John Fetterman’s Post-Stroke Struggles Are Brave. They’re Also Irrelevant.

John Fetterman’s post-stroke impairment is temporary, it doesn’t affect his cognitive capacity, and plenty of sitting senators have suffered from much worse. So why is his condition getting more attention than his opponent’s sleazy history?

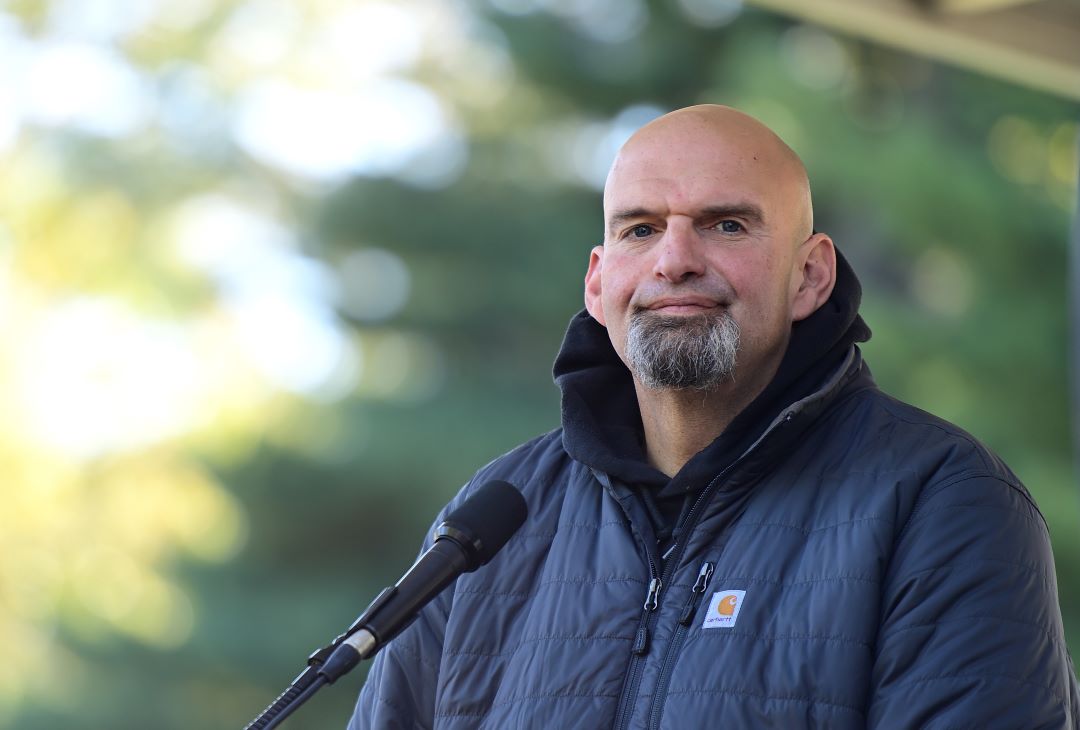

Democratic candidate for US Senate John Fetterman reacts to applause from supporters during a joint rally with Democratic candidate for governor Pennsylvania attorney general Josh Shapiro at Norris Park on October 15, 2022, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. (Mark Makela / Getty Images)

Progressives just can’t seem to catch a break. Pennsylvania lieutenant governor John Fetterman seemed to offer left-leaning Democrats just the kind of candidate who many had argued could win elections in situations where typical Democrats couldn’t: a plainspoken populist who looked and talked like a regular person and who could appeal to both high-education Democratic partisans and the kind of disillusioned Rust Belt voters who went for Donald Trump six years ago.

Then he had a stroke.

A little over a week before the midterms, Fetterman’s near-death experience, which took place five months ago, has perhaps become the issue of his Senate race against Republican and daytime talk show host Dr Oz, which has narrowed recently. If nothing else, it’s certainly become the focus of media coverage of the race, ever since Fetterman sat down for an interview with NBC two weeks ago, giving the country a firsthand look at the extent of the damage the stroke had left on the once front-runner.

According to a medical report recently released by his doctor (who, it has to be said, is also a Fetterman and Democratic Party donor), Fetterman, while physically healthy and getting better, is still suffering from auditory processing disorder, a problem that roughly one-fifth of stroke survivors have to deal with. Those struggling with it have a variety of potential communication issues, including having trouble processing what they hear and finding the right words while speaking, or simply struggling to keep up with conversation. Just like being hard of hearing doesn’t mean someone is mentally disabled, it’s not an intellectual problem, but on the surface, to the unkind and ignorant, that’s exactly what it might look like.

This is what happened with Fetterman’s NBC interview, when the candidate, who had been avoiding public interviews and dragging his feet on debating, emerged in public for what was, for many people, the first time in months. Just as with this week’s debate, Fetterman did the interview while reading live captioning that helped with his post-stroke auditory processing troubles, and his responses were littered with instances of uncomfortably long pauses and garbled words and sentences, with Fetterman often visibly struggling to coherently articulate what he was trying to say.

Right-wing voices like Tucker Carlson who oppose Fetterman have used this to inaccurately charge ― or at least heavily imply ― that this means he’s “mentally defective.” They’ve been inadvertently assisted in this by liberal reporters who, at least on their Twitter feeds if not their columns, reacted to Fetterman’s NBC interview and debate performance with shock and horror at his condition.

Even though his doctor has said that Fetterman “has no work restrictions and can work full duty in public office,” this has all helped create the impression that, if elected, Fetterman would be unable to do the job.

Debate While Disabled

What’s interesting is that despite the media fixation on it, Fetterman’s disability was barely an issue in the debate.

It was, of course, obvious and noticeable throughout, and Fetterman immediately addressed the “elephant in the room,” warning the audience he would miss words or mush them together over the hour. Oz wisely didn’t make it an issue, given the backlash he’d gotten for mocking Fetterman’s stroke earlier in the campaign, and he stuck instead to standard GOP attacks that Fetterman was “radical,” “extreme,” soft on crime, and bad for business.

The disability was unsurprisingly a hindrance for Fetterman. Given fifteen seconds at one point to respond to a litany of charges from Oz, including that he wanted to “legalize all hard drugs” and backed an open border, he struggled to articulate a rebuttal, one of several such instances. But aside from a handful of awkward silences ― as when he was asked if he had any criticisms of Joe Biden ― his performance was notably improved and quicker under these more demanding, high-pressure conditions compared to the NBC interview weeks before, when nearly every question had been met by an uncomfortably long pause.

In fact, Fetterman had some strong moments, landing a decent blow on Oz toward the end over the doctor’s opposition to student debt cancellation by noting he wasn’t as opposed to “free money” when it came in the form of a tax break for one of his ten houses. He even turned the residual effects of the stroke into an early debate highlight, albeit a clearly scripted one not delivered with his prestroke crispness.

“It knocked me down, but I’m going to keep coming back up,” he said about the stroke:

And this campaign is all about, to me, is about fighting for everyone in Pennsylvania that ever got knocked down that needs to get back up and fighting for all forgotten communities all across Pennsylvania that also got knocked down that need to keep, get back up.

Ironically, his worst moments had nothing to do with the stroke. Fetterman had no good answer ― other than repeating “I support fracking” ― for the glaring flip-flop he had made on the issue of fracking in Pennsylvania, undermining the what-you-see-is-what-you-get image that’s key to his appeal. Oz also landed a blow when he said that he, not Fetterman, had been endorsed by the police union in Braddock, where Fetterman had been mayor. Asked what the biggest threat to the United States was, Fetterman answered China, playing into the Republican-driven geopolitical fearmongering that most of the country doesn’t see as much of a priority while missing a chance to talk about corporate domination of US politics or to tie Oz to it.

Oz, meanwhile, appears to have become a more skillful politician, ably dodging questions throughout about how he would have voted on bills that are important to more Democratic-leaning constituencies and spouting stridently moronic nonsense confidently and convincingly. Oz squirmed out of his opposition to raising the minimum wage to $15 by cannily saying he thought the figure was too low but that it would be magically raised by market forces, even as corporations are plowing record profits into stock buybacks.

He slammed the still-dormant Iran deal using the usual right-wing talking points while suggesting the deal involved oil exports. He dodged being pinned down on abortion by taking a state’s rights stance (though he also stepped in it by saying the decision should only involve “women, doctors, local political leaders” — a fringe position if there ever was one).

There are two schools of thought about Fetterman’s debate performance. The Right naturally seized on it to call him unfit to serve or to demand he drop out, while liberals unsympathetic to the GOP deemed it a “disaster,” the assumption being that seeing Fetterman’s disability in action will naturally turn voters off.

Another way to look at it is that voters will understand that Fetterman will eventually get better and that they respect, maybe even find inspiring, his willingness to keep fighting and to debate, despite the risk of embarrassment and mockery and despite the fact that public speaking is still a struggle for him. That’s certainly the opinion of at least some pundits, with the Philadelphia Inquirer’s opinion staff giving Fetterman slightly higher marks than Oz in the debate (which is not saying much, given that score was 4.3/10). The Fetterman campaign says it raised what it called an “unprecedented” $1 million in three hours following the debate, suggesting this may not be entirely wishful thinking.

What Really Matters

Lost in all this are some deeper questions about US governance and political priorities. If Fetterman isn’t actually intellectually impaired ― which he demonstrably isn’t, as both his doctor and reporters confirm ― then does his disability actually matter?

For a candidate, of course it does. Running for office involves making speeches, talking to voters, doing interviews, and debating, and as Fetterman is finding out, when you have an ailment that makes communication difficult, you’re going to have a rough go running an election campaign.

But once you’re in office? The job of an elected official is to sit in Congress, listen to speeches, read and digest briefings, and, ultimately, to put your thumb up or down when you’re asked how you want to vote on a bill. (It also involves a lot of begging for money, though since Fetterman opposes big money in politics, he will hopefully be spared that one). Maybe a hundred or so years ago, someone with Fetterman’s condition wouldn’t have been able to do this job. But in a world where speech can be recorded and recordings can be transcribed quickly and easily with a screen and one can hire people to type out live captions for them ― and, more important, in a modern society where we long ago agreed special accommodations must be made for people coping with disabilities they never asked for ― that’s more dubious.

In fact, it’s more than a little absurd to fixate on Fetterman’s difficulties given that it’s, generously speaking, an open secret that one currently sitting senator is suffering from dementia so severe, she doesn’t recognize her longtime colleagues, and her unelected staff does most of her work for her. There’s barely any media coverage of this even though, unlike Fetterman, Dianne Feinstein has serious cognitive impairment that really does make her unfit to do her job, and none of her colleagues ― even the ones on the other side of the aisle ― are pressuring her to step down.

Fetterman’s case is also hardly unprecedented. Senator Ben Ray Luján (D-NM) suffered a stroke earlier this year, had surgery, and was back in the Senate after a month. Former Republican senator Mark Kirk (R-IL) suffered a worse stroke than Fetterman, and his malady was barely brought up by the press as he served out the rest of his term, ultimately losing reelection. When Senator Tim Johnson (D-SD) came back to the Senate in 2007 after a stroke, he was warmly welcomed back by colleagues from both parties, all of whom insisted that despite his new difficulties with speech, he was still the same person and could do the job.

Meanwhile, taking a backseat during all this is the record and worldview of Fetterman’s opponent. Oz has played footsie with election denial, doesn’t support a higher minimum wage or abortion rights, and backs privatizing Medicare. He’s said that the uninsured “don’t have the right to health,” got wealthy hawking medical quackery to desperate people, and was responsible for breathtaking animal abuse, violating the law by neither drugging nor euthanizing the animals that were harmed in his research. This is just a brief sample of Oz’s record that’s far more relevant to how he would serve as a US senator than whether or not Fetterman can articulate a crisp sound bite.

There’s plenty one can criticize about Fetterman. Besides the fracking flip-flop, he’s been wishy washy on single-payer health care, and he’s taken a craven centrist position on Israel and Palestine. If voters decide, after comparing this to his opponent’s plutocratic policies and history of dishonesty, that they still can’t vote for Fetterman, they have every right to make that decision. But media obsession with a man’s disability shouldn’t decide this election, especially when the press has made it clear they don’t care about cognitive impairment in any other case.