The Left Needs Utopian Thinking

Conservative apologists for the status quo often stigmatize their opponents as “utopian.” But socialists and feminists shouldn’t be afraid of the term, since utopian thought can play an important role in helping us develop practical alternatives.

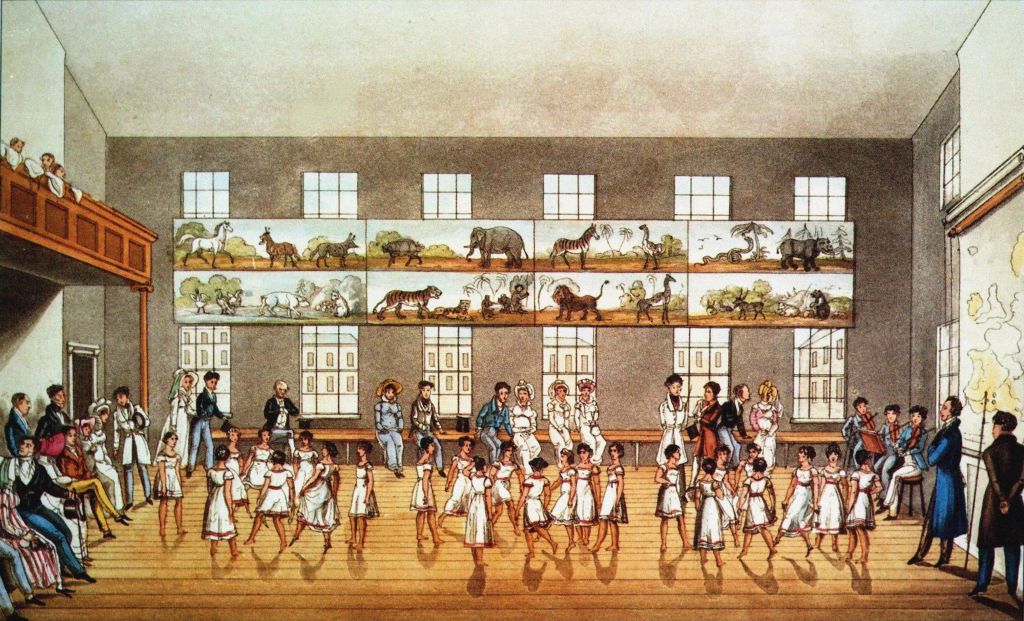

Depiction of a dancing lesson at Robert Owen’s Foundation New Lanark, 1823. Private collection, artist anonymous. (Fine Art Images / Heritage Images via Getty Images)

“Under no system of social arrangements founded on individual competition for individual wealth can women enjoy equal happiness with men.” Thus Irish socialists William Thompson and Anna Wheeler linked gender-based and economic oppression in their book-length feminist retort to James Mill, published in 1825. Such arguments would become fundamental, even obvious, to latter-day Marxists.

Yet Karl Marx himself criticized the movement from which Thompson and Wheeler emerged. They were followers of Robert Owen, one of the nineteenth-century “utopian socialists” that Marx and Friedrich Engels discussed in the Communist Manifesto. According to the Manifesto, figures like Owen produced “fantastic pictures of future society” that lacked a grounding in real class struggle.

As Barbara Taylor showed in her classic history Eve and the New Jerusalem, Marx and Engels’s assessment was unfair to the Owenites, whose thinking on vital questions like the emancipation of women placed them surprisingly close to the more compelling among today’s feminist views, compared with the Owenites’ progressive contemporaries and even later socialist movements. More generally, the argument for the superiority of “scientific” over “utopian” socialism, to use the terminology of Engels, depends on questionable premises and ultimately obscures the value of utopian thought for the project of social transformation.

What’s Wrong With Utopia?

To understand anti-utopianism, it helps to identify two kinds of arguments. David Leopold, a scholar of Marx and utopia, provides a useful distinction between foundational and nonfoundational objections. Foundational objections reject all detailed descriptions of ideal but nonexistent societies (to borrow Leopold’s definition of utopia), whereas nonfoundational objections oppose particular features of particular examples of utopian thought. As Leopold demonstrates, Marx and Engels criticize utopian socialism in both of these ways.

Perhaps the most glaring problem with utopianism is its associated theory of change. As Marx and Engels argued, the central strategy of Owenism, which involved operating through the force of example and moral persuasion, required those who were already in power to be won over. Unless the movement had a theory of how the oppressed majority might seize power, it needed to persuade a critical mass of those who held the material resources under capitalism in order to build the social institutions it proposed.

But Owen’s fellow industrialists had little incentive to build utopia, since the existing system gave them a level of wealth and status that a truly egalitarian transformation would deny them, while workers had more to gain. A theory that grants a more central role to material interests and class struggle is thus preferable, though moral persuasion should still play an important part (in producing “class traitors” such as Marx and Engels, as well as in convincing workers).

In Leopold’s terminology, this objection to utopian thought is compelling but nonfoundational. Nothing about utopianism as such requires a theory of change that focuses on moral persuasion while ignoring class struggle. To see the value in drawing up a detailed socialist blueprint, we need not believe that the sheer rationality of the blueprint will bring about its widespread realization as a social system.

Leopold identifies three foundational criticisms that Marx and Engels level against utopianism as such. The “normative claim” is that utopianism is undemocratic: people in the future society should collectively decide how they will live, and we should not presume to do it for them in advance. The “epistemological claim” is that utopia is unknowable: we simply can’t form an accurate picture of the good society from our current vantage point (and only a fully accurate picture would be useful). The “empirical claim” is that utopian construction is unnecessary: historical materialist analysis demonstrates the inevitability of a revolution that will replace capitalism with communism.

Such objections have had a long afterlife. Though few still think that successful revolution is inevitable, having seen capitalism adapt to survive many crises, variations on the epistemological and empirical objections continue to haunt political and theoretical discussions. Even defenses of utopian thinking tend to extoll the merits of fragmentary and vague visions of the good society. Indeed, some writers affirm such fragmentariness and ambiguity as features of distinctively feminist utopianism.

I agree with Leopold that the foundational objections fail. Against the epistemological argument, Leopold convincingly argues that even imperfect goals serve as useful guiding principles. It is through making plans and attempting to carry them out that we exercise our constructive agency, collectively as much as individually. While we can never know all the relevant circumstances to perfect our plans, fallible goal-setting exercises are nevertheless valuable.

As for the normative concern, surely the people whose autonomy a theorist might want to protect can decide for themselves whether they want to endorse that theorist’s views about the good society and can amend it as needed. Indeed, authors who hesitate to specify desired outcomes for fear of foreclosing debates or future possibilities risk a different kind of undemocratic elitism: they exaggerate their own intellectual authority. Leopold rightly points out that the “mere existence” of plans for a future society doesn’t limit the autonomy of the individuals who set out to transform society.

Of course, the antidemocratic force that stands behind utopian blueprints can sometimes be of a more material nature. Robert Owen himself exerted such force, leading to the failure of the community his followers established at Queenwood. When the largely working-class, collectively governed community was struggling financially, Owen and a group of bourgeois reformers — known as the “Home Colonisation Society” — demanded control of its governance in return for funding.

As Barbara Taylor recounts, Owen spent “thousands of pounds building sunken walk-ways, promenades, and the famous kitchen, thereby exhausting all the movement’s central funds.” The community eventually mutinied and gained back democratic control over its affairs. Ultimately Queenwood failed to resuscitate its finances and dissolved in 1845. The broader Owenite movement soon followed suit.

But this example raises a nonfoundational objection. The experience of Queenwood should warn us not against utopia but against the domination of utopian visions by individual founders. It was not any fact about utopian thinking as such but rather Owen’s fairly banal power grab that pitted his project against democracy.

Recovering Owenite Radicalism

If Owenism was thus no paragon, the movement still deserves more credit than Marx and Engels gave it. While the founders of Marxism respected the social critique that the first generation of utopian socialists put forward, agreeing with their opposition to patriarchal family structures, the wage system, and industry conducted for private gain, they dismissed the constructive proposals of the utopians for replacing these institutions as fantastical. As history progressed and the possibilities of class struggle unfolded, Marx and Engels concluded, utopian socialism lost its radical bite:

Although the originators of these systems were, in many respects, revolutionary, their disciples have, in every case, formed mere reactionary sects. They hold fast by the original views of their masters, in opposition to the progressive historical development of the proletariat.

There may be some truth in this observation, but certainly not “in every case.” As Taylor shows, Owen’s predominantly working-class following went beyond his own views, both in terms of radicalism and in embracing strategies closer to those Marx advocated, as evidenced by Owenite labor militancy in the 1820s and ’30s.

Notably, Owenite feminism was distinctively radical. Owen and his followers championed the equality of the sexes (if sometimes more in theory than in practice). They condemned the antisocial tendencies fostered in a system of atomized families each striving for its own gain and proposed communal child-rearing as a way to educate unselfish, community-minded members of society. While Owen’s proposals initially failed to challenge women’s work as a category, Thompson and Wheeler introduced into Owenite thought the idea that a gendered division of labor prevented women’s equality.

Owenism provided a framework and platform for the political involvement of working-class women. While men dominated the higher echelons of Owenite organization, women participated extensively. Taylor describes how they engaged in militant labor activism, delivered popular lectures, and prefigured egalitarian relations by dining at mixed tables, a practice that sparked controversy in the face of Victorian gender norms.

Along with private property and religion, Owen condemned marriage, proposing free unions of affection instead. Among his followers, disagreement arose about sexual freedom, and debates raged over whether (in the language of the movement) abandoning marriage was already appropriate in the “Old Immoral World,” or only the “New Moral” one. As Taylor observes:

Under the pressure of this dissent, the Owenite “line” on marriage, which had originally been represented only by Owen’s Lectures, began to dissolve into a range of positions, veering between various re-workings of his libertarian philosophy and a belated recognition of the vulnerability of women, particularly unmarried women.

Owen’s followers thus represented a working-class movement with a feminist consciousness. Through lively discourse and dissent, they adapted his ideas to their own realities and discontents. Though Owen propounded equality, including between the sexes, he failed to emphasize the agency of the working class in fighting its own oppression, something that was put into practice by the political activity of working-class women in the movement.

Those of us who rely on Marxist ideas for social critique might nevertheless resist the urge to appeal to Marx where utopia is concerned. We can follow Marx and Engels in rejecting Owen’s ideas about change and leadership, and we can condemn Owen’s own antidemocratic tendencies, while still reaping the benefits of utopian thinking — including the bits that the Owenites got right.

What Use Is Utopia?

If we acknowledge that Marx and Engels were unfair to the Owenites in particular and to utopians in general, we still face the question of what, if anything, utopian thinking can offer us today.

First, as Mark Fisher pointed out, succumbing to a sense of doom reinforces the status quo. A detailed vision of a bright future can have denaturalizing, uplifting, and mobilizing effects, helping to shake the sense that things can only be as they are (or worse) and to motivate people to collective action. Second, the Right is already doing a good job of painting pictures of alternatives; the Left needs to compete.

A third answer is that we need utopias for feminism. Some even claim that feminism itself is necessarily utopian. In her 1982 article on feminist utopian fiction, Anne Mellor, for instance, called feminist theory “inherently utopian” because “equality between the sexes” had “never existed in the historical past.” If the goal of feminism has not been achieved even according to this fairly narrow 1980s definition, then commitments to emancipation from oppression on the basis of sexuality, gender nonconformity, and transness must render feminism necessarily all the more utopian today.

This is simultaneously a right and a wrong way to look at the question. It is certainly true that the proper aims of feminism have nowhere been realized — not in the Owenite communes that professed equality but still tended to assign the cleaning, cooking, and childcare to women, and not in the ancient matriarchies whose myths 1970s radical feminists sought to write into history. Unquestionably feminism needs utopia because it needs to look to the future for answers.

But this is true not merely in a definitional sense, whereby all that is feminist is already utopian. Instead feminism needs utopia not as a vague orientation toward the future but as a reflective method: to formulate properly feminist aims, we cannot look only to the past or to contradictions in the present — we have to work out what future society we want, and what would make it plausible and desirable.

The commitment shared by Marxists and Owenites to connecting feminist questions with broad social transformation is key. Any good socialist feminist knows that true feminism is incompatible with capitalism. One reason is that women’s liberation involves socializing reproductive labor in ways that can’t be done under capitalism (or at least not in a way where the cure wouldn’t be worse than the disease).

Comparing utopian thought to a one-dimensional Marxist understanding of revolution helps clarify its distinctive usefulness. We have no good reason to think that the transformation of one element of society — through seizure of the means of production by the proletariat, for instance — will inevitably, and without the need for advance design, lead to the desirable transformation of all the other elements.

Utopian thinking can help us imagine a social world to aim for by considering which desirable elements might reinforce one another, which institutions are preconditions for the existence or stability of others, and how we can make coercion obsolete to the fullest extent possible. It is especially valuable, then, to envision in detail an ideal society, from its economic, political, and reproductive institutions to the texture of the psychological experiences and personal relationships it fosters.

The ambivalence about marriage among Owenite women and their female audiences that Taylor identifies may seem like a point against utopia, since rigid blueprints foreclose such contestation. But there is a different and better way to understand the constructive aspect of utopia. Utopianism as a mode of political thought allows radical political theorists and movements to consider and contest what set of institutions and practices they would like to build in place of those to be abolished, and to consider each of these in the context of a social whole.

For example, while abandoning marriage in the nineteenth century might have hurt women by reducing men’s material responsibility for children, a world without the marriage contract would nevertheless be a better one, opening up possibilities not only for women but also for queer people. A precondition for this better world is the socialization of childcare and the abolition of private property, which Owen and many of his followers also advocated, since those changes would obviate the need for assigning financial responsibility to fathers.

Still, isn’t Marx right that a goal that seems radical today might be reactionary in a few years or decades? And how do we know whose utopia to pursue? In a recent paper, the political theorist Titus Stahl follows Leopold in rejecting the foundational objections to utopian design. But Stahl subscribes to a weaker caveat: since the very concepts we use to understand the world and formulate our aims have been formed within the unjust social structures we inhabit, we can’t use them to come up with the ideal society right now.

However, utopian visions needn’t emerge fully formed from one person’s mind. As the Owenite movement shows, even with a leader who tries to entrench his own designs, the utopian vision at the movement’s core can nevertheless explode into variety and disagreement without becoming any less utopian. Collective revision of utopian goals through democratic contestation can square the circle.

Stahl argues that utopia should not be a static end point but a target for us to continually debate and reconceive as experiments yield results and circumstances change. He also contends that we can evaluate utopian proposals based on the success with which they would resolve the problems plaguing existing society. To invent and assess utopian visions in this way requires no impossible leap away from our historical standpoint. Of course, practice is the ultimate test, but we can use theory to make predictions and choose among utopian goals based on those predictions.

Brighter Futures

Taylor’s book offers a somewhat melancholy coda to illustrate the lost radical potential of Owenite feminism. She draws a comparison with Chartism, a contemporary movement that sought to address the concerns of working people through the expansion of parliamentary representation. Among Chartists, the view that women’s proper place was in the home was common, and calls for women’s suffrage remained marginal. The mass base of Chartism dissipated in the 1850s, not long after the decline of Owenism.

British labor organizing during the rest of the nineteenth century took a male-dominated form, with its conservative approach to the “woman question” sometimes rising to the level of committed anti-feminism. As Taylor writes:

The Owenite call for a multi-faceted offensive against all forms of social hierarchy, including sexual hierarchy, disappeared — to be replaced with a dogmatic insistence on the primacy of class-based issues, a demand for sexual unity in the face of a common class enemy, and a vague promise of improved status for women “after the revolution.”

Meanwhile, a reformist outlook gained ground on the terrain of women’s organizing after the fall of Chartism and Owenism weakened the connection between socialist transformation and women’s rights and as more middle-class women concerned about respectability joined the movement. In the 1850s and ’60s, nascent and growing feminist groups took up John Stuart Mills’s call to remove obstacles to women’s entry into free competition on the same playing field with men. This was in contrast with the Owenite aim of abolishing social systems that were oriented toward such competition.

Political options reminiscent of these disappointing alternatives are alive and well today. The danger persists of marginalizing forms of oppression by identifying one fundamental cause of all social ills, whose overcoming will inevitably fix the rest, and modest claims for feminist improvements that are detached from a broader project of social transformation abound. Utopian thinking, on the other hand, can help us reinvigorate the connection between feminism and anti-capitalism.

The Right has caught on. Today’s conservatives do not merely resist change. Project 2025, for instance, is in many ways a textbook example of utopian thought, with an ethical vision that grounds its specific policy proposals and touches on every aspect of society, from family to trade, from gender to taxes. This imagined world is one they want to produce, not preserve, even if it’s wrapped up in traditionalist ideology.

The Left needs its own counterproposals: rich accounts of a transformed society that both help us decide what steps we should take now and keep us motivated for the long haul. I’m not suggesting all leftists should unite around one utopia but rather that debate and experimentation around ambitious aims for social transformation is an urgent political project rather than a matter of merely academic concern. Pace Marx and Engels, utopia’s radical potential has not yet been exhausted.