Japan’s Liberal Democratic Party Faces an Identity Crisis

From its origins in 1955 as a US-sponsored bulwark against the Left, the conservative Liberal Democratic Party has dominated Japanese politics for seven decades. It now faces a new electoral challenge from parties of the populist, xenophobic right.

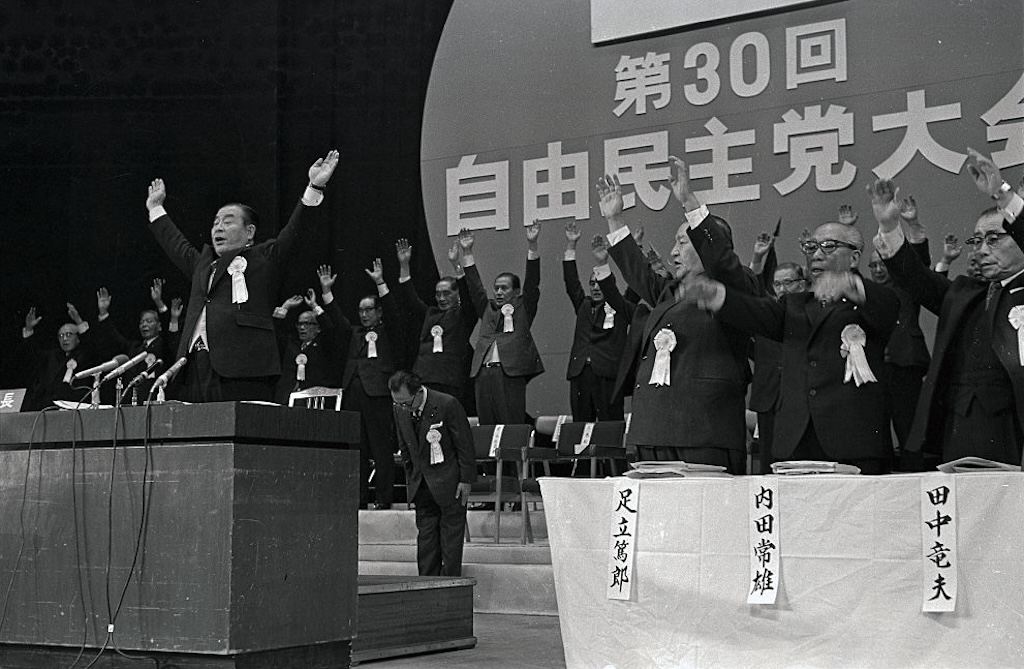

Japan’s Liberal Democratic Party is easily the most successful political party in the developed capitalist world. With its dominance now strongly contested by elements to its right, the LDP is struggling to adapt. (Bettmann / Getty Images)

Japan’s Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) is easily the most successful political party in the developed capitalist world. While other long-standing parties of government have gone into crisis and decline, from the Italian Christian Democrats to Ireland’s Fianna Fáil, the LDP has retained its position at the head of the Japanese state through all the transformations that its society has undergone over the past seven decades.

The LDP was established in November 1955, shortly after the reunification of the Japan Socialist Party (JSP) the previous month. One of the senior architects of the conservative merger commented that the new party, with its diverse and conflicting factions, would be lucky to survive ten years. Instead, the LDP went on to become the dominant ruling party throughout the Cold War and beyond.

After retaining its mantle as the ruling party for thirty-eight continuous years, the LDP was ousted from power in 1993 and again in 2009. After both electoral defeats, commentators proclaimed the long-awaited demise of an anachronistic and corrupt party. Such pronouncements proved to be premature.

Thanks to successful adaptations by the LDP itself and the failure of rival parties to capitalize on their own political mandates, the LDP reemerged as dominant as ever. However, recent scandals have led to another decline in LDP support. The party is now a minority force in both houses of parliament after electoral setbacks during the past two years.

Origins

The LDP’s name is misleading. It is neither particularly “liberal” nor “democratic” in nature, nor is it a typical “party” with a coherent leadership structure. It started as a conservative alliance against socialism and communism, uniting around the Cold War rallying cry of “freedom and democracy.”

The LDP was, first and foremost, a pro–big business coalition to stem the rise of the union-backed JSP. However, it avoided defining itself as such and stressed that it would be a “national party” that would promote the welfare of the entire nation, unlike its leftist rivals promoting parochial class interests.

The LDP’s emphasis on its “national” position reflected a weakness of the conservative camp at the time of its founding. Its support for Japan’s alliance with the United States invited nationalist criticisms over “subordinate independence” that allowed the continued presence of US troops on Japanese land. Throughout the 1950s, the LDP remained vulnerable to such criticisms from the nationalist left.

The LDP’s “national” stance also stemmed from the fact that, while big business could provide financial support, it could not deliver votes in the same way as the unions. The LDP sought to expand its support base to encompass all nonunionized Japanese voters.

Despite its emphasis on becoming a broad-based national party, the LDP could not conceal its reactionary agenda during the first five years after its establishment. The party sought to undo the reforms intended to demilitarize and democratize Japan that had been carried out under US occupation by revising the US-Japan Security Treaty and the postwar constitution.

Kishi Nobusuke, the former class-A war criminal who became prime minister in 1957, led the effort to revise the Security Treaty. However, his initiative unleashed a massive wave of popular protests. The revised treaty was ratified, but Dwight Eisenhower’s celebratory visit to Tokyo was canceled. Kishi had to resign, and the LDP shelved its goal of revising the constitution.

Rapid Economic Growth

After Kishi’s resignation, Ikeda Hayato became prime minister and announced his “income-doubling plan.” A former bureaucrat with a reputation for arrogance and politically insensitive remarks, Ikeda remade his public image by adopting a softer fashion style and abstaining from golf and geisha parties. His transformation embodied the LDP’s full embrace of its identity as a broad-based national party.

The Kishi–Ikeda transition was the first of many shifts whereby the LDP would replace an unpopular prime minister with a fresh face representing change. This chameleon-like ability to change its look and adapt to new circumstances has been a key factor behind the LDP’s longevity as the dominant ruling party.

The first general election under Ikeda took place in November 1960, after Ikeda’s pledge to double the national income in ten years succeeded in capturing the national imagination. Unable to oppose the consensual goal of greater affluence, the JSP attempted to counter the LDP by aiming for even higher income levels. It also criticized the LDP’s proposal for offering inadequate support measures to protect farmers who would be left behind.

With successive victories in gubernatorial elections from the late 1950s, it had appeared that a farmer-worker alliance would solidify as a JSP-led opposition bloc. Facing a series of drastic budgetary cuts, farmers feared that national priorities were shifting away from them. The 1961 enactment of the Basic Law on Agriculture, which promoted higher productivity in the agricultural sector, further alarmed small farmers who felt they were being squeezed out of existence.

However, a series of negotiations between the JA (Japan Agricultural Cooperatives) and LDP members led to an agreement to prop up rice prices so as to manage the increasing imbalance in income levels between urban and rural areas. The context of rapid economic growth facilitated the LDP’s successful co-optation of leftist opposition in rural areas through generous budgetary support.

Stable support in rural regions became a key foundation of LDP power. This LDP advantage was reinforced by the effective devaluation of urban votes in relation to rural ones due to districting rules that were not adjusted in spite of a major demographic shift into the big cities.

After Rapid Economic Growth

Rapid economic growth enabled LDP dominance. It also set in motion social changes that would undermine it. The LDP’s share of votes in general elections continually declined and dipped below 50 percent for the first time in 1967.

A major factor behind this trend was the rapid shift from primary to secondary and tertiary industries, and the attendant demographic shift into cities. While the radicalized JSP largely failed to capitalize on this, a new party, Kōmeitō, won twenty-five seats with more than 5 percent of the vote in the 1967 election. The Japanese Communist Party (JCP) received almost as many votes as Kōmeitō, although it only won five seats.

The most notable progressive victories were on the regional level. In April 1967, Minobe Ryōkichi won the Tokyo gubernatorial election with the support of the JSP and JCP. Minobe succeeded in becoming a progressive champion, pledging to combat the urban problems that the LDP’s rapid economic growth policies had precipitated. His electoral victory was followed by victories by other progressive mayors in other big cities, leading to an era of “progressive local governments.”

The LDP leader in charge of its committee on urban policy at this time was Tanaka Kakuei, a self-made politician from a rural background with construction industry roots who was known as the “computerized bulldozer.” He responded to Minobe’s electoral victory by vowing to build a new LDP that would win over the increasingly important urban voters.

Tanaka stressed that the LDP needed to promote a more balanced developmental model that would simultaneously alleviate urban and rural problems. In 1972, shortly before he became prime minister, he published a best-selling book promoting such a vision. He called for massive investments in rapid railway and highway construction, along with the repositioning of industrial facilities out of cities and into rural areas.

Drawing from the progressive policies that were being implemented by municipal governments, Tanaka’s book also advocated stronger regulation to combat pollution. Reactive adoption of progressive policies was an LDP pattern during the latter part of the period of rapid economic growth and after it ended. Examples ranged from the Satō administration’s antipollution legislation to the Tanaka administration’s progressive pension reform and provision of free medical care for the elderly. The LDP’s ability to accommodate and co-opt progressive demands was another key aspect of its ability to maintain its hold on power as a national party.

The LDP sought to become more like its progressive adversaries not only in terms of the policies it adopted, but also in the way it structured itself as a party organization. The loose, ad hoc manner in which the LDP coordinated between its disparate factions had been a concern for party leaders since the time of its founding. With electoral support trending ever downward, the party leadership once again considered how it could effectively reorganize itself to become a real party with a coherent leadership structure.

Changing the Rules

LDP leaders saw the multiple-seat constituency system as a major cause of the deep-rooted factional divisions that plagued the party. In a system where fellow LDP politicians had to compete against each other in parliamentary districts, the party headquarters had a diminished role, and LDP candidates needed to rely on its factions for support.

When the LDP attempted to pass legislation that would establish single-seat constituencies in 1956, the JSP pushed back, denouncing the proposed system as a “conspiracy to revise the constitution and maintain conservative rule.” Indeed, the winner-takes-all model was expected to deliver major electoral gains for the LDP, expanding its majority beyond the two-thirds level needed to revise the constitution.

The 1956 attempt at electoral reform ultimately failed in the face of a public outcry at the exposure of gerrymandering tactics. Even business organizations that supported the new system asked the administration to revise its blatantly partisan plan. Minority factions within the LDP also came out in opposition to the reform, which they thought would strengthen central authority in the party and have a silencing effect on dissenting voices.

When the Tanaka administration tried again in 1973, the result was similar. The planned redistricting was blatantly partisan in its details, provoking fierce opposition from minority opposition parties and critical reporting by the mass media. Cautious voices within the LDP warned that attempts to force through the partisan initiative would backfire.

In the end, Tanaka refrained from submitting the legislation to the Diet. A group of pro-LDP intellectuals grew so alarmed by these developments that they drafted a letter to the party, warning that the adoption of a single-seat system was the “only legal means remaining” to effectively protect LDP power against the “striking advance” of the JCP and JSP.

Over the ensuing years, the structural crisis of the LDP continued to deepen, as the oil shock ended rapid economic growth and triggered hyperinflation. Tanaka went all-in for his battle to win the 1974 upper house elections, vowing to “protect free society” against the Left. He chartered a helicopter to campaign throughout the nation, touting the benefits of more highways and bullet trains, distributing massive amounts of state funding, and mobilizing entire companies to deliver the votes of their workforces. However, these efforts only produced lackluster results.

As the LDP reeled from yet another poor electoral performance, a popular magazine published a bombshell article exposing Tanaka’s corruption. It explained the details of a practice that many had vaguely suspected was in operation.

There are two separate words in the domain of political funds: “open” (omote) money and “secret” (ura) money.The article demonstrated in meticulous detail how Tanaka had accumulated a massive amount of ura money and deployed it shamelessly to promote his political ends. it triggered a public outcry and forced Tanaka to step down, to be replaced by Miki Takeo, a factional antagonist with a clean reputation. Nevertheless, Tanaka continued to wield considerable power behind the scenes as the LDP’s “shadow shogun.”

The Short-Lived Two-Party System

In 1988, it came to light that Recruit, a job placement company, had gifted its pre-flotation shares to leading politicians and other influential people. The LDP prime minister Takeshita Noboru, a Tanaka protégé, was one of the politicians implicated in the scandal.

Takeshita sought to settle the issue by publicizing the fact that he had received direct and indirect donations totaling ¥151 million from Recruit, adding that he “did not expect at all” that there would be any additional revelations. The following week, a newspaper reported that Recruit had loaned ¥50 million to Takeshita’s campaign during the 1987 general elections. Takeshita resigned a few days later.

The Recruit scandal implicated almost all leading LDP politicians and led to reforms in the electoral system that were supposed to root out systemic corruption. Critics identified the multiple-seat system as a root cause of endemic corruption because it promoted money-driven factional competition within the LDP. The system was abolished and replaced with a single-seat model.

Unlike previous LDP efforts to change the system, this was not simply a blatant attempt to reinforce LDP dominance. Ozawa Ichirō, the LDP secretary general leading the reform, sought to establish a competitive two-party system. In his vision, the LDP would be one player, while the other would be a rival conservative party led by competent leaders like himself. For a brief period after the reforms, it appeared that the two-party system Ozawa envisioned would take root.

In 1996, the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) was established and quickly became the most popular party in Japan’s cities, where LDP support was weakest. The LDP appeared to be slipping back into the past, with the prime minister Mori Yoshirō vowing to make all Japanese recognize that Japan was “an emperor-centered land of the gods.” These remarks provoked a popular backlash and led to a LDP drubbing in the ensuing election, where urban and suburban voters gave strong support to the DPJ, despite Mori’s message encouraging them to stay in bed on election day.

The LDP’s fortunes were temporarily reversed under the ensuing leadership of Koizumi Jun’ichirō, a media-savvy politician known as “Lionheart” for his wavy long hair. Koizumi declared that he was going to “destroy the LDP.” Specifically, he set out to destroy the LDP factions and their pork-barrel spending that had supported uncompetitive regions and industries ever since the period of rapid economic growth.

Koizumi had a simple message. He was in favor of reforms to promote economic growth, and everybody who opposed such reforms belonged to the “resistance forces” who were trying to pull the country back into stagnation. His signature reform was the privatization of Japan’s postal system — a powerful vote-collecting machine and source of pork-barrel spending that Tanaka had constructed.

When some LDP members opposed this move, Koizumi dissolved the Diet and nominated “assassins” to defeat the LDP “postal rebels.” He appealed directly to voters to see the election as a referendum on his reform agenda. Koizumi’s LDP won a resounding victory.

The DPJ seemed to be effectively sidelined during Koizumi’s dominant performance. Behind the scenes, however, the opposition party was expanding its base into the countryside that Koizumi’s LDP was abandoning. Postmasters across the nation left the LDP, with many of them mobilizing to support the DPJ. Ozawa Ichirō, who joined the DPJ leadership in 2003, leveraged connections he had cultivated during his LDP years to expand its power base.

Such efforts bore fruit in the 2009 lower house election, in which the DPJ defeated the LDP by an overwhelming margin, winning in both urban and rural districts. While the LDP had suffered electoral defeats and failed to win majorities before, this was the first time that the party relinquished its position as the largest party.

The LDP under the new prime minister Abe Shinzō seemed to be backtracking from the Koizumi reforms, allowing the postal “rebels” to return to the party and alienating the urban voters who had been attracted by the reform agenda. At the same time, the party could no longer count on the rural support base that it had abandoned.

The DPJ appeared to have emerged as a full-fledged national party that would end LDP dominance. However, its short years in power were marked by a series of failures and crises, some of its own making, others resulting from events beyond its control.

Most notably, the DPJ was unable to effectively respond to the catastrophic nuclear meltdown in Fukushima caused by the March 2011 earthquake and tsunami. While the LDP response might not have been much better, public disenchantment over a seemingly incompetent DPJ leadership resulted. After Abe Shinzō returned to power in 2012, he frequently invoked the “nightmarish” past of DPJ misrule.

During his first administration, Abe’s conservative message to “take back Japan” largely fell flat. In his second administration, he led with his “Abenomics,” centered around an aggressive approach to monetary and fiscal policy and pro-growth reforms. With the public generally won over by Abenomics, Abe pushed ahead with his political agenda, passing controversial legislation expanding the ability of Japan’s Self-Defense Forces to operate overseas. While Abe’s bill triggered protests outside the Diet, his approval ratings remained stable.

Public support for the Abe administration declined in 2017 after a series of corruption scandals. Even so, there was a group of “bedrock conservatives” that continued to support the Abe administration. These conservatives were not the rural groups that had formed the LDP’s political support base during the period of rapid economic growth. Rather, they were the right-wing cultural conservatives that the LDP had relied upon to stage its political comeback from its brief years out of power from 2009.

The DPJ opposition, meanwhile, was plagued by divisions over Abe’s security law and cooperation with the JCP. It underwent successive splits that left it significantly weakened and has now been rebranded as the Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan (CDP).

The LDP’s Recent Setbacks

Since Abe stepped down in 2020, there have been two major revelations that damaged support for the LDP. The first concerned the LDP’s close ties with the Unification Church, which came to light after Abe was assassinated by a man whose family had been victimized by the church. The LDP refused to conduct a substantive investigation into the issue and pushed ahead with a controversial state funeral for Abe, which led to a decline in support for the administration.

The second was yet another money scandal. In late November 2022, the JCP newspaper Akahata reported on the Abe faction’s illegal political fundraising practices. About a year elapsed before the problem developed into a full-blown scandal that received the full attention of the mainstream media. When it did, the public was aghast to learn that the political reforms after the Recruit scandal had done little to root out systemic corruption in the LDP.

The LDP attempted to salvage the situation with another change in leadership. Ishiba Shigeru, an LDP leader who had been an increasingly isolated figure within the party for his refusal to fall in line with Abe’s policies, was chosen to lead it out of its hole. He proved unable to do so, with voters increasingly frustrated by government inaction in the face of surging inflation. Successive electoral defeats in 2024 and 2025 left the LDP as a minority party in both houses.

It was notable that the LDP’s most recent electoral defeat was not a victory for the liberal opposition. The CDP struggled, as did the JCP, while two new right-wing populist parties emerged as the biggest winners. The Democratic Party for the People gained support from working-age voters with its specific pledge to “increase net income.” The hard-right party Sanseitō surged, increasing its number of seats from two to fifteen, successfully pitching its “Japanese First” message to a swelling group of voters who feel abandoned by an out-of-touch ruling establishment.

Following customary practice, Ishiba announced his resignation after his two electoral defeats — but only after resisting and delaying for over a month. While he could be faulted for his lack of decisiveness, it was clear that Ishiba was not the main culprit for the LDP’s declining fortunes. When Abe-faction politicians and other party bosses began pressuring Ishiba to quickly step aside after the upper house election, it appeared to party outsiders that a relatively clean and trustworthy leader was being unfairly blamed.

Poll numbers showed public support for the Ishiba administration rising in the wake of the 2025 election. There were even demonstrators, many of them non-LDP supporters, who gathered outside the Diet to “encourage” Ishiba to not quit. A common sentiment shared by the demonstrators was that a post-Ishiba LDP would veer back to the right to regain the support of the “bedrock conservatives” it had lost under Ishiba. With opposition parties positioned to the right of the LDP gaining momentum, as “foreigners” become the main target for populist agitators, this is no idle concern.