Liechtenstein’s Feudal Prince Has Become a Libertarian Hero

Hans-Adam II is Europe’s richest monarch despite ruling one of its tiniest states. The prince of Liechtenstein flaunts his contempt for democracy, blending feudalism and financial capitalism to supply a model for the Right in much bigger countries.

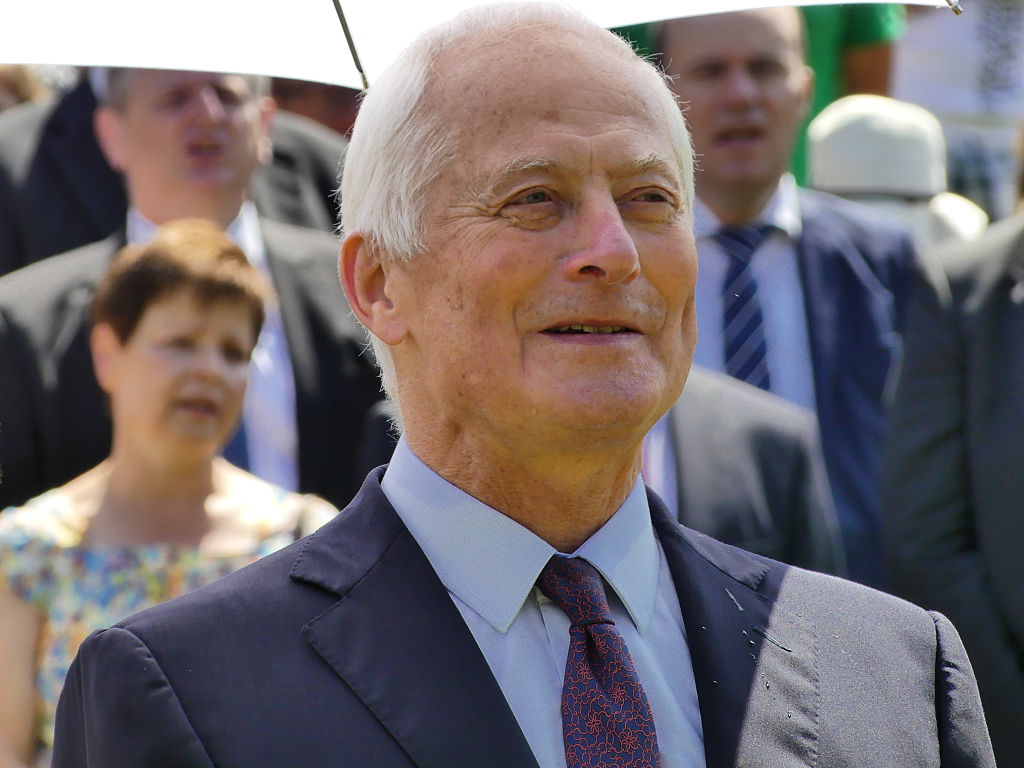

By combining Liechtenstein’s feudal heritage with his libertarian ideas, Prince Hans-Adam II has paved the way for a form of capitalism that is now very much in vogue, especially among the right-wing tech moguls who are trying to reshape the political landscape. (API / Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images)

In February 2025, the Principality of Liechtenstein, a microstate twenty-five kilometers long and twelve kilometers wide that is wedged between Switzerland and Austria, proudly celebrated the eightieth birthday of its reigning prince, Hans-Adam II. This ruler of a mountainous territory with just 41,000 inhabitants has become Europe’s wealthiest monarch — a man whose estimated fortune amounts to $12.6 billion.

Officially, the sovereign has retired from governmental affairs, having transferred his powers to his eldest son, Alois, in 2004. Yet Hans-Adam has left his mark on the history of this small country, transforming its institutions and its economy. In doing so, he has established it as a model for the libertarian right in some of the world’s biggest states.

On the rare occasions when Liechtenstein attracts the notice of the international media, it tends to be the subject of quirky stories about its modest size. In 2007, a small group of Swiss soldiers invaded the country by mistake after getting lost on a training exercise and retreated across the border once they realized where they were. This was one of several accidental incursions by Swiss forces over the years. There is no danger of a war resulting from such mishaps, as Liechtenstein has no army.

Nor does it have an airport, although there is a single railway line, which joins together the Swiss and Austrian networks. The national soccer team is one of Europe’s perennial whipping boys: in their recent World Cup qualifying group, Liechtenstein came last once again, having lost all their games without scoring a single goal. A 2020 quiz from the New York Times highlighted the country’s record of winning ten Olympic medals, all in the field of alpine skiing, and its status as a world leader in the production of false teeth.

Yet Liechtenstein’s significance for global capitalism is much greater than one might imagine from such miscellaneous details. By combining his country’s feudal heritage with his libertarian ideas, Hans-Adam has paved the way for a form of capitalism that is now very much in vogue, especially among the right-wing tech moguls who are trying to reshape the political landscape.

Feudal Remnant

Liechtenstein is a remnant of Europe’s feudal age. This small territory takes its name from the Austrian family that bought it in the early eighteenth century. Very close to the Habsburgs, the heirs of the House of Liechtenstein obtained the status of “sovereign prince” thanks to these 160 square kilometers on the banks of the Rhine.

However, the life of the house and its princes unfolded elsewhere. As big landowners with holdings in Austria and Bohemia, the princes lived in a sumptuous palace in the heart of Vienna, which visitors can still admire today. It was not until 1938, when Nazi Germany invaded Austria, that the family took refuge in Vaduz, the capital of Liechtenstein.

At the time, this territory was under Swiss influence, having signed a customs and monetary union with its larger neighbor in 1924. Adolf Hitler left it alone at the time of the Anschluss because of this relationship. But the interests of the family were not limited to the principality. The Liechtensteins were rich — very rich.

They possessed considerable assets in Austria and controlled a bank that they had acquired in the 1930s. In the 1970s, Hans-Adam, who was then still waiting to succeed his father Franz Joseph II as monarch, realized that he could take advantage of his family’s dual nature as a political power and a financial empire.

To achieve this goal, the prince, who became regent in 1984 before ascending to the throne in 1989, needed to shake off Swiss tutelage. He had to become the monarch of a fully sovereign country in order to lay down the rules that would benefit his business interests. In 1970, when he was only twenty-five years old, he gave a famous speech denouncing the state of affairs in which his country was “carried in Switzerland’s backpack.”

A Sovereign State

His first step was to apply for membership of the United Nations, which Liechtenstein obtained in 1990. From then on, the country’s ruler was a head of state who could speak on equal terms with others and possessed a voice in the UN General Assembly. The second stage of this strategy came in 1993, when the prince campaigned for his statelet to join the European Economic Area (EEA), placing it inside the European single market.

Hans-Adam insisted that the government should hold the referendum on EEA membership before the people of Switzerland voted, as Swiss public opinion was leaning toward rejection. However, according to the 1921 constitution which was then in force, this decision was not within the prince’s powers, and the government refused to give in. Unthinkably, demonstrations were held in Vaduz against the prince’s “dictatorship.”

In the end, the inhabitants of the principality accepted EEA membership, while the Swiss rejected it. Hans-Adam won out as Liechtenstein benefited from access to the European and Swiss markets alike and from the stability of the Swiss franc. Today it is the most industrialized country in the world, with 38 percent of its added value coming from manufacturing. It is also the world’s second-richest country, behind Monaco, with a GDP per capita of $219,000.

However, this victory still left Hans-Adam with a bitter taste in his mouth. What would happen if, one day, the people were to go against him? That would be unacceptable, not only for his status as sovereign but also and above all for his business interests. For behind the assertion of the country’s sovereignty, Hans-Adam remains a businessman.

Building an Empire

In the 1980s, he began to develop the Liechtenstein Global Trust (LGT) banking group abroad. He seized on his country’s potential as a tax haven arising from the “Treuhand” system, which facilitates trusts that conceal the true beneficiary of the funds.

If it was going to expand, this activity could not remain in the shadow of Swiss banks. EEA membership ensured free movement of capital between Liechtenstein and other European states, attracting the continent’s wealthy elites. LGT became the linchpin of the system.

At the same time, Liechtenstein’s status as a sovereign state allowed Hans-Adam to launch a challenge to the Beneš decrees, which had expropriated German landowners in Czechoslovakia without compensation in 1945. The House of Liechtenstein was one of the main landowners in the region and lost everything.

Hans-Adam has been obsessed with getting his land back, or at least obtaining compensation that would supply another boost to his business empire. As the head of state of a sovereign country, he could now challenge the expropriation of his family’s estates. In 2020, the Liechtenstein government even brought a case against the Beneš decrees before the European Court of Human Rights.

The Princely Initiative

These examples illustrate the logic of Hans-Adam’s thinking. He sees Liechtenstein as a possession of his family, who can make use of it like any other asset. Although he is willing to concede the idea of democracy on paper, his own will must determine its limits.

The prince’s approach is therefore that of a majority shareholder. He will listen to his staff and let them manage the details of how the country is run, but when it comes to the big picture — the decisions he considers important — he must have the final say.

The events of 1993 showed that he could be defeated, so he proposed a major constitutional reform in 2002. This reform would give him the power of veto over all laws and the appointment of judges. The prince engaged in open blackmail by threatening that his family would “return to Vienna” if the proposal was rejected.

The logic was still that of a business: since Liechtenstein was bought, it could also be sold if one is no longer satisfied with the owner. The referendum campaign over the “Princely Initiative” deeply divided this normally peaceful country. During a session of the Liechtenstein parliament, its speaker panicked and blurted out, “Without the prince, we are nothing.”

By the Grace of the Prince

When the referendum took place in March 2003, Hans-Adam’s reform won by a margin of 64 to 36 percent. A little under 15,000 people — about 87 percent of registered voters — took part in the exercise. Hans-Adam had won the day.

The following year, he handed over his day-to-day governmental duties to his son, while remaining the family patriarch. He divided the empire among his three sons, assigning Alois to manage the country, Max to manage the LGT financial group, and Constantin (who died in 2023) to manage the rest of the estate. Running the principality is thus just one of the family’s many activities.

In Liechtenstein, nobody challenges the prince’s power, with blackmail having done its job. Another referendum was held in 2012 after the prince pledged to block the legalization of abortion. This time, 76 percent of voters rejected a proposal to roll back the monarchy’s veto powers.

This small, wealthy country is, as one of its inhabitants told me, a “democracy by the grace of the prince.” Elections are held; the parliament legislates. But everything stays within the limits of what is acceptable to the princely family — that is to say, within the limits of its material interests. The voice of one man can override all others.

Trust Fund Economy

Those material interests have evolved over time. In 2009, the country faced a crisis after a whistleblower handed over documents to the German authorities revealing the extent of tax evasion in Liechtenstein. After initially resisting, Prince Alois finally abandoned the strategy of relying on dirty money.

Today Liechtenstein is no longer really a tax haven. Its justice system cooperates with foreign authorities, and it has signed tax agreements with the major Western countries. But the ruling family has not abandoned its financial ambitions.

Under Max’s leadership, LGT has transformed itself into a private bank, targeting wealthy clients with the promise that it will manage their funds as it manages those of the princely family. The bank has been successful, showing strong growth in Asia in particular. As of June this year, it was managing nearly 360 billion Swiss francs in assets (about $450 billion) and had offices in fifteen different countries, from Ireland and Spain to Singapore and the United Arab Emirates.

Hans-Adam is no mere figurehead prince. He is much wealthier and much more powerful than Britain’s Charles III, with a fortune of $12.6 billion, according to Bloomberg. This is 25 percent more than the annual GDP of “his” country, over which his family exercises complete control.

One, Two, Many Liechtensteins

The prince has developed a theory to support his political and economic practices, articulated in a book called The State in the Third Millennium. Hans-Adam sees the state as a “service company” based on a “partnership” between its owner — the prince himself — and the population, who must be “treated as customers.” In this framework, democracy is a way of managing private property, and the latter must always have the final say.

Hans-Adam’s thinking combines references to feudal tradition with the central role of capitalism in the management of the state. In the end, the veto of the prince-CEO also represents the open institutional sanction of capital’s tutelage over democracy.

Hans-Adam has never hidden his libertarian leanings. He believes that territorial fragmentation is a guarantee of good management because it drives states to compete with each other, reducing them to the status of “service companies.” The 2003 constitutional reform thus granted the right of secession to the municipalities of Liechtenstein, each of which have at most a few thousand inhabitants.

The prince of Liechtenstein’s actions have not gone unnoticed in libertarian circles. The German-born economist Hans-Hermann Hoppe, a disciple of Murray Rothbard, has made this country a model for his idea that monarchy is superior to democracy when it comes to “freedom.”

In 2022, Hoppe spoke about his dream of “a Europe of 1,000 Liechtensteins,” which closely resembles the vision expressed by Peter Thiel: “If we want to advance freedom, we need to increase the number of countries.” Argentina’s far-right president, Javier Milei, has described Hoppe and Rothbard as his main sources of inspiration.

Anarcho-Feudalism

What Hoppe finds most desirable about Liechtenstein is the fact that its state is entirely privately owned. As Hans-Adam points out in his book: “The costs of our monarchy, unlike all other monarchies, are covered by the private funds of the princely family.” The prince does not live off taxes; on the contrary, he supports the state, which is his patrimony. This is what makes this monarchy a form of “anarcho-capitalism.” Everywhere power is private and linked to property — in other words, to money.

In his 2001 book, Democracy: The God That Failed, Hoppe argued (against all historical evidence) that the transition from monarchy to democracy constituted a decline, because the monarchs took care of their private patrimonies and therefore tended to avoid imposing taxes and promote economic development. The ideal monarchy described by Hoppe resembles Hans-Adam’s Liechtenstein: the monarch does not need taxes to support himself because he runs his own business, whereas the leader of a democracy “lives” off taxes and therefore tends to increase them.

While the prince of Liechtenstein has never quoted a libertarian author in public, the similarities between his outlook and Hoppe’s thinking are striking. In 2020, another libertarian economist, Andrew Young, described Liechtenstein as the “the most tolerable form of state in existence today” in a journal article for the Mises Institute.

Hans-Adam has thus helped to design a new type of state, one that merges with the private sector around a monarchy of feudal origin. This example is reminiscent of the ideas of Curtis Yarvin, which are now inspiring Silicon Valley. Amid the current rise of capitalist authoritarianism, this little Alpine prince seems to be showing the way to the far right — a path in which democracy becomes a meaningless ritual.