1960: The Year the Modern Horror Film Was Born

A combination of the breakdown of the Hollywood studio system, the decline of censorship, and the rise of wildly — and luridly — creative filmmakers across the world looking to cash in on sex and violence made 1960 the year of the modern horror film.

Still from Peeping Tom. (Anglo-Amalgamated Film Distributors)

For horror film aficionados, the year 1960 will always be associated with Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, which is generally argued to be the first “modern” horror film. The year is even more of a landmark if you consider that Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom — featuring many of the same traits as Psycho, including a sympathetic portrait of a sexually tormented serial killer who is not a reassuringly “othered” monster — debuted only five months before.

The two British directors knew each other, and Hitchcock was paying close attention to the grim fate of Powell, whose masterpiece so repulsed British critics and the public that his career never recovered. In a strategy designed to control the reception in America, Hitchcock oversaw a famous publicity campaign for Psycho intended to prepare his vast audience for a transgressive new experience. A major part of the strategy was defusing audience revulsion, using the celebrated director’s well-known black humor that had helped make his television anthology series Alfred Hitchcock Presents such a big hit. In a preview short film that circulated widely before the premiere of Psycho, Hitchcock himself toured viewers through the Bates Motel and the gothic Bates residence behind it, reacting with comically exaggerated distaste at the lurid violence, supposedly too horrible to fully describe, that would take place within.

Hitchcock also took obviously gleeful pleasure in showing audiences the first shot of a toilet flushing in an American film — the commode in Room #1 at the Bates Motel. It was a humorous indication of the crumbling of the strict Production Code of censorship that had dominated American movies since it was first enforced in 1934.

There had been a slow erosion of Code enforcement since the mid-1940s, when the harsh experience of the war gave rise to new energy in documentary filmmaking and realism in motion pictures. The surge in documentary filmmaking was powered by technological advances such as faster film stocks and more portable cameras and sound equipment as well as increased audience investment in seeing what was really happening on war fronts across the globe.

Realist film movements followed the war, most famously Italian neorealism breaking the constraints of fascist censorship, which had confined popular movie-making to the glossy fantasies generated within the bounds of studio production. Just the act of neorealist directors taking their cameras out into the streets was informed by radical leftist rejection of escapist film forms.

In Hollywood, the rising demand for realism led to the same tendency to break out of studio sets and back lots in favor of on-location filmmaking. This inevitably led to more adult content. The crime film genre that came to be known as “film noir,” noted for its extreme violence, lurid sexuality, and existentially grim view of the world, emerged in full force only after the war. The genre had been catalyzed by the hard-boiled novels that had been popular since the 1920s, but any film adaptations were suppressed by the Code in the 1930s and further stifled by the war effort in the early 1940s, which mandated cheerful and patriotic representations of American life.

The End of Hollywood Censorship

In addition to the new dedication to realism was the breakdown of the Hollywood studio system, as the desire for new modes of entertainment emerged after the war along with changing movie-going patterns driven by a mass exodus of middle-class Americans to the suburbs. While art cinemas featuring “foreign films” proliferated in startling numbers in urban areas and university towns across America, the popularity of television exploded. It quickly took over as America’s main source of family entertainment, and as such, became the most highly censored form. In order to hold some portion of the general public, movies skewed toward widescreen Technicolor spectacles or more serious, often daringly topical black-and-white adult fare — extremes beyond what could be shown on early television.

Directors began systematically testing the limits of censorship. Otto Preminger led the charge by making an innocuous romantic comedy, The Moon Is Blue (1953), that featured the use of formerly forbidden words like “virgin” and “pregnant.” He followed it up with a noirish drama on the taboo subject of drug addiction, The Man with the Golden Arm (1955).

Both films were released without the Production Code of America seal of approval, which once upon a time would’ve barred the films from the major theater chains, dooming them to marginal independent cinemas and probable financial failure. However, independent theater chains had expanded in the wake of the Paramount Decision, a landmark ruling against the major theater-owning studios for their oligopolistic business practices. The 1938 ruling was finally enforced in 1948 and became one of several post–World War II blows to the studio system that ultimately dismantled it.

The two Preminger films, released with “adults only” warnings, made them notorious as well as very popular. The process of chipping away at Production Code restrictions gained momentum, though it took until 1968 for its entire dismantling and replacement by an early version of the motion picture content ratings system we still have today.

As formerly censored topics in films became appealing, a whole new strain of “social problem” films arose starting in the late 1940s. These films dealt with such subjects as physical and mental war trauma (Pride of the Marines, The Best Years of Our Lives), mental illness (The Snake Pit, The Three Faces of Eve, Home Before Dark), alcoholism (The Lost Weekend; Come Back, Little Sheba), antisemitism (Crossfire, Gentleman’s Agreement), racism (Intruder in the Dust, Pinky, Border Incident, Home of the Brave, The Defiant Ones), rape (Outrage), and unwanted pregnancy (Not Wanted).

Horror Goes Global in 1960

For horror films in particular, this atmosphere eventually led to a burst of dark creativity, culminating in the banner year of 1960. But this surge was a truly international phenomenon that went beyond the UK’s Peeping Tom (premiering April 7) and America’s Psycho (September 8). Eyes Without a Face, a French horror masterpiece directed by Georges Franju, premiered on March 2 and is regarded among the first films of the highly influential youth-cinema movement, the French New Wave, that had riveted the cinephile world with Francois Truffaut’s The 400 Blows and Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless the year before.

Eyes Without a Face is a unique film about an arrogant scientist (Pierre Brasseur) whose daughter’s face has been horribly damaged in a car accident he himself caused. He preys ruthlessly on young working-class women who are abducted by his blindly devoted assistant (Alida Valli) for the purpose of finding a new face to graft onto that of his suffering daughter, Christiane (Edith Scob). One scene depicting the surgical removal of a young woman’s face, which would surely have been censored in earlier years, still holds up today as a remarkable combination of delicacy and gruesomeness that defines the entire film. And the most unforgettable scenes involve the eerie, doll-like quality of the captive Christiane, thin and ethereal in a white mask and white satin robe, as she drifts through the doctor’s ghastly laboratory as well as the outbuilding housing the doomed, yelping stray dogs he also experiments on.

The two modes of Eyes Without a Face — appalling modern-day realism in depicting psychological sickness, harrowing cruelty, and shocking gore, and newly inventive gothic effects that harken back to the classic horror being left behind — comprise the major developments in cinema in that reach an inspired peak in 1960.

In Italy, horror director Mario Bava made his 1960 debut with Black Sunday (August 11), a period horror film about Satanic possession and a witch’s revenge that made Barbara Steele, in a dual role, a star and instant horror icon. The first scenes of Black Sunday, which depict the realistic branding of the condemned witch and her grisly death via an iron mask that impales her face with spikes, play like a declaration of new levels of sadistic violence and bloodshed. Bava went on to experiment in giallo and slasher horror films in ways that inspired the other two masters of Italian horror, Dario Argento and Lucio Fulci.

But Bava himself had been inspired by the rise of England’s luridly violent but elegantly shot Hammer Horror films of the late 1950s. These movies shocked audiences around the world with their reconceived versions of gothic classics like Dracula, Frankenstein, and The Mummy that had once been the province of Universal Studios in Hollywood. Hammer’s The Curse of Frankenstein (1957), directed by Terence Fisher and starring Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee, was such a popular smash it was quickly followed by sensational remakes of Dracula and The Mummy with the same team of director plus lead actors, all in thrilling color with plenty of charged sexuality and lurid gore. The 1960 Dracula sequel, Fisher’s The Brides of Dracula, premiering on July 7, is a less remarkable or historically significant film on its own, but it continued the recent Hammer string of influential moneymakers, featuring Cushing reprising his role as Van Helsing, but doing without Lee as Dracula because the actor feared typecasting.

In America, the same move toward classic gothic horror reconceived in terms of color filmmaking and greater explicitness found a home at American International Pictures (AIP). Taking a chance on a bigger budget in adapting Edgar Allan Poe’s celebrated short story “The Fall of the House of Usher,” AIP was rewarded with a 1960 hit film House of Usher, which premiered on June 18. It was directed by Roger Corman and starred Vincent Price as the morbidly tormented last heir of an aristocratic family line who may or may not have buried his beloved sister alive in the family tomb. Its popularity guaranteed a long series of AIP Poe adaptations, directed by Corman and starring Price along with a host of aging Hollywood actors all of whom somehow associated with horror, including Peter Lorre, Boris Karloff, Basil Rathbone, Ray Milland, and Lon Chaney Jr.

The countervailing tendency in AIP horror was making cheap exploitative movies shot in black and white, featuring largely unknown actors, and ground out fast, including the farcical Little Shop of Horrors. Directed by Corman, it’s still the most famous and influential of them all, though it was largely overlooked in its initial release on September 14, 1960.

It occupied the second half of a double bill featuring Bava’s well-reviewed hit Black Sunday, which was distributed in America by AIP. Over time, Little Shop of Horrors gained a cult following as the drunkenly scripted, cheerfully bizarre tale of a man-eating plant from outer space who’s fed by a hapless and desperate working-class struggler. It also features a young Jack Nicholson in an early role as an enthusiastic masochist looking forward to his painful session at the dentist’s. The film’s lighthearted subversiveness played well over the years on television and inspired a hit Broadway musical comedy in 1982 that was followed by a popular 1986 movie adaptation starring Rick Moranis and Steve Martin.

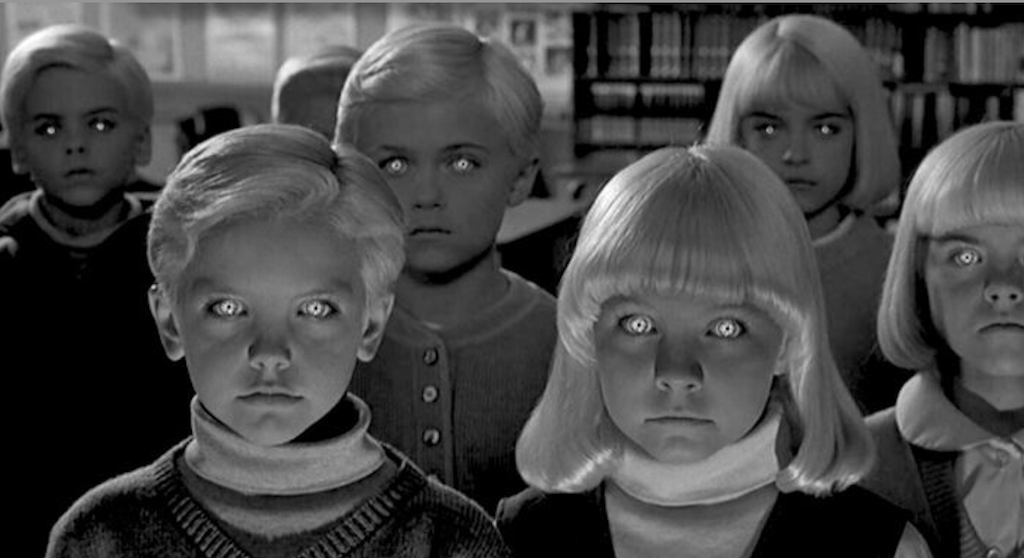

In an era of international coproductions bolstering filmmaking budget costs as the studio systems in many countries were falling apart, there were a number of US-UK horror films made in the early 1960s. Village of the Damned, premiering in the United States on December 7, had many of the qualities of other highly praised US-UK horror films at the time, including The Innocents (1961), The Haunting (1963), and The Nanny (1965), as well as the sequel Children of the Damned (1964). They combined sleek, elegant shooting styles and the restrained tone of atmospheric gothic chillers with sensationalistic, formerly censorable narrative elements at the center of the horror.

The Haunting, for example, is set in a classically haunted gothic-style old house in a film designed by director Robert Wise to pay tribute to his forward-thinking mentor Val Lewton, who made quietly ambiguous 1940s horror films such as Cat People, I Walked with a Zombie, and The Leopard Man. Lewton’s films were described as achieving psychologically ambiguous “fear-by-suggestion” among mostly modern-day characters rather than classic “monster movie” shocks and thrills. The Haunting also features a modern scientist’s evidence-based approach to studying paranormal phenomenon, and a chic lesbian character — among the first in mainstream cinema — offering an attractive alternative to the protagonist, a lonely, psychologically troubled single woman who’s losing herself to either mental illness or ghostly possession or both.

The Family and Modern Horror

Central to the narratives of The Innocents, Village of the Damned, and Children of the Damned are the idea of children represented as the monstrous beings within tormented households. These characters once would’ve been censored under vague terms in the Production Code involving reverence for the family and the investment in ideals of youthful innocence and wholesomeness.

The waspish actor George Sanders, complete with ascot, plays the lead in Village of the Damned, as scientist Gordon Zellaby, living in rural Midwich, England, a village that experiences an alarming event when everyone simultaneously loses consciousness for a full day. This event is treated by the government and military as a Cold War phenomenon, possibly involving an attack by the Soviets, until it’s discovered that towns around the globe, including two in Russia, suffered a similar fate. The local government representative puts Zellaby in charge of monitoring the mysterious phenomenon that follows: shockingly, every single fertile woman in Midwich is pregnant, including Gordon’s wife, Anthea.

Six months after the attack, all the babies develop at superhuman rates of growth — identical white-blonde hair, strange pale eyes, and hyperintelligence that includes ESP. Soon it’s impossible to avoid the realization that the children must be alien spawn preparing themselves to control the world, and their violent laser-eyed killings of those who think about impeding them in any way becomes the problem for a terrorized village, and more specifically for Zellaby. How to destroy their own half-alien children without the children knowing what the villagers are planning?

That might sound to you like the famous Twilight Zone episode “It’s a Good Life,” about a town held captive by a malevolent, supernaturally gifted boy who can read minds and, with a single murderous thought, send people who offend him “to the cornfield.” Television horror series of the 1950s and ’60s, such as Alfred Hitchcock Presents, Twilight Zone, and Outer Limits were also in a remarkably inventive era. “It’s a Good Life” ran on November 3, 1961, but was based on a 1953 short story of the same name. It’s illustrative of one aspect of the cultural fallout of World War II, which included a notable preoccupation with “bad children” and juvenile delinquency. The films Youth Runs Wild (1944), Bad Boy (1949), So Young, So Bad (1950), The Wild One (1953), Rebel Without a Cause (1955), Blackboard Jungle (1955), The Bad Seed (1956), Reform School Girl (1957), High School Confidential (1958), This Rebel Breed (1960), and The Young Savages (1961) are examples of the trend.

Gothic Spooky Old Houses Meets Modern Horror’s Savage Killers

The tension of reconceived gothic horror and realistic modern horror combined became explicit in Psycho and Peeping Tom, both featuring plaintively shy, lonely, reclusive young men whose psychotic homicidal urges emerge out of their childhood homes, the gothic “old dark houses” where both still live.

The gothic Bates residence, reflecting the holdover of repressive, controlling Victorian values held by the late mother of Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins), is still the most famous building on the Universal Studios tour. It looms dark and grim behind the flat, modern utilitarianism of the one-story Bates Motel where Norman’s voyeuristic spying on women ignites murderous frenzies from the “mother side” of his split personality.

Peeping Tom features a different configuration within the home of photographer/cameraman/lethal voyeur Mark Lewis (Carl Boehm), whose late father (played by director Michael Powell himself) was a domineering scientist studying “fear reactions in children” by training a camera on his own child through a lifetime of sadistic experiments. Instead of a motel allowing some slight public access, Mark rents out most of the rooms of his father’s house, keeping only a small living space for himself that contains his father’s books — case studies based, in part, on his traumatic childhood. There’s a sinister darkroom and screening room curtained off behind it devoted to photography and film. There Mark screens snuff films of his own creation, the footage he shot of women being murdered with his own camera fixed upon a tripod with a knife attached to one of its legs.

By 1968, the way realistic modern horror had been paired with and begun to replace gothic horror was so obvious it went from subtext to text and becomes the plot of the film Targets, Peter Bogdanovich’s feature film debut produced by Corman. In it, Boris Karloff plays a character based on himself, an elderly horror movie icon named Byron Orlok, who knows his brand of gothic horror has become quaint, outmoded, and ineffective in a world where real-life horrors overwhelm it.

Representing contemporary horror is a serial killer named Bobby Thompson (Tim O’Kelly), a seemingly well-adjusted all-American guy, who snaps, kills his family, and goes on a deadly, apparently unmotivated shooting spree. He winds up at the drive-in where the last Byron Orlok film is playing, shooting through the screen — with its gothic imagery flickering — at the audience in their cars outside. The Bobby Thompson character was based on the real-life mass shooter Charles Whitman, a clean-cut ex-Marine who suddenly murdered his wife and mother and then shot seventeen strangers on the campus of University of Texas at Austin, some from the clocktower, which made him notorious as the “Texas Tower Sniper.”

Whitman famously left a note pondering his own psychopathology, which he professed not to understand. He asked for any money left over from paying his debts to be donated to a mental health foundation that might do research on the source of his “unusual and irrational thoughts,” discovering their cause and treatment, which might “prevent further tragedies of this type.” His plaintive seeking of self-understanding is hauntingly similar to that of the lead characters of both Psycho and Peeping Tom. Norman Bates speaks guardedly but yearningly with Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) about his own psychologically driven state of entrapment in the scene before he kills her — and Peeping Tom, as Mark Lewis seeks the advice of a psychiatrist about how “a friend” suffering from psychotic compulsions might be analyzed and cured.

The groundwork for contemporary subgenres such as serial killer movies and TV series, slasher horror, and torture porn can all be traced back to the shifts that occurred in 1960. But beyond tracing the path of influential films, it’s worth attending to these extraordinarily propulsive years of creativity in film, like 1960. Taking such a focused look at one surging genre in one landmark year allows you to interrogate the cultural tendencies producing both a rapid breakdown of older forms and systems, and the exhilarating growth of new ones, all of which are informing a sudden effusion of creativity.

And it makes you wish to be able to interrogate the present year with anything like the same clarity. In sixty-five more years, if we’re still here, will critics look back and perceive 2025 as a landmark year in terms of film and media in any way beyond charting systems in messy decline? I hope so.