New York State Is Lagging Far Behind on Its Climate Commitments

New York has a long history of setting climate goals to great fanfare — and then missing them. A new climate law makes more promises, but will Governor Andrew Cuomo deliver?

Al Gore (L) shakes New York governor Andrew Cuomo's hand after the governor signed the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (CLCPA). (Luke Franke / Audubon)

Governor Cuomo touts himself as a leader on climate. Like just about any elected Democrat, he says all the right stuff: climate change is an existential crisis, a national emergency, indeed a global emergency. To not address it would be gross negligence.

And to his credit, under pressure from activists, Cuomo has banned fracking, denied major pipeline proposals, and signed the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (CLCPA).

The CLCPA requires New York to slash pollution by 40 percent by 2030 and over 85 percent by 2050, compared to 1990 baselines. It’s a big deal; no other state has set economy-wide pollution reduction targets into law.

“Cries for a new green movement are hollow political rhetoric,” Cuomo declared upon signing the legislation last year, “if not combined with specific aggressive goals and a realistic plan for how to achieve them.”

He’s right: commitments are one thing, follow-through is another.

Any realistic path to the CLCPA’s targets would include huge new solar and wind projects, expansion of mass transit, replacing gas-powered cars and trucks with electric vehicles, and upgrading millions of buildings to high energy efficiency.

All this takes money — but almost no new state funds have yet been allocated.

It would also take a rapid, sustained, and comprehensive regulatory effort. Yet state climate policy and regulation have often been incoherent. For example, the Cuomo administration has granted permits allowing big new fracked gas power plants to be built, while wind and solar projects failed to get state construction permits.

New York has a long history of setting climate goals to great fanfare — and then missing them. Under Andrew Cuomo, the state is on track to miss these latest commitments, too.

“No One Thinks We’ll Make It”

New York is not a leader on climate for a very basic reason: in thirty years, the state’s emissions have hardly budged.

In 1990, New York State belched 236 million metric tons (MMT) of CO2 equivalent into the atmosphere. In 2016, the last time the state comprehensively measured its pollution, its inventory showed 206 MMT of pollution — just a 13 percent drop in annual emissions.

These are conservative estimates that very likely overstate the drop in pollution, since they don’t properly account for increased pollution from more reliance on fracked gas.

The CLCPA promises to break out of that thirty-year holding pattern — and maximize results for historically disadvantaged communities. But it doesn’t offer a blueprint for how we’ll get there.

Rather than laying out enforceable benchmarks and specifics, the act charges a newly appointed Climate Action Council with creating a plan by 2022, which the state’s Department of Environmental Conservation would then turn into specific rules and regulations by 2024. Cuomo’s in control: the large majority of the council’s members are his appointees.

But even getting the Climate Action Council to meet has been like pulling teeth.

Advocates began pressing for council appointments even before Cuomo signed the law in July of 2019. It took until February of 2020 for Cuomo to fill the seats and until March for the council to meet for the first time.

Then, after COVID-19 hit, advocates had to go public with complaints to get a second, virtual meeting scheduled, which didn’t take place until June. Working groups mandated by the law weren’t appointed until late summer.

“We’re good in New York at writing press releases, but we’re a little less perfected at the art of implementation,” said council appointee Gavin Donohue to E&E News. He’s an industry lobbyist, but he’s right about that.

Even if the council hits its deadlines with a coherent plan, the plan it produces won’t carry itself out for free. A study by a University of Massachusetts Amherst team led by economist Robert Pollin estimated the state would need about $5 billion in public spending per year to meet the act’s commitments.

But apart from hiring some new staff members to administer the law, no new state funds have been allocated. Now, with the COVID-19 crisis crushing the state’s budget and making significant funding even less likely, advocates are sounding the alarm that the state is once again falling behind.

But the CLCPA is a law — can’t it be enforced? Isn’t the point of a law that it must be followed?

In fact, the state routinely breaks its own laws, which are often unenforceable in the courts. So it is with the CLCPA: it does not include any legal mechanism for enforcement, such as a “private right of action.” In theory, someone could plausibly sue the state if it misses its objectives — in 2030. By then, of course, it’d be irrelevant.

In public, the state’s experts and administrators project optimism about the CLCPA. They say they recognize a big challenge. Regulators are ready, one senior administrator said in a recent meeting, “to roll up our sleeves and get to work.”

In private, however, experts confess they are skeptical that New York will achieve the CLCPA metrics. “No one thinks we’ll make it,” a well-connected consultant who works with state agencies told me.

A Long History of Broken Climate Promises

History doesn’t provide much reassurance either that the state will meet its climate commitments. New York has a long record of missed objectives, leaving a trail of broken promises made by governors who are long gone when the targets they set come due.

- In 2004, Republican Governor George Pataki set a renewable energy standard for New York’s grid: 25 percent by 2013. It didn’t happen.

- Governor David Paterson upped Pataki’s goal to 30 percent renewable by 2016. When 2016 rolled around, New York hadn’t even hit Pataki’s more modest 2013 goal.

- In 2009, Paterson created a Climate Action Council, issuing an executive order to cut climate pollution by over 80 percent by 2050. This Climate Action Council vanished down the memory hole.

- In 2016, after missing the previous goals, Cuomo upped the ante to a minimum 50 percent renewable electricity by 2030. Then he upped that to 70 percent by 2030.

- Cuomo ordered a study for planning the state’s transition to 100 percent renewable energy in 2017. The study was never released.

- Cuomo called for a multistate program to tackle pollution, then didn’t follow through, and then again called for an interstate approach, which also hasn’t materialized.

- He has set other big goals for after his term ends, such as 850,000 electric cars on the road in 2025. Currently, there are about 45,000.

- The CLCPA’s key requirements are pegged to 2030, with no interim benchmarks for immediate targets in the governor’s current term. By then, Cuomo will have long been out of office.

And if the state stays on its current course, we can say with near-certainty that it will once again fail to meet its commitments.

What Would It Take?

To understand what it would take to actually achieve the CLCPA’s reductions, consider the state’s greatest sources of emissions.

Cars and trucks are New York state’s top source of pollution. As of last year, a mere 46,000 out of about ten million vehicles are electric — less than one percent. More and more high-polluting SUVs are on the road.

Absent a state and federal rescue, the state’s mass transit systems, already underfunded before the pandemic, may soon be forced to cut subway, rail, and bus service almost in half. If people flee mass transit for cars, pollution will rise, not fall.

Energy use in New York State’s several million buildings, from skyscrapers to suburban homes, is the second-largest source of emissions. Almost all buildings are energy-inefficient beasts that run on oil or fracked gas-fueled boilers.

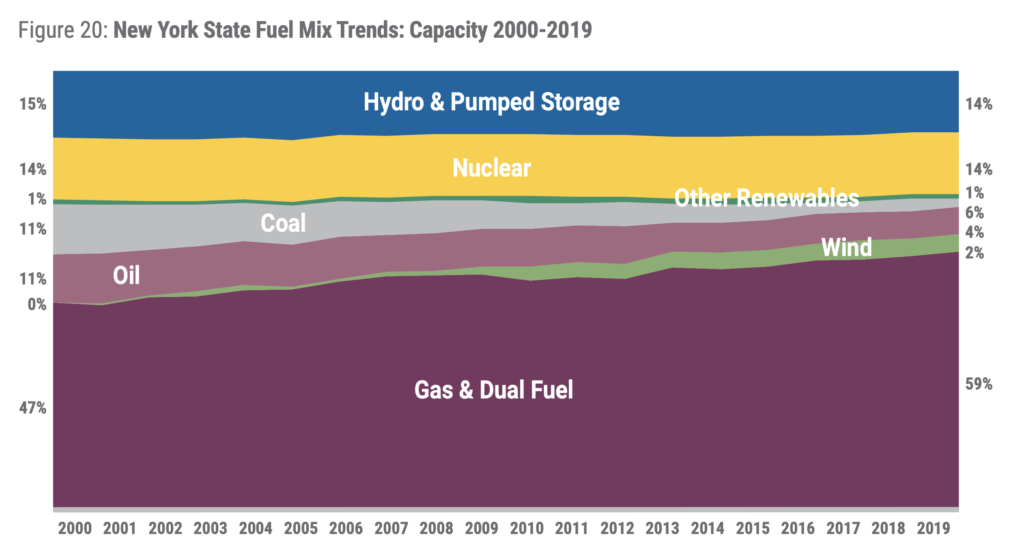

Only 5 percent of the grid’s generating capacity comes from wind or solar, even though the cost of building wind and solar is competitive. Cuomo, famous for flexing his political muscle, hasn’t been using it to close deals on utility-scale solar and wind projects since he took office in 2011 — even as he has approved big new fracked gas power plants.

In each of these areas and others, meeting the CLCPA targets will require a muscular approach, with ample funding and specific requirements backed up by enforcement and penalties.

To slash pollution from cars and trucks, mass transit must be properly funded and expanded as gas-powered cars and trucks are rapidly taken off the road and replaced with electric vehicles.

For buildings, high energy efficiency must be required, with fossil fuel boilers replaced by heat pumps and solar power. New energy-efficient social and supportive housing must be built. Housing infrastructure that’s been neglected, such as the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA), must be renewed and upgraded. Landlords must upgrade rent-regulated buildings to high energy efficiency — without making tenants pay higher costs.

And the state cannot allow any new fossil fuel infrastructure to be built. When you’re in a car headed off a cliff, it’s time to hit the brakes. No more new pipelines and fracked gas power plants. Cuomo must reject each of the polluting power plants projects currently seeking permits, and build new renewables, energy storage, and a modern grid in their place.

Ensuring Equity

All of this must be done with a mind to economic and racial equity.

Fairly distributing benefits and burdens is a matter not only of justice, but also of political necessity. Trying to force down climate emissions on the backs of working people won’t work, as the gasoline tax that helped spark France’s yellow vest movement shows.

Today, electric cars are still more expensive than gas-powered cars, and heat pumps are generally more expensive than a gas boiler. Coupled with requirements to switch to zero-emissions solutions, the state should spend the billions of dollars needed yearly to pay for these types of upgrades for low- and lower-middle-income New Yorkers.

Labor standards guaranteeing good pay and benefits, hiring from low-income and communities of color, and maximizing union jobs should be tied to all state funds and utility-rate–based programs. The new renewable economy shouldn’t replicate the low-wage, low-benefit, low-unionized, discriminatory current economy.

The CLCPA has provisions designed to protect environmental justice, though Cuomo weakened them in the final negotiations with the legislature over the bill. Forty percent of the benefits of clean energy programs are meant to flow to disadvantaged communities. That would be a major accomplishment, if defined correctly, consistently applied and funded.

But early signs are mixed. For example, the governor recently trumpeted a new, up to $700 million program to build electric vehicle charging stations. But because it is funded regressively, through utility bill hikes, and electric vehicles are not affordable to someone with a lower-income, the program runs contrary to the CLCPA’s goals to maximize environmentally just results: it uses poor people’s utility payments to help affluent e-vehicle owners.

A Green New Deal for New York

Enacting the program above to meet the CLCPA’s commitments seems ambitious. But, in fact, the CLCPA doesn’t go far enough.

The UN’s scientists tell us 8 percent cuts are needed worldwide per year through 2030, starting now, to avoid a 1.5 degree future of heating. The CLCPA’s cuts don’t come near that.

Instead, we need the Green New Deal for New York, which would move faster and far more aggressively, for example by taking over the utilities. After all, physics doesn’t care about politics. There’s no negotiating with the atmosphere. New York must cut emissions rapidly or it’ll be complicit in an escalating global catastrophe.

The stakes could not be higher. Absent radical change, swaths of New York will bake in relentless heat waves, large parts of our coasts will drown under rising seas, and extreme weather events that make Sandy feel like a morning dew will pound the coastline.

A New York Green New Deal would need more state money. New York’s rich people, a virtually all-white elite, make so much money that just a 5 percent marginal income tax increase on the top 1 percent would raise about $10 billion a year. That’s in the ballpark of the sum that would be needed.

Right now, a Green New Deal is political fantasy talk. New York is struggling just to get the state to implement the laws and regulations it has already passed.

But there are signs of progress. Progressive challengers running hard on a Green New Deal are unseating incumbents devoted to the status quo. More and more elected officials are embracing a Green New Deal, which is popular with a national electorate and even more popular in deep-blue New York.

Can we mobilize a large enough movement to force our leaders to act? Movements are springing up left and right, from the young people at Sunrise, divestment activists, and youth climate strikers to environmental justice groups mobilizing a real base of community support and Extinction Rebellion direct action hard-liners. These people can make systems move, and anyone who can should join them.

We can’t know if it’ll be enough, in the scant time remaining. What we can say with great certainty is that there’s no option but to try.

Assuming he doesn’t leave New York for some prominent position in a Biden administration, Governor Cuomo will be up for election in 2022. Hopefully, he will soon match his fine words on climate with commensurate action — starting with taking the commitments he signed into law seriously.

If not, someone should run for governor who would.