The Rise of Chile’s Hard Right

The first round of voting in Chile’s general election in November saw the shocking rise of the far right and the collapse of the country’s new left. It’s a crushing but not total defeat for the movement helmed by President Gabriel Boric.

Presidential candidate Jose Antonio Kast on November 16, 2025, in Santiago. (Tamara Merino / Bloomberg via Getty Images)

On November 16, Chile held its first general election since former student movement leader Gabriel Boric won the 2021 presidential runoffs as a candidate of a promising new left coalition. This time, however, a hard right emerged as the country’s dominant political force. It is now set to cruise to a second-round victory in December, which would drive a national realignment favoring reactionary parties.

These were also the first elections since voters overwhelming rejected a proposal to replace the 1980 constitution, a charter imposed under military rule that enshrined core neoliberal principles and institutions. As with the 2022 constitutional plebiscite, mandatory voting turned out swaths of disaffected working-class voters whose pressing needs Boric’s Broad Front–Communist Party coalition government left largely unaddressed. Today they are seeking pragmatic solutions from the extreme right and anti-ideological demagogues.

The results amount to a devastating, though not definitive, blow to reform and socialist politics. Chile is now likely to be governed by an alliance between José Antonio Kast’s ultraconservative neo-authoritarian Partido Republicano (PR) and upstart Johannes Kaiser’s reactionary libertarian Partido Nacional Libertario. As the Cambio por Chile coalition pushes forward in reshaping the country’s party system and policy agenda, it has effectively subordinated the old center-right bloc that spent three decades co-governing with the now-dissolved center-left Concertación following the 1990 transition from dictatorship.

On the other side of the aisle, the Left has been thoroughly diminished, with the ascendant far right making significant inroads into working-class constituencies, including many voters that had previously supported Boric. However, the popular swing toward strident free-market and mano dura politics was far from unanimous. The Partido de la Gente (PDG), an “outsider” party led by a populist who rails against both the Right and Left in defense of commonsense “meritocratic” policies rattled the political class by placing third. Although the reactionary right hammered Chile’s progressives, many ordinary Chileans’ reticence to embrace neo-authoritarian extremism along with the voting base the new left managed to preserve offers some hope that it might learn to refashion itself into an effective and winning force for meaningful working-class reforms.

Looking Closer at the Vote

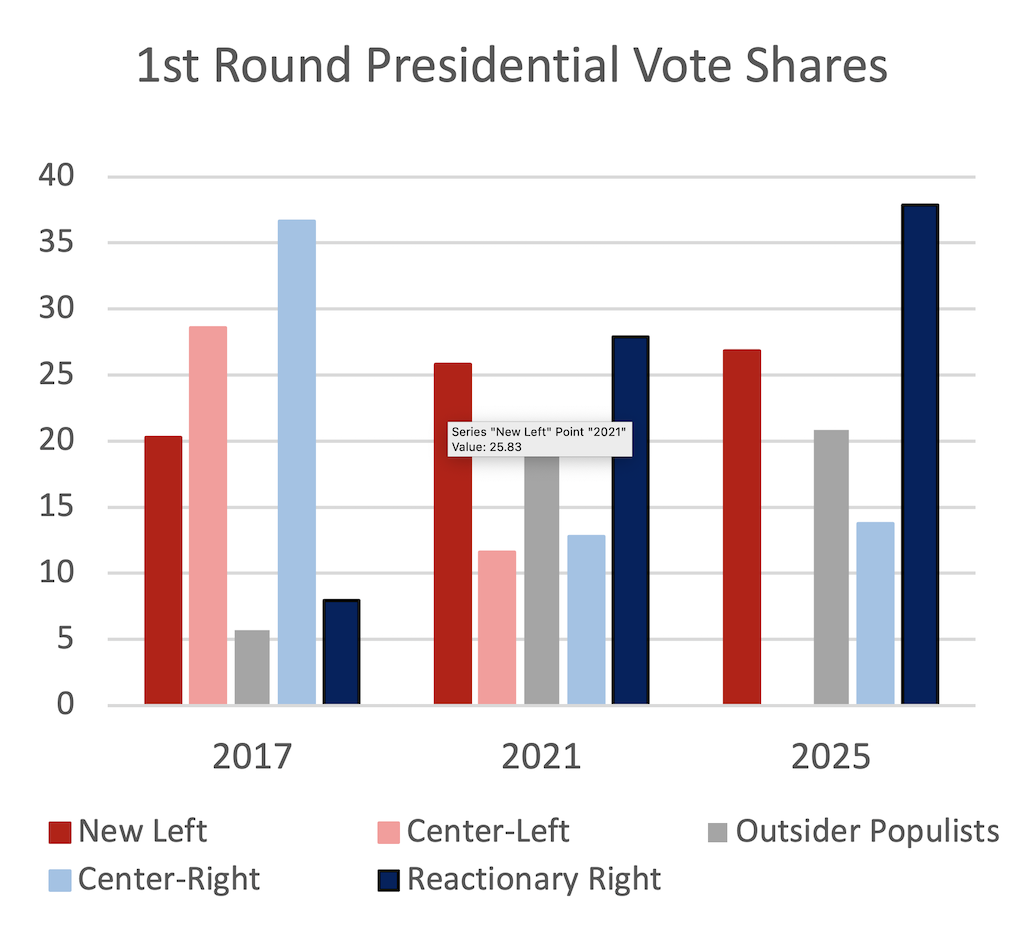

Five important coalitions and parties competed in this year’s general elections. The broad and diverse field suggests that Chile’s party system has definitively moved away from the centrist coalitions that dominated post-dictatorship. In 2021, six major candidates competed, ranging from the new left to the far right, including remnants of the centrist coalitions as well as two antiestablishment outsiders. That year, ultraconservative Kast took the top spot with 28 percent, and Boric followed with 26 percent. While the PDG’s “commonsense” demagogue, Franco Parisi, surprised everyone with 13 percent, no other candidate surpassed one-eighth of the vote.

Recognizing that it can no longer compete effectively in national elections, the once-dominant center left has since aligned itself with the new left alliance. Most of the remaining political spectrum entered these elections splintered. Other than Parisi and Marco Enríquez-Ominami, another populist seeking to replicate his 20 percent showing in 2009, three right-wing candidates hoped to establish a clear advantage in first-round voting. In addition to Kast and Kaiser, longtime politician Evelyn Matthei, who was thrashed by Michelle Bachelet in 2013, sought to consolidate a less extreme anti-progressive pole around the center right. Together with Parisi, right-wingers aimed their sights on the new left candidate, former labor minister Jeannette Jara.

Nearly all polls had the Communist Jara winning the first round with a comfortable plurality. Many predicted her support to settle somewhere around Boric’s approval ratings, which have been frozen at roughly one-third since the early months of his presidency. Polls also showed right-wingers trading places between second and fourth place, while relegating Parisi to under 5 percent. Whereas Jara’s anticipated top position held throughout the first round of voting, Parisi reached a shocking 19.7 percent with Augusto Pinochet apologist and market fundamentalist Kaiser’s finishing in fourth place — beating out the moderate Matthei — alarming both progressives and democrats. According to recent polling for the December 14 runoff election, Kast is now considered the front-runner.

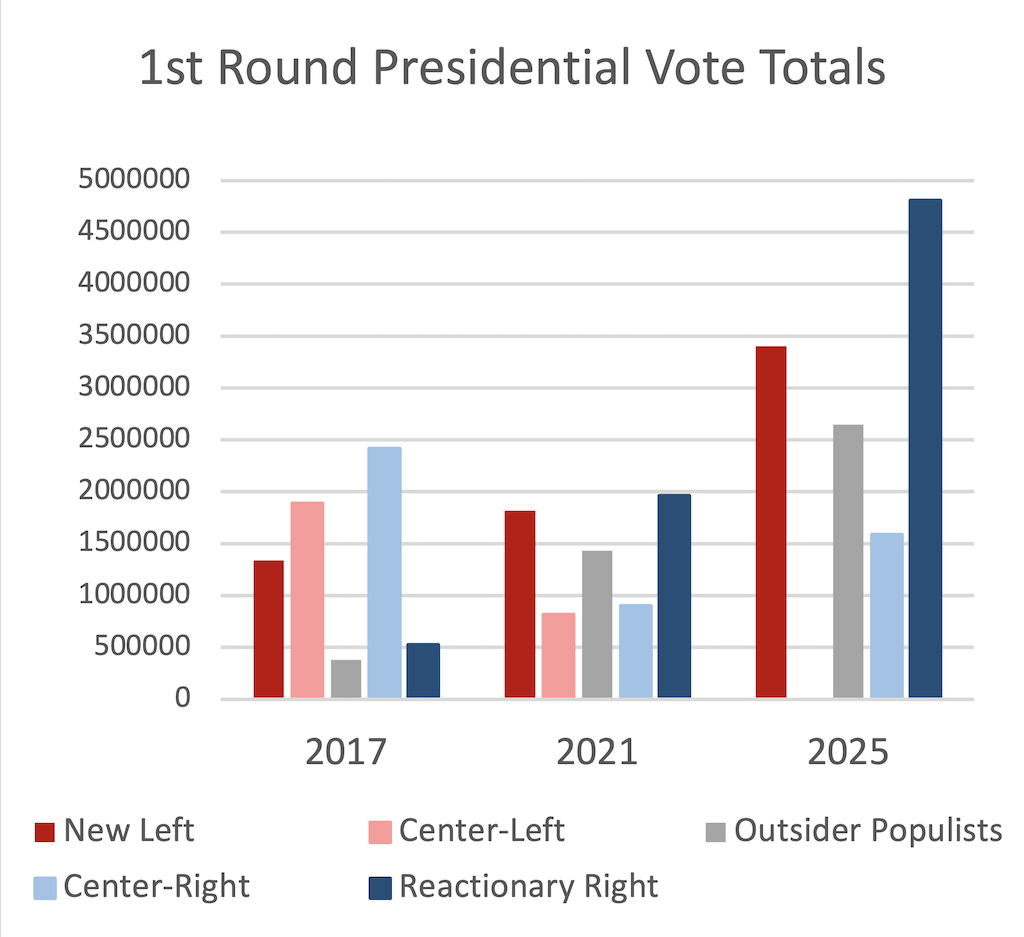

When compared to the last two national elections, the anti-progressive shift is undeniable. Shockingly, Jara barely edged out Kast in the first round with 27 to his 24 percent. Worse still, half of all voters cast their ballots for the three right-wingers. Even with Parisi’s unforeseen 19.7 percent, enough to overtake Kaiser and Matthei, the hard right can claim victory. In their breakout 2017 elections, left radicals won three times as many votes as Kast, who competed as an independent, though the centrist coalitions maintained their dominance. The following elections took place after Chile’s October 2019 mass rebellion, or estallido, and the formerly leading alliances, whose legitimacy had plummeted, saw their support fall to their lowest levels since re-democratization. The new left expanded its support in 2021, but bubbling frustration with the hyper-progressive constituent assembly amid the pandemic and an economic downturn boosted Kast to first place. This time around, the hard right, personified in Kast and his former coreligionist Kaiser, was the undisputed winner. While the broad left of center only marginally increased its percentage, votes for the hard right grew from a little more than a quarter to over a third of the electorate.

Absolute numbers reveal the same troubling story. After Chile’s 2022 adoption of mandatory voting, expanded turnouts were anticipated for all parties. Indeed, in one of these election’s silver linings, the new left nearly doubled its voters compared to 2021, garnering 3.4 million (or close to three times its 2017 votes). But the hard right’s total votes handily eclipsed the Left’s growth with a staggering 4.8 million votes, or almost 150 percent more than in 2021 and eight times more than in 2017. After new rules forced all Chileans to vote, it’s undeniable that an overwhelming proportion of absolute gains went to the extreme right.

For now, the Left’s disadvantage is insurmountable. Even if Jara somehow wins over the majority of Parisi voters in the runoff, victory is mathematically impossible. The runoff patterns from 2021 suggested that three-fourths of Parisi backers supported Boric in the second round. To stand a chance, Jara would need to hold onto all of them this time around, an outcome precluded both by runoff polling as well as the general anti-progressive tilt of today’s electorate. Beyond the arithmetic of Chile’s recent elections, the key to explaining the Left’s looming defeat is understanding the growing rejection of Boric’s coalition by ordinary Chilean voters.

Chile’s Economy Is Miserable for the Average Worker

The main factor behind the surging far right is ordinary Chileans’ disappointment with the new left’s record under President Boric. Disgruntled workers showed up at the ballot box to punish leftists just as they did when they decisively voted down the new constitution progressives drafted back in 2022. Only this time the rejection is deeper and more extensive, spreading now throughout the country’s provinces and penetrating far deeper into its primary working-class strongholds.

Boric’s Frente Amplio (FA) government was not without its victories. They managed to pass legislation providing undeniable relief for many working-class households. As minister of labor, Jara is credited for its central achievements — minimum wage increases, a forty-hour workweek, and the improvement of Chile’s retirement system. But these measures are a shadow of what the new left campaigned on in the aftermath of the estallido. The FA’s platform led with full nationalization of privatized pensions with substantially raised retirement floors, progressive tax reform, centralized collective bargaining, a universal public health care system, public investment in a national jobs program, and student debt forgiveness. It proposed nothing less than a total overhaul of Chilean neoliberalism.

Although the preceding decades of orthodox liberalization from 1990 to 2010 significantly reduced poverty — while leading to booming growth rates in the 1990s — Chile remained one of Latin America’s most unequal societies even under center-left governments. After four years in office, the new left’s accomplishments fall far short of addressing this dilemma. The measures currently being touted by Jara’s team pale next to the magnitude of working Chileans’ immediate needs. Most of the reforms on offer are paltry, with others being phased in over several years.

Even though average wages under Chile’s new left increased slightly, the employment landscape is still one of merciless insecurity for the average worker. Since the pandemic, unemployment has been stuck at around 10 percent. But even among those who find work, precarity is the norm. Today only about one-third of all employed Chileans enjoy full labor protections. Another 26 percent labor in the informal economy, while 43 percent work without reliable contracts.

Under Boric, labor markets only worsened for working Chileans. Of all jobs created since 2020, over 70 percent are unprotected. In a country where prior social spending just barely moved the needle on inequality, the new left has failed to make a notable difference. While Chile’s earlier growth period finally pushed the nation’s per capita GDP into the middle-income strata, median monthly income languishes at US$611 (with half of informal workers making under US$340). Presently, half of all wage earners cannot lift their families above the official poverty line.

So while wages have edged upward, Chilean workers’ ability to win concessions from employers remains unchanged. After the new government abandoned proposals to install centralized forms of industrywide collective bargaining, existing labor organizations remain weak. The one basic protection that was passed — a reduced workweek — does not come into full effect until 2028. Furthermore, the legislation opens a back door for increased labor flexibility. Its most damning gap is its failure to cover those without formal contracts, which in Chile is the vast majority of workers.

The government’s new pension system is similarly disappointing. “Guaranteed solidarity” pensions for the oldest retirees with low or no savings will grow by 10 percent, or a total of roughly US$25; and this marginal raise will not be available to sixty-five-year-old retirees until 2027. Most others will see increases of about US$100, as long as they have paid in for more than twenty years. The byzantine architecture of the reform is the key reason the elderly now feel cheated — although the new law raises employer contributions to a 7 percent rate, workers will still be asked to put aside 10 percent of wages to finance their retirement. Even then they must wait until 2033 for employer contributions to fully phase in. None of this remotely resembles the new left’s original plan for full socialization and universality. It is a patchwork of revenue streams that locks in means-tested welfare for the poorest and reinvigorates the private, financialized funds that hold the equivalent of 60 percent of Chile’s GDP and will continue to control the system.

In truth, the government abandoned its most ambitious plans once its proposed tax reform collapsed in 2023. Aiming to expand public revenues by 4.5 percent of GDP over several years by raising rates on mining exports and high earners — including a wealth tax — the legislation never made it to a lower house floor debate. As expected, pressure from the business lobby was fierce. But in the end, three abstentions from progressive legislators outside of the FA-CP alliance killed the bill.

The derailment of the new left’s anchor legislation reveals a key flaw in its reform strategy. On one hand, it reflects the coalition’s shaky congressional majorities. On the other hand, however, it betrays an unwillingness to mobilize supporters to turn up the heat on reluctant lawmakers. The new left’s disadvantage in both chambers came down to a handful of representatives on whom popular pressure just might have offset elite influence. Had such a strategy failed, it would at least have signaled a readiness to fight hard for working Chileans’ interests; simultaneously, it would have shored up rank-and-file organization for these inevitable conflicts.

To make matters worse, the Left settled into a sort of complacency, insisting on its progressive credentials rather than devising ways to mobilize constituents to counter business recalcitrance. The same FA platform highlighted the right to euthanasia, new gender identity legislation, and the implementation of a new sex education model. On their own, these measures did not repel ordinary Chileans — after all, those with entrenched ideological attachments to these positions would never have favored leftist reform.

Instead, sensing the government’s incapacity to deliver on core class-wide reforms that the estallido placed front and center, many resented what looked like a willingness to promote narrow identitarian issues at the expense of baseline material well-being. In fact, early in its tenure, the government staked its political fortunes on the 2022 constitutional referendum. Similarly viewed as a moralistic grab bag of particularist causes, the proposed charter became an albatross instead of a springboard. Over three-fifths of Chileans rejected what was to be the new left’s foundational achievement, largely owing to how removed it was from their core material concerns — not because they preferred Pinochet’s authoritarian constitution. The FA-CP alliance has been punished ever since for a perceived wavering on its commitment to prioritizing workers’ economic security.

If many left-leaning voters today are frustrated and waffling, new voters who have been alienated from politics for years constitute the core drivers of the current rightward shift. When changes in voting rules suddenly expanded the electorate, the new left was presented with a unique opportunity to win the sympathies of these disaffected workers. Yet beginning with the constituent process, the opposite has occurred. The recent elections reveal that detached and disgruntled voters place little to no faith in the Left’s program and achievements. They continue to perceive that state institutions — schools, health care, infrastructure, law enforcement, etc. — largely continue to fail them.

In a stagnant economy, with job markets as cutthroat as ever, most must still rely solely on themselves and their households amid strained public programs and concerns over the rise of violence nationwide. In the absence of universalist solutions to their basic needs, most working Chileans are now seeking any way to avoid falling further behind. Given the insecurity still gripping most workers, the widespread rejection of the new left’s program in favor of competitive and individualist — and even socially regressive — avenues for meeting their material needs is not only logical, it should have been the expected outcome all along.

Chile’s Shifting Political Terrain

After the major 2022 plebiscite and 2023 tax reform losses, the new left found themselves disoriented. At that point, rather than seeking to rekindle popular expectations and promote strategically coordinated mobilizations, it retreated instead. In the hopes that piecemeal measures might persuade disappointed Chileans that its agenda could still deliver, it chose to turn its formerly tactical 2021 electoral coalition with the center left into a full-fledged governing alliance.

In a cabinet reshuffle just one year after his inauguration, Boric integrated key figures from the old Concertación’s left wing in the hopes that their procedural shrewdness and elite connections would help marshal watered-down reforms. During the 2010s, the social movements that gave rise to Chile’s new radicals (the FA) and revitalized the traditional left (the CP) enjoyed huge successes on the basis of principled critiques of the Concertación’s neoliberal strictures. But after 2022, the new left revived this washed-up political class in the desperate hope that its operators might help achieve small victories within the bounds of neoliberal continuity. However, this gambit only ended up hurting the new left while throwing a lifeline to discredited moderates who re-entrenched their institutional positions.

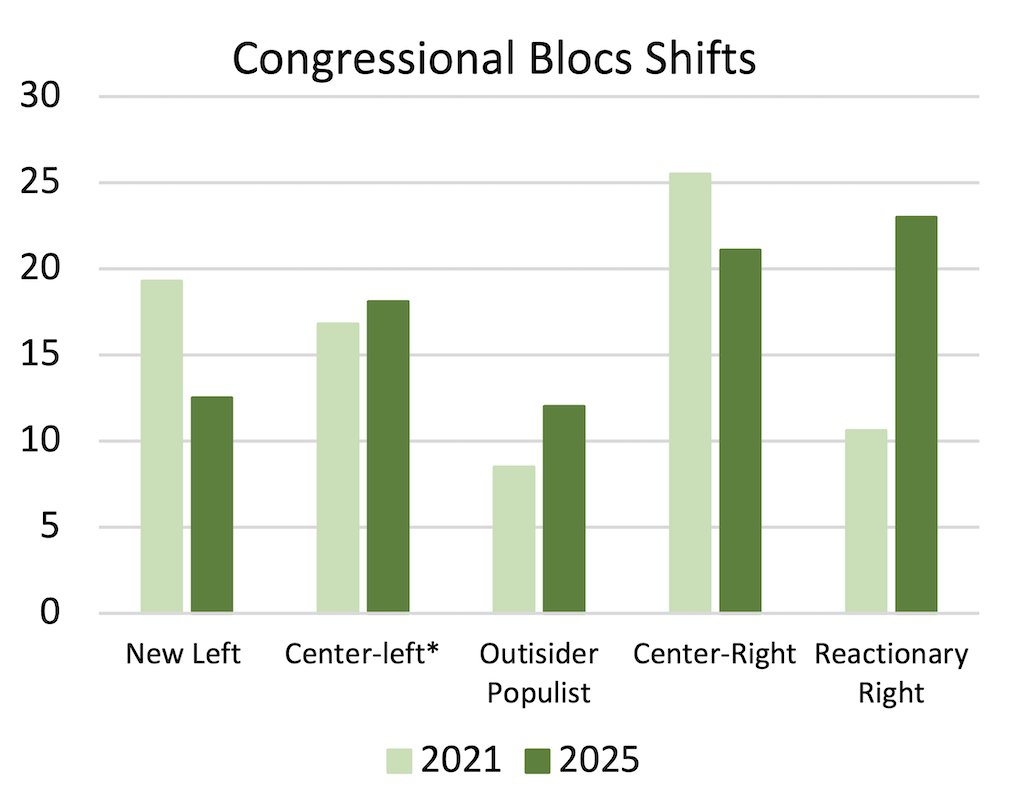

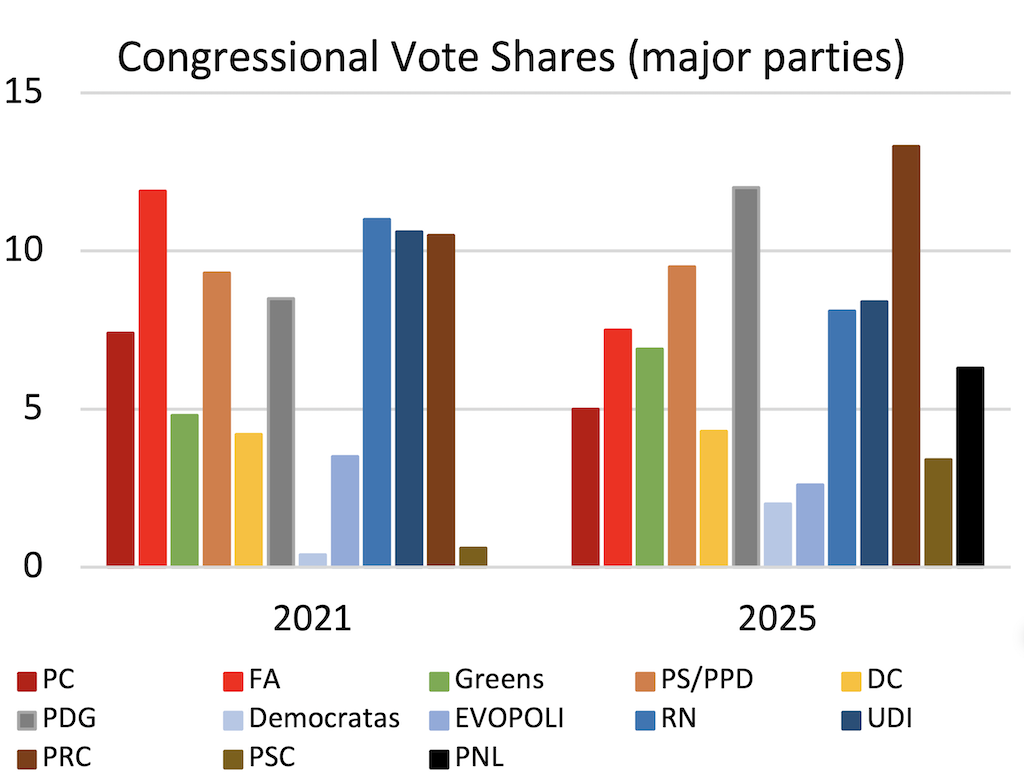

Congressional election results bear this out. While the new-left block dropped by more than a third, from nearly 20 to 12.5 percent, the old center left not only held its votes, it actually enjoyed a slight increase. The FA in particular was penalized. While the CP fell from 7.4 to 5 percent of ballots, Boric’s party sank from the largest party in parliament to sixth place. Meanwhile, the centrist parties that had been headed to extinction stabilized.

At the other end of the political spectrum, the opposite dynamic was at play. The Left’s retreat opened an opportunity for the Right to assert itself, enabling them to subsume the center right in the process. This emerging reactionary bloc now aims to go beyond a restoration of the pre-estallido neoliberal order championed by formerly dominant centrist coalitions. It proposes to push further, returning to dictatorship-era arrangements by sharply reducing public expenditures, eliminating social protections, and abruptly deregulating markets. Kast, for instance, proudly campaigned on US$21 billion in spending cuts. Not to be outdone, Kaiser vowed to scale back corporate taxation by over 25 percent. Both promised to forcibly expel hundreds of thousands of migrants, militarize the border in the north, and send highly armed police into the streets. With their ascendant parties now on the threshold of state power, the far right has positioned itself to immediately install the most repressive, free-market regime since the 1990s.

The reactionaries’ confidence has paid off. Their alliance obtained the highest share of congressional votes, surging to the top from its previous 10 percent. Matthei’s Independent Democratic Union, the least moderate of the old center-right parties, will surely vote alongside the extreme right, lending them another 8.5 percent. If the other center-right parties join in, the right-wing bloc will be a couple of votes shy of a lower chamber majority, all but eliminating the need to negotiate with the opposition. Significantly, the final demise of the thirty-five-year center-right alliance is all but certain. By contrast, Kast’s PR grew most dramatically with seventeen additional seats. Four years after its first elections, it now commands the legislative agenda. The only other party to exhibit such rapid growth is Parisi’s PDG, which added thirteen seats, becoming the second-largest party in Congress.

What the Left Must Learn — and Learn Fast

Not all is lost for Chile’s new left. Despite the near cataclysmic realignment underway, it has not totally crumbled. With a few major course corrections, it just might recover and once again step into power as the political force capable of enacting the reforms desperately needed for the country’s unprotected workers.

For starters, the broad left — including both new radicals and old centrists — is still the largest bloc in parliament. Even after losing eight representatives, it preserved sixty-one seats, nearly twice the number controlled by the far-right coalition. The half-dozen delegates eked out by Christian Democrats, who have always been apprehensive about an alliance with the Communists, will likely jump ship. But the Left should still be able to count on support from at least three progressive independents.

But to regain its influence and efficacy, the new left will have to forge its own path, subordinating the center left much as reactionaries are subduing the center right. Following present losses, the FA-CP partnership still holds seventeen seats. Its congressional presence, however diminished, compares favorably to radicals’ irrelevance during the 1990s and 2000s, when partisan hegemons cast them into the political wilderness. Its delegation can therefore play indispensable roles in recrafting a universalist program of social and economic reforms; communicating it effectively to the majority of Chile’s unprotected workers; and coordinating its policymaking with the mobilization of organized constituents.

Adhering to this type of disciplined strategy — one that places at its center, first, the insecurity afflicting popular sectors and, second, the latter’s collective action — might reinstall the new left as a dynamic pole of attraction. This way, the new left can win back former supporters and begin to incorporate disaffected and atomized workers from among the country’s expanded electorate. This approach would once again punish rather than reward center-left operators who broker deals that defend neoliberal continuity.

Parisi voters, whom both runoff candidates are desperately trying to lure, offer a glimpse into how this strategy might work. The bulk of PDG supporters are, in fact, disenchanted left voters. Most are forty or younger, and three-quarters earn very low incomes. Besides representing the most precarious layers of the working class, many come from the ranks of formerly disengaged nonvoters.

The vast majority of PDG voters eschew clear political orientations, with 70 percent identifying as neither on the Left nor the Right. Yet many also participated actively in the estallido protests when the 2019 rebellion seemed to offer a viable avenue for meaningful reforms. Tellingly, these voters did not throw their lot in with the far right. While they hold strongly anti-immigrant and pro-law-and-order views, they have a general disdain for traditional authoritarian programs. They are also more likely than average Chileans to support reproductive and queer rights and defend state-owned industries. Ultimately, they embrace incoherent but vaguely egalitarian values.

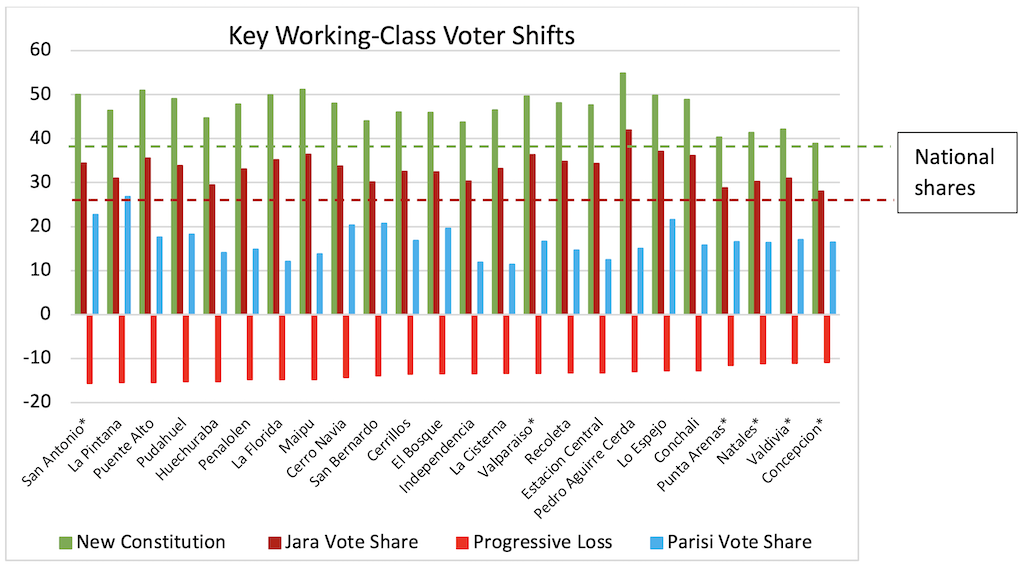

Preliminary evidence suggests that critical sections of Parisi’s backers, after having endorsed the proposed constitution in 2022, simply deserted the Left. The PDG made major inroads precisely in districts where the Left exceeded their national voting averages yet where Jara lost substantial votes relative to progressive support for the new charter. Having concluded that progressive reform failed, hundreds of thousands seem to have migrated over to Parisi’s tent, convinced by his pragmatic offers of a meritocracy that levels the playing field.

These shifts were most pronounced in key working-class districts throughout Chile. Although his support ranked highest in long-neglected northern and southern provinces, the PDG also advanced in the capital’s peripheral townships with the largest working-class concentrations. Parisi similarly expanded his support in central ports, like Valparaíso and San Antonio, where popular identification with radicalism once flourished. San Antonio, a hot spot of recent dockworker militancy, is most illustrative — whereas progressivism lost almost sixteen points there, the PDG expanded its share to 23 percent. These are the workers and communities that the new left can and must win back as it begins its recovery process.

Progressives might wince at the prospects of winning over exasperated PDG voters. After all, Parisi, like Kast and Kaiser, pledged to deregulate markets and deport Venezuelan migrants. Even when defending public industries, his voters are adopting increasingly harsh policy preferences, including a paradoxical hostility to state intervention in the economy. But the new left must quickly grasp that these working-class sectors live and toil in conditions characterized by the absence of effective public institutions and programs.

In the dislocated economies of northern mining towns and in the grinding poverty of Santiago’s townships, they live in a no-man’s-land of unreliable subcontracted work and informal trafficking that breeds chaos and violence. They find Parisi appealing because, having long had to fend for themselves, he’s at least promising public safety and a level playing field. If the new left hopes to recover, its role during the challenging period ahead is to demonstrate to Chile’s workers that socialist reforms can provide more desirable forms of security and equality.