Riefenstahl Exposes the Nazis’ Favorite Filmmaker

Darkly influential, the cinema of Nazi propagandist Leni Riefenstahl is a powerful blend of art and propaganda. She’s now the subject of a new documentary that wrestles with the question of the culpability of a talented artist working for a vile regime.

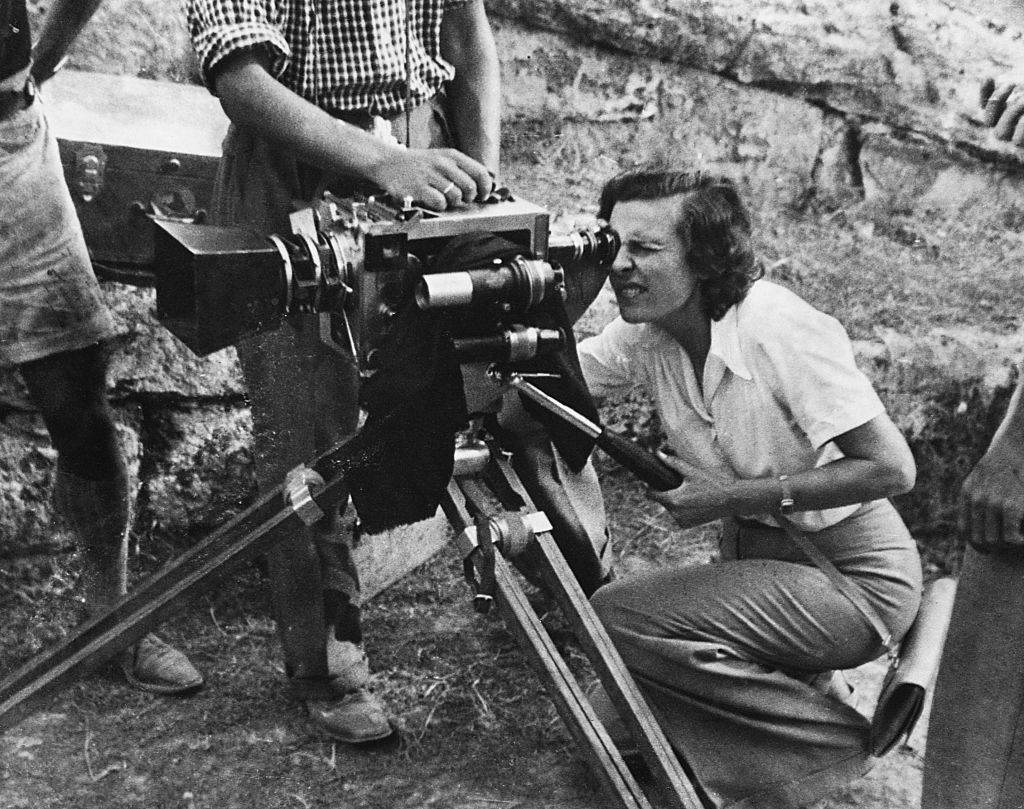

Between art and propaganda, real cinematic invention and atrocious kitsch, Nazi-era film director Leni Riefenstahl left behind a complicated record. A new documentary from Andres Veiel explores her legacy. (Corbis via Getty Images)

- Interview by

- Ed Rampell

When the Nazi elite is remembered, two prominent women likely come to mind: Adolf Hitler’s partner Eva Braun and dancer-turned-actress-turned-director Leni Riefenstahl.

Today, Riefenstahl’s cinematic influence is frustratingly undeniable. It was her striking and unsettlingly staged documentaries that first brought the pageantry of Nazism onto the world stage in works like Triumph of the Will (1935) and Olympia (1938), her film on the 1936 Olympic Games held in Berlin. Echoes of Riefenstahl’s aesthetic can today be seen in films as diverse as the finale to the original Star Wars to the work of legendary director (and passionate leftist) Orson Welles, who famously and reluctantly praised Riefenstahl’s cinematic talents on national television. Leni, who Andres Veiel calls “a prototype of fascism,” is now the subject of the German director’s new documentary Riefenstahl, now in theaters in New York and Los Angeles.

The Stuttgart-born Veiel has received many accolades, including winning the Venice Film Festival’s Cinema & Arts Award for the 115-minute, heavily researched Riefenstahl. The multitalented auteur’s filmography ranges from features to documentaries to the stage. His 2011 narrative movie If Not Us, Who? about Germany’s Baader–Meinhof Gang won two Berlin International Film Festival awards and was nominated for the Golden Berlin Bear.

Why is Riefenstahl making a comeback now? Tom Jacobson, playwright of Crevasse, a 2024 drama about Leni in Tinseltown, told Jacobin: “As the American government successfully manipulates public sentiment and churns out more lies than ever before in our history (which is saying a lot), it’s critical that we examine Leni Riefenstahl’s groundbreaking and skillful propaganda for the Nazis. How did she do it? What were the consequences? And how can we protect ourselves from fascist lies today?”

In this candid conversation, Veiel addresses similar points on ideology and aesthetics, Riefenstahl’s culpability, and the truth about just what she thought of the Nazi atrocities she witnessed. Andres Veiel was interviewed via Zoom in New York. This interview has been edited for clarity.

Who was Leni Riefenstahl?

Leni Riefenstahl was one of the most controversial filmmakers ever. She made films for the Third Reich. She was supported by Adolf Hitler himself. She made a film about the Nazi rally in 1933–34, Triumph of the Will. She also made a film about the Olympic games, Olympia, and she was world famous because of these films. Many people have praised her up to today as one of the most important filmmakers ever. Even Tarantino did. But I have a more critical perspective on her.

Tell us about the mystical “Mountain films” Riefenstahl starred in and directed.

She was, first of all, an actress in the 1920s. Quite a famous actress in many of the Mountain films. She also directed 1932’s The Blue Light. It’s kitsch; the storyline is very simple, but she got world famous with these films. She got an award at the Venice Film Festival and Hitler watched the film and engaged her, telling her: “You have to make all these films for our party.” And that’s what she did afterward.

She made Triumph of the Will and Olympia, and Hitler supported her and gave her all the opportunities, all the money she needed. It is a dream of every filmmaker to get all of these possibilities and chances and money and budget. That’s what she did and she got famous with these films.

Riefenstahl is known as “Hitler’s Favorite Filmmaker.” In addition to your documentary, Riefenstahl is also being featured in contemporary literature and theater — as a minor character in Daniel Kehlmann’s 2023 novel The Director and the female protagonist in Tom Jacobson’s 2024 play Crevasse, about Riefenstahl’s meeting with Walt Disney. Why do you think Leni Riefenstahl is making a comeback at this time?

First of all, for me she’s a prototype of fascism. Regarding her aesthetics, you can experience a renaissance of her aesthetics when you look at how the parades in Moscow are filmed – the low angle shots on Putin, the masses, the soldiers, all with the face up. It’s the aesthetic of the Triumph of the Will and the celebration of the healthiness, the supremacy of a nation. The contempt for so-called others, the foreigners, the migrants, who are criminals, lunatics. We are experiencing a renaissance of that ideology, of those aesthetics.

So, Leni Riefenstahl is something we have to deal with, with her films, with what propaganda means. That’s something we’ve got to learn. My film is like a magnifier on all these questions, it’s an invitation to look at Leni Riefenstahl, but also into the yearnings and longings for this aesthetic and also the ideology. It’s a warning out of the future.

Ray Müller made a three-hour documentary entitled The Wonderful, Horrible Life of Leni Riefenstahl in 1993. She was still alive at the time and interviewed for that film. You even use clips from it in your film. So why make yet another film about Riefenstahl?

It’s a very crucial and simple reason. We got access to her estate. Seven hundred boxes of unknown footage, of outtakes of films, of private movies. Her husband Horst Kettner and she filmed each other for decades. And nobody knew about these films. There are two hundred thousand private photos, so we could get another insight into her character, into her denials. To go beyond the legends and lies and look at why she had to lie. Why she had to repress so many, many – first of all, her responsibility being part of a regime which was responsible for sixty million deaths in World War II. And she made propaganda for this regime.

That was one of the reasons to make this film. I had a new insight into her life and character with a chance to look into her estate, her archive.

Was Riefenstahl ever a card-carrying, dues-paying member of the Nazi Party?

Well, she was not a member of the Nazi Party. It was not necessary for women to get party membership. But she was an intimate friend of the Reich’s propaganda minister, Joseph Goebbels. She was very close to Albert Speer, the minister of war. She was very close to Hitler, of course. Hitler supported her with lots of money. Whenever she needed something, she went to Hitler and cried and got another half a million.

For her, it was not necessary for her to become a member of the Nazi Party because she got what she wanted, achieved what she liked. Sometimes she had to cry, to shout, be charming, but in the end, she got what she wanted. So, we have the films.

Hitler fancied himself a painter. Did he see Riefenstahl as a sort of artistic kindred spirit?

Yes. He somehow trusted her talents. He had a feeling for her ability, her skills. He watched The Blue Light, he was a fan of it. And he felt, okay, she has this kind of talent, the skill of finding the right image to tell the story of being strong, being healthy, being better than — the storytelling of supremacy.

And the kitsch, which always means to magnify the beauty, to make even larger the strength and being stronger than – that’s always the ideology. And the disdain, the contempt for so-called weakness. This kind of kitsch he discovered in her work. For example, in The Blue Light – that’s why he asked her, “Please, you have to make our films, for our movement, for the National Socialist Party.”

On-screen, Riefenstahl describes experiencing Hitler’s speechmaking, which “enthralls” her. Was she ideologically, philosophically, a Nazi?

Yes. When you look at her story — the roots of fascism in her life didn’t start in 1933. You can find these roots in a breeding ground which starts much earlier. When you think about her education. She had a very brutal father. He wanted her to learn how to swim. He’d throw her into the water. She was close to death, about to drown and then her reaction in her written drafts of her memoir, wasn’t: “I have a nasty father.” Her reaction was: “I became a good swimmer.” So, in early childhood, she learned to celebrate strength, because being weak means being close to death. And she identified with the aggression of the father.

Something that is part of the fascist ideology is you are stronger than, you are cleaner, better than, it’s always a comparison and a separation — us and them. We are better because of our nation, our pride, and strength. And you always have the contempt of the other. That’s something she learned as a little girl. Normally boys are educated like this, but she was treated like a boy. When you think of the 1920s, all these people, the men she worked with during the Mountain films, they came out of the ashes of World War I: We came out even stronger — out of these cruelties, these horrors, we became stronger. The weak ones broke down, we became stronger.

And that was a good preparation to assemble under the flag of the Führer. So it’s the disdain, the contempt for weakness. Then the celebration of beauty, of the victorious, of the strength, and it’s part of the ideology. That’s something you can find in her films.

Can a fascist make great art?

No. Our film tells the story of why you can’t divorce ideology and aesthetics. Think of Olympia, the high-diving scene and other scenes, you always think, okay, it’s a film about sport. We’re celebrating people who are stronger and quicker than others, etc.

But the dark side, or you can call it the night side of this aesthetic, it’s also in the film, how the director of photography Willy Zielke was treated. He filmed the prologue, he broke down, he was admitted to a psychiatrist, and after some weeks he was forcibly sterilized. Leni Riefenstahl didn’t intervene.

Why? Because she followed the ideology of the Nazi Party and sick people are dangerous for the health of the people, the so-called volk. So, they have to get sterilized and she was supportive of the sterilizing of her director of photography. It’s absurd, but it’s true.

Triumph of the Will is Riefenstahl’s extravaganza about the Nazi Party’s 1934 Congress and Nuremberg rallies. She used some innovative cinematic techniques, such as vertical tracking shots in specially built elevators. Prior to Triumph, she had only made one actual film, Victory of Faith. In terms of cinema, Riefenstahl had mainly starred in and directed feature films in Weimar Germany, in particular, the so-called Mountain films, like 1932’s The Blue Light. Do you think that what made Triumph of the Will – which really consists largely of lots of blathering by Hitler and other fascist bigwigs – so aesthetically striking is that Riefenstahl really shot the Nazi rallies like a feature, with the aesthetic of fiction films, as opposed to using a more documentarian style?

When you look at the whole film, it’s a very long film, and it’s partly very boring. It’s lots of marching soldiers. For hours, you have the feeling people are marching through Nuremberg. But of course, you are right. Some elements, like the elevator scene, the way the low-angle shots on Hitler, the image of the Führer, is transferred to an audience in a way glorifying the Führer, treating him like a messiah. That’s the state of the art in the 1930s. It’s also still today: you can find the style of Triumph of the Will in Moscow, at the parades of Putin.

She was edge-cutting, putting out a standard of propaganda that’s apparent today. For me, that’s a challenge because it shows how deep, how far-ranging her impact is up to today. And that’s a warning, because we have to deal with the message of propaganda, even if it’s for another aim, another goal, but propaganda is propaganda. So, we have to deal with Leni Riefenstahl, and to analyze the means and methods of her films, to learn something about the propaganda films of today.

I have a terrible confession to make: I think Olympia is an objectively good film and I enjoyed most of it. Does that make me a bad person?

[Laughs.] No, you’re not a bad person. Maybe you have to focus on the dark side of the aesthetics, too. She’s a very good editor. You’re right – maybe she’s the best editor in the 1930s and 1940s, worldwide. But she made propaganda with this film for Adolf Hitler – he appears twenty-six times in Part I of Olympia. So, it’s also a celebration not only of sportsmen and sportswomen, it’s also a celebration of Adolf Hitler. He was very proud of this film. There’s always applause when Hitler shows up in the film.

Yes, she was a good editor. Yes, she was a good director, too. Because she decided which director of photography should shoot which kind of scene. She knew their skills and talents and said: “You are the one to film this and you’re the one to film that.” And that’s directing – she was a good director. But we have to focus on the ambivalence and not just praise her.

The athletes are depicted as Übermenschen, the Nazis’ ideal of supermen and women. The film does not show that German Jewish athletes, such as high-jumper Gretel Bergmann, were prohibited from joining the teams on the field. And how does Olympia deal with Hitler’s treatment of black track and field Olympian Jesse Owens, the American who won four gold medals, beating the Third Reich’s much-vaunted superior race?

It’s interesting to just listen to Leni Riefenstahl herself. Jesse Owens is in the film, but the way she depicts him is like he is a dangerous animal. Very ambivalent. And in a way also from a very colonialist perspective. The same way she treats, later on, the Nuba people in the Sudan. When you think about the scenes in the film when she throws sweets into the group of children, it’s like an animal feeding. She uses a stick to hit the kids.

That was very important to me to show. She’s treating the Nuba people like a marionette, pushing them around, using them for a specific framing. So, we have to learn how she manipulated all these images. You can call it the backstory of being very famous.

Some years ago, she was celebrated for the Nuba photos. There was an exhibition in Telluride. There was some sort of naive feeling with Leni Riefenstahl. So we have to be much more precise. That’s why I did this film.

Tell us about Riefenstahl and accusations of war crimes.

The crucial point regarding her actions in Konskie, Poland as a war correspondent is that she was an eyewitness of the first massacres of Jews. In the second week of September [1939, after the Nazis invaded Poland], four German soldiers were killed, and she wanted to film their funeral, the courageous German soldiers. The Jews were forced to dig their grave. They were hit with sticks and treated badly. She wanted to film just the courageous, clean German soldiers, not the dirty Jews who were digging the grave with their own hands. She was shouting, “Jews out of the image!” Some soldiers were shouting and suddenly the Jews ran away. One of the soldiers shot at them, then ten soldiers, twenty soldiers shot. In the end, twenty-two Jews were murdered.

She was responsible, not as somebody who shot, but somehow, she was a catalyst in this. Why? Because she gave the stage direction. And it’s written in the letter of an adjutant. That’s very interesting, because this letter tells the story about her involvement, being a catalyst in the massacre, because of the stage direction. That’s very interesting to me. Then you understand why she had to repress all her memories. She was lying when she said “I was not an eyewitness. I didn’t know anything about these atrocities.” Our film tries to look behind the lies, behind the legends. What are the necessities for her to lie, to deny the truth? This is one good example, to show her vulnerability being so involved in these atrocities.

She wanted to film Lowlands in Spain, but this was not possible. So she looked for people who had this non-German expression and she found them in an internment camp of Sinti Roma. They were very cheap, she didn’t have to pay for them. In a way they were also happy to escape the situation of being locked in the internment camp. After the end of the shooting most of them were taken to Auschwitz and killed there. Only half survived.

Actually, she tried to help them. But after the war she couldn’t tell the truth because she always said “I learned about the atrocities of the Holocaust and the killing of the Gypsies only after the war.” It was a contradiction. Somehow, she was in a trap. She couldn’t tell the truth, that she knew about the Holocaust, that she knew about the threat that all these extras would be killed, be put in Auschwitz. Somehow, she’s a tragic person.