Elites Always Say We Can’t Have Nice Things. They’re Wrong.

All throughout American history, political and economic elites have insisted that better policies — ending child labor, establishing a weekend — were impossible to achieve. They were lying then, and they’re lying now.

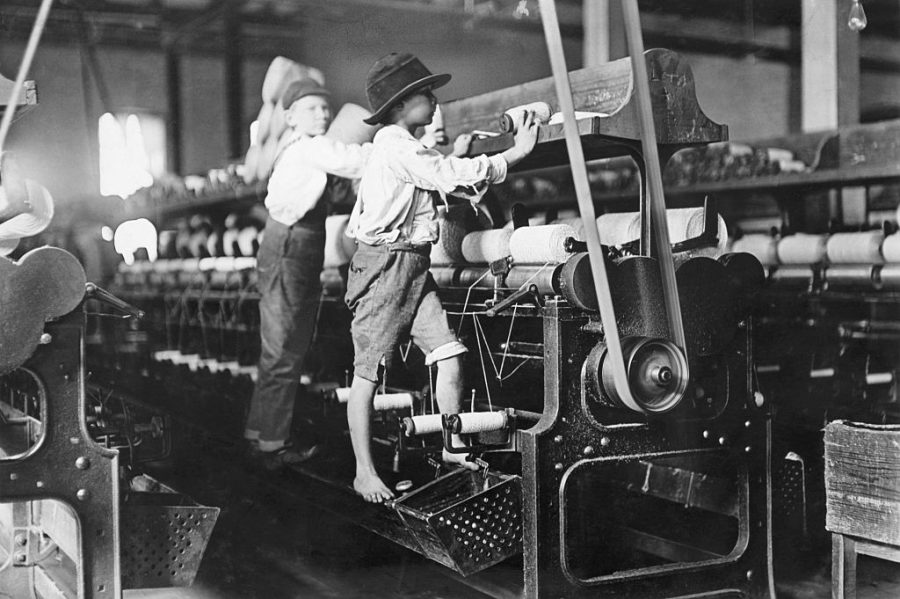

The politicians and capitalists who say we can’t have a rent freeze or universal health care are echoing the words of politicians and capitalists who said we had to maintain child labor and workers couldn’t have a weekend. (FPG / Getty Images)

Day after day, almost all of politics and media is dead set on bludgeoning your brain with one counterintuitive idea: that you can’t make the world a better place, and you shouldn’t even try, because the obvious solutions to people’s miseries would actually just make everything worse.

You hear it all the time. You can’t do a rent freeze, because it will make more people homeless. You can’t pay minimum wage workers more, because it will actually put more people out of work. We can’t move to a four-day workweek, because it will destroy the economy. We can’t have universal health care, because it will make the quality of health care worse.

This is all wrong. But you don’t need to decipher arcane economic models, read scores of academic studies, or even consult a small army of experts to know it’s wrong. You can be sure it is because these apocalyptic predictions are what the forces of greed — big business, right-wing politicians, and the corporate press loyal to both — have always made about any attempt to improve the lives of people who work for a living, going back more than a century.

You may be surprised by some of the measures they fearmongered about, because today they are basic things we take for granted. Things like…

The Weekend

We think of the two days off from work that we enjoy every week as the natural order of things, but it was a hard-fought concession won by workers that is technically not even a hundred years old. Before a five-day workweek officially became federal law with the passage of the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) in 1938, it wasn’t unusual for Americans to work upward of sixty hours a week, with sometimes not even a single day for rest.

Many business owners wanted to keep it that way and argued vociferously against making the five-day workweek the standard.

“The five-day week is impracticable in the steel business and I don’t believe it is practical in any other business,” Elbert H. Gary, cofounder of U.S. Steel, said in 1926, echoing a common talking point used by opponents of the weekend.

If workers were allowed two days off a week, they warned, the results would be “disastrous,” an example of the country “sinking into decay.” The “loss of even a half day when the weather is favorable may result later in the loss of many days, with attendant financial losses, or may even endanger the safety of life or property,” the National Association of Building Trades Employers darkly warned in 1926. It “would be a distinct handicap to the industrial progress of this country,” claimed the president of the N. & G. Taylor Company, echoing frequent employer complaints that it would put US industry at a disadvantage against European competitors.

Big business threw every possible talking point they could at the wall: only some industries could adopt it; it would raise living costs and mean both unemployment and labor shortages; it would encourage “idleness” and maybe even “the loss of inclination to work”; all that extra time “would create a craving for additional luxuries,” warned the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM). And besides, it wasn’t even in the best interests of the workers themselves, a claim that newspapers occasionally found some actual workers to back up.

For all these reasons and more, employers frequently insisted that giving workers two work-free days each week was simply “impossible.”

Employers at the time had plenty of evidence this was nonsense. In 1930, 650,000 workers had a five-day workweek and a majority of the firms that employed them didn’t lower wages or decrease production. A similar majority had reported the same a year earlier, with three-quarters saying they had no gripes with the system. By 1932, two of the country’s largest employers, AT&T and Standard Oil, had adopted it without trouble. Yet even so, as late as 1937, the Illinois Manufacturers’ Association protested that there was “no need” to make it law, and that where it had been adopted had already “seriously contributed to unemployment” in the construction industry, with building having largely stopped “everywhere” because of it.

Working Eight Hours a Day

A similar catastrophe was meant to have played out if workers were prevented from working more than eight hours a day, which likewise became law with the passage of the FLSA in 1938.

It was a “very dangerous experiment” that would be “absolutely unworkable,” according to an association of maritime industry employers in 1918, insisting it would cause “disaster and demoralization of traffic” on the water, “slow up operations over 50 percent,” and create a “coal famine.” Employers wanted to have a peaceful, cooperative relationship with unions, insisted the executive secretary of the National Association of Building Trades Employers, but these were simply “uneconomic demands.”

Such “excessive demands,” charged a representative of the Missouri Pacific Iron Mountain Railroad System, “would work bankruptcy and ruin to the railroad properties throughout the country.” While on the railroads it would mean “industrial disaster,” on farms it would mean starvation. As with the weekend, “impracticable” and “impossible” were the watchwords for opponents of the “exorbitant demand.”

At the same time, many naysayers insisted they were acting in the best interests of the workers themselves. Workers should be allowed to work overtime if they wanted, said one opponent. “If a man wants to work eight hours a day that is his business, but the law has no right to make him work six, eight or ten hours a day,” said Texas gubernatorial candidate Joseph Weldon Bailey in 1920.

But sometimes they didn’t bother to hide their real objections. “Eight hours a day is loafing and giving away the energy that is wrapped up in this country,” objected one manufacturer.

Banning Child Labor

“It is amazing and astounding that it should be necessary to ask Congress to protect childhood,” American Federation of Labor president Samuel Gompers said in 1922, after the Supreme Court struck down a tax meant to penalize the practice. Yet outlawing child labor was a surprisingly heavy lift, opposed for decades on terms similar to these other now commonsense standards, with the FLSA’s ban on child labor extended to the enormous agricultural sector only in 1966 — and even then, the practice continued to slip through the legal cracks afterward.

Banning child labor was likewise declared — what else? — “impractical” by employers who insisted it would simply be impossible to run a profitable business if they couldn’t work kids, often for sixty or more hours a week.

A 1916 House Labor committee hearing on the Keating-Owen Child Labor Act, an early attempt to regulate child labor at the federal level, gives you an idea of how this debate went. One by one, a parade of mill bosses explained that child labor was a “necessity,” and that limiting teenagers to working eight hours a day max would “do the mills great damage,” “turn out of employment a large class of people who need employment,” and would “exaggerate to a much larger extent the hardship” of those already in poverty.

One child labor proponent brought photographs to prove that “the second generation of the cotton mill people in the South are better physically, better looking people, than the first generation,” supposedly proving that the evils of child labor were exaggerated. No one wanted child labor, said another. But how else were poor, often single-parent families going to make ends meet?

In a debate over a 1905 child labor bill in Georgia, which would have banned kids younger than twelve from working in manufacturing, opponents insisted the whole thing was a New England conspiracy to destroy Southern industry. Besides, wasn’t it better for kids without adult supervision to work in factories than to work outside in the sun — or worse, to become criminals and vagabonds addicted to alcohol and cigarettes?

When nothing else worked, defenders of child labor turned to arguments that might sound familiar to us now: attempts to ban it were big government trampling on states’ rights, pushed by radicals and woke activists.

“The power of organized propaganda by minority groups to scare Congress into extreme social regulatory measures has been shown too often in recent years,” complained the Montana State Farm Bureau, a trade association for the agriculture industry, which warned that at “the urge of sentimentalists,” the “federal government is becoming unwieldy with the constant extension of its activities.” Abusive child labor now “exists mostly in the imaginations of well-meaning individuals who accept exaggerated showings” and who are “financed and pushed along by back-stage influences,” charged one newspaper editorial.

“Nothing redder ever came out of Red Russia,” Rev Jones I. J. Corrigon told Congress about a constitutional amendment to ban the practice, which was ultimately approved by both chambers of Congress and ratified by twenty-eight states, warning that it aimed to impose government control over children. It was an attempt “to take away from you the control of the education of your children and give it to a political bureau in Washington,” warned a pamphlet against the measure; “to dictate when and how your children shall be allowed to work” and subject them “to the inspection of a federal agent.”

It all sounds absurd now. But clearly not so absurd to some: child labor is making a comeback in 2025, as dozens of states have introduced or enacted bills to weaken child labor laws in the last few years.

The Minimum Wage

Virtually all of these gloom-and-doom arguments were regurgitated when it came to the minimum wage, another basic standard we take for granted today that was declared “impracticable” and “impossible” by its various opponents.

You can find them all in the June 1937 hearings that Congress held over the FLSA, in which industrialist after industrialist weighed in against its minimum wage provision: it would “increase greatly the cost of production” and therefore prices, eliminating any benefit for workers; cause a chain reaction that would “throw all substandard or marginal workers out of employment as a burden to society” and lead generally to “decreased employment”; lead businesses to turn to “labor-saving machinery” and replace their human workers to save costs; straight up put southern manufacturers out of business; and “make the next depression worse than would otherwise be the case.”

“You cannot legislate a nation into prosperity,” insisted NAM’s Robert Dresser.

But some took it much further. “What is herein stipulated has been tried many times and failed,” lamented the National Publishers’ Association’s Guy L. Harrington. “Rome 2,000 years ago, fell because the government began fixing the prices of services and commodities.” J. D. Battle of the National Coal Association warned that “South Carolina fired on Fort Sumter for far less pretext than this bill affords.”

The hearings were hardly the first time Americans heard this. Similar debates had raged across the country as twenty-seven states and the District of Columbia proceeded to pass their own minimum wage laws between 1911 and 1937, many of them aimed purely at women and girls, who opponents predicted would be thrown out of work if they passed. But neither this nor any of the other predictions of the minimum wage’s foes came to pass in the nine states that had enacted such laws by 1915, federal investigators found that year.

It also wouldn’t be the last time. While they failed to stop the FLSA’s enactment, the minimum wage’s opponents kept on recycling these talking points anyway in the decades that followed to argue against raising it: that hotels and other companies would go out of business, that they would replace people with machines, or that, in the words of libertarian Fox News anchor John Stossel, “we cannot legislate prosperity” — almost word for word lifted from NAM’s seventy-year-old talking points.

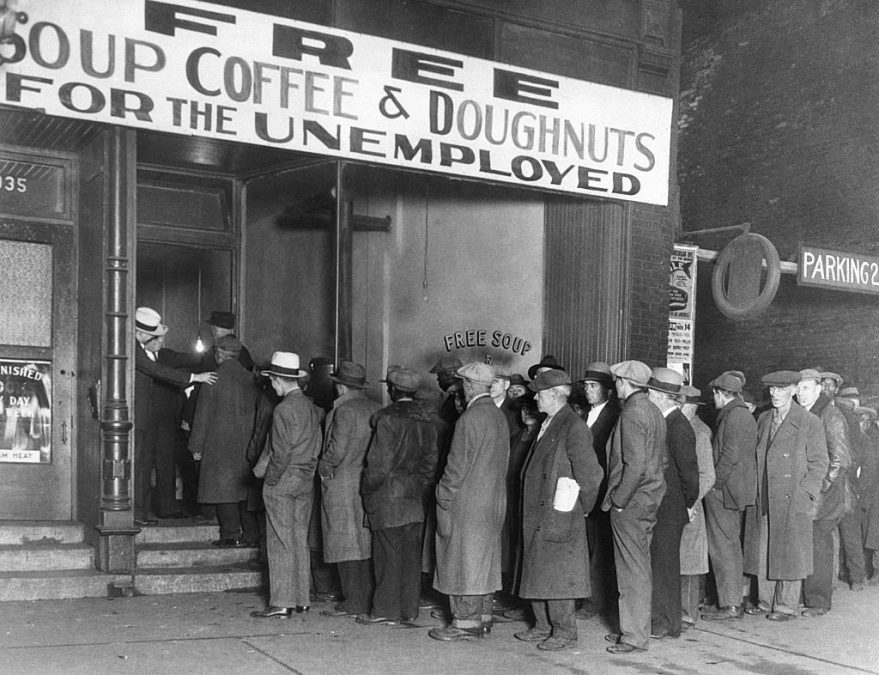

Unemployment Insurance

Unemployment insurance has been a vital lifeline for Americans in times of crisis. After the 2008 financial crash, it helped support nearly sixty-nine million people, roughly a quarter of them children. More recently, its expanded version during the pandemic kept millions of Americans out of poverty while the economy was shot.

Nevertheless, it was bitterly opposed when it was first proposed on the grounds that — well, you can probably guess by now.

As early as 1924, for instance, the Detroit Free Press declared the idea, as it picked up momentum at the state level, “economically unsound and impractical,” and that its use in Europe showed that it would simply become a “premium on idleness.” Eight years later, NAM’s then president lamented that while the organization was deeply sympathetic to workers’ demands for unemployment insurance, “it would be difficult, if not impossible, to keep such a plan actuarially sound and solvent.”

As it advanced at the federal level, the Wall Street Journal’s Bernard Kilgore — who would become the paper’s managing editor and, later, president and chair of Dow Jones & Company — produced a lengthy column laying out why an unemployment insurance system simply couldn’t work in practice. It was impossible, he claimed, for nation states to save or invest their reserves as ordinary people can, he wrote, so unemployment insurance was bound to “produce nothing but disappointment and disillusionment.” (In reality, it has worked for decades by state governments building up reserves in trust fund accounts with the US Treasury that are supplemented by other federal trust funds, and the policy’s biggest problem is underfunding by Congress.)

The idea’s suspicious Europeanness was a common theme. The country should reject the idea and “reassert the sturdy, self-reliant, independent American individualism that has ever been this nation’s proud birthright,” urged Rome C. Stephenson, president of the American Bankers Association. Merwin K. Hart, president of the New York State Economic Council claimed that in England and Germany, the scheme had turned “the minority of shiftless and improvident persons” into a “burden that the great majority of honest and industrious persons had to carry.”

“We in America have other ways of doing things. We are greater industrialists,” he concluded.

He, like other opponents, resorted to the same kinds of sky-is-falling catastrophizing that you should be familiar with by now. At a March 1934 Congressional hearing on unemployment insurance, opponents pulled them out one after another: it was an impossible burden on employers, it would lead to mass closures and layoffs, and workers would be replaced en masse by machines. One industrialist pointed to the Wagner Act that was winding its way through Congress at the same time, and which would create the National Labor Relations Board, complaining that “you keep on piling these things upon industry.”

Wrong Then, Wrong Now

Nearly a century on, it takes the average person roughly a second to call bullsh-t on all of these arguments, and to recognize they’re not just wrong, but laughably wrong.

Giving workers the weekend off didn’t destroy or handicap the US economy, nor did it kill housing construction. Letting them work a maximum of eight hours a day didn’t bankrupt the railroads or end the American work ethic. Outlawing child labor didn’t lead to a dictatorship. The minimum wage didn’t lead to mass unemployment or the collapse of the United States. Unemployment insurance is today considered as American as apple pie.

Not long after these measures were enacted, in fact, the United States became a global superpower, and Americans enjoyed what we now look back on as a period of unmatched prosperity. All of it was possible. All of it is now basic common sense. Imagine what else will be, too.