George W. Bush Lives on in Donald Trump’s Migrant Policies

Twenty-four years ago, the “war on terror” led to a sweeping curtailment of immigrants’ rights that swept up green card holders as well as citizens. Its echoes are alive and well today in Donald Trump’s attacks on immigrants.

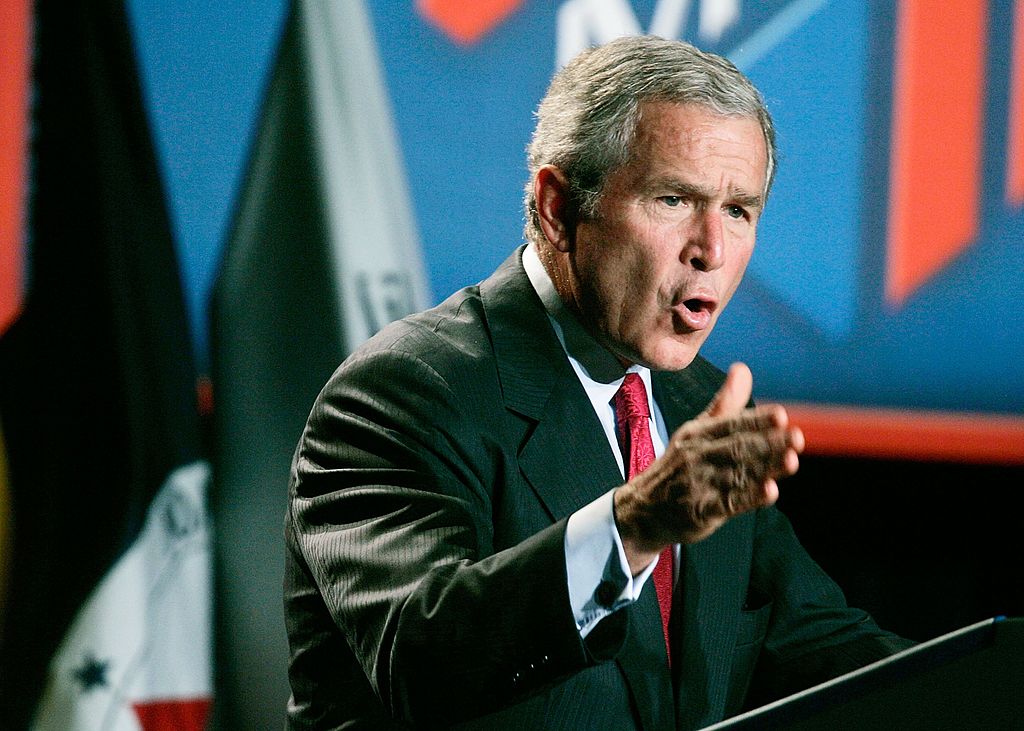

George W. Bush speaking to the Military Officers Association of America about the war on terrorism and the situation in Iraq on September 5, 2006, in Washington DC. (Mark Wilson / Getty Images)

Barely two months into the second Donald Trump presidency, the campaign promise of “mass deportation” of undocumented immigrants who are violent criminals seems to have become a policy of simply kicking out any immigrants deemed undesirable by the White House. The Trump administration is currently trying to deport several green card holders for taking part in antiwar protests, revoked several visas over their holders’ political views, and refused a visa holder entry for content contained on his phone, including private messages criticizing Trump policies.

It’s easy to see why this has already been compared to past Red Scares and episodes like the Palmer Raids. But there’s also a more recent era we can point to: George W. Bush’s “war on terror” a quarter of a century ago.

We usually think of Bush’s war on terror policies as a series of foolish, destructive, and often lawless invasions and foreign policy decisions. But it was also a sweeping curtailment of the rights of US immigrants that saw noncitizens — and sometimes, even citizens — of the United States questioned, rounded up, deported, and in some cases detained for as long as months, often on false suspicion.

Not So Permanent Residents

Shortly after Bush made a now-famous speech insisting the United States was not at war with Islam, his administration began rounding up roughly 1,200 mostly Arab and Muslim immigrants, most of whom were charged and deported for minor immigration infractions. Some were told to simply report themselves or at most come in for simple questioning by immigration officials only to be arrested, while others were arrested for no crime other than being Muslim or Arab in a climate of fear and hysteria.

Take Ansar Mahmood, a legal permanent resident who was detained for, at first, four weeks, then spent three years in prison before being expelled from the United States and barred from ever coming back — all for taking a picture.

About a month after the September 11 attacks, Mahmood, a pizza delivery driver who had won the green card lottery in 1999, drove up to the highest point in Hudson, New York, to have his picture taken to send back to his family in Pakistan. But that lookout happened to include the town’s main water treatment plant, leading guards to call the police on him, and the opening of a federal terrorism investigation which found nothing — except that Mahmood had helped a Pakistani couple on expired visas get a house and car, leading the federal government to charge him with the felony of harboring undocumented immigrants.

Mahmood denied and would forever deny that he had known their visas were expired, but while being interrogated, he signed a statement that he did. Despite local activists rallying around him, and a yearslong legal battle, Mahmood was deported, purposefully plonked on a commercial flight to Pakistan before the Americans who had befriended him and taken up his cause could even say goodbye. He could not even be saved by lobbying from Sen. Chuck Schumer, who declared his deportation “a disgrace,” said bluntly that “this is not a terrorism case,” and called Mahmood “the kind of person America should embrace” — in stark contrast to Schumer’s equivocation today over the Mahmoud Khalil case. For his part, Mahmood a decade later only had positive feelings about the United States and its people.

There was also the case of Muhammad Bachir, who had left a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon twenty-three years earlier to become a permanent resident, getting married, having kids, and holding several jobs — only to end up having, as he put it, “lost everything” at the hands of the Bush administration, including his job, house, and family. After a hospitalization led him to miss a June 2001 interview with the Immigration and Naturalization Service over some immigration violations, months went by with nothing before Bachir was arrested and detained for missing the appointment.

Agents accused Bachir of being a terrorist and a member of the Palestine Liberation Organization and drew up criminal charges that were all eventually dropped, before arresting him again and holding him for eighteen months, shipping him to seventeen different detention facilities all across the country. According to Bachir, agents made comments to him that indicated he was being punished for having publicized his case to the press and human rights groups, and at one point admitted they were aware he really had missed his INS interview after being hospitalized. Bachir was eventually freed and left to find a way back to California from New York with only $23 in his pocket.

Or look at Osama Awadallah, another permanent resident who fought a similar legal battle after being arrested and detained ten days following the attacks, because authorities found a scrap of paper with his name and phone number in a car owned by one of the hijackers. Awadallah was at no point formally accused of being involved in the attacks or knowing about them in advance. He had only known the hijackers incidentally. Yet agents seized him (unlawfully, a court would later conclude), interrogated him for hours while refusing to let him talk to a lawyer, called him a terrorist, and later charged him with perjury, for which he was acquitted.

These are just a few cases where permanent residents suffered startling violations of their basic rights. But it wasn’t just green card holders — US citizens, too, suffered both directly and indirectly.

Citizens Not Spared

One citizen — Mohammed “Freddy” Alfaorri, a San Bernardino ice cream truck driver from Jordan who became an American citizen in 2002 — was arrested and taken away to an immigration facility not once, but twice, the second time with guns drawn and after agents had already apologized to him and acknowledged he was a citizen. For fourteen days, Alfaorri had no access to a lawyer, had his naturalization card taken by authorities, and agents badgered him to “admit” he wasn’t really documented — before suddenly telling him he was free and leaving him in the middle of Los Angeles with little money, while his wife was hospitalized due to a stroke. Authorities wouldn’t even give him his naturalization card back until he got a lawyer.

Another citizen, a sixty-five-year-old man of Palestinian descent named Fathi Mustafa, was detained for ten days on a trip back from Mexico because he and his son’s passports had an extra layer of laminate that immigration officials considered suspicious. Mustafa was made to wear a leg monitor after he was released, inviting strange looks from people in his small Florida town, while his son, who had a previous arrest, was held for two months and said it cost him tens of thousands of dollars in business.

Still another citizen, military recruit Tiffany Hughes, was searched and detained with her Yemeni husband at an army base, at various points being told she could not wear a hijab and that she should not “let people know that you’re Muslim,” before being followed around at the base for nearly two weeks no matter where she went and eventually being pressured to take an honorable discharge. Her noncitizen husband was kept mostly in solitary confinement for fifty-two days, during which time investigators made wild accusations that he was beating his wife and lied that she had written a statement alleging as much.

As with green card holders in the post-9/11 period, these are just a few stories out of many where citizens were swept up or saw their rights undermined.

A US citizen was among the nine Egyptians arrested in Indiana on October 11 on the basis that they were material witnesses to the September 11 attacks, kept for days without being allowed a phone call or access to attorneys, before being released. Numerous other citizens reported being stopped, interrogated, and even detained upon coming back into the country, including one man who had a passport control officer question him aggressively about his religious faith, whether he was pro-Palestine, and if that meant he supported Hamas, before throwing his passport back at him, forcing him to pick it up off the floor. Another was stopped and repeatedly asked for his green card despite being a citizen.

Of course, those treated the harshest were regular visa holders: the Egyptian man forced to leave the country after being arrested over suspicion for studying at the same aeronautical university as one of the hijackers; the young Iranian man put on a national security watchlist then arrested for simply receiving a terroristic email that he voluntarily reported to the police; another Iranian citizen stopped for speeding and subsequently detained for one hundred and twenty days, thirty-five of them in isolation; the Egyptian antiques dealer held in solitary without charges for so long he contemplated killing himself, all because he made flight reservations at the same computer terminal and around the same time as one of the hijackers.

As the New York Times put it, “violations that before Sept. 11 would probably have been ignored or resolved with paperwork” — even being in the country after a visa expired could be remedied with a fine, a report from the California state senate noted — were suddenly used to put people in prison for sometimes months. The FBI was empowered to arrest people for immigration infractions that were civil violations, not criminal ones, and as part of the Bush administration’s Alien Absconder Apprehension Initiative, which prioritized immigrants from countries with an al-Qaeda presence, no violation was too small to justify expelling someone, even if it was the result of a bureaucratic mishap on the government’s end.

Family ties didn’t matter. One US citizen woman was left to deal with illness and struggling to support her three kids all alone after her Jamaican immigrant husband was deported. A US citizen man and his nine-year-old twins were left without a wife and mother when an Indonesian woman was expelled. A German woman married to a citizen and given faulty assurance by an immigration official that she could take their new baby to see her family in Europe was detained and ordered out of the country.

The Start of a Dark Road

The Trump administration is going much further than Bush’s crackdown, asserting the right to, among other things, unilaterally strip permanent residents of their green cards by fiat and deport migrants without due process to be imprisoned in third countries with dismal human rights records. Unlike the early 2000s, there is no deadly terrorist attack on US soil that the Trump administration is pointing to to justify this crackdown.

Still, it’s easy to see how these early Bush-era actions — a combination of paranoia over terrorism and anti-immigrant animus — paved the way for what is now happening. The question is, if what we see today is the end result of what Bush started, where will Trump’s actions today take the country years from now?