrastructure or envision radically new ways of organizing urban spaces. Despite a looming ecological catastrophe, officials show little interest in reducing urban car use or building affordable, green, mixed-use spaces.

In this climate it’s easy to believe that companies like Sidewalk Labs are the least bad option. Indeed, despite spiking criticism, polls show that most Torontonians are still in favor of the Quayside project. There is a deep collective desire for the city of the future. Companies like Alphabet effectively capture that desire and our shared sense of urgency about the future. Sidewalk Labs’s vow “to accelerate urban innovation and serve as a beacon for cities around the world” resonates.

As David Harvey says, the idea of the right to the city “is an empty signifier. Everything depends on who gets to fill it with meaning.” These days tech companies and property developers are providing most of the meaning. In Sidewalk Labs’s technocratic vision “ubiquitous connectivity,” “cutting-edge technology,” “data-driven management,” and a “suite of design and infrastructure innovations” such as self-driving cars are the key to improving urban life.

Seeking to assuage fears that ubiquitous surveillance is the flip side of “ubiquitous connectivity,” Sidewalk Labs Head of Urban Systems Rohit Aggarwala reassures us: “Our objective is to build a great neighborhood. The only reason we want to capture information is to provide better urban services.” Unlike top-down visions of the past Sidewalk Labs promises transparency and openness. In a Reddit Ask Me Anything, one participant asked Doctoroff about the first thing he would build in Quayside. He answered, “a statue of Jane Jacobs?”

In this corporate story, consensus goals of “sustainability, affordability, mobility, and economic opportunity” become interwoven with and inseparable from Sidewalk Labs’s business plan. The sweeping privatization of new spheres of life made possible by the corporate-led reorganization of urban space is presented as the creation of an inclusive, green community built in the interests of everyone.

But Sidewalk Labs isn’t creating a commons. Far from it. Its goal is to make a profit for its parent company. At the end of the day, the primary aim of Sidewalk Labs, and all the other Silicon Valley giants, is designing and selling technology — enclosing and profiting from the emergent digital frontier.

Silicon Valley ideals — ubiquitous surveillance, the datafication and commodification of everything — are not the values on which to build the city of the future. Like all corporate visions for remaking urban space (opportunity zones, redevelopment schemes, charter cities) the future cities dreamed up by the tech titans will benefit elites, not workers.

The things that make cities livable today — public water utilities, public schools, parks, pollution restrictions — were championed by progressives, radicals, and grassroots movements. The struggle over the right to the city of the future will only be won if we fill it with our own meaning — if we take what’s ours.