The Curious Case of Steve Bannon’s Tactics

Self-described Leninist Steve Bannon recognized that online platforms and movement tactics can be turned into political weapons. His success shows how tactics developed for solidarity can be twisted into resentment.

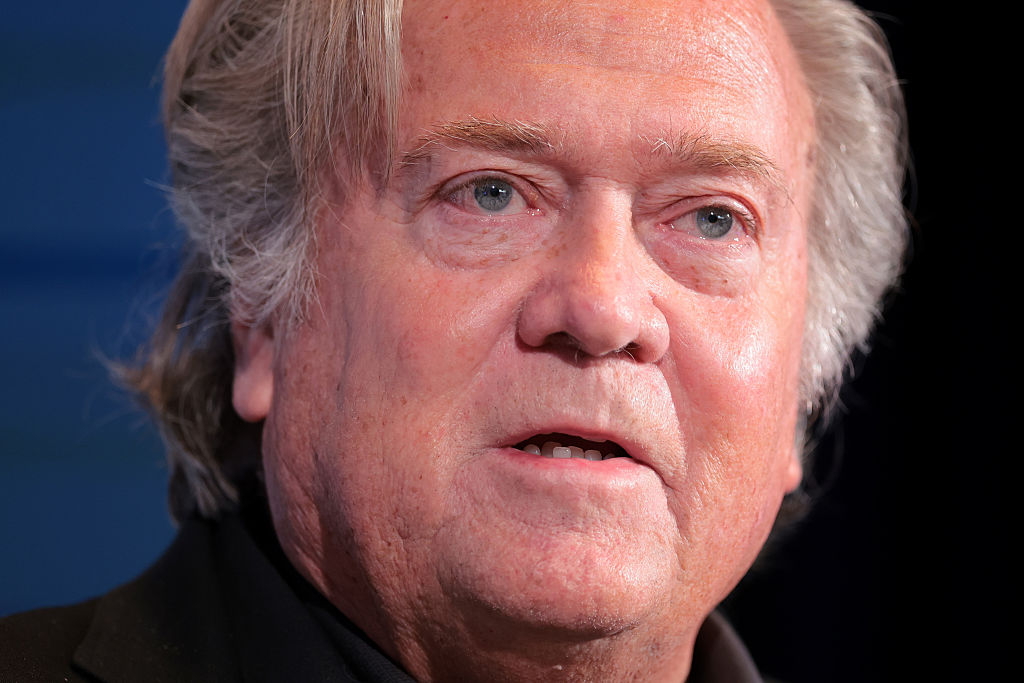

While the Left organized deliberative meetings, Steve Bannon flooded communication channels with what he termed “shit.” (Kayla Bartkowski / Getty Images)

In August 2012, Steve Bannon sat in a Santa Monica office watching World of Warcraft players coordinate raids against impossible odds. The gamers never met in person. They didn’t share political views. Many couldn’t articulate why they kept logging on, night after night, to fight battles that existed only in code. But they fought with a collective intensity that organizers on the Left have struggled to mobilize.

Bannon grasped what these organizers had missed: that coordination through new media mechanics could sometimes mobilize people more effectively than ideological argument, that shared tasks could create solidarity without requiring shared beliefs. But coordination is never empty of content, never purely technical. These systems don’t replace ideology. Instead, they become vessels for it — channels through which particular visions of the future flow. The question isn’t whether coordination mechanisms carry political meaning but which meaning they carry, whose futures they enable, and what worlds they help construct.

Bannon’s discovery in how to shape the world occurred years earlier in Hong Kong, where he operated a company that employed Chinese workers to play World of Warcraft in continuous shifts, farming virtual gold to sell to American gamers who preferred purchasing advancement to achieving it through gameplay. When players organized systematic campaigns to destroy his business — coordinating boycotts across multiple servers, flooding message boards with economic analyses of how gold farming undermined game ecosystems, maintaining sustained resistance without formal leadership structures — Bannon recognized political potential rather than commercial failure in their passionate coordination.

“These guys,” he would tell Bloomberg journalist Joshua Green years later, “these rootless white males, had monster power.”

Move Fast and Break Things

While Bannon analyzed digital coordination mechanisms, the American left perfected methodologies that prioritized process over outcomes. Endless consensus meetings allowed individual participants to block collective decisions, which meant substantive action remained perpetually deferred. Movements often achieved very little beyond maintaining food distribution networks and lending libraries, until seasonal weather changes made encampments untenable and participants returned home. Movements like Occupy Wall Street remained trapped in consensus procedures that could debate for hours without reaching decisions, even as they simultaneously built impressive mutual aid infrastructure — food distribution, libraries, medical tents — that would later serve as blueprints for COVID-19-era organizing and dual power experiments.

Decades of justified critiques of authoritarian socialist movements had produced retreat into what Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams call “folk politics.” This meant a methodological obsession with local organizing, consensus processes, and authentic face-to-face interaction, which treats technological mediation not as a terrain to be contested but a corrupting influence — even though it has become a prominent battleground for contemporary politics.

Suspicion of scale, aversion to hierarchy, and discomfort with technology gave rise to a strategic orientation that abandoned precisely the capacities contemporary capitalism had entrenched and that far-right populist movements later appropriated. These included abstraction, mediation, and the ability to coordinate across distance. Bannon grasped what folk-political methodology systematically refused to acknowledge: that twenty-first-century political coordination often operates through technological platforms rather than physical assemblies and demands digital literacy and algorithmic strategy rather than consensus processes designed for smaller-scale interaction.

The $60 million Goldman Sachs investment in his gaming company eventually collapsed through coordinated player resistance and legal challenges, but Bannon retained insights that would prove more valuable than financial returns. When he assumed control of Breitbart News in 2012, he transformed it into what he described as “a killing machine” — a metaphor that indicated a systematic approach rather than mere aggression. Breitbart functioned not as a traditional news organization but as a recruitment and coordination platform where every headline served emotional mobilization rather than informational accuracy; every article was optimized for viral circulation through Facebook’s algorithm; every comment section constructed community through shared resentment rather than common purpose.

His recruitment of Milo Yiannopoulos represented strategic bridge-building. As Bannon explained it, he believed Milo could connect “these rootless, disaffected white gamers” with “the Breitbart world of populist politics.” When Gamergate erupted in 2014, Breitbart provided extensive coverage while Yiannopoulos embedded directly within harassment coordination networks, demonstrating how gaming coordination mechanics could be weaponized to target women in the industry while establishing an operational template for the political campaigns that would follow.

Bannon’s operational innovation was in temporal manipulation. He understood that speed itself could be a weapon. If you moved fast enough, you could make information feel true before anyone had a chance to check it. While traditional media organizations maintained fact-checking protocols, Breitbart published content designed for immediate emotional impact. Liberal commentators developed careful explanations, but Breitbart deployed rapid-fire attacks. While the Left organized deliberative meetings, Bannon flooded communication channels with what he termed “shit,” recognizing that in information warfare, volume beats accuracy, and pace overwhelms thoughtful response.

Applause by Snap vs. Power by Seizure

The 2016 election demonstrated how well Bannon’s methods fit the media environment that had already taken shape. Scandals and shocks piled up — the steady release of WikiLeaks documents, the spread of conspiracy theories, and the Access Hollywood tape revelation — but none stuck around for long. Each became absorbed within accelerating news cycles, preventing any one single controversy from dominating public attention. Traditional media never had time to catch up, and Hillary Clinton’s deep policy resume couldn’t compete with the infrastructure of speed and distraction that Bannon helped exploit.

The Cambridge Analytica revelations later confirmed what should have been obvious to anyone analyzing platform capitalism’s political implications: Bannon had weaponized Facebook’s data collection systems. He used them for microtargeted propaganda delivery and exploited algorithmic recommendation engines to tilt the flow of political information. This wasn’t some freakish corruption of democracy but the logical extension of a system where the same infrastructure that sells sneakers and potato chips is also the terrain on which political power is contested.

But the method had limits. The Trump White House needed durable governance, not just disruption. Bannon was gone after seven months, admitting to the Weekly Standard that the Trump presidency he had helped construct was “over.” Coordination tactics that worked in campaigns and outrage cycles proved useless when the task was running institutions.

Back at Breitbart, he immediately declared war on the Republican establishment. His influence peaked with Roy Moore’s Senate campaign in Alabama, but Moore’s defeat by Democrat Doug Jones showed the ceiling: gaming mechanics optimized for short-term intensity could not sustain the longer timelines and institutional requirements that democratic participation demands.

Senate Republicans immediately blamed Bannon for the defeat, though concentrating blame on individual failure obscures the larger point: revolutionary techniques function regardless of their political content. Consider the specific organizing methods that the Left pioneered and then abandoned: Indymedia’s decentralized network of 142 autonomous media centers that coordinated global anti-capitalist protests from 1999 to 2006, creating what Todd Wolfson called “the Cyber Left” with its horizontalist, leaderless structures inspired by the Zapatistas.

These same organizational principles that once powered the Seattle World Trade Organization protests now animate Bannon’s precinct strategy, which has recruited over 8,500 new Republican precinct officers across forty-one counties since he began promoting it on his War Room podcast in February 2021. Where Indymedia once used open publishing and distributed coordination to mobilize rapid response protests, Bannon’s War Room now broadcasts six days a week to coordinate what he calls “MAGA shock troops.” These “troops” flood local GOP committees, a fact made clear when Texas precinct chairs reported callers asking about “precinct committeemen” — the term Bannon uses on-air — rather than the correct local term “precinct chair.” The infrastructure that facilitated the Battle of Seattle’s spontaneous affinity groups and bicycle courier networks has been repurposed for what Bannon explicitly calls taking over the Republican Party “village by village, precinct by precinct.”

The Left’s horror at Bannon’s success conceals a harder truth. He won elections where progressive movements produced beautiful failures. He seized institutional power while we practiced democratic procedures in marginal spaces. The political conversation he drove at scale unfolded while our organizing remained confined to the local.

This asymmetry demands analysis rather than moral denunciation. It requires the acknowledgment that twenty-first-century politics operates through infrastructural control rather than just ideological persuasion. It moves at speeds that consensus-based decision-making cannot match, across geographical scales that face-to-face organizing often cannot reach.

The Path From Shitposting to Solidarity

The strategic implication is neither to imitate Bannon’s nihilistic methods nor to retreat into folk-political purity but to develop what might be called “infrastructural socialism”: building digital platforms that serve human flourishing rather than domination, creating coordination systems that enable solidarity rather than resentment, and achieving organizational velocity without sacrificing principled commitment to emancipatory transformation. This approach finds its philosophical foundation in what Ernst Bloch called the “principle of hope” — disciplined optimism toward futures not yet conscious, set against Bannon’s “Fourth Turning” mythology, which promises meaning only through eternal cycles of crisis, destruction, and renewal.

Bloch’s three-volume work traced utopian impulses across art, literature, religion, and philosophy. He argued that hope represents not passive waiting but active engagement with possibilities already latent in the present, distinguishing between abstract utopia that escapes from reality and concrete utopia, which emerges from reality’s contradictions. Where Bannon’s temporal framework naturalizes catastrophe as necessary transition, Bloch’s framework politicizes hope as educated militancy toward open futures — sustaining orientation without prescribing outcomes, precisely what Bannon’s fatalism forecloses.

Leszek Kolakowski, expelled from the Polish Communist Party after defending the 1956 uprising, understood something essential about revolutionary consciousness while writing from exile in Oxford. He argued that impossible goals must be articulated precisely because they remain impossible, that revolutionary movements require what he called “mental counterparts” to material struggle — not as religious mystification, but the symbolic architecture that sustains hope through inevitable defeats. As Kolakowski recognized, the Left needs a utopian vision precisely because it seems impossible.

Michael Brooks exemplified what operational socialism might mean in digital conditions, combining rigorous political analysis with strategic media intervention through the Majority Report. Brooks demonstrated how left media infrastructure could match right-wing operations without adopting their methods. He understood that socialism must be cosmopolitan rather than nationalist, spiritual as well as material, joyful as well as militant. He refused the false choice between serious analysis and popular accessibility while showing how to build audiences without algorithmic manipulation, create community without manufactured outrage, and maintain hope without naive optimism regarding capitalism’s structural constraints.

Platforms Are Neutral Until They’re Not

The COVID-19 mutual aid networks provided additional demonstration of how digital platforms can sustain solidarity: they maintained human connection, achieved coordination across geographical distance through federation rather than centralization, and built collective power through solidarity rather than domination. These networks showed how technological infrastructure can serve cooperative rather than competitive ends while making Peter Kropotkin’s insights regarding mutual aid as evolutionary force operational through contemporary organizational methods. Kropotkin argues that cooperation constitutes as powerful a force as competition within natural development. But recognizing mutual aid’s evolutionary significance requires making cooperation operational through actual institutions, not just apprecaiting it in theory.

The coordination patterns Bannon identified continue to operate through infrastructures that now operate independently of him. Technological systems generate political effects independently of their creators’ intentions: TikTok algorithms produce political engagement through participation rather than persuasion; Discord servers coordinate collective action among users who share aesthetic sensibilities without requiring ideological agreement; and streaming platforms create synthetic communities with genuine emotional stakes, where parasocial ties often command more loyalty than traditional political-party membership. In coffee shops where young organizers coordinate mutual aid through GroupMe threads, employing distributed coordination principles that Bannon discovered within World of Warcraft guild structures, different political possibilities become visible through identical technological means applied toward emancipatory rather than reactionary purposes.

These organizers may have never heard of Steve Bannon, but they grasp intuitively what his career demonstrated: sustainable political power emerges from participation in properly structured systems rather than from ideological conversion or charismatic leadership. It requires infrastructure that enables coordination, not rhetoric that demands agreement. Bannon’s offer of the Fourth Turning sees history as eternal repetition — crisis and renewal continuing indefinitely through cyclical necessity that naturalizes catastrophe while promising restoration of imagined past conditions. The Left can offer a different temporal vision: not a circle but a spiral. Development that learns from the past without repeating it, movement through time that pushes beyond recurrence, transformation that opens new possibilities instead of restoring previous arrangements.

This means not making America great again but making America what it never was — a society where technological infrastructure serves human flourishing rather than domination. Coordination could enable liberation rather than control and the principle of hope could guide development toward open futures rather than closed cycles.

The infrastructure remains available, but infrastructure alone determines nothing. Coodination systems aren’t ideologically neutral; they’re vessels waiting to be filled, capable of carrying either emancipatory or reactionary visions into practice. The methods survive their originator’s particular purposes, but without meaning they remain empty technique. The real question isn’t whether these tools will be used but what they’ll be used for: hope or pessimism regarding humanity’s potential for creating unprecedented forms of collective life.