Our Obsession With Personal Responsibility Is Making Us Sick

Poor health outcomes are often treated as an unfortunate by-product of individual bad decisions. This moralizing approach ignores the role poverty plays in determining who gets ill and who can afford to get well.

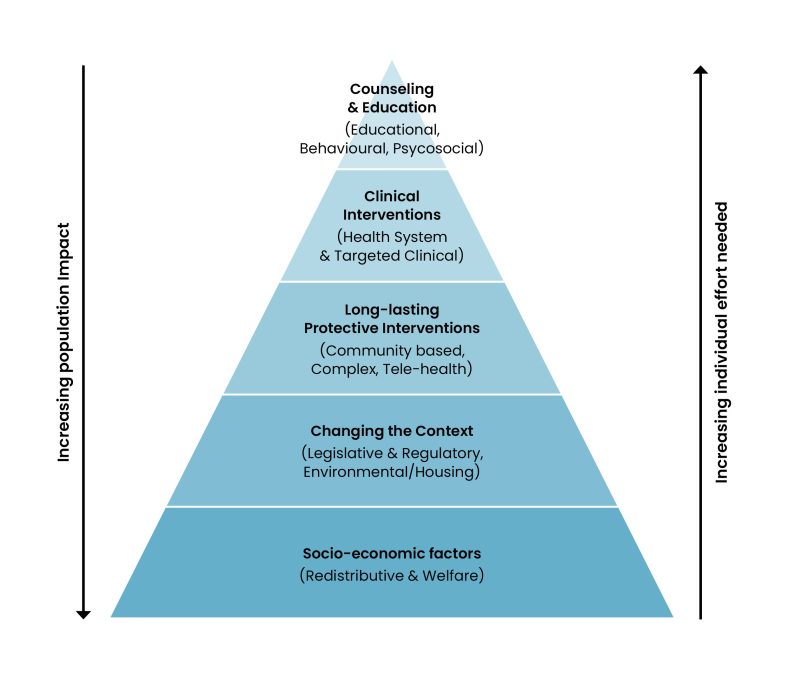

A sweeping review of public health evidence finds that interventions requiring the least individual effort — such as expanding housing and welfare — do the most good. This challenges the persistent tendency to blame poor health on personal choice. (Aaron Chown / PA Images via Getty Images)

Across high-income countries, inequality is routinely misdiagnosed. When life expectancy gaps widen, when preventable illness clusters among poorer communities, and when disadvantage hardens into predictable patterns of premature death, the explanation offered by governments is rarely political failure. Instead, responsibility is displaced onto individuals. Health outcomes are framed as the cumulative result of choices made well or badly, rather than conditions imposed or protections withdrawn. The state recedes, then moralizes about the space it vacates.

This logic rests on a set of narrow and deeply distorted assumptions. Governments often understand choice as the ability to select between options, irrespective of whether those options are viable, affordable, or sustainable. In health policy, this takes the form of a lack of interest in structural forces combined with a growing insistence that individuals must manage risk more effectively. Inequality, in this telling, is not produced. It is merely revealed.

Yet this vision of freedom is profoundly misleading. Choice is never exercised in a vacuum. It is shaped by income, constrained by housing, filtered through education, eroded by chronic stress, and limited by time. To ignore these realities is to obscure power. When conservatives insist that health is a matter of personal responsibility while dismantling the conditions that make healthy lives possible, freedom becomes a rhetorical shield for abdication.

The language of choice dominates contemporary health policy. People are urged to eat better, exercise more, engage with digital tools, and self-manage increasingly complex conditions. These exhortations are often presented as empowering, even progressive. But empowerment without material support is a hollow promise. It transfers burden without transferring power.

A major new umbrella review of public health interventions across high-income countries lays bare the consequences of this approach. Examining evidence from thirty-five systematic reviews, covering welfare policy, housing, legislation, health systems, education, and digital health, the findings are remarkably consistent. Interventions that reduce health inequity most reliably are those that require the least individual effort and deliver protection automatically. Welfare support, housing provision, smoke-free legislation, and pharmaceutical cost regulation consistently narrow health gaps across socioeconomic lines.

These interventions work precisely because they do not rely on sustained individual agency.

By contrast, interventions that demand high levels of personal engagement, particularly educational, behavioral, and digital programs, produce weaker and more uneven effects. In many cases, they actively widen inequalities. This is not because such interventions are intrinsically flawed, but because their benefits accrue disproportionately to those who already possess time, stability, and resources. When policy assumes capacity that many do not have, it reproduces the very disparities it claims to address.

High-income countries often describe health inequalities as stubborn or residual, as though they persist despite good-faith efforts to resolve them. This language is revealing. It suggests that inequity is an unfortunate remainder rather than the predictable outcome of political choices. The evidence tells a different story. When governments act upstream, inequities narrow. When they retreat, inequities widen.

Nowhere is this misdiagnosis more pronounced than in North America, where health is routinely framed as an individual investment rather than a collective good. Insurance coverage may expand, but costs remain prohibitive. Digital health tools proliferate, but access remains uneven. Responsibility is devolved downward, while structural drivers remain intact. The result is a paradox: societies that celebrate freedom preside over some of the steepest health gradients in the world.

The umbrella review demonstrates that this pattern is not accidental. It is the consequence of privileging interventions that preserve market logic over those that redistribute risk. Housing vouchers reduce childhood illness. Income support lowers hospitalization. Legislative regulation narrows exposure to harm. These interventions succeed not by changing behavior directly, but by changing the conditions in which behavior occurs. That is precisely why they are politically contested.

The Health Equity Pyramid, developed within the review, offers a clear way to understand why certain policies succeed while others fail. At its base sit interventions that reshape the social and economic foundations of health. Welfare, housing, and regulation operate at population scale, require minimal individual effort, and deliver the greatest equity gains. As one moves up the pyramid, interventions become more individualized, more conditional, and more demanding. Their reach narrows, and their equity impact diminishes.

This framework exposes a central contradiction in contemporary policymaking. Governments increasingly favor interventions at the top of the pyramid, precisely where effectiveness is weakest and inequity risk is highest. These policies are politically attractive because they preserve the appearance of action without challenging underlying distributions of power or resources. They also align neatly with narratives of responsibility and merit. But they are poorly suited to addressing structural disadvantage.

Crucially, the review shows that high-agency interventions are not inherently futile. When carefully tailored, embedded within supportive systems, and targeted at specific disadvantaged groups, they can deliver meaningful benefits. The problem arises when such interventions are deployed as substitutes for structural reform rather than complements to it.

It is important to distinguish between inequality and inequity. Inequality describes difference. Inequity describes injustice. Not all variation in health is unfair: age, biology, and chance all play a role. But when life expectancy diverges by a decade along income lines, when preventable conditions concentrate predictably among the poorest, and when policy decisions consistently favor those already advantaged, the issue is not difference but injustice.

The umbrella review makes clear that inequity is produced through policy choices. It is not an inevitable by-product of complexity, nor an unfortunate residue of individual behavior. It narrows when governments redistribute, regulate, and protect. It widens when they withdraw, individualize, and moralize. This distinction matters because it clarifies responsibility. If inequity is produced, it can also be dismantled.

The costs of continued misdiagnosis are immense. Health inequities impose profound social and economic burdens, straining health systems, reducing productivity, and entrenching disadvantage across generations. Persisting with high-agency solutions while neglecting structural reform is not merely inefficient. It is actively harmful.

The focus must shift decisively: away from blaming individuals for navigating hostile environments; away from fetishizing choice while withdrawing support; away from digital solutions that obscure material deprivation; and toward policies that make healthy lives the default, not the reward for exceptional effort.

This requires restoring welfare as a health intervention, treating housing as essential infrastructure, regulating markets that profit from harm, and designing health systems that absorb risk rather than redistribute it downward. Above all, it requires rejecting the comforting fiction that freedom can exist without collective responsibility.

States that retreat from their duties do not create free citizens. They create unequal ones. And until high-income countries confront this reality, they will continue to misdiagnose inequity, prescribe the wrong solutions, and wonder: Why does the gap keep widening?