The Economic, Political, and Cultural History of Menswear

Menswear expert Derek Guy talks to Jacobin about where Western men’s clothing traditions came from, how they have evolved, and how they're being continually reinterpreted.

Four men model the latest two-button suits of 1963 in front of a crowded Paris restaurant. (Bettmann / Getty Images)

- Interview by

- Dennis M. Hogan

Perhaps no other industry is as central to the development of Marxist economic thought as the textile industry, which was a major driver of the Industrial Revolution. When Friedrich Engels looked into the conditions of the working class in England, it was on Manchester, “Cottonopolis,” that he chose to focus. And when Karl Marx took readers into the “hidden abode of production,” he inquired first into the textile mills. The history of capitalism has, in a sense, always been the history of clothes.

Derek Guy is perhaps the most prominent contemporary commentator on traditional men’s clothing — where it came from, what it means, and what makes it look right or wrong. Guy, also known as “the menswear guy,” is a freelance writer who also maintains the menswear blog Die Workwear. Guy contends that the clothes we wear are shaped by politics, economics, and culture, and if we want to understand them, we have to start by understanding their relationship to history and the ways they still hold meaning.

For Jacobin Radio’s podcast The Dig, Dennis M. Hogan talked to Guy about his interest in clothing, where Western clothing traditions came from, how they have evolved, and how they’re being continually reinterpreted. They also discussed the changes sweeping the garment industry as well as the contemporary state of menswear. This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

The Rise and Fall of Menswear Blogs

When did you first become interested in clothes, and how did the internet in particular shape that interest?

When I became interested in clothes, I was not interested in clothes per se but interested in music. Anyone who grew up prior to, like, 2005 will know that, for a time, if you were interested in something — if you’re interested in sports or punk music or hip-hop or skating or whatever — there often came a kind of subcultural form of dress that you picked up almost intuitively. You wore a certain uniform to identify yourself as part of a group, but also adjusted that uniform a little bit to express that you were an individual within that group.

Like many young people, I went to clubs. I went to clubs to watch people dance, and they were almost entirely male affairs; 95 percent of the people in there were men who were also into dance. In that scene, there was a kind of subcultural form of dress. People wore Nautica, Tommy Hilfiger, Guess — and the most stylish of all wore Polo Ralph Lauren.

So I became interested in clothes by watching dancers and people in the music scene dress a certain way. Then when I went to Ralph Lauren, I was introduced to things like tweed sport coats and Oxford cloth button-downs and chambray shirts. It was only later that I realized that Ralph didn’t necessarily invent these things. Many of the original tweed sport coats came from Savile Row. The chambray shirts were originally workman’s shirts that were picked up by the US Navy. Brooks Brothers invented the original Oxford cloth button-down at the turn of the twentieth century.

So I kept digging and digging. By the early 2000s, I had discovered menswear blogs and forums. Through menswear forums, I fell in love with tailoring and all of these specific niche things, like rare Japanese jeans or whatever.

I want to touch on a little bit of internet history. People often observe that if you’re a brawler on sites like X, it’s because you earned your stripes in the early days of these internet forums. What was posting like in the days before Twitter?

In the early days, for me it was all blogs. There were hobbyist blogs: you had interior design blogs, music blogs, style/fashion blogs. These were all run by one person — rarely it’d be, like, two people — and they would upload this very specific interest of theirs, and they’d have a blogroll on the side where they link to other blogs. And there was an online community oriented around that.

Like a lot of people, I was reading a lot of music blogs at the time, and people would do these deep dives into soul music or jazz music, and then they’d rip some record that they have into an audio file, and you got to hear some rare EP or whatever. But for menswear, there were the blogs, which was a one-directional interaction; this person was writing and you were reading, and sometimes there’d be some comments, but the comment section was kind of whatever.

The real “interaction,” was on forums, at least on menswear forums. I was primarily on Styleforum, but I was also a member of London Lounge and visited Ask Andy About Clothes and some other forums. Superfuture/superdenim was the one for denim. There were tons of forums for all these specific styles.

Looking back, part of it was there was a small cadre of core posters who knew a ton, and — at least on the forums that I visited — they were often not very friendly to “noobs,” or newbies. You’d go there and you’d ask a simple question, and people would seem exasperated that you would even talk. So you had to hang around for a while to learn all of this stuff. But the nice thing about menswear forums at the time was that all of the people on these forums were super nerds, and there were super nerds in the sense that they also not only had intense interest in the subject, but they came at it from different backgrounds.

There were guys who had been buying bespoke clothes from Savile Row since the 1970s. There was a professional bespoke tailor; there were professional shoemakers, cowboy boot makers. There was a guy who did pattern-making for one of the largest US suit brands. There were guys that just read tailoring books. There were guys that read 1930s menswear manuals. They came at it from so many different directions. That was so pre-internet. That made the discussion so interesting, because you’ve got all these different perspectives from these super nerds essentially.

Over time, in my experience, the forums started to shift a little bit, becoming a little more commercial. There’d be more affiliate threads; more of the people that were new would be coming in. They tended to both be primarily interested in shopping and consuming a lot of information from the same sources. It became very homogenous. If you read all of the blogs and forum content from 2005 to 2012, by 2012, the person that was coming in was mostly looking for shopping advice, and they were regurgitating something that had been written on a blog post in 2007, which you already saw. So it was less novel.

Another interesting thing about that time period — from 2005 to 2012, 2015-ish — was that bloggers were shunned. They were looked down upon, and they were considered both not serious and low status, so they wouldn’t be invited to fashion shows. Brands wouldn’t really associate with them. They were considered not very professional. And out of that came a lot of bad information, because the person was so outside the fashion system that sometimes they would just get things wrong. But you got the undiluted, unfiltered, honest opinion of somebody, even if it was wrong.

Over time, as fashion brands realized that blogs could generate sales, they brought them into the fold. They would give them free clothes; they would say, “If you help us sell things, we’ll give you some money”; they would invite them to parties. Of course, when you’re invited to parties, you feel special and you want to be nice to the brand. So you say nice things about them later.

With time, the kind of purist view became a little bit more corrupted. If you looked at a menswear blog in, say, 2007, that [author] is a super nerd that is writing purely. Even in that one-directional exchange, where there’s very little interaction, at least you’re getting that super nerd’s opinion. And then by 2015, 2018, certainly today — there aren’t even blogs today. It’s all on Instagram now.

But these people would be invited to shows, they’d get free clothes and free sweaters, they’d get some kickbacks, and then it just became sponsored content. The thing that was great about blogs in the early days is that they were distinct from magazines, because many people felt that magazines had been co-opted by brands. In fact, nowadays bloggers are often worse than magazines because at least on some level — certainly if you’re writing for the Washington Post and New York Times — they enforce stricter standards. They don’t even allow you to take freebies. There’s some journalistic integrity.

The Birth of the Suit

You’re pointing us to both the old utopian promise of the internet, where it was going to give you access to all of these kinds of people who you’d never have access to in your normal life, as well as some of the ways the internet has been integrated into the larger economy of the fashion world.

First, I want to talk a little bit about history, because one of the things that I think people really appreciate about your writing and your posting is that you go out of your way to contextualize the language of clothing within its history. Maybe we can start all the way back in the seventeenth century, which is where you’ve connected the rise and decline of the suit to the birth of political liberalism.

Clothing choices are shaped on the moving tectonic plates of politics and economics as well as technology. The technology of the time influences what we can produce and how we dress but also the systems on which we build. Politics and economics define how we dress over time.

A good example of this is [provided by] looking at the political leaders over time, because they have the most choices in terms of dress. If you talk to a seventeenth-century peasant, they’re trying to fashion together whatever they can to cover themselves — although there were some sumptuary laws defining what people could wear depending on their station in society, which were still about protecting, to some degree, elite interests. But if you look at the elites at the time — if you look at English monarchs — many of them are wearing these incredible materials like pearls and gold. And they’re fashioning these clothes, using all of these systems of structure, to make themselves look almost otherworldly. The [goal] is to project the idea that this person is not of this earth, that they have some divine right to rule.

As you see democratic movements progress and people believing less in the divine right to rule, as the printing press takes off, as people reproduce printed material to criticize the ruling elites — you see many drawings making fun of how elites dress, to say that they are dressed ridiculously, that this kind of attire is unfit for someone who should be a steward of the country, and so on. But over time, the leaders of these countries in France and England started to dress more humbly. They were no longer wearing these kinds of incredible furs and silks and pearls. They started to dress a little bit more . . . not like the common person but a little more drab.

Beau Brummell had revolutionized men’s dress. Beau Brummell is a figure in Regency England who changed men’s dress by putting on what at the time was relatively simple attire for his station. Men who were interested in clothes were known as fops. They had these crazy powdered [wigs], and they wore this really elaborate clothing. Brummell pared it down to the simple navy coat, cream-colored breeches, and a very simple white cravat, which he actually spent a ton of time tying in the morning to get it to look just right, to give this idea that he didn’t necessarily actually care about his dress — that he just fell out of his bed and looked this way.

He’s often credited with changing men’s dress, which is true. The uniform that many men wear today, which is the navy sport coat and grey trousers and the white dress shirt and the cravat, which has become the necktie today, basically descends from Brummell. But Brummell was only able to do that at the time because there were already calls for more modest forms of dress. So when he advised King George, King George was open to the idea of Brummell’s view of fashion because there were pressures to dress a little bit more humbly, to focus on cut and restraint rather than going all out with this crazy clothing.

When you look at the changes in men’s attire over time, one story that I like to point to is the rise of the suit. Nowadays, when you talk about the suit, many people think of the suit as a very formal garment. It is basically the symbol of propriety and upper-classness. But there was something before the suit, and the thing before the suit was known as the frock coat, which was a much longer coat.

Men in high positions, such as those that occupied finance, medicine, and law, wore the more formal frock coat with a silk top hat, while people sitting lower on the professional and social ladder such as clerks, administrators, and working-class people wore a version of a garment known as the lounge suit. Most people, if they saw a photo of a lounge suit today, would say, “That’s a suit.” But it’s slightly different. It doesn’t look like what President [Donald] Trump or President [Joe] Biden wears today; it’s a little more of a rougher kind of utilitarian garment, but it is the baseline of how the suit came to be today.

It really took over throughout time because [some of the people] who saw their fortunes rise with industrial capitalism — the petit bourgeois, the clerks, the administrators — their clothes took on status and the upper elites, the people who were wearing the frock coats, were increasingly pressured to dress down. And they took on the new garment that had status, which was the suit. This also ties into religious beliefs to some degree, if you look at religious writings.

The frock coat that preceded [the lounge suit], Victorian dress, is famously all black. It’s very austere. And this comes out of the same moment when Brummell is making his reputation, something called the “great male renunciation,” in which men begin to give up patterns, colors, and ostentatious clothing and move toward a drab uniform.

Much of that is cultural. The rising bourgeoisie has a different set of values from the aristocracy: they’re serious, businesslike, austere, proper, moral, upstanding. In one of your essays on dress, you refer to the historian John Styles, who argues that “religious values for modest dress help mainstream the plain and straightforward suit into masculine wardrobes. The Methodists, led by John Wesley, encouraged followers to eschew ornamentation and extravagance.” The Quakers also were against ornamentation and extravagance. So was this great male renunciation just the triumph of boring, no-fun Bible beaters?

If you want to simplify it, that’s true. The suit also rose around the world because of the Second British Empire. You can track these changes; it’s easy when you look at the dress of other cultures before and after the rise of the Second British Empire, including dress in France, India, and China. All of these places became a little bit more drab because, one, the British Empire had enforced administration systems in some of these countries. So to work in the administration, you had to adopt a uniform; that was part of it. But also this kind of attire took on the idea of power and status.

There’s a really good writer, W. David Marx, who wrote the book Status and Culture in which he claims that almost all culture can be explained by status games, and that our pursuit of status is what drives culture. In that sense, you can understand that as the Second British Empire rose, more people adopted this kind of Victorian, drab British uniform. I will note that in Western culture, there’s long been a prejudice against dress. When you read Karl Marx’s writings, for example, he uses the term “fashion” as a pejorative. The story of the emperor who has no clothes is a story about a vain man who seeks flattery.

There has always been a bit of a bias against fashion in Western culture. It’s seen as vain and frivolous, fleeting. Historically, since women were pushed out of “serious” fields such as academia, politics, and law, fashion was left to women. Men were expected to have “higher” pursuits, and so they shunned fashion. In that context, Christianity specifically, there were these ideas. The Quakers, the Methodists, had this idea that to demonstrate moral and intellectual virtue, one should dress very modestly and humbly. And the more you rejected fashion, the more intellectual and morally virtuous you were.

When you understand that, the suit rose, one, because of the rise of the Second British Empire, as I mentioned. And two, because it was worn by what at the time was a version of the working class. It conveyed this idea of honesty and — kind of like how we see jeans today — this idea of ruggedness, masculinity, virtue, things like that. It also fit in very well with religious views on clothes, which is that you should dress more humbly. The suit was considered more drab and humble than the more formal frock coat. The frock coat, for example, had four panels at the back to give it this very shaped silhouette.

The suit, by contrast, is much simpler. It consists typically of just four panels: You have the two front panels that would cover your chest. That’s the part that you would button. And then, at the back, it’s typically two other panels. And generally speaking, the back is much straighter and less shapely than a frock coat. This was considered . . . I wouldn’t go as far as to say it was the cargo shorts, but it was, kind of, at the time.

To give an example, Keir Hardie, a founder of the British Labour Party, caused a great stir on his first day in parliament. He was elected to represent a working-class district of England, and he arrived to parliament wearing a tweed suit and [a deerstalker] cap. At the time, MPs wore the frock coat and a silk top hat. He wore that to signal his allegiance to the working-class constituents that he was elected to represent. The British press was scandalized.

It just demonstrates that what is formal and what is gentlemanly, in our understanding, was not always considered so. A proper gentleman of the 1800s would have considered the suit to be not proper, respectful garb, and would instead wear the silk top hat and frock coat.

It makes sense when you think about the status that different materials have too. When you think about what it takes to source, for example, the silk to create a silk top hat versus the simple woolen cloth that would have been relatively easy to come by in England at the end of the nineteenth century, it makes sense why one is informal and one isn’t.

Yeah, one takes much more work, craft, and expensive material to produce.

Menswear and the British Empire

You argue frequently that if we want to understand tailoring as a language, we have to understand its origins in British business and leisure culture: the difference between the suit that you wear in town and the tweed that you wear in the country.

But British culture didn’t get exported around the world by coincidence. It was exported by colonialism and empire, and it’s impossible to talk about the British Empire’s manufacturers without talking about cotton. And of course it’s impossible to talk about cotton without talking about slavery.

Manchester’s textile industry grew first around the exporting of fabrics to Africa, where they were used as trade goods in the slave trade. According to the Guardian, up until 1770, one-third of Lancashire’s exports were used in the slave trade in West Africa. In 1788, Manchester exported £200,000 worth of goods a year to West Africa. Later, when Manchester became “Cottonopolis” it was American slave-grown cotton that the mills transformed into textiles.

How did the integration into the economy of slavery shape men’s fashion, either from the point of view of style or production? And how do people who think and write about men’s fashion today, especially the traditional fashion that grew out of these nineteenth-century references, grapple with the imperial heritage of so many of our clothing traditions?

The production of clothing at the time was heavily on the back of slavery. And when we talk about the rise of the Second British Empire, we’re talking about colonialism, imperialism, guns. The history is undeniable. To answer the question of how people today grapple with it, I would say that tailoring — specifically the suit — is not just that history. There is that history, but there are also beautiful parts of that history, of how these clothes were worn and adapted and expressed by people of different classes.

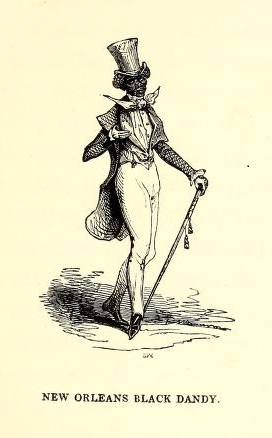

The Metropolitan Museum of Art recently had their Met Gala, which raises funds for the museum’s Costume Institute. And from now until October, if you go to the Met’s Costume Institute, you’ll get to see their exhibition on the black dandy. If you can’t make it to the Met, you can buy the book Superfine, which is the book that accompanies the exhibition, or the book that inspired the exhibition, Slaves to Fashion by Monica Miller. Both are really great reads.

In Superfine specifically, you can see how black dandies took that language, just as you and I are using language right now, that was once used by slave owners. But they tweaked it, and they tweaked it so that it was still coherent — you still understand, “Oh, that’s Ralph Lauren, and Ralph Lauren represents wealth” — but they’re also using it in ways that represent their own identity.

I’m glad that you brought up the black dandyism exhibition. We’ve touched on a few of the figures who are important in the history of dandyism as an orientation toward clothing: Brummell, and then that attitude’s adoption and appropriation by people who wear clothes across the black diaspora.

One of Brummell’s great admirers was the French writer Jules Barbey D’Aurevilly, who wrote, “Dandyism springs from the unending struggle between propriety and boredom. Accordingly, one of the consequences and principal characteristics, or rather the most general characteristic of dandyism, is always to produce the unexpected — that which could not logically be anticipated by those accustomed to the yoke of rules. Eccentricity is unbridled, wild, and blind. It is the revolt of the individual against the established order, sometimes against nature. Dandyism, on the contrary, while still respecting the conventionalities, plays with them.”

It seems like that sums up the Brummell attitude as well as the appropriation of something like Ralph Lauren or tailoring by black dandies in Kinshasa. So is dandyism like the revenge of the aristocratic ethos, sneaking back into the fashion world of the bourgeoisie? Or is it some sort of entirely new phenomenon?

When we talk about dandies, often we are talking about people like Oscar Wilde and Brummell and these great figures that loom over history and change the way men dress and the way we think about clothes. There’s a new book coming out this September by Peter Anderson, called The Dandy: A People’s History of Sartorial Splendor. The great thing about this book is that it takes the idea of dandyism away from these famous aristocratic figures and talks about it in the context of everyday people — like the Congolese sapeurs in postwar France, who had used attire to define their own identity in the wake of what happened after World War II. The book talks about the black dandies’ history in the United States, and so on.

When I was reading that book, it crystallized for me why there are so many weirdos on these menswear forums. To some degree, these are people . . . I don’t know if they’re challenging ideas of like hetero masculinity at the time — to some degree they are, because throughout this history, as we know, there is this idea that men should not necessarily be into clothes. So if you’re interested in clothes to some kind of undue degree, or if it’s detectable, there’s some suspicion often cast on your gender and your sexuality.

Tom Wolfe wrote a really beautiful essay called “The Secret Vice” about this in 1966. It was published in the New York Herald Tribune. He talks about how men would rather be seen with a pornography magazine in public than a clothing catalog. I think he’s exaggerating to some degree, but he’s actually not that far off. It is true that the dandy is often bucking some convention of the day, if only because their dress tends to be, if not extravagant, at least unusual or noticeable.

Charles Baudelaire famously wrote that the dandy is the last flicker of decadence at a time of basically declining empire. If you go to Anderson’s book, it takes the story away from the idea of these really eccentric, rich figures and talks about how men of more modest means, some even poorer, have used clothes to express this decadence.

Part of what you argue often is that clothing is a language. And part of what language allows you to do is to take units of meaning and to recombine them — to combine them in ways that could be very conventional, but also to combine them in ways that could be unexpected or original. The only real mistake is to not really know how the language works. Dandies know how the language works, and they’re very committed to innovating within it.

Sometimes people ask me about how fashion trends arise. Noam Chomsky is known for being a leftist critic, but he’s actually, professionally, a linguist. He’s famous for the phrase “colorless green ideas sleep furiously” as an example of a sentence that is grammatically correct but makes no sense. When you think of outfits as language, that you combine them using existing words and put them in the correct order to express something — that you’re rugged or refined or whatever it is — that is what makes an outfit good.

The dandy, or someone who’s innovating in some way, is usually someone with some type of cultural capital. When you think of slang, for example, how does slang come about? When you think of how new fashions get created and how people take existing words and flip them in new ways, you can think of clothes as similar to language, in that someone with cultural capital took something existing and turned it into something else, to mean something else. Someone takes an existing style — often like a work garment, like work boots or a work jacket — and flips it to mean something else. And since they have cultural capital, the style is now considered cool, and it gets put into the mainstream through some other medium, like a movie or music video.

Before we leave the historical crimes of the British Empire in the past, I want to ask one more question about the relationship between South Asian textiles, in particular, and modernity. Because when the British colonized India, they were there in part because they had this incredible desire for fine South Asian textiles like chintzes and muslins. But they destroyed the domestic textile market to create a market for their own exports.

This history led to one of these classic stories of clothes, empire, and fashion, which is the production of Madras cloth. How did British colonialism in India combine with local traditions to create this unique fabric? And then, how did it come to be seen as the epitome of preppy style here in the US?

Madras is typically a pure cotton. It’s typically handloomed. So the cloth has a sort of airy, slightly uneven quality to it. It’s because it’s so reliant on human labor. The fabric is not as smooth and consistent. This was also part of Gandhi’s political movement, in which he encouraged Indians to spin their own yarn, loom their own fabric, and use that fabric to make their own clothes so that they wouldn’t be reliant on British textiles.

Madras is an airy cotton that’s made for the Indian environment, which is very hot. But they dyed it in these really brilliant natural dyes that gave the fabric a very vibrant color. It kind of looks like the Scottish district checks, but they are tartans essentially. But the Madras checks are distinct in that they’re even brighter. I would describe [them as having] a happy color. Madras is also dyed with vegetable dyes, which doesn’t make it very colorfast — “colorfast” meaning how well the dye holds on to the yarn.

In fact, as India was making this cloth, some of it was exported to the United States, where Brooks Brothers, according to lore, had used this to make colorful summer shirts because it would be suitable for a hot, humid climate. As the story goes, they put these shirts on the sales floor, and one day, one of the customers came back into the store hopping mad. That person complained that when they had put their Madras shirt into the wash along with their other clothes, the color bled out and dyed their other clothes. Remember, this is a natural vegetable dye, so it doesn’t have the industrial qualities that you would get from a synthetic dye, or the kind of clothes that you and I are mostly familiar with. After that, Brooks Brothers stamped all of their Madras “Guaranteed to Bleed.” So it became this kind of desirable quality.

That material was used for shirts, and a heavier version of that material was used for jackets and sometimes pants. And then a company called Winston Tailors had also used cut-up pieces of Madras to make patchwork Madras, which was sometimes used for shirts, but mostly for jackets and pants.

The funny thing is, a lot of that language is lost today. Oftentimes on a menswear forum, you’ll get someone who’s new to clothing, and they’ll see that for the first time, and they’ll be like, “Are people serious? That is a really ugly garment.” Because when you look at a patchwork Madras jacket, it looks absurd, because it’s all of these riotous, happy colors cut up and stitched together into this Frankenstein monster jacket. But as we were talking about earlier, these clothes took on meaning because they were worn by white Anglo-Saxon Protestant elites sometime between the early [twentieth century] to about the 1970s. They took on meaning — wearing that demonstrated that you were part of the class of people whose lives kind of sat on a conveyor belt that moved them from Andover to Harvard to Wall Street. So it became canonical preppy style, but originally the fabric is from India.

Around the World in Textiles

This is a great demonstration of the ways that all of these fabrics have these contexts that they have emerged from. They have histories; they come from places; they’ve been developed according to traditions or to suit particular needs. Maybe we could do a quick round of naming some fabrics and describe what they’re used for, where they come from and their histories. Maybe we can start with tweed.

It’s my favorite fabric. There are basically two ways to make fabric. Generally speaking, there’s a worsted and there’s a woolen. A worsted is when you comb the hairs prior to spinning them, which removes the shorter hairs and sets the hairs parallel to each other. Woolen is when you don’t comb the hair, so the hairs are sticking out in all directions.

Tweed is typically a woolen, which makes it more insulating because there are more air pockets. There are two contesting stories of how tweed got its name. One is that it got its name from the River Tweed, the area where some of this fabric first originated.

The border between England and Scotland.

Yes. The other is that a cloth merchant sold a bolt of cloth of woolen twill to somebody, and they wrote on the receipt kind of messily. And the person who received it mistook the writing “twill” for “tweed” and then labeled it tweed.

We don’t really know where the word originally comes from, but it certainly comes out of the Scottish Borders area, where people historically wore this really thick, rough woolen cloth. Historically it would have been pretty drab, although nowadays it can sometimes come in bright colors — but it’s still usually pretty drab. It’s worn because of its durability.

If you go to thrift stores today, you can still find tweed jackets, assuming they haven’t been eaten through by moths. They’re usually still pretty intact because it’s a really tough fabric, which is because of that woolen quality, the hairs sticking out in all different directions. There are all these air pockets, which makes it pretty warm; I would say any temperature below 65 degrees, you can usually wear a tweed of some weight. The weight typically starts around thirteen or fourteen ounces. You don’t typically find lightweight tweeds because to get a lightweight fabric you usually have to use a worsted yarn. We associate tweed now with the autumn and winter months naturally, because you need it to be a bit cold to wear it.

We also associate it with the country historically. A lot of men’s dress norms, at least when we’re talking about classic tailored clothing, are derived from England and specifically aristocrats — essentially the kings, princes, and the people that would have been born into money. Those people typically had wardrobes divided in half.

Back then, clothes were dictated by the idea of time, place, and occasion. If you were to go to London to do business, you’d wear a dark worsted suit — worsted meaning that very slick kind of yarn. And that would be in either navy or gray. You’d wear a white dress shirt, a dark tie, and black calfskin oxfords. If you were to go to the country to hunt pheasants, ride a horse, or hang out on your estate, you would wear some type of tweed. Usually that’s in an earthy color — olive or more often brown, sometimes gray — and you would pair it with whipcord trousers, a tattersall shirt, a wool tie, and Scotch green shoes.

There’s a really good scene in the Netflix series The Crown, where Margaret Thatcher and the Queen interact. Margaret Thatcher grew up upper-middle class, the daughter of a businessman, and in a city environment. She basically only knows about politics and Westminster and that kind of life. The Queen, of course, is obviously the Queen, and she’s an aristocrat. She grew up in the system where people had wardrobes divided by city and country. There’s a scene where Margaret Thatcher visits the Queen at one of the Scottish estates, Balmoral. She arrives, and because social interactions are what they are and people live certain lifestyles, and it’s very clear if you’re not of that background, she is by default put through a series of tests.

One of the tests is when she’s invited to go hunting with the Queen and some of the royals. She walks out to meet the family that morning and everyone is wearing tweed and wax Barbour jackets and hunting boots. When Margaret Thatcher emerges from the castle to meet the Queen, she’s in a delicate blue dress and basically business shoes. And everybody in the royal family looks at her like, what are you doing? This is so odd. She’s obviously an outsider.

They get into the car, and they talk about their childhoods. And as they’re going through the countryside, the Queen quips at her, saying that next time you come on these trips, maybe you shouldn’t wear a bright blue dress because the animals that we’re stalking will see you. Maybe you shouldn’t wear perfume because the animals can smell you. And then as she’s talking, Thatcher stumbles and lets out a yelp, and then the Queen says, maybe you also shouldn’t make noise because the animals can hear you. So there was a certain logic to these clothes: people wore really tough clothes and earthy colors so that they could hide in the environment and shoot an animal.

The scene ends with them going back to the estate and the royals having tea. Thatcher and her husband come into the room, and the husband is wearing a tuxedo. Everyone is surprised because a tuxedo at the time would have been worn for dinner, and they’re just thinking, why are you wearing dinner clothes at teatime? This gets back to the idea that clothes [were determined by] by time, place, and occasion. You wore certain things to go hunting; you wore certain clothes for dinner; you wore certain clothes to have afternoon tea. By constantly failing these tests, you demonstrated. . . . If you hang out with a new crowd and they all speak a certain kind of slang, it’s obvious when you are clumsy with the slang, the slang is not natural to you, or you just don’t speak the language.

This [brings us] to two works that you’ve quoted in some of your writing. One is Pierre Bourdieu’s Distinction. Which doesn’t only talk about how upper-class tastes and practices govern what’s considered to be good taste but also talks about how there is sort of a hierarchy of people who have good taste: those who are born into it, for whom it seems natural, and then those who acquire it through learning.

In Bourdieu’s example, it’s the difference between the person who learns to appreciate modern art at school and can explain why modern art is good, and the person who grows up around it and who automatically thinks that modern art is good because that’s what they have absorbed as their taste.

That’s something that I’ve learned over the course of my life, that unfortunately, you just can’t escape who you are. You are who you are. I remember I had a conversation with a friend of mine who happens to be very wealthy, and I’m not wealthy. My parents are refugees from Vietnam. I asked him once what watch I should get, a recommendation. He has really excellent taste. And he said, “Why don’t you get a Rolex Explorer? Because that’s more of an intellectual watch.” I think he basically meant, you’re kind of a nerdy dude.

Which made me realize, as I’ve gotten older, you can’t escape who you are. You know, if you’re middle class, you come off as middle class. If you’re nerdy, you’re nerdy. You are who you are, and your taste kind of reflects that.

Totally. So we’ve knocked off tweed. How about this one you talk about a lot — Shetland wool?

There are many different types of wool. It’s not just sheep. You can get garments made from Angora, a kind of rabbit hair. I’ve seen people make sweaters out of cat and dog hair.

But when we talk about wool clothes, we are typically talking about sheep. However, there are many different types of sheep. Cheviot produces a very curly kind of hair. Cashmere is taken from a cashmere goat in Mongolia. And Shetland is a type of sheep that grows on the Shetland Isles, and the cold weather produces a very coarse kind of [wool] . . . not as curly as the Cheviot sheep’s but a lot of these animal hairs have a natural kind of crimp in them, kind of scratchy — not terribly scratchy, but it’s not super soft either.

It’s sometimes used for jackets; it’s rarely used for pants, because pants are more likely to sit against bare skin. What you’ll sometimes see is a Shetland tweed. Lovett is a mill that produces some really nice Shetland tweed fabrics. But since the hair is kind of thick, you get very spongy fabrics more often. Where people are going to encounter Shetland is in the form of a sweater. I love Shetland sweaters. They are again a little bit coarser, a little bit rougher. It’s not something that most people would want to wear over a T-shirt. You could probably wear certain cashmere sweaters over a T-shirt; a Shetland knit requires a long-sleeved button-up shirt underneath.

Historically, as the story goes — again, this is mixed with marketing lore, so you have to take this with a grain of salt — as Brooks Brothers tells the story, when they imported Shetland wool sweaters from the British Isles, they arrived at their stores and customers would buy them. Occasionally these customers would complain of a fishy smell on very wet days. And supposedly this came from the fact that many of these sweaters were knitted in the home, sometimes in the kitchen, where women would be cooking fish. Is that story really true? I don’t know. It’s just a charming thing that’s passed around. But it is true that in this time period, and especially around the Scottish Borders and throughout England, there’s a lot of cottage industry, so oftentimes people were sourcing clothes from a company that had a network of outworkers that would work from home.

The Shetland sweater, specifically because it was imported from Britain and then sold through Brooks Brothers — Brooks Brothers’ original customers were typically people in urban areas like Boston and New York, and they typically were white, upper-middle-class people, WASPs who came from well-to-do backgrounds. Since it was worn by those people, it became somewhat of a status symbol.

The classic Shetland sweaters tend to feature a saddle shoulder, which means they don’t have a vertical shoulder seam. It has this shoulder seam that goes halfway up to your arm and then cuts toward your neck. These sweaters were sold at J. Press, Andover Shop, Brooks Brothers; they were worn by Supreme Court justices, lawyers, bankers, well-to-do people, and so on.

It’s a good value because you generally see Shetland sweaters retail for between, I would say, $125 to $250. Sometimes, depending on the company, you can go up to $300, but I would say around $200 to $225 is what you can expect to pay for a genuine Shetland knit made outside of China — made in England or Britain somewhere. I think they’re a good value because it’s a harder-wearing sweater, whereas if you were to buy a $150 or $200 cashmere knit, oftentimes because cashmere is such an expensive fiber, that company will cut back on the material. They’ll knit the sweater a little more loosely, so then it’s prone to stretching out. When you’re buying a Shetland knit for $200 or $225, it’s not a cheap garment by any means, but it will last you a long time.

Brooks Brothers and American Fashion

Since Brooks Brothers has come up a few times and no single American brand is more associated with American tailoring than Brooks Brothers, which dates back to the early nineteenth century, how did the company come about? How did their invention of the off-the-rack suit change the course of American fashion? And how did that particular style, the Brooks Brothers look — starting with the No. 1 Sack Suit — become the key reference for American menswear?

Brooks Brothers was started by Henry Sands Brooks in 1818. He opened a store in New York City. The very first people who he hired were typically German immigrant tailors. Most people that made clothes in the United States tended to be newly arrived immigrants, and at that time it tended to be German immigrants who had tailoring skills.

Before the invention of ready-to-wear, most men had clothes made for them, either in the home or, if they could afford one, by a tailor. There was some ready-to-wear before this period, but it tended to be relegated to workwear stuff that would be worn by slaves and then lower working-class people, like miners and sailors and whatnot. People who would be working in what would be considered bourgeois society, like clerks or administrators, typically had clothes made for them.

Brooks Brothers invented the first ready-made suit. The very first ready-made suits were pretty rough. They weren’t very good. In fact, Brooks Brothers got into trouble because they supplied clothes to both sides of the Civil War, and some of those clothes ended up falling apart and dissolving in the rain. The term “shoddy” comes from that period where those fabrics were sometimes made by sweeping up the kind of leftover stuff that would be on the ground at the mill and then gluing them together and making this garment, because they had to make so much stuff for both sides. So once these soldiers were out marching in the war, if it rained, the suits would fall apart. The soldiers had these really funny songs that they sang about Brooks Brothers’ crappy clothes. The US government eventually sued Brooks Brothers for selling them these crappy clothes.

They were more mad about the clothes being bad than they were about the fact that Brooks Brothers was selling the clothes to the enemy.

Exactly. But over time, the system got much better. One of the reasons it got better is because Brooks Brothers, as well as other regular manufacturers, got the body measurements of a wide range of people, from people who were forced to enlist in the army.

The army would measure people. They figure out your shoulder width and your chest size and your waist size. And through all of this data, Brooks Brothers was able to figure out your likely height, waist size, stomach size, and more, based just on your chest size. So if you have a size 38 chest, you probably have this for the shoulder and this for the waist, and you’re probably this height, and so on. This is how, over time, ready-to-wear work was improved.

The No. 1 Sack Suit, which is what Brooks Brothers called this new model, was debuted [around the turn of the century]. The hallmark of that style was a soft shoulder. You have to contextualize this all within the time period. If you were to pick up a No. 1 Sack Suit today, most people would not consider that a soft shoulder. But in 1901, that was considered a soft shoulder, meaning it had less padding in the shoulder.

Especially compared to the frock coat, which is so structured.

Yes, exactly. So first, it had a soft shoulder. It also had a hook vent. If you look at suit jackets, they typically either have side vents, which are the slits that go up the back, but a side vent means two slits toward the sides — or it had a hook vent, which means a center slit. The Brooks Brothers’ version had the center slit that was originally designed for horse riding, but they also cut into it a little bit to kind of create a hook.

The most telling part of the No. 1 Sack Suit was that it had a dartless front. If you look at British tailoring and Italian tailoring, you’ll typically see a line that runs right below the breast pocket down to about the hip pocket in England. In Naples, Italy, tailors will extend it all the way to the hem. A dart is basically a way to cut the fabric and then sew it together to create shape. English and Italian tailors will put a dart on both sides of the front, running from right about your rib cage to the pocket, and Neapolitan tailors will extend to the hem to create a curve that will hug your body a little bit more. The American sack suit doesn’t have a front dart, so the sides are a bit straighter.

The other thing I would note, and this is a little bit more obscure, is that American clothing manufacturing had always been more industrial than its European counterparts. When you construct a suit-jacket lapel, there’s the front fabric and then the back fabric. Since you can’t just have a raw fabric edge sticking out, the edge has to be folded in and then stitched together to finish that lapel. A tailor or a manufacturer will also have to stitch that down so that the lapel doesn’t curve to the wrong side.

In Europe, they’ll do that by hand, using what’s known as a pick stitch — which means you’re basically picking up layers of cloth and then pricking them through to stitch those four layers down. Brooks Brothers used a machine stitch. So if you look at a British-made or Italian-made high-end suit, you’ll see very gentle pinpricks that basically go down the line of the lapel. On an American suit, you’ll see a straight line of stitching, and that indicates that it was sewn by machine and not by hand.

Today this is complicated a little by the fact that they also have machines to imitate the handmade pick stitch. But generally speaking, if someone is making a true sack suit defined by what Brooks Brothers put out, they’ll even imitate the machine stitching along the lapel. I think it’s interesting in the sense that this was the beginning of the kind of democratization of clothing.

What we were talking about earlier, the painful history of tailoring, cotton-picking, slavery, British imperialism . . . I would say that there is this other part of the American side of the story. One way to conceptualize the evolution of men’s clothing is that dress often follows who we consider matters in society. So in the 1800s, you had all these upper-class gentlemen who were wearing frock coats and top hats. By the turn of the century, as the bourgeois class started to see their fortunes rise with industrial capitalism, their clothes took on meaning. You start to see the rise of their uniform, which is the suit.

It goes without saying that we are specifically talking about white males, usually of a certain background. We’re not talking about miners or sailors and so on. We’re not talking about black Americans or Chinese Americans or any of these people. We’re talking about white American males that come from middle-class and bourgeois backgrounds. Their dress started to take on status, such that the factory owners and the managers of those factories wore a similar uniform. That development demonstrated that a new class of people started to matter in American society, which is the white male bourgeois.

The sack suit is also interesting in the sense that the garment is factory made. It’s not bench-made — made by a tailor sitting at a bench. It’s made in a factory. It features straighter sides. The lapel, generally speaking, takes less time to produce because you’re doing a machine-stitch edge instead of a hand-picked edge. So it’s a little bit more of a democratic, affordable garment. We now think of that time period as regressive. But that was kind of a progressive part of that moment, at least more progressive than what it was before.

So the No. 1 Sack Suit basically carried a certain class of men from the hopping jazz clubs of the 1920s, through the Great Depression, and onto the Ivy League campuses of a booming postwar America. That is how that specific uniform took on meaning, specifically the sack suit and the white button-down shirt, which is basically the shirt that this class of Americans would wear.

Sometimes people use the term “button-down” to refer to a shirt with a button front, which is sometimes called a coat front, which is not actually technically correct. That would be called a button-up shirt. A button-down shirt refers to when the collars button down onto the body of the shirt, forming kind of an S-shaped curve. That was also introduced by Brooks Brothers at the turn of the twentieth century, inspired by this kind of collar invention worn by British polo players.

So they wore the Sack-cut suit with a button-down shirt, often a striped tie. The striped tie went in the opposite direction of the British ties. On the British ties, their stripes went in a certain direction. Brooks Brothers didn’t want to seem like they were copying the British, because the British stripes actually referred to associations in the British military, or certain schools.

They had their stripes running in the opposite direction, and then they would wear things like long wings or gunboats, which is a type of wingtip shoe. Or they would wear penny loafers or tassel loafers. They would wear cuffed trousers or flat-front trousers.

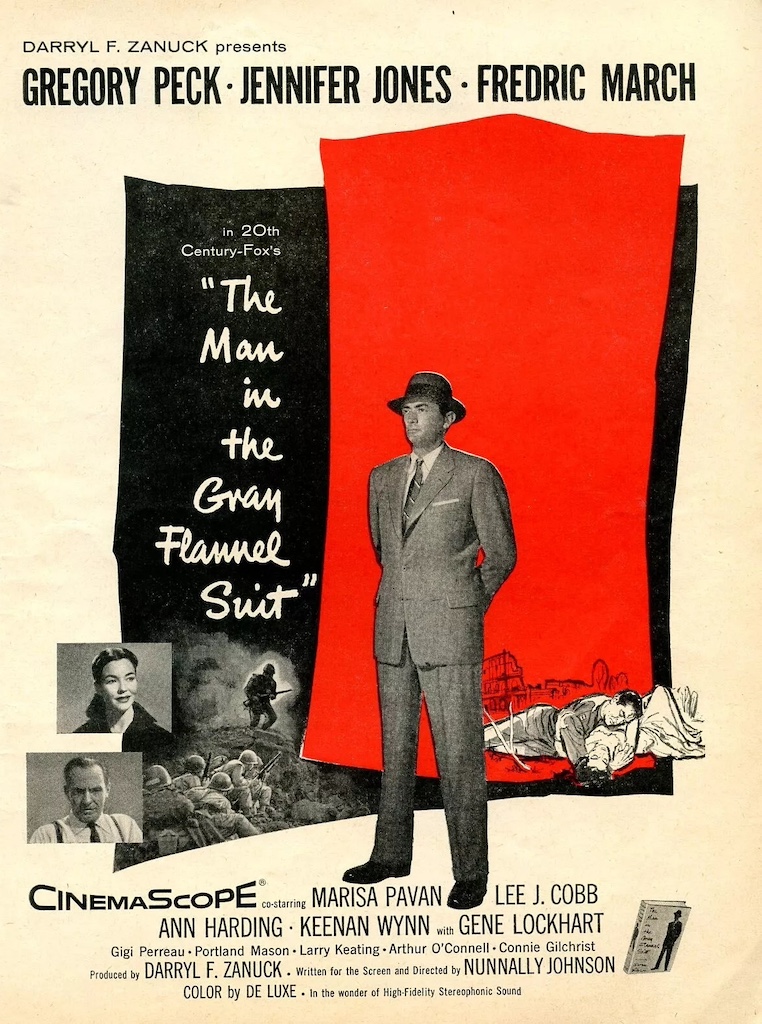

The easiest way to conceptualize this is that this was the uniform in the film The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit. Gregory Peck in that film actually wears a suit from Huntsman, which is a tailor on Savile Row, so that shoulder is very structured. It’s not soft at all. But that uniform represented basically a certain kind of man.

That man, especially in the postwar period, was a white man who went to war to fight in the trenches of Europe, came back and was afforded a free college education through the GI Bill, went to college and then came out of college, and got some type of corporate job, which he used to then pay for, like, a nuclear family that he raised behind a white picket fence. Basically, that kind of lifestyle, that system, that conveyor belt was basically the socialization of a new class of bourgeois.

Since Brooks Brothers had dressed American section of the elites, their clothes were copied throughout the United States. There are all sorts of clothes that offer their version of the sack cut, their version of the button-down collar.

There were other two important clothiers at the time, which were J. Press and the Andover Shop, which clothed students at these elite colleges like Yale, Harvard, Princeton, and so forth. Those students would have worn some version of Brooks Brothers when they went to Andover and all of these preparatory schools that landed them in the Ivy League colleges. But by buying their clothes from the Andover Shop and J. Press, which were located near the campuses, they could avoid going all the way to New York to get their clothes from Brooks Brothers. They would just buy the Brooks-y Ivy style from the local campus clothier.

When those people graduate college, they continued to wear that type of clothing that they had worn at Andover and Harvard. They would wear that clothing while working in Washington politics and law, New York finance.

That’s what Brooks Brothers represented. I would say that class of people started to fade from real cultural and political influence during the 1980s. As I mentioned, I talked to David Marx, and we talked about what power meant in different eras, [what it meant] to demonstrate cultural sophistication, political power, economic power, and cultural capital.

If you were to demonstrate that in the 1980s, it might be about knowing how to talk about fine art and literature to George Plimpton at an invite-only New Yorker party. In New York today — first of all, I don’t even think there’s anyone like George Plimpton. The people that descend from that class don’t even dress like George Plimpton anymore. So that kind of character is gone. But certainly to demonstrate that now, according to Marx, it would be more like talking about cryptocurrencies and Twitter discussions with Mark Zuckerberg or Elon Musk at an MMA fight or something. It would not be a New Yorker party.

In fact, even saying that you care about talking about fine art and literature to George Plimpton at a New Yorker party demonstrates that you’re not part of a class that has any relevance. You’re basically like a menswear blogger. You know what I’m saying? Like, Mark Zuckerberg does not give a flying hoot about that stuff. And Elon Musk and [Jeff] Bezos. All of those people — they don’t come from that class of people. The only person in any kind of semi-high position that comes from that class of people in recent memory is like Mitt Romney — or who’s the prosecutor that did the Russia report?

Robert Mueller.

Robert Mueller comes from that background. John Kerry comes from that background. All of those people are on the sidelines of politics now and age-wise they are on their way out. The people that hold power did not grow up in that WASP-y society.

The important thing to understand about Brooks Brothers’ place in that history is that if we think about clothing as social language, Brooks Brothers gave American men their ABCs. There’s a brand called Aimé Leon Dore, which is a super-hyped — I guess you could kind of call it “streetwear,” although that’s kind of a loaded term nowadays — and they do tennis sweaters. They do button-down shirts. Noah is another super popular streetwear brand. Brendon Babenzien, who is the founder of that brand, recently disagreed that Noah can be classified as streetwear. He thinks of his clothes as prep.

That’s because button-downs and Shetland sweaters and tweed jackets are like the ABCs of our American clothing menswear language, but they are constantly being recontextualized to mean prep or streetwear, depending on how someone’s styling it. Aimé Leon Dore is basically recontextualization, in my opinion, of Ralph Lauren, and Ralph Lauren is just a recontextualization of Brooks Brothers for different generations and for different demographics.

Globalization and Garments

You’ve been an astute observer of the complexities of international supply chains and the ways they make clothing manufacturing today especially difficult to wrap your mind around. How are garments produced today, and how does that differ from how they were made in the past? What has the globalization of garment production done to the relationships between how clothing is made and how clothing is worn?

To answer that question, you have to understand, again, prior to the popularization of ready-to-wear clothing, most men had clothes made in the home — or by a tailor if they could afford one.

If they were getting a suit made, sometimes it would be made by one person. Other times, it’d be made by two, sometimes three people: the cutter, the person who’s drafting and cutting your pattern; the coat-maker, the person who’s taking those cut pieces and sewing them together; and the trouser-maker, the person who’s doing the same thing but for trousers. Sometimes there’d be an additional person called the finisher, who would be finishing the buttonholes and doing the ironwork and things like that.

That is the original cottage system of how clothes were made. When ready-to-wear appeared and became refined, the system became industrialized. In that old, traditional system of bespoke, you have two main people: the cutter and the tailor. We talked about the cutter, the person cutting and drafting a pattern; the person sewing the pieces together is the tailor.

When it moved to the industrial system, these two roles get split up into many different parts. You have the pattern-maker, who’s the person that’s constructing the architectural blueprint for the pattern. You have the designer, who’s sometimes not even someone who even knows how to sew or draft a pattern. Then you have the people on the sewing line who are sewing these things together.

Even those parts can be broken into components, so you have someone who just does the collar, someone who just does the sleeve, and so on. Then you have the presser, the buttonhole makers, etc. That is a good way to understand the original breakup of how manufacturing through industrialization goes, through the system that Adam Smith had originally written about, specialization over time.

This is not just within clothing, but within [many sectors]. You have these different specializations, where it’s possible these [different jobs] start drifting away, especially with free-trade agreements. For example, the person who spun the yarn — maybe the person is not the farmer — they go to a farmer and buy a bunch of wool, and they bring the wool home and spin the yarn. And then they bring the yarn to their loom and make some fabric, and then they sell that fabric.

Now all of a sudden, you have people like the farmers in Mongolia — they’re growing the cashmere, brushing it off the animal. They sell it to auction houses. The auction houses are auctioning it off to buyers. Those buyers then sell it to spinners. That spinner, for example in cashmere, might be Todd and Duncan in Scotland. Todd and Duncan takes those cashmere fibers from Mongolia, spins it into yarn, and then they create cones of yarn.

These cones are then sold; often they’ll be sold to, let’s say, a mill in Scotland or Italy or sometimes even the United States. That mill will put these cones on machines and they’ll weave fabric. Now they have fabric and will sell that to someone.

That could be anybody. Garment factories in China, Italy, England, the US, Latin America, Bangladesh — a factory will buy the fabric. And then a designer comes to it and says, I want to make this design. Then there are all of these specialized components, these specialized people within that factory. They make the item — import various trims and all of the components that we’re talking about. The buttons, the inner linings, the padding, the shoulder pads — all of these have their own separate supply chains that have drifted off and gone through a similar system.

All this then comes together into a garment that arrives in your hands with a label inside that says “Made in X.” That label is governed by a certain country’s laws. In the United States, in order to say something is made in America, the garment has to be made from start to finish in the US, unless there is some part that just simply cannot be sourced here. To give an example, if you buy a T-shirt and it says “Made in the USA,” under federal law, the fiber has to be grown here, the yarn has to be spun here, the fabric has to be woven here, the garment has to be cut and sewn here. Then if there’s a graphic on it, the graphic has to be applied in the United States for it to carry the “Made in the USA” label.

That’s federal law. The reality is that you are probably not going to get caught if you break that law, because Uncle Sam is not sitting next to you the entire time making sure that you are abiding by the law. Someone has to rat you out for you to get caught. It’s hard to get caught. Essentially, what ends up happening is that some very large companies, like Levi’s and L. L. Bean, do get caught breaking this law. Typically, they have legal teams that advise them to follow the letter [of the law], and if it doesn’t say “Made in China” or “Made in Bangladesh” or whatever, if it’s made in America, it will say “Made in America from imported materials.”

Those big companies are very cautious about getting caught. Although, again, if you Google “FTC [Federal Trade Commission] fines clothing company,” you’ll find a bunch of big companies that will have been charged pretty hefty fines for not following federal law on this.

However, in Italy, for example, it’s common for a garment to be almost entirely made abroad, brought to Italy, and then finished with some process, we’ll say, that is not the majority of the process. And then it gets slapped with a “Made in Italy” label.

Whatever the country’s laws are governing the country-of-origin label, the reality is that there is often a supply chain in the system that is not fully captured by the label. So even if it says something like “Made in China,” the fibers could have been grown in one part of the world, spun into yarn in another, and woven into fabric in another; the design could happen anywhere. That comes to a factory, and all of this comes together for a garment.

Some of these places can have specializations. There’s some debate on why this is. For “connoisseurs” or people who really care about this stuff, Japanese denim tends to be held in a certain high regard because it’s considered more interesting, more unique, more artisanal. There is something about Japanese denim. That could be a result of just regional labor expertise and skill.

Similar to Scottish sweaters or Scottish knitwear.

Another part, some would argue, has to do with something inherent to the region. Again, you always have to take this with a grain of salt because there is some commercial marketing interest in this. But if we are to take companies at their word, Italian mills will tell you that you cannot produce Italian fabric the way they produce it in Italy. Every time you are spinning the yarn and then weaving the fabric, it has to be washed because you have to get rid of the impurities in the fiber for it to be usable in clothing. According to Italians, there’s something about the Italian water that gives it a certain handle.

Some of this about regional specialization possibly has something to do with the climate, water, animals, whatever. On the issue of garment production, once you conceptualize it as: Originally there was a guy who went to his tailor. There was a tailor and cutter in the local area. They worked with local fabric mills that sourced yarns from a local company and got their fibers from local sheep. . . . All of that started to go through the Adam Smith capitalism process of specialization. Then over time, especially with both free-trade agreements and digital technology, a lot of these parts of the industry started to physically drift away, go to other areas of the world. And over time, those areas have also developed certain specializations.

So would you say that’s mainly happened in the last thirty years or so?

We’ve had globalization for centuries, but certainly in the way that we talk about garment manufacturing in the United States, a lot of the offshoring started to happen in the 1990s. Although American clothing companies were already facing pressures in the 1990s — that’s how we ended up getting the fast-fashion system.

People often think of the term “fast fashion” as just meaning cheap clothing. That’s not what it means. Fast fashion is a specific mode of production. Originally you had the cutter and tailor: You as a man would go to your tailor and you’d say, “I need a suit for work. I’m a clerk at this office,” or “I need a suit to go to a summer wedding.” The tailor would give you some fabrics to choose from, and then you’d come out with the thing that you’re supposed to wear. Again, that thing was dictated by time, place, and occasion.

As we move into the industrial period with ready-to-wear clothing and then the breakup of the cutter into designer and patternmaker, who are also working in conjunction with the designer, we now move into a new system of clothing production. A designer sitting somewhere in an office is imagining a collection and they’re thinking, my collection is inspired by the French Riviera, or the American cowboy, or the Italian industrialists, or whatever it is. And they develop this collection that they think men will want to wear. They identify a market — they think twenty-five-year-old finance guy or sixty-year-old working-class guy, whatever it is — and figures out the pattern, the typical body shape.

That person develops this line, creates samples, and brings those samples to a trade show. That’s where we get runway shows or we get trade shows like Pitti Uomo or Magic. They show their samples on models or sometimes just as part of a collection. Then, at that trade show, there are store buyers, and the store buyer says, I love this jacket, those pants, and I think the people that come to my store will want to buy that. I’ll order 100 units, or 500 units, or whatever. Now the designer goes to their factory and says, OK, I need to produce all of these clothes for these orders, and they’ll produce them and then ship them to the store about six months later.

So when you go to a store, the clothes that you can touch and see have gone through a long developmental process. First, there was the factory that made it — that was six months ago. That was when they placed the order. And the development process for that garment, of designing and thinking of that collection, that could have been a year or a year and a half ago.

Which is why the spring/summer collections come out in the fall.

Yeah. When you go to J.Crew and you’re touching a garment, the person who designed that is now already thinking a season and a half out. Like, if you’re touching that garment in October, that person is already thinking about next year’s October collection. That system has a natural lag time to it.

In the 1990s, when we talk about the opening of free trade, American clothing companies were already experiencing pressure from international brands. There were already imports; it just was not [Bill] Clinton levels of offshoring. Those stores started to feel like they needed to figure out a way to be more competitive.

So instead of ordering, say, a hundred of this item and two hundred of that item, they would stock very shallow amounts. They would say, I only want, like, twenty of this item and fifty of that item. Then they would stock the shelves and have an inventory system.

Again, going back to the idea that our clothing styles rest on the shifting tectonic plates of politics, economics, and technology — it required a digital technology system to manage the inventory. When the store saw that it bought fifty red shirts and fifty blue shirts but everybody’s buying the blue shirts and nobody’s really buying the red shirts, the store would have a shallow inventory system. And it could catch it right at the moment that it started to notice the blue shirts are moving really quickly, so [the store would] quickly re-up. That factory would immediately go into production and then ship out those blue shirts so the store could restock very quickly.

This is just-in-time production. This was the innovation of the Japanese production system in the ’70s, right?

Yes, exactly. Just as the Japanese had done this for car manufacturing, American retailers took this for clothing retailing.

Now you’re doing two things. One is that you’re exposing yourself to less risk, because what happens if you buy fifty blue shirts and fifty red shirts, and the blue shirts sell out, but only one person bought a red shirt, and now you’ve got forty-nine pieces that you have to put on sale? You might break even, or you possibly lose money. Now you expose yourself to less risk because you’re stocking shallowly.

The other thing is that you can quickly re-up, and you can respond to trends. Because remember, back in the old system, a designer is thinking of what you want, and then they go into production. You go to the store, and you’re the ultimate judge. It could be, all of a sudden Brad Pitt walks onto the red carpet and he’s wearing a blue shirt. Now everybody wants blue shirts. A designer can’t possibly account for all of these crazy, quick trends.

It was the Americans who actually came up with the just-in-time production system for retail that then gets transported and refined by European companies such as Zara and H&M, which controlled the vertical integration of the system. In the old system, whereas a designer might design a collection and ship a spring/summer collection and a fall/winter collection that then gets moved over time to spring, summer, fall, winter, and sometimes pre-fall, pre-spring. They’re doing more and more drops, but once you get into the fast-fashion system where a company can stock shallowly and they can respond more quickly, they start doing fifteen, twenty, fifty, sixty collections per year.

So if you go to Zara every single week, there’s going to be new items because they’re responding to the fact that Kim Kardashian just posted a photo on Instagram, and then a couple weeks later, they’ll have their version of that in the store. Zara and H&M are also prehistoric at this point. That’s old news.

H&M is what, twenty-five, thirty years old?

Yeah, the new system is Shein and Temu, and they have new stuff every day, by the hour. Computers are constantly figuring out not only what’s selling in their store but what’s selling on the market. If fleece is trending and double riders are trending, all of a sudden they’ll do a fleece double rider. They’re just combining random things.

A double rider, by the way, is a motorcycle jacket, like the Marlon Brando motorcycle jacket.

Yeah. [There are a couple problems with] fast fashion. As long as you understand that fashion is social language and is a way for us to identify with groups and signal our individuality within groups, you then understand what’s wrong with the system. In the previous system, we were dressing according to time, place, and occasion — which was restrictive. It was not great for expression. Then we moved to a system where there are designers and factories that are presenting these collections and ideas, and then a down-market clothier would be like, that sold at Tom Ford. And then a mid-tier clothier copied it, and that sold pretty well. So I, as a low-tier clothier, will copy the mid-tier version and then introduce it, and that would be like two or three years out from when Tom Ford originally introduced it.

Then we move into the system where things move much more quickly, so as soon as Tom Ford debuts it on the runway, you already have the Shein version that’s online. Sometimes the Shein version is available to consumers before the designer version, because the designer version still has to go through the whole factory six-month drop system, whereas the Shein version is like. . . . There was a funny post where a fast-fashion brand posted a photo. Kim Kardashian had worn a sample from a designer, and then hours later, the fast-fashion brand posted their photo, and it said something like, “The devil works hard, but we work harder.”

There’s a human cost to it if you’re the consumer who’s buying through these rapid trends. Whereas in the old system you buy something from a tailor and you’re wearing it for decades, in the new system, you’re constantly trying to keep up with trends. If you’re buying hundreds of garments per year, you can’t spend that much on one garment unless you’re literally Kim Kardashian. Most people have a certain budget. So then the cost of the item has to fall.

When the cost of the item has to fall, certainly you have to cut back on the quality of the materials, but more important, as Marx pointed out, the capitalist can turn a profit by squeezing wages. The capitalist is always trying to squeeze the wage. That’s how you get these really horrible systems where . . . I interviewed a garment worker who worked in a LA sweatshop. She said, for some of these fast-fashion dresses that sell for $50 or so, she gets paid $0.15.

Unbelievable. And that’s in the United States.

That’s in Los Angeles. People are going to be like, “How’s that possible? We have minimum wage laws.” Garment factories work on a piece-rate system where the garment worker is paid per operation, not per amount of time worked. Many people will be familiar with this. For example, I’m a freelance writer, so someone will pay me a certain amount to write an essay. I could spend one thousand hours on that essay, I could spend an hour on that essay, but I’m getting paid by the essay.

It’s somewhat similar in a garment factory in that you get paid for sewing the sleeve, the collar, and so on. When I was interviewing this garment worker, there was a moment when I choked up; I couldn’t take it anymore. I asked her how much she takes home per week. From what I remember, it was around $300 per week. It’s very, very low — she worked seven days a week, twelve-hour days. And I said, how do you pay rent in Los Angeles? And she said she lives in a two-bedroom apartment with seven people. There are two people in each bedroom, two people in the living room, and she sleeps on the floor in the kitchen.

I’m sure your readers know Mike Davis’s City of Quartz, an incredible book about the history of Los Angeles. It talks about the surveillance system that separates different classes in Los Angeles, which is indicative of not only America but also how the world is structured. The garment district where this woman works and then goes home and sleeps on the floor of a bustling kitchen . . . just a few blocks away. The clothes are being presented in this glamorous, aspirational way. But what actually makes that price possible is the toil that you don’t see where that woman works just blocks ahead.

And that system exists, one, because of the piece-rate system. But two, the physical separation of your ability to see this is enforced by the police, who push homeless people away so that they don’t bum you out when you go shopping. This happens in every city. Instead of solving homelessness, we just don’t want to see the people: you just can’t loiter here. You can’t sleep on the bench. You can’t sleep here; you can’t sleep there. But the homeless person is going to be homeless whether you see them or not.

In this specific LA geographical area, the garment district, where you can physically go and see these sweatshops — it’s like a ten-minute drive — and go to the shopping center, and that center is gleaming and beautiful. All of the clothes are presented in this beautiful way. It’s enforced by all of the systems that Mike Davis wrote about in City of Quartz: the cameras, the police, all of this stuff to make sure that you don’t see the ugliness that will bum you out.

One of the things that is so important to think about when we talk about the clothing industry and about garment manufacture, is that from the Industrial Revolution on, the garment industry has been the center of not only workplace abuses — you’re right to point out that Marx’s whole concept of surplus value imagines a Lancashire mill owner — but also, there have been these epic showdowns between workers and management that have gone on throughout the garment industry: whether you think about the early twentieth century in New York, the Farah strike in El Paso in the 1970s, the 1982 garment workers’ strike in Chinatown in New York, or labor organizing in Bangladesh post–Rana Plaza collapse. The garment industry is where the rubber meets the road often in terms of innovation, new technologies, and worker exploitation but also of workers learning how to organize against those new technologies.

We talked earlier about this offshoring system. There’s a lot of discussion now about bringing garment manufacturing back. I personally think that instead of trying to reshore all of garment manufacturing, we should as a country focus on the high-end parts that we can export onto the global market.

People say, why can’t we make stuff as we did in the 1960s? Two things. One is that whenever we talk about American garment manufacturing in the 1940s, ’50s, ’60s, and so forth, we have to understand that there were massive government scaffolding programs that trained people how to sew. There were the 4-H programs. The USDA [Department of Agriculture] had a Bureau of Home Economics that taught people how to sew. And then there were obviously home-economics programs teaching women how to sew, because this was a time when labor was divided by gender.

It’s not that people just came out of high school with nothing and then filled garment factories. These people knew how to sew. And over the course of the twentieth century, many of those programs started to recede — reasonably, because America was moving toward a kind of postindustrial economy. When I was going to school, we didn’t really have home-economics programs. We had typing classes, keyboard classes, because they were training us for email jobs. That’s where we all thought the economy was going and where the economy has gone.