From Post-Politics to Hyper-Politics

If everything is political, then nothing is political.

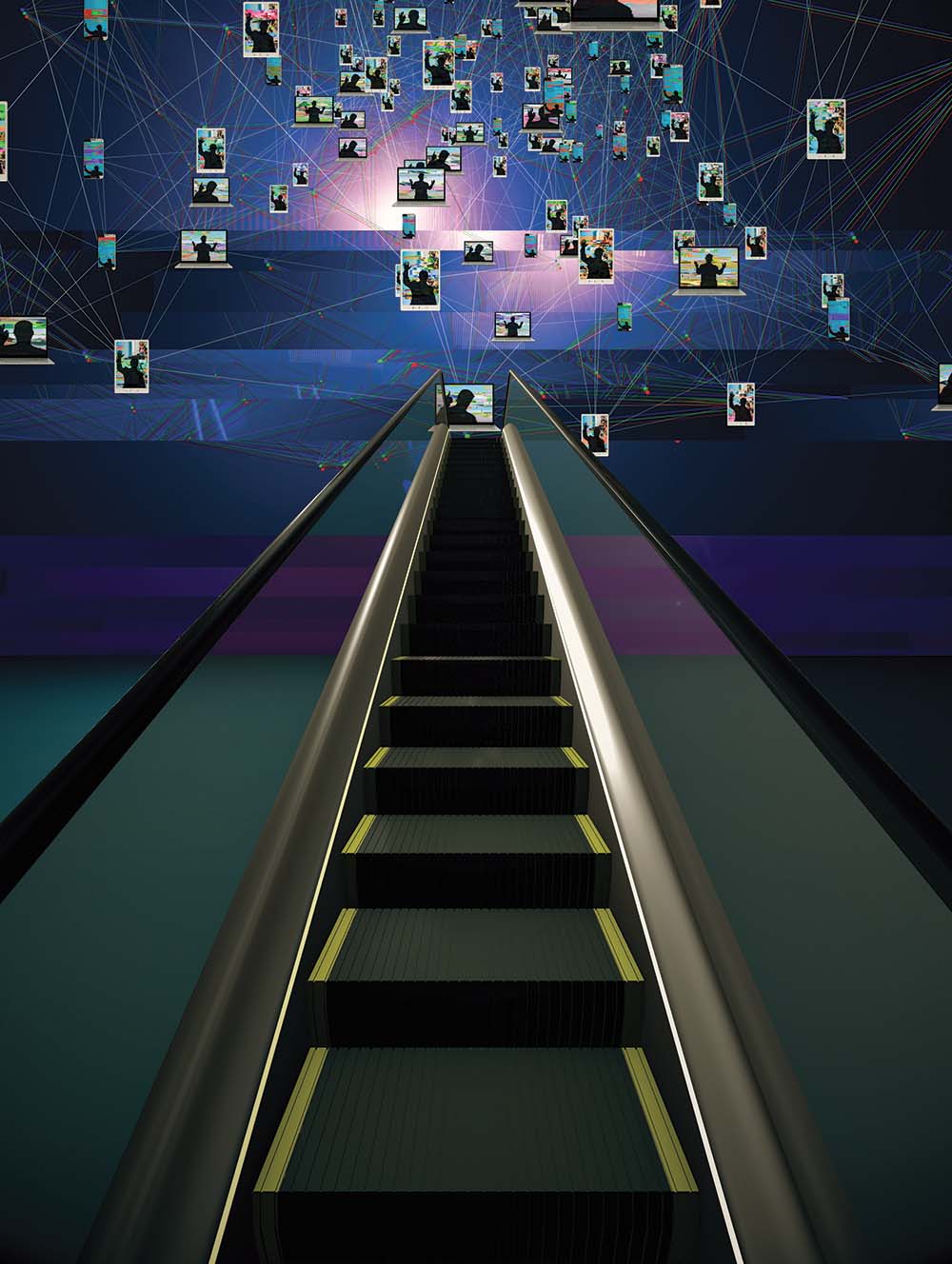

Illustration by Yoshi Sodeoka

Halfway through her autobiography The Years, French novelist Annie Ernaux gives her readers a political panorama of the mid-1990s:

The rumor was going around that politics was dead. The advent of a “new world order” was declared. The end of History was nigh. . . . The word “struggle” was discredited as a throwback to Marxism, become an object of ridicule. As for “defending rights,” the first that came to mind were those of the consumer.

Born to working-class parents in 1940, Ernaux had already grown into one of her country’s most celebrated writers by the end of the 2000s. Published in French in 2008, her “collective autobiography” about postwar French society appeared shortly before Lehman Brothers went bust. An English translation only came about in 2017, already at the close of the “populist” decade.

When it was first published, Ernaux’s work diagnosed a shuttered and claustral world in which people had retreated into privacy, where politics was relegated to the back burner while technocrats were in charge. Tony Blair claimed that opposing globalization was like opposing the changing of the seasons, while the term “Alternativlosigkeit” (alternativelessness) entered the German dictionary.

“We didn’t quite know what was wearing us down the most,” Ernaux recalls of this period, “the media and their opinion polls, who do you trust, their condescending comments, the politicians with their promises to reduce unemployment and plug the hole in the social security budget, or the escalator at the RER station that was always out of order.”

Ten years of populist turmoil later, Ernaux’s testimony appears both familiar and unfamiliar. The rapid individualization and decline of collective institutions she diagnosed has not been halted. Barring a few exceptions, political parties have not regained their members. Associations have not seen attendance rise. Churches have not filled their pews, and unions have not resurrected themselves. Around the world, civil society is still mired in a deep and protracted crisis, with what passes for political action monopolized by flash mobs, NGOs, and philanthropists with weak democratic mandates and nonexistent membership bases. American political sociologist Theda Skocpol rightly speaks of a combination between “heads without bodies” and “bodies without heads.”

On the other hand, the mixture of diffidence and apathy so characteristic of Ernaux’s 1990s hardly applies today. President Joe Biden was elected by a record turnout; the Brexit referendum was the largest democratic vote in Britain’s history. The Black Lives Matter protests were mass events — many of the world’s largest corporations took up the mantle of racial justice, adapting their brands to support the cause. Platforms like TikTok, YouTube, and Twitter are bursting with political content, from vloggers reciting socialist pamphlets to French right-wing influencers raving about refugees. A new form of “politics” is visible on NBA courts and NFL fields, in the most popular Netflix shows, and in the ways people describe themselves on their social media pages.

To many on the Right, society now feels overtaken by a permanent Dreyfus affair — spilling over into family dinners, friends’ drinks, and workplace lunches. To self-conceived centrists, it has created a longing for an era before the new hyper-politics, a nostalgia for post-history in the 1990s and 2000s, when markets and technocrats were exclusively in charge of policy.

That era of “post-politics” has clearly ended. Yet instead of a reemergence of the politics of the twentieth century — complete with a revival of mass parties, unions, and workplace militancy — it is almost as if a step has been skipped.

Those who were politicized by the era surrounding the financial crash will remember when nothing, not even the austerity policies imposed in its wake, could be described as political. Today, everything is political, and fervently so. And yet, despite these wild passions overtaking and remaking some of the West’s most powerful institutions — particularly in the United States — very few people are involved in the kind of organized conflict of interests that we might once have described as politics in its classical, twentieth-century sense, and anti-political sentiment has not declined. The resulting hybrid proves both inspiring and exasperating, but it has not produced the renaissance of class politics that the populist left originally wanted to kick-start.

The Populist Era

To understand the shift from post-politics to hyper-politics, it is worth recalling the shape of the interregnum we’re leaving.

In the years after 2008, the political ice age that had followed the collapse of the Berlin Wall began, steadily, to thaw. Across the West — from Occupy Wall Street in the United States to 15-M in Spain and the anti-austerity fervor in Britain — movements began to emerge that once again raised the specter of competing interests. They did not take place within the formal realms of politics, however, and their “neither right nor left” rhetoric was sometimes described as anti-political. Yet they nonetheless marked an end to an era of consensus.

Across this populist explosion, organizational alternatives to the old mass party model proliferated. Movements, NGOs, corporations, and polling companies with names like Extinction Rebellion and the Brexit Party today offer more flexible models than the working-class parties of yore, which are now perceived as too sluggish for politicians and citizens alike. The people who would have once been party members can now opt out of enlisting in long-term, involuntary associations, while politicians are supposedly met with less resistance at their party congresses.

Strange new forms have since taken the mass party’s place. So-called digital parties — from La France Insoumise and Podemos on the Left to Emmanuel Macron’s La République en Marche! in the center and Italy’s Five Star Movement amorphously on the Right — promised less bureaucracy, greater participation, and new forms of horizontal politics. In reality, they mostly delivered concentrated power for the personalities around which the projects had been built. French far-right candidate Éric Zemmour goes on millennial talk shows while Dutch politicians hold Twitch streaming sessions. As vehicles, parties are slowly dying out or being replaced by cadre organizations. The rest of the party is then retrained as tribunes.

In Britain, the Brexit Party was at least more honest. It established itself as a corporation ahead of the 2018 election and continued as a serious force only if the party proved beneficial to Nigel Farage’s career. All these organizations could claim their roots in the repoliticization of layers of society, but none brought their supporters into what could be described as classical political engagement.

Electoral opportunism is certainly part of the driving force behind this new movementism. For most European parties, the recent conversion to the movement model takes place against the backdrop of a double shift — a long-term decline in the number of party members and a continuous shrinkage in their electorate. Belgium offers a poignant example of this trend. The Flemish Christian Democrats still had an impressive 130,000 members in 1990; they now count a meager 43,000. In the same period, the Belgian Socialists plummeted from 90,000 to 10,000 members. The German Social Democratic Party went from a million members in 1986 to just over 400,000 in 2019, while the membership of the Netherlands’ Labour Party fell from over 100,000 in 1986 to 41,000 in 2021.

Almost everywhere, a similar story is playing out: the former mass party lives on as a supplier of policy (what political scientists call democracy’s “output factor”), but internally, it is eaten up by PR specialists and functionaries. Ernaux’s memoir recounts how the very headquarters of the Socialist Party, which she voted for in 1981, were put up for sale in 2017, after the Socialists were left stranded in fifth place in the country’s presidential elections.

Britain was, to some extent, an exception to this rule. Under Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership, the membership of the Labour Party grew exponentially, from just over 150,000 under previous leader Ed Miliband to close to 600,000 at its height. And these were members, not merely supporters, with a series of constitutional and voting rights — even those who were not regularly involved could show up to constituency meetings occasionally and have meaningful input on questions like who the party’s public representatives should be.

It is clear that this process of repoliticization leaves policy sediments, and even British Conservatives have now been coaxed into using developmental rhetoric, with Boris Johnson explicitly calling for a return to “one-nation conservatism,” the Tory tradition of free-market skepticism. COVID-19 has also dynamited parts of this neoliberal consensus. Governments across the Western world are approaching World War II levels of deficit spending, while the fiscal dam has been broken from Singapore to Budapest.

Apart from China, however, the state has taken on a curiously double role in this process. Welfarism in the twentieth century constituted an experimental program in a mixed economy alongside national development. Spurred on by a fractious but organized coalition between labor and small business, states invested in long-term public services, the electrification of rural areas, and the building of dams, roads, bridges, and other infrastructure. In its most ambitious moments, public money was spent to build public goods with little private sector involvement.

This type of remaking of the economy for the public good has been, so far, completely absent from COVID crisis fighting. Instead, policymakers have opted to replace the invisible hand of the market with the invisible hand of the state — a referee who will occasionally assist the players but rarely, if ever, partake in the game itself. In the meantime, the types of popular mobilization that originally spurred the creation of these welfare states has been inconstant or stymied by reigning party cadres. Unsurprisingly, the Starmerite counterrevolution within the UK Labour Party has focused on targeting members and their powers: if the party is to be made into another vehicle for professional politics, members must be disempowered, incentivized to leave, or outright expelled. With more than 150,000 having already departed, that process is well underway.

The lessons for left populists are bitter enough. While most of the left breakthroughs of recent years (from Syriza to Podemos and La France Insoumise) have sought to express themselves in the form of new organizations, Corbynism was probably the last effort to revive the stodgy working-class parties of the past.

The Flemish Socialist leader, Conner Rousseau, recently celebrated the party’s new climate by welcoming a fresh “start-up atmosphere” within it, showing off his follower count on Instagram. Indeed, parties now regularly put out calls for “social media managers” and spread their messages through influencers — Macron recently hosted two YouTube vloggers in his presidential palace. In the final analysis, these new digital parties and the movements that spawned them were less negations of the postindustrial economy than expressions of it — highly informal and impermanent, without long contracts, arranged around fleeting start-ups and ventures. Unsurprisingly, the low exit costs of these projects are eminently compatible with the mobile lifestyles of networked middle classes.

Citizens who roam from temporary employment to temporary employment find it harder to build lasting relationships in their workplaces. Instead, a smaller circle of family, friends, and online connections now offer a more reliable social environment. Two poles promote either the most concrete or the most abstract types of solidarity — families as private insurance funds, and the internet as an entirely voluntary social arena.

This voluntarism finds clear resonances in the persistent mood of protest so endemic to contemporary politics. On the surface, there would seem to be little that unites the Black Lives Matter protests with QAnon or the January 6 riots in Washington, DC. Certainly, in moral terms, they are worlds apart — one protesting police brutality and racism, the other obsessed with fictitious electoral fraud and conspiracy theory. Organizationally, however, the two movements are similar: they do not have membership lists; they have difficulty imposing discipline on their followers; and they do not formalize themselves into organizations. As roving swarms, they present two options for heroic vigilantism to adherents: either the antifa-aligned guerrillas of the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone, or an Agent Jack Ryan unraveling a Washington conspiracy.

Political theorist Paolo Gerbaudo has described the new protest movements with reference to Deleuze and Guattari’s “bodies without organs” — clenched and muscular, but without a real internal metabolism, subject to constant constipation and impotence. That such a fluid form of authoritarianism, calling on presidents to cancel elections and sidestep parliaments, chimes harmoniously with today’s stagnant service economies is also hardly surprising. An age of changing employment contracts and growing self-employment does not stimulate long and lasting bonds within organizations — about 4 percent of Americans have left the workforce to tend their cryptocurrency revenue in recent years. In the mass party’s place came a curious combination of the horizontal and the hierarchical, with leaders who manage a loose group of loyalists without ever subscribing to a clear party line or discipline.

Works such as German-language author Elias Canetti’s Crowds and Power, originally conceived in interwar Vienna, already recognized this type of leaderism. Canetti’s classic text was composed as a reaction to the great worker uprisings of the 1930s. The interwar workers’ movement provoked an aggressive right-wing counterreaction in the form of fascism, and the period ultimately came down to two organized mass movements — fascists and communists — facing off against each other.

Rather than a mobile “mass,” today’s QAnon troops and anti-lockdown protests look more like swarms: a group responding to short and powerful stimuli, driven by charismatic influencers and digital demagogues — the power to irritate, maybe a few stings here and there, but little more. Anyone can join a Facebook group with QAnon sympathies; as with all online media, the price of membership is very low, the costs of exit even lower.

Leaders can, of course, try to choreograph these swarms — with tweets, television appearances, or supposed Russian bots. But that choreography does not yet summon durable organization. This is a decisive but also unstable shift from mass-based party democracy. Whereas postwar parties had a tight team of midfielders and defenders, the new populist parties are mainly built around their star players. As Gerbaudo again emphasizes, today’s hyperleaders are born media animals.

It is not clear how this populism will be channeled into our new era of public-private protectionism. The more the business of “government” gets left to the central banks, and the more economic policy relies on simple cash transfers, the less socialists have to offer as a philosophical countervision (“Vote with your dollars or euros” seems to be the mantra of the future). If central banks can maintain certain consumption levels through cash transfers, the enormous gaps in inequality, the cannibalization of public services, and the decay of our social infrastructure can continue. Instead of reinvigorating the postwar welfare state, the COVID-19 pandemic could have opened the gateway to a “disinhibited public-private project,” as Adam Tooze recently put it. The vaccine race was itself a monument to this enterprise: the state channels the cash while companies plan and produce. This might indeed be neoliberalism’s end — but whatever comes next might prove more confusing.

Yet the real lesson that has been learned from the “post-political” era is that a modicum of deliberation over collective ends cannot be kept out of the public sphere forever. Without the reemergence of mass organization, this can only occur at a discursive level, arbitrated by media: every major event is scrutinized for its ideological character, producing controversies that play out among increasingly clearly delineated camps on social media platforms and are then rebounded through each side’s preferred media outlets. Through this process, much is politicized, but little is achieved. We can understand this period as a transition from post-politics to hyper-politics, or the reentry of politics into society. Yet our new hyper-politics is also distinct in its specific focus on interpersonal mores, its incessant moralism, and its incapacity to think through collective dimensions of struggle.

A large part of online sociability thus presents us with what Mark Fisher termed “Stalinism without utopia”: an ascetic ethic with highly judgmental norms for interpersonal engagement, rigid enforcement of mores, and libertine abstentionism — now mediated through new digital platforms — but without the utopian calculus that justified the cruelty of the commissar and the party official.

In this sense, “hyper-politics” is what happens when post-politics ends — something like furiously stepping on the gas with an empty tank. Questions of what people own and control are increasingly supplanted by questions of who or what people are, replacing clashes of classes with the collaging of identities and morals.

None of this falsifies the indisputable fact that “post-politics” is ending — “the rumor . . . that politics was dead,” as Ernaux noted in 2008, has died out. A new mode of hyper-politics now seems to offer a feeble alternative to the politics we were familiar with in the twentieth century. Ernaux acknowledges as much — at the end of her book, she calls on readers to “save something from the time where we will never be again,” keeping alive the memory of a world that cannot be recovered, but that is neither entirely lost.