Eric Hobsbawm’s Marxism Was Central to His Work as a Historian

Some of Eric Hobsbawm’s academic admirers would rather forget about his socialist political commitments. But those commitments formed an essential part of the great historian’s life and work.

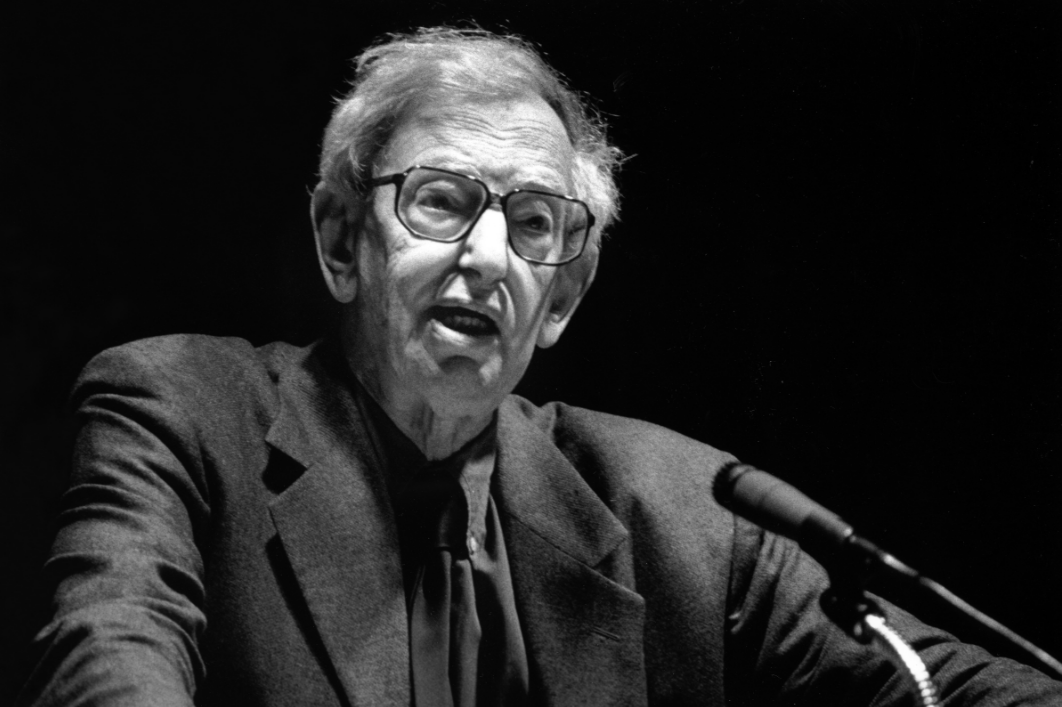

Eric Hobsbawm gives a lecture shortly before his death in 2012.

There have been several studies of the work of the British Marxist historians, but the epic biography of Eric Hobsbawm by Richard Evans is the first to explore the life of one of these figures in any detail.

It is in that respect closer to Jonathan Haslam’s book on E. H. Carr, The Vices of Integrity, than to Bryan Palmer’s study E. P. Thompson: Objections and Oppositions. Evans does of course discuss Hobsbawm’s writings, but his focus here is more on how they came to be written and published, rather than an assessment of their content.

It might be asked whether we require a biography at all. Hobsbawm’s last publication of all-new material was, after all, his 2002 autobiography, Interesting Times. Yet, as Evans points out, one of the peculiarities of that book is precisely how little the reader learns about the author’s inner life.

He quotes one of Hobsbawm’s editors, Stuart Proffit, to the effect that the first draft had been “a rewriting of Age of Extremes from the personal perspective”; but this was still true of the version which appeared in print. In a sense then, the books have to be read together to get a rounded picture of their subject: Hobsbawm’s for his Times, and Evans’s for his Life.

Hidden Treasures

Although the recreation of that life by Evans is not an “authorized” biography, he was given access to Hobsbawm’s personal papers (now at the University of Warwick), and draws on an extraordinary range of unpublished material, including his diaries. These are especially important in revealing hitherto unsuspected aspects of Hobsbawm’s personality and the range of his interests.

His use of metaphors drawn from the natural world, which suffuse his four-volume history of capitalism, becomes less surprising as a literary device when we read passages such as one written in his late teens during a tour of the West Country, which Evans describes as conveying “an almost ecstatic feeling of communing with nature.”

In political terms, however, perhaps the most important new source which Evans deploys are the MI5 reports on Hobsbawm’s activities, which begin in 1942 during his wartime service in the British Army and end with his visit to Cuba in 1962.

Figures subject to the attention of the security services for political reasons do not often become what the final chapter of Evans’s book calls a “National Treasure,” unless it is preceded by extensive recantation. It may be worth reflecting on just how extraordinary it was for Hobsbawm, a self-proclaimed Marxist, to have attained this status, one consummated by his receipt of the Companion of Honour in 1998.

Furthermore, unlike the majority of his contemporaries in the Communist Party Historians’ Group, Hobsbawm retained his membership of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) throughout his adult life, until the organization finally collapsed in 1991 after the fall of the Stalinist regimes in Eastern Europe and Russia.

These may well be credentials which help to gain popularity in areas of the Global South such as Brazil, where he achieved his greatest book sales, or which are compatible with receiving prizes and honorary degrees across Europe. They are not usually to be found in members of a group that includes David Attenborough and Olivia Coleman.

Uneasy Acceptance

One explanation might be that Hobsbawm was subject to a classic British Establishment strategy of neutralization by incorporation. If this is so, then it is one which was adopted only after he entered his eighth decade.

As Evans details, Hobsbawm had one major book (The Rise of the Wage-Worker) turned down for publication in the mid-1950s, and was routinely rejected or “overlooked” for a professorial post until 1970, eight years after the appearance of The Age of Revolution, a book which had very quickly achieved classic status. Neither his opinions nor his willingness to publicly express them underwent any particular change, even as his fame and popularity in his adopted country grew.

The publication of Age of Extremes in 1994 saw him receive perhaps the ultimate sign of acceptance: an appearance on the BBC’s Desert Island Discs. But as Evans recounts, even on that occasion, the presenter Sue Lawley made no reference to his work, and spent virtually the entire program questioning Hobsbawm on his politics and particularly his support for the Soviet Union — a type of interrogation to which no other interviewee had been subjected in the program’s (at that point) 53-year-old history.

This relatively trivial but revealing episode indicates that Hobsbawm’s position in the Firmament of National Treasures remained provisional, at least in some eyes. Indeed, his refusal to play the role of ex-Communist penitent seeking to atone for the sins of his youth continued to enrage right-wing critics even after his death. I will return to the subject below; but for now, how has Evans approached his task?

Creative Tension

There has been a fad in recent years for biographers to affect an unwarranted intimacy with their subjects: Gareth Stedman Jones’s references to “Karl” throughout his book on Marx, Greatness and Illusion, offer perhaps the most egregious example. Where author and subject did know each other, as is the case here, the former may legitimately refer to the latter on first-name terms, but his degree of personal familiarity with “Eric” does not prevent Evans from achieving the degree of detachment necessary to provide a balanced account.

According to his own testimony, although he knew Hobsbawm for a number of years, they were not particularly close: Evans confesses to being too much “in awe” of him for a deeper friendship to develop. In any case, their acquaintance does not appear to have influenced Evans’s judgements.

More important than these personal contacts, perhaps, is the existence of a degree of creative tension between the biographer and his subject, particularly when both share the same social role — in this case, that of historians with well-defined political positions. Where methodologies are similar and beliefs shared, the absence of such a tension can point toward hagiography; where methodologies are mutually incomprehensible and beliefs antipodal, the excess of tension tends toward the hatchet-job. Neither of these extremes is present here.

The main area where the work of the two men has converged is over the subject of history itself, in the case of Evans inspiring three books (In Defence of History, Altered Pasts and Cosmopolitan Islanders), and in Hobsbawm’s a collection of essays (On History). What links them is, among other things, an (in my view) entirely justifiable hostility to postmodernism. In most other respects, the scope of their work as historians could not have been more different.

Hobsbawm was famously polymathic, his areas of interest stretching from micro-studies of highly specialized areas (some of his own invention) like “social banditry” and “primitive rebellion,” through to the global history of capitalism, and the books which constitute the latter — perhaps his greatest achievement — are works of synthesis. Evans’s oeuvre, on the other hand, has been mainly focused on various aspects of the history of modern Germany, and is firmly rooted in his archival research, although more recently he has ventured into Hobsbawm’s territory with The Pursuit of Power: Europe 1815–1914.

Marx and History

However, the most obvious difference between the two men, as historians, is that Hobsbawm was a Marxist and Evans is not. How significant is this? Evans writes:

Throughout his career as an historian, Eric was pulled one way by his Communist and, more broadly, his Marxist commitment, and another by his respect for the facts, the documentary record and the findings and arguments of other historians whose work he acknowledged and respected.

Most of his assertions about Hobsbawm’s approach to history are defensible, but this one is not. I think there are two issues here.

The first is that there is a necessary commonality between Marxist and non-Marxist historians. Both must have the same “respect for the facts” in order to be taken seriously at all, and I know of no occasions where Hobsbawm was “pulled” into misrepresenting or omitting facts in order to defend a thesis.

Interpretations are obviously different: I am also a Marxist, but disagree with Hobsbawm’s claim in his essay “The Forward March of Labour Halted?” that the British working class began numerically to shrink from the 1950s. That “factual” disagreement however rests on a prior theoretical difference about how one defines the working class, and consequently who gets included in the category. And this type of procedure is necessary for all historians, regardless of their doctrinal denomination.

In any case, it is not true that being a Marxist necessarily involves holding to a version of events which is completely at odds with other interpretations. As Evans points out, the chapter order in each of the Age of … volumes is structured by Marx’s base/superstructure metaphor: all four begin with developments in the economy, and end with those in culture and science.

But within that overarching presentational structure, many of Hobsbawm’s judgements would be shared by non-Marxist colleagues. Is, for example, Evans’s discussion of the rise of fascism in Germany in his book The Coming of the Third Reich really incompatible with or in contradiction to Hobsbawm’s inevitably more compressed account in Age of Extremes?

One reason why it is not may be that many aspects of Marxism have long since been absorbed by non-Marxist historians. As Hobsbawm himself wrote in his 1984 essay “Marx and History”:

Marxism has so transformed the mainstream of history that it is today often impossible to tell whether a particular work has been written by a Marxist or a non-Marxist, unless the author advertises his or her ideological position.

Even the more intelligent right-wing intellectuals are aware of this. Hugh Trevor-Roper, with whom Hobsbawm first clashed during the 1950s over the General Crisis of the Seventeenth Century, reviewed On History in terms which were extraordinarily positive about the influence of Marxism, as “a contribution to historical philosophy” which might “continue, revised and modified, to enrich our studies.”

“Not Willing to Submit”

The second issue is the relationship between what Evans calls Hobsbawm’s “Communist and, more broadly, his Marxist commitment.” Rather than being interlocked, as this suggests, I think Trevor-Roper was closer to the truth in thinking that — as Evans puts it — “Eric’s Communism could and should be separated from his Marxism.” Thanks to Evans’s work, we can now see for the first time the extent of Hobsbawm’s alienation from the party to which he nevertheless remained committed for so long.

Much of this new information is available thanks to the MI5 recordings of meetings and phone calls which Evans deploys to particularly good effect. After being a loyal member of the CPGB for 20 years, the events and revelations of 1956 brought him into conflict with its leadership and structures, as much over the question of internal democracy as over the actions of the USSR, to the extent that Party officials wanted him to resign like his fellow historians Edward Thompson and Christopher Hill.

But Hobsbawm seems to have been influenced both by Isaac Deutscher’s advice that he should let the leadership try to expel him rather than leave of his own accord, and by his own unwillingness to join the ranks of “ex-Communists.” Evans sums up Hobsbawm’s dilemma thus:

On the one hand he was wedded at a very deep emotional level to the idea of belonging to the Communist movement, but on the other hand he was absolutely not willing to submit to the discipline the Party demanded. His refusal to toe the line led to considerable frustration in the Party leadership, who knew his value but hated his lack of discipline.

It is not clear to me how someone who rejected the most basic forms of discipline and who actively sought to persuade people not to join the CPGB — as he did with Donald Sassoon in 1971, telling him “you’re going to spend all your time fighting against Stalinists” — can be considered a party member, in anything other than the formal sense of possessing a membership card. In fact, Hobsbawm’s attachment to “Communism” seems to have had two main sources.

The Popular Front

One was his admiration for the role played by the USSR, first in defeating fascism and then in acting as a counterweight to US imperialism. This did not mean that he regarded the USSR as a model for socialism, although perhaps he only felt able to voice the extent of his objections once the regime had collapsed.

Evans refers to an interview with Hobsbawm conducted by Paul Barker for the Independent on Sunday soon after of the fall of the Berlin Wall. Here, he said of the Soviet Union (in a passage not quoted by Evans) that it “obviously wasn’t a workers’ state . . . nobody in the Soviet Union ever believed it was a workers’ state, and the workers knew it wasn’t a workers’ state.” Hobsbawm never explained his position on the nature of the USSR in positive terms, but it is clear that his residual support for it was based on what it did, rather than on what it was.

The other source was Hobsbawm’s enduring belief in the efficacy of the Popular Front as a universally applicable strategy for the left. In a way this is understandable. He had been in Germany until months before the Nazi seizure of power and saw the disastrous consequences of the ultra-left “class against class” policy, in which the German Communists had refused to unite with the supposedly “social fascist” Social Democrats.

Conversely, he had also been in Paris during the celebrations that followed the election of the Popular Front Government in 1936 — one of the few episodes recounted in Interesting Times when Hobsbawm conveys to the reader his own personal sense of excitement and possibility, and one to which Evans rightly devotes considerable space.

At Close Quarters

But the Popular Front strategy — which involved the Communist Parties allying with forces to their right (and where they had the opportunity, violently repressing those to their left) — was in its own way also disastrous, equally unable to resist fascism in France and Spain. It is only by a sleight-of-hand, in which the USSR’s wartime alliance with the USA and the UK is also treated as a species of Popular Front, that it can be said to have “succeeded.”

Yet it remained the centrepiece of Hobsbawm’s political thinking until the end, forming the basis of his arguments for reaching out to the British Labour right and the Liberal Party in the debates which followed the publication of “The Forward March of Labour Halted?” in 1978.

So, when Evans argues that the real difference between him and Hobsbawm lay in their respective political positions, I remain unconvinced. “I have always been a social democrat in my political convictions”, he writes:

I could never accept the fundamental premises of Communism, least of all after seeing at close quarters what they produced in the grim, grey and joyless dictatorship of Communist East Germany when I got to know it during the researches I carried out for my doctorate in the early 1970s.

Leaving aside the question of whether East Germany or any of the other Stalinist regimes could seriously be described as “Communist” — Marx himself observed that we do not judge either individuals or social systems on the basis of their self-evaluations — it is not clear that Hobsbawm’s domestic political perspectives were, in practice, very different from those of Evans.

Indeed, Evans notes this himself in the book’s conclusion:

In terms of practical politics, [Hobsbawm] was always closer to the British Labour Party, even after he transferred his loyalties from the British to the Italian Communist Party. He was never a Stalinist and his belief that the Left needed to acknowledge the crimes and errors of Stalinism was a central feature of his ideological break with the Party in 1956.

A Nineteenth-Century Historian

Is it possible for someone with such moderate left politics to be a Marxist in their historical work? Some of Hobsbawm’s more sectarian critics have doubted it. Evans cites an essay by the Scottish historian James D. Young, who accused Hobsbawm, among other things, of condescension towards the more anarchic popular movements — a stance supposedly indicative of both his authoritarianism and his admiration for the establishments of the UK and USSR alike. Young’s ravings need not detain us, but there is the ghost of a serious point in his claims.

Part of the understanding which Hobsbawm reached with the leadership of the CPGB was that his historical work would not deal with the twentieth century — in other words, with the period from the Russian Revolution onwards. Consequently, as he writes in Interesting Times:

I myself became essentially a nineteenth-century historian . . . given the strong official Party and Soviet views about the twentieth century, one could not write about anything later than 1917 without the likelihood of being denounced as a political heretic.

He maintained this stance until the fall of the Soviet Union and the dissolution of the CPGB released him from any obligation to remain silent.

The consequence was that for most of his life, there was a disconnect between his historical work and his interventions in contemporary politics. The former focused on periods dominated by the various forms of the bourgeois revolution, and during which international working-class revolution only became a realistic possibility towards the very end; the latter attempted to influence the left in a situation where he was sceptical about the future of revolution, at least outside of the Global South.

Although the last collection of Hobsbawm’s essays to be published during his lifetime was called How to Change the World, his work as a Marxist historian was always far more concerned with How the World Changed. And this may explain the extent to which Hobsbawm ended up as a recipient of the Companion of Honour — not because he “sold out,” but because his Marxism was entirely directed towards explaining the past, while his essentially reformist positions about the present were not a threat to the system, particularly once the Cold War had come to an end.

Passing Judgement

I noted at the beginning of this review that, in so far as Evans is concerned with Hobsbawm’s works, it is mainly in relation to their composition, publication and reception, rather than the arguments they contain. He largely refrains from making assessments, apart from occasionally relaying what critics have said and perhaps indicating his agreement or otherwise.

There are points, however, where Evans is unnecessarily critical of his subject. Towards the end of the book, Evans refers to Hobsbawm’s three major “blind spots” concerning Africa, modernism and the history of women. Certainly, the first is mainly absent from his work, and his treatment of the third inadequate, but Hobsbawm’s discussion of Modernism in Age of Extremes and Behind the Times actually displays his strengths as a Marxist historian. He discusses that tradition within the material context of modernity, and traces its failings to an inability to respond adequately to developments in communicative and productive technology.

Nevertheless, Evans’s book is a major contribution to our understanding of one of the great historians of the twentieth century. The occasional contradictions which it contains are perhaps unavoidable when dealing with such a contradictory subject.

At one point, Evans quotes Hobsbawm contemplating the “obsolescence” of his work, while conceding that “only the future can decide.” Indeed: but as long as his books are read, it is probably safe to say that Evans’s monumental history of their author will be read alongside them.