The Corporate Takeover of Soccer Is Ruining the World’s Most Popular Game

Manchester City is the hot favorite to win tonight’s Champions League final with the best team that an oil-rich autocracy can buy. It’s the latest stage in a long-term process that has converted the people’s game into a plaything of wealthy elites.

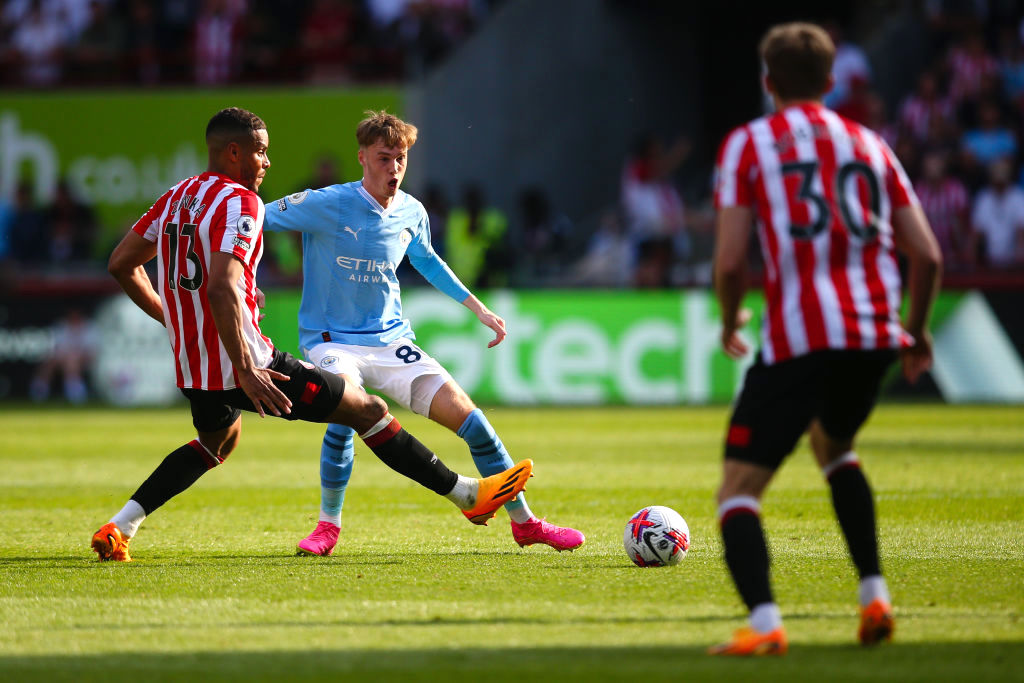

The Premier League match between Brentford FC and Manchester City at Gtech Community Stadium on May 28, 2023 in Brentford, England. (Craig Mercer / MB Media / Getty Images)

- Interview by

- Daniel Finn

Manchester City have just won their fifth Premier League title in six seasons, the culmination of a lavishly funded project to boost the prestige of Abu Dhabi’s ruling family. The Saudi monarchy has bought their domestic rivals Newcastle United and the rulers of Qatar own Paris Saint-Germain.

The financial gulf between the wealthiest clubs and their rivals is wider than ever before, depriving many national leagues of any element of surprise. But members of the self-perpetuating oligarchy at the top of the game are still looking for ways to strengthen their economic advantage. How did a sport deeply rooted in working-class communities become a multibillion-dollar industry where financial doping is the norm, and is there anything that can be done to reverse the process?

We spoke to Jonathan Wilson, a football columnist for the Guardian and the Observer, about the current state of the football industry. His books include Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Football Tactics and Two Brothers: The Life and Times of Bobby and Jackie Charlton. The following is an edited transcript from Jacobin Radio’s Long Reads podcast. You can listen to the interview here.

What do we know today about the circumstances in which Qatar won the right to host the World Cup, and how does it relate to the wider FIFA corruption scandal?

That’s a massive question. What we know is that of the twenty-two members of the executive committee of FIFA who made the decision, sixteen have either been convicted of corruption offenses or credibly accused of corruption. I don’t think there’s any direct evidence against Qatar or indeed Russia — the two hosting decisions were made at the same time — but certainly the body making those decisions has been shown to be flawed.

There were all the arrests in Zurich in 2015, when the FBI got involved. This is one of the problems with football corruption: because it goes cross-border, it’s very hard for anybody to have the authority to take proper action. I think what they actually got them on was fraud over some TV deals in South America: some of the interactions that were questionable were carried out in dollars and that gave the US authorities the right to intervene. It may not be coincidental that the US is hosting the next World Cup in conjunction with Mexico and Canada.

That led to the downfall of Sepp Blatter. I personally don’t find Blatter as objectionable as a lot of people do. It’s very easy to think that FIFA’s corruption was embodied in him. It’s important to stress he’s never been convicted of any corruption, although I think he absolutely did pay himself an enormous salary and very generous expenses.

He was instrumental during the 1970s in helping João Havelange topple Stanley Rous in the presidential election of 1974, which is what led to FIFA’s modern age of corporatism and the corruption that has accompanied that. I think it’s probably fair to say that at some level, he had the best interests of football at heart. He genuinely was an evangelist for football. He believed that FIFA had a chance of winning the Nobel Peace Prize for taking the World Cup to South Africa in 2010.

He had wanted to take it to South Africa four years earlier in 2006. There was some very dodgy stuff going on that resulted in the 2006 tournament going to Germany. A delegate from New Zealand who would have voted for South Africa disappeared the night before the vote and went back to New Zealand.

It was never explained why he did that. If he had stayed, the vote would have been 12–12 and Blatter would have given his casting vote to South Africa. Instead, it was 12–11 in Germany’s favor. That’s never been properly investigated.

Blatter did take the tournament to South Africa in 2010. I don’t think it was a great World Cup, but the idea behind it was laudable. To an extent, Blatter was a realist. He thought that when you have enormous global corporations that essentially exist beyond the reach of any one authority, a certain amount of corruption is inevitable.

What Blatter did was keep an eye on that corruption and expose it when it was politically useful for him, as in the case of Mohammed bin Hammam, the Qatari who stood against him in the 2011 FIFA presidential election. He showed that bin Hamman had made payments to the Caribbean football union. He could take out opponents that way.

He didn’t crack down on corruption, but rather used it to his own ends. Whether that makes him personally corrupt is a slightly different issue. But he was toppled in the wake of the Zurich arrests in 2015. You then had a very strange campaign against Michel Platini, who was the obvious person to succeed Blatter.

Platini had been involved in the Qatar business in a direct way as the president of UEFA [Union of European Football Associations]. It looked as if he and the other two UEFA delegates would vote for the US to be host nation in 2022. Nine days before the vote, he went to a meeting at the Élysée Palace with Nicolas Sarkozy, the French president, and the son of the emir of Qatar, who is now the emir himself. After that meeting, he and the UEFA delegates mysteriously switched their votes to Qatar, and there was then a big order placed by the Qatari government for French fighter jets. Make of that what you will.

In any case, Platini was seen as president-elect after Blatter, if you will. There was then an allegation made that he had taken two million dollars or Swiss francs in an illegal payment from Blatter. The evidence was always quite flimsy, and they were both exonerated earlier this year, but it was enough to end Platini’s political career in the world of football.

He was replaced by Gianni Infantino, the current FIFA president, who has shut down various ethics commissions. Infantino seems quite happy bantering on the world stage with Vladimir Putin and Mohammed bin Salman, and he lives in Qatar, which is also an interesting development.

Last summer, English clubs spent well over €2 billion on transfer fees — more than the next four European leagues put together. Do you think that the architects of the Premier League in the early 1990s had any idea that it would prove to be so successful in global commercial terms?

I’m sure they hoped it would be. It was part of a more general movement in football at the time. Silvio Berlusconi had bought AC Milan in 1986 and rescued them from probable bankruptcy. He gained popularity from that, and it helped launch his political career.

In the 1987–88 season, the Italian champions Napoli played Real Madrid in the first round of the European Cup, which in those days was a straight knockout competition. Berlusconi said this was crazy, because you had two of the biggest TV markets, Italy and Spain, playing against each other: whoever lost was out and you would have lost all that revenue. He said it was a crazy way to organize the competition.

Berlusconi didn’t want his team to win the Italian league and find themselves playing against the Spanish champions or the German champions in the first round. He was very much the leader of a move toward what became the Champions League. The first season of the Champions League, 1992–93, was also the first season of the Premier League.

There was a realization across Europe in the 1980s that the commercial potential of football wasn’t being exploited as much as it could be. In the specific case of England, you had the ban on English clubs playing in Europe that had been imposed after the death of thirty-nine Juventus fans at Heysel stadium in Brussels when their club was playing Liverpool. English clubs were banned from European competitions for five years and lost a lot of revenue and exposure as a result.

Trying to obtain more revenue from domestic TV rights was not so much a bid for world domination as a way of staving off financial crisis. But they went on to market it brilliantly. Whatever you think of its founding principles, the Premier League has run itself better than any other league in the world. The result is that thirty years on, it is absolutely dominant in financial terms.

How important was the purchase of Chelsea by Roman Abramovich in shaping the economic development of English football?

It was hugely important because previously, you always had to do well on the pitch to generate money. Obviously when you generate money, you can buy better players and employ better managers, and you’re then more likely to be successful and generate more revenue in turn.

There had been a recognition that this was the case from the early days of the Football League in England, so there was a general levy of 4 percent of a club’s income that was then divided among all ninety-two league clubs. Twenty-five percent of gate receipts from ticket sales at matches went to the away club. As a result, even though you had an advantage if you had a big stadium, it wasn’t that much of an advantage.

It was only when the TV rights revolution began that you started to have self-perpetuating elites. The term “super club,” which is now bandied about quite freely, first appeared in the early ’70s. There was a recognition that the marketplace had changed with the launch of Match of the Day on the BBC in 1964. You could be a Manchester United fan without having to live near Old Trafford, since you could just watch them play on TV on a Saturday night.

That changed the parameters. In 1981, the English football authorities scrapped the protocol according to which the home club had to give a percentage of gate receipts to the away club. That allowed the big clubs to become bigger — an effect that was magnified after the coming of the Premier League. But even during the first decade of the Premier League, you still had to win games to make money.

Then Abramovich came along and suddenly a club’s wealth was not contingent on its performances. It decoupled success on the pitch from wealth: you could have money just because you had a megarich owner. Of course, this had sometimes happened in the past when a local businessman got involved. Jack Walker, for example, spent a lot of money supporting his local team Blackburn, who went on to win the league in 1994–95.

But the sums involved in those cases were much smaller than what Abramovich was now putting in. In the summer of Abramovich’s first year as owner, Chelsea spent more than the next nine clubs, I think, put together. They weren’t far off that in his second summer, either. It was an enormous investment from an external agent of a kind we’d never seen before.

I had just started out as a journalist at the time, and I think we were pretty naive about it. We just thought, “Oh, it’s an amazing amount of money — this is all very exciting, all these players are arriving.” Alongside that, there was a slight feeling of distaste, wondering how moral it was that a very rich man could come along and break up the existing structures. I don’t think we really had any notion of what we now call “sportswashing” — of the reasons why Abramovich might be investing.

It was only nine or ten years later that we really began to interrogate the question of why he was doing it. We had bought the line that he watched the Champions League match in 2003 where Manchester United beat Real Madrid 4:3 and thought “I love this game — I must buy a slice of it for myself.”

If we looked further, the sense was that he was protecting his own position against Putin by making himself a figure who was well known in the West. Perhaps there really was an element of that because Abramovich subsequently took Israeli citizenship, which you could argue has given him certain escape routes. I don’t think it occurred to anybody to ask if this was part of a wider phenomenon of Russian money inveigling itself into West European society.

But in terms of the impact on football, the obvious comparison is to Arsenal. Around the same time, they had begun the process of moving away from Highbury, their traditional home, which had quite a small capacity and very limited corporate facilities. They realized that if they wanted to challenge Manchester United, they needed their own version of Old Trafford, which at the time was state of the art, with amazing commercial possibilities around it.

Arsenal thus began the process of moving to the Emirates stadium, but it came at an enormous cost. The interest repayments on the loan impacted their ability to pay transfer fees and wages for a long time, even after they moved into the new stadium. By the time that stadium was built, the idea of needing to generate your own revenue was already old hat: revenue had to come from a sugar daddy from abroad. Abramovich began that process of decoupling wealth in football from performance on the pitch or the ability to drag fans through the gate.

The Champions League has clearly widened the gulf between big clubs and small clubs and between big leagues and small leagues across the whole of Europe. Was that always the intention behind it, or is it a case of unintended and unforeseen consequences?

I think it’s very difficult to say. Clearly the fundamental urge was greed, with the big clubs saying we have to make more money. Perhaps there was an unwillingness or an inability to recognize that European football was an enormous ecosystem and that once you started damaging parts of it, that would have ramifications elsewhere. It was totally foreseeable, but I don’t think they did foresee it, if that makes sense.

Some people did, to be fair. Particularly with the Premier League, there was a lot of opposition to it in the early days, with people pointing out that this process of enriching the rich at the expense of the poor was inevitable. But that was never fully communicated to fans, and you didn’t get the same kind of backlash against it that you later had against the proposal for a European Super League.

I think it was an inevitable consequence, and it’s very difficult to put things right once that process has begun. There have been various tweaks made to the Champions League structure to try and encourage clubs from outside the big five leagues. But that brings problems of its own.

For example, a team from Cyprus, APOEL, reached the quarter finals of the Champions League a decade ago. You might think this was a great underdog story. But the money they got from that run completely destroyed the Cypriot league, because suddenly APOEL’s budget was ten, twenty, or even thirty times greater than that of their nearest competitors.

Not only are the richest clubs in the Champions League much stronger than the poorest clubs, but the poorest clubs are then much richer in turn than their domestic rivals. That skews the domestic competitions, which means that those clubs carry on qualifying for the Champions League and receiving more money. I don’t really know how you put this right without wholesale redistribution, which clearly none of them will ever agree to.

What impact have the Financial Fair Play (FFP) rules devised by UEFA had in terms of leveling the playing field?

In truth, almost nil. They were introduced in 2011, just as Russian oligarchs were beginning to invest in Russian clubs like CSKA Moscow and Anzhi Makhachkala. The story behind Anzhi Makhachkala was bizarre: it seems to have been an idea of the Russian government to go to Makhachkala in the disputed region of Dagestan and give them a top-level European club to calm the waters. They invested enormous amounts of money, bringing in world-famous players like Roberto Carlos and Samuel Eto’o. That wave of investment in Russian domestic football slowed down dramatically after the FFP regulations were brought in.

But in terms of checking what Manchester City or Paris Saint-Germain (PSG) have done, the regulations have had virtually no impact. Every now and then, somebody raises a quibble and there will be an investigation that drags on and on. UEFA doesn’t have the financial clout to legally challenge a state-run club like City or PSG. Those clubs can afford to pay lawyers to drag things out until the statute of limitations has expired.

Manchester City were banned from the Champions League but got off on appeal — not because they hadn’t committed an offense but rather because the offense had been committed too long ago for them to be punished for it. There has been an investigation by the Premier League into payments made by City a decade ago that’s been going on for several years, with no sign of it coming to an end. Even if some punishment is finally imposed, it will be a decade or more after the offense took place, if indeed it was an offense.

In reality, FFP has had almost no impact. We’ve also discovered that state-run clubs have a lot of other state-run entities that can give them lucrative sponsorship deals. It’s almost impossible to say what a fair market price is for those deals.

Would you say the formation of a European Super League is inevitable in the long run, despite the setback to that project in 2021? And if it is, will we even notice the difference by the time that it happens?

I’m loath to say it’s inevitable, but it feels like the direction of travel. I think the Premier League is fine. Even though Manchester City are clearly dominant, having won five of the last six titles, it’s not like Germany, where Bayern Munich have won eleven in a row, or France, where PSG have won nine out of the last eleven, or Italy, where Juventus won nine in a row between 2011 and 2020. In Spain, there’s a very obvious duopoly between Real Madrid and Barcelona — if both of them have terrible seasons, Atlético Madrid can just about pinch the title, but nobody else can.

The leading countries are very worried by that because they realize it’s not a good product if the same team wins all the time. They’ve become trapped in a financial system whereby if a team is successful, it makes more money and can buy the best players. How do you get out of that without breaking the structures completely?

The pandemic has accelerated the process. The Premier League, because it’s wealthier and has bigger TV broadcast deals, was able to ride out the pandemic better than other countries. There’s a lot of economic pressure on the rest of Europe so they look at the Premier League and think “we need a way to combat that.” The Super League seems like an obvious way of doing it.

But how do you actually achieve that goal? PSG were against the Super League, because, I think, their owners were smart enough to recognize that fans don’t like the idea of a closed league. They like the idea that the Champions League is somehow still a meritocracy and that a team can fall or rise. However difficult that may be in practice, it is still at least theoretically possible, which wouldn’t be the case in a closed league. You would have quasi-franchises.

German fan culture would be very much opposed to it. There’s absolutely no reason for the English clubs to get involved and I honestly find it mystifying that so many of them were involved before. It’s significant that many of the clubs that went along with it have American owners who may have seen the possibility of an American-style system — a quasi-franchise system to lock in the revenues. The Premier League has such an advantage at the moment that I’m not really sure why they would give that up.

One key factor is a court case that’s been taken against UEFA by the three clubs that are still invested in the project: Juventus, Barcelona, and Real Madrid. They accuse UEFA of holding a monopoly position. The European courts will decide whether or not UEFA is allowed to hold that position.

If they rule in favor of the clubs, suddenly there will be nothing to stop them from setting up a Super League. Perhaps the leaders of FIFA could stop it, but they might opt instead to sit back and claim a slice of the club revenues they’ve been shut out from, while stabbing their old rivals from UEFA in the back at the same time.

If that was to happen, football might begin to splinter in the same way as golf or boxing. If you ended up with Manchester United belonging to one franchise while Real Madrid belonged to another so they couldn’t play each other, that would be a much less attractive product.

You mentioned earlier the role of Silvio Berlusconi, who famously launched his entire political career on the back of his position as chairman of AC Milan. Today’s generation of club owners don’t seem to be very interested in national political interventions in the way that someone like Berlusconi was. Is that a fair generalization, and if so, why do you think that is?

In Europe, it probably is true. You’ve got the case of Mauricio Macri in Argentina, who was the president of Boca Juniors. In much the same way as Berlusconi, that gained him the popularity and recognition to become president of his country.

But in Europe, the leading clubs are now just too big. An aspiring political candidate couldn’t afford them. In order to buy a club, you have to be either the sovereign wealth fund of a state or else an American hedge fund.

As you’ve alluded to, three major European clubs are now effectively state-run projects of the Gulf monarchies. What does that mean for the game in England, France, and the wider world?

It’s very hard to see it as anything other than terrible, on a number of levels. Take the case of Newcastle, a proud old club that has existed for one hundred twenty–odd years, representing the city and the people of Newcastle. It is now beholden in theory to a Saudi public investment fund, but realistically to the leaders of Saudi Arabia. Who’s to say that, if the oil price falls, they won’t think “we’ll get rid of that, we don’t need it”? And then what are the consequences for Newcastle?

What are their reasons for owning the club? Is it to win matches and titles? Is it to make money, or to promote the image of Saudi Arabia and give it an avenue into the society and business environment of Western Europe? If you believe that football clubs can and should be a representation of their area, that’s a major change.

A lot of Newcastle fans seem quite happy with the deal they’ve done. But you saw with Chelsea what can happen if you get involved in geopolitics. Your owner can suddenly be sanctioned, and then you could realistically be facing bankruptcy. As it is, Chelsea were taken over by Clearlake [Capital] and Todd Boehly, who I don’t think have made a very good job of it so far.

To an extent it’s true with hedge funds as well — ownership has been taken away from the community, and that’s a very dangerous thing. Fifty or sixty years ago, when clubs were owned by a local building magnate or haulier, that person might have had a lot of power, but he was still to some extent beholden to the community from which he came. That dynamic has changed.

The much bigger issue for football generally is that these clubs are not controllable, as I mentioned earlier. If they have the sovereign wealth fund of a state behind them, then how can the [Football Association] or the Premier League or UEFA control them? When it comes to any kind of legal battle, Saudi Arabia can afford the better lawyers and can afford to drag it out. They can win by draining your resources. In that context, the associations and organizations that supposedly provide the governing structure for the game are as good as meaningless.

During the first decade of this century, many English football fans looked to Germany as an alternative model for how football could be run in the modern age that wouldn’t have the same stark inequalities between clubs. Does the hegemony of Bayern Munich over the last decade mean that they had it wrong?

I don’t think they had it wrong, but they possibly hadn’t looked at the bigger picture. I totally get why the German model is attractive. They have the 50+1 rule, which states that the fans must control a minimum 51 percent stake in a club, with a couple of exceptions, such as Bayer Leverkusen, who are owned by the local pharmaceutical firm, and Wolfsburg, who are owned by Volkswagen.

Leipzig are now owned by Red Bull, who have shown that you can drive a truck through the spirit of the 50+1 rule while complying with the letter of it. But I get why that’s attractive — the sense that fans do have control.

German fan culture is also very attractive. When you compare the color and atmosphere of German grounds to the slightly anodyne Premier League crowds these days, you can see why that’s appealing to people. Ticket prices are much lower. There’s a much greater sense of fan engagement on political issues, taking strong stances against homophobia or in support of refugees. All of that is very attractive and I understand why people want to import some of that into the Premier League.

However, it didn’t alter the fact that Bayern were getting richer than everybody else, much quicker than everybody else, and nothing seems to have been able to stop that. That’s partly because Bayern were successful, and partly because Munich is a wealthy city with a lot of sponsors and investors. Bayern have around 70 percent more revenue than Borussia Dortmund, who are the second-richest German club.

Inevitably under those conditions, they win. They possess so much power that they can effectively neuter opponents by buying their best players. Jürgen Klopp’s Dortmund, when they were challenging Bayern, lost Robert Lewandowski, Mario Götze, and Mats Hummels, all to Bayern. It wasn’t just that they sold those players — they sold them to their direct rival.

When you look at German football now, it’s still a great league, but Bayern are so dominant that there’s no sense of a title race. That obviously takes a lot away from the attractiveness of it.

The traditional stereotype presents the US as having a more cutthroat, unregulated version of capitalism than many European states. It’s somewhat ironic in light of that stereotype that top-level American sports appear to be rather more egalitarian than European soccer in various ways, in terms of the draft pick, the distribution of television money, and so on. How did that American sporting model come about, and could it ever be replicated in Europe?

I don’t think it’s quite as straightforward as that. Yes, TV money is much more equitably divided, and you have the draft system, which makes competition much more equal. But that’s actually a very cynical, money-oriented way of doing things, because these are not organic clubs — these are franchises in a cartel. The cartel makes money and in fact it’s almost impossible to lose money, because it keeps everybody going on a level.

There’s no organic sense of a club representing its society, which for me is the great beauty of European football. I’m a Sunderland fan. The football club grew from a teachers’ team in the 1870s. A teacher called James Allen put the team together and it slowly grew into the Sunderland we know today, which has become probably the one thing that Sunderland has left as the heavy industries have fallen away. It’s the one reminder of the city that Sunderland used to be. It’s very difficult to get that with a franchise model.

Could you impose a franchise model on Europe? Let’s say you want thirty-two franchises across Europe — the same number as you have in the National Football League in the US. You wouldn’t put two of those franchises in Manchester and one in Liverpool, or three in London and two in Milan. Yet those rivalries between the Manchester clubs and Liverpool, or between the two Milan clubs, are among the great selling points of European football.

The FIFA president, Gianni Infantino, has the idea for an African Super League. In Africa, you can make the case that football is in desperate need of investment and there is a system of club competition that is less wealthy and less well-established. That’s true to an extent, although the African Cup of Champions has been going since the early 1960s — almost as long as the European Cup.

Infantino’s idea is that you will have a closed league of twenty clubs that share all the investment arising from that between them. But you have an immediate problem: Where do you put those twenty franchises? Do you base them on existing clubs?

How can you choose between Al Ahly and Zamalek in Cairo, or between Raja and Wydad in Casablanca? Those derbies are still one of the big selling points of African football, so losing them would mean losing the one thing that people are still interested in.

The same problem arises in South America. Would you still have River Plate and Boca Juniors, both from Buenos Aires, if you had a league with franchises across the continent? You probably wouldn’t.

That’s an issue for US football. There’s no way for these organic rivalries, which mean so much more than football, to grow up. You can have a rivalry to some extent between New York and Boston (or between New York and New England, in terms of the franchises). But it’s not as visceral and deep-seated as Liverpool vs. Manchester United. That makes it a harder sell to a wider public.