The Case for Universal Music Literacy

An ideal society would equitably distribute the means of production, and that includes musical production. Universal music literacy would ensure everyone has the tools to take part in the collective human legacy of music.

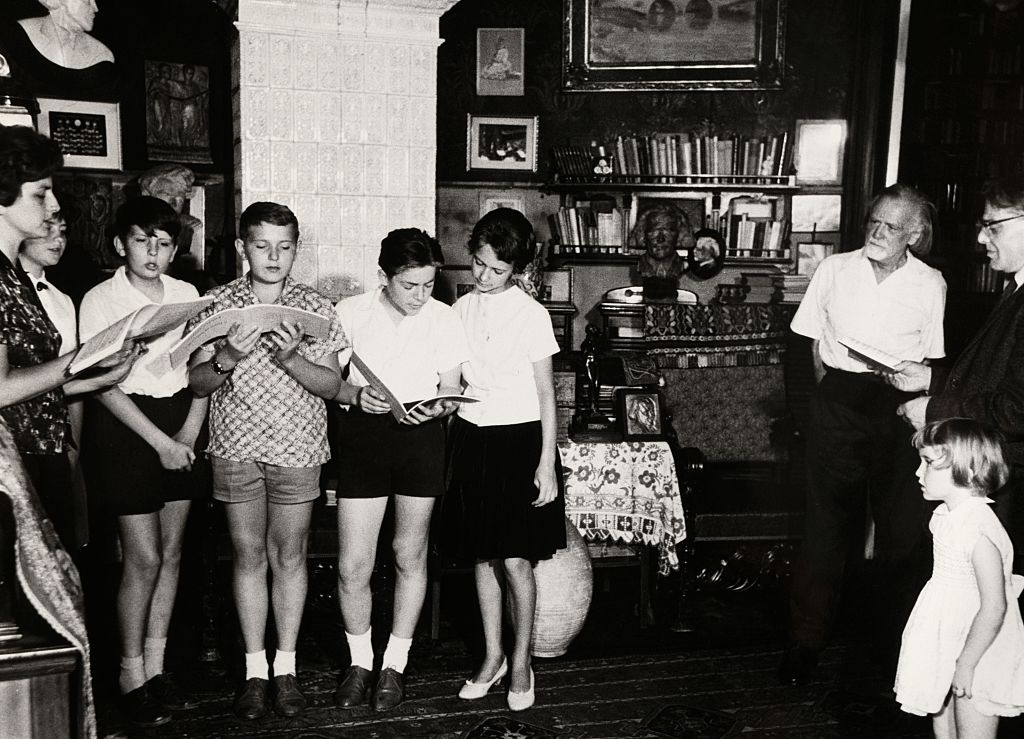

Music belongs to everyone. This principle, which was at the root of a socialist campaign to democratize musicianship in Hungary after World War II, should be part of a push for universal music literacy today. (DeAgostini / Getty Images)

Music making is a social achievement. Its technical skills are reproduced and disseminated through communities of musicians, its instruments are products of industry, and its performance routinely involves coordinated, collaborative effort. While a guitar or piano is often a musician’s own, the means of musical production far exceed the bounds of personal property. Music depends on its institutions: its libraries, conservatories, production companies, labels, and venues. Much depends on whether these are in private or public hands. For this reason, the question of socialism is especially salient in music.

It is hardly utopian to insist that a musically prosperous society offer its members the opportunity to participate in classical and vernacular music in civic choirs, orchestras, bands, and musical theater ensembles. Anyone with talent and inclination should count on society’s resources to foster specialized performance and composition skills. The wealth of our musical knowledge, historical and theoretical, ought continuously to expand through research and be made widely accessible through public education and media. Socialist planning could build large-scale musical infrastructure in the form of festivals, competitions, and conservatories, and thereby expand the proportion of our musical means owned collectively.

The indispensable foundation for any such system is music literacy. Socialists today should aim to make it universal.

Singing Socialism

This goal is not new. In their evangelical zeal, early modern Protestant movements often prioritized the reading of music. Shape note singing in the United States continues to embody this spirit. In the 1840s — the same decade that saw Karl Marx pen his anthropological manuscripts and Heinrich Heine the first proletarian lyric — the English Congregationalist minister John Curwen began an effective and consequential music literacy campaign aimed at the then emerging class of propertyless wage workers.

Singing has attended revolutionary politics since, at least, the eighteenth century. Uniting diverse and independent voices in harmony through cooperation, self-organization, and discipline is both a musical value and an irresistible political symbol. The democratic movements that overthrew feudalism in Europe inspired the formation of music making ensembles, especially choirs. Working-class struggle inherited the tradition. Meetings of the International Workingmen’s Association included the singing of songs, and the institution of the workers’ chorus epitomized the participatory culture of the Second International.

One of the most significant attempts to universalize music literacy took place in Hungary in the last century. It is tied up with the legacy of socialism in that country and centers on the career of teacher, composer, and ethnomusicologist Zoltán Kodály (1882–1967).

Kodály, the son of a provincial railway official who rose to prominence in the capital by dint of his prodigious talent, might well have matured into bourgeois liberalism. However, given the political alliance between Hungary’s landed aristocracy and the liberal intelligentsia in Budapest in the years before World War I, Kodály was led to embrace the peasantry, its agency and traditions, as the basis for a genuinely democratic national culture. Accordingly, he undertook to collect, record, and analyze hundreds of folk songs and dances.

His early career coincided with the end of World War I and the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In 1919, at the age of thirty-six, he found himself appointed to the Music Directory by the People’s Commissariat for Education and Culture alongside Béla Bartók, an internationally renown modernist composer. The commissariat was the arm of the Hungarian Soviet Republic which, fired by the Bolshevik example in Russia, sustained a proletarian dictatorship in the former kingdom for one hundred and thirty-three days before it was overwhelmed by superior Czechoslovak and Romanian forces. This brief experience in crafting socialist music policy with an eye to “bringing music and the people closer together” informed and animated the rest of Kodály’s career.

The counterrevolution that followed brought about a public inquiry into Kodály’s political allegiances. Counts brought against him included facilitating a performance of “The Internationale” and permitting Red Army recruitment at the Academy of Music. The intercession of friends, Bartók in particular, spared Kodály the brunt of white terror. In the years that followed, he leveraged his increasingly important status abroad to protect his efforts to promote music literacy in Hungary. The latter bore fruit in the form of the “Singing Youth” movement and in numerous pedagogical compositions.

However, it was only with the establishment of socialism in Hungary after World War II that Kodály’s leadership could finally count on sustained state support. What had been a movement was now a policy to musicalize a nation. His method was integrated into the public education system as a core subject, rather than an extracurricular activity. New music educators were formally trained in the method, and those already practicing music education were retrained in state-sponsored programs. The nationalized press published the necessary materials, and school choirs could be heard on radio broadcasts throughout the country. Music entered daily life as singing groups emerged in communities and workplaces.

Forces of Musical Production

Kodály was not steeped in Marxism, but he was nevertheless focused on developing music’s productive forces. He wrote that in Hungary, “the transition from a culture founded on oral tradition to a culture based on a written tradition has long since taken place . . . in literature, [while] in music we still have one foot in a purely oral culture. Thus, unless we want to be left behind for good, there is no more urgent task confronting us than to make this transition in music also.”

His broad historical vision was well-suited to the prevailing policy discourse of the time. In 1949, he proposed that “a five-year plan should be fixed for the complete extermination of [musical] illiteracy. In five years, it would be possible to achieve a situation where everyone could read at a level appropriate to his age.”

Believing the human voice to be the basis of our musical faculties, Kodály centered his method on solfège, the “do-re-mi” system, which has been essential to music literacy for more than a thousand years. It exists to facilitate the invention, reproduction, and transmission of melodies. By deciding the number and position of available notes, it creates a space for making good musical sense without any pretense to refined performance.

Mastery of the system encourages demotic musical utterances from children’s games to trade union hymnody. More important, just as the ability to draw teaches the eye to see, solfège trains the ear to hear, literally making the world more audible.

By synthesizing political and economic life, socialism makes it possible for a self-governing society to make intentional decisions about the division of labor. Some productive skills, like the basics of making music — and, perhaps, also of drawing and cooking — are put to most efficient use as general knowledge. The goal, as ever, is the equitable distribution of the means of production.

Hungary’s socialized music making system flourished for decades after Kodály’s death but fell into decline after the fall of communism. While his method resonates in classrooms around the world, the principle that drove his project — that music belongs to everyone — has languished. Socialists today do well to pick up on his legacy and prioritize literacy and infrastructure when articulating arts policy.