Toronto Is Segregating Dissent

In the wake of protests over West Bank real estate, Toronto has ring-fenced public space around dozens of synagogues. This expansion of “bubble zones” has less to do with real danger than with political lawfare against critics of Israel.

Acknowledging the rise in anti-semitic incidents does not require curtailing lawful protest. Toronto’s “bubble zones” replace targeted law enforcement with restrictions on constitutionally protected expression. (Mert Alper Dervis / Anadolu via Getty Images)

Gidon Katz makes no apologies for marketing West Bank settlements to Diasporic Jews. Katz, an Israeli promoter, has organized real estate shows for more than two decades, including the Israeli Real Estate Event held on synagogue premises in Canada and the United States in March 2024.

While most of the real estate on offer was in Israel, one vendor marketed properties in Efrat, an Israeli settlement in the West Bank established in 1983 on confiscated Palestinian land that continues to expand. Efrat is located just south of Bethlehem, one of 165 noncontiguous enclaves administered solely or jointly by the Palestinian Authority (Sectors A and B). These enclaves are islands in a contiguous “sea” surrounded by Israeli-controlled Sector C, including Efrat and more than 60 percent of the West Bank.

Canada considers Efrat and other Israeli settlements to be in violation of the Fourth Geneva Convention. In 2024, the United States reconfirmed that the settlements are inconsistent with international law. Katz has argued that Efrat should be understood as part of a “settlement bloc,” areas around which Israel has built its separation barrier. Israeli political consensus holds these should be annexed in negotiations with Palestine. The twenty-four-hour checkpoint that leads from Bethlehem to Efrat is closed to Palestinians.

Preventing Protest

The event organized by Mr Katz was held in Thornhill, a suburb of the City of Vaughan, which with Toronto and other municipalities makes up the Greater Toronto Area (GTA). Like many large urban areas, the GTA contains geographic concentrations of ethno-cultural groups, with Jewish Thornhill being a well-known ethnic enclave. Thornhill has the largest concentration of synagogues in the GTA, including the Aish Thornhill Community Shul (Aish Shul) and the Beth Avraham Yoseph of Toronto (BAYT).

A few days before the Katz-organized event, a separate Israel real estate event was held at the Aish Shul. Although the promoter later clarified that no West Bank properties had been marketed there, the event attracted protesters opposing the sale of West Bank land. During this protest, some demonstrators were assaulted by a nail gun–carrying Vaughan resident, Mr Ilan-Reuben Abramov, who was charged with assault, mischief, and other crimes. Police determined that hate was a motivating factor after Mr Abramov was recorded shouting “Every f–king Palestinian will die.” As such, each of these charges — from assault to mischief — is classified as a “police-reported hate crime,” a designation we will return to below.

Tensions were high at the Katz-organized event at BAYT. Held on the synagogue’s second floor, police separated the “Palestine is not for sale” protesters, many of them Jewish, across Clark Street from counterprotesters in front of the synagogue. Unable to maintain complete separation, police made three arrests at the scene for counterprotester attacks against demonstrators: Mr Kevin Haas (possession of a weapon for a dangerous purpose), Mr Meir Gerichter, an IDF veteran (assault by kicking), and Ms Ina Sandler (possessing a weapon dangerous to the public and assault with a weapon). Subsequently, the assaulted demonstrator, Ms Ghadir Mokahal, was charged with mischief under $5,000 for damaging an Israeli flag, apparently carried by Mr Gerichter.

The mainstream media and political response to these incursions into a Jewish neighborhood was swift, framing synagogues as being targeted. This account omitted two critical facts: first, that protests targeted secular commercial real estate events held at dual-purpose spaces rented out by synagogues, not worship services; and second, that no demonstrators were charged with hate or violence-related crimes, whereas three counterprotesters faced assault charges, one of which was designated a hate-related assault.

Encouraged by mainstream Jewish organizations, the City of Vaughan passed a “bubble zone” bylaw in June 2024 prohibiting “nuisance demonstrations” within one hundred meters of “vulnerable” institutions, including places of worship and schools. Critically, the bylaw’s threshold is not actual criminal conduct, but rather the subjective standard that a “reasonable person” hearing certain “views” would feel “concerned” for their safety.

The Canadian Civil Liberties Association (CCLA) challenged the bylaw’s constitutionality, arguing that it is redundant given Canada’s existing laws and that its restrictions on Charter-protected freedom of expression are “breathtaking.” CCLA warned that marches would “be made more difficult, if not impossible,” effectively ring-fencing most of Jewish Thornhill beyond the reach of protest.

In subsequent months, the cities of Brampton and Oakville followed with their own bubble zones. After a public consultation in which most respondents — including labor groups, constitutional lawyers, and Jewish advocacy groups — voiced their opposition, the City of Toronto passed its own bylaw in May 2025. Although somewhat narrower than Vaughan’s, it is likely unconstitutional, as it restricts Charter-protected expression, specifically “objection or disapproval” that does not meet the threshold of hate speech, which Canadian jurisprudence sets at “extreme detestation and vilification.” Unlike Vaughan’s blanket coverage, Toronto’s bylaw requires institutions to opt in. By the end of 2025, forty-six entities had done so, forty-two of which were Jewish institutions, accounting for 91.3 percent of bubble zones, while Jews account for 3.6 percent of Toronto’s population. These forty-two zones account for roughly 210 acres of Toronto’s geography — and counting.

Freedom of Expression and Assembly

Bubble zones raise fundamental questions about when restrictions on constitutionally protected expression and assembly are justified. Is the rising anti-semitism after October 7 such a circumstance? If so, is it reasonable to provide synagogues and other Jewish institutions with exceptional protection from non-hateful expression via bubble zones?

In Canada, freedom of expression and assembly can only be restricted to “such reasonable limits prescribed by law as can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society.” The Supreme Court has established that any such restriction must meet a three-pronged test: rational connection, minimal impairment, and proportionality. This test requires a very high threshold of evidence, which the government must provide if challenged.

While constitutional lawyers and political analysts have commented on bubble zones, to date there has been no empirical analysis of the evidentiary rationale for them. The following addresses that gap by analyzing Toronto police–reported hate crime data from 2018 to 2024. In Canada, there are two types of “hate crimes,” one specific (such as advocating genocide or willfully promoting hatred), and the other general, which can be attached to any other crime motivated by hate. Hate crime is typically a very small portion of all crime; for instance, hate-related assaults accounted for less than 0.5 percent of all assaults in Toronto over the 2018–2024 period.

I focus on violent crimes against persons (assaults) for two reasons. First, the only other bubble zones that have been found constitutional are those around abortion clinics in British Columbia, after the court found sufficient evidentiary basis to justify the “exceptional infringement” of rights, including physical assaults of patients by protesters and the attempted murder of a clinician. Second, the fear of anti-semitic physical violence is both a specific legal concern motivating the Vaughan bylaw and the driving rationale for many Toronto bylaw proponents. Toronto councillor James Pasternak argued that the bylaw was needed because “People are fearful,” while Councillor Diane Saxe argued “My (Jewish) community has never been less safe in Toronto since 1933.”

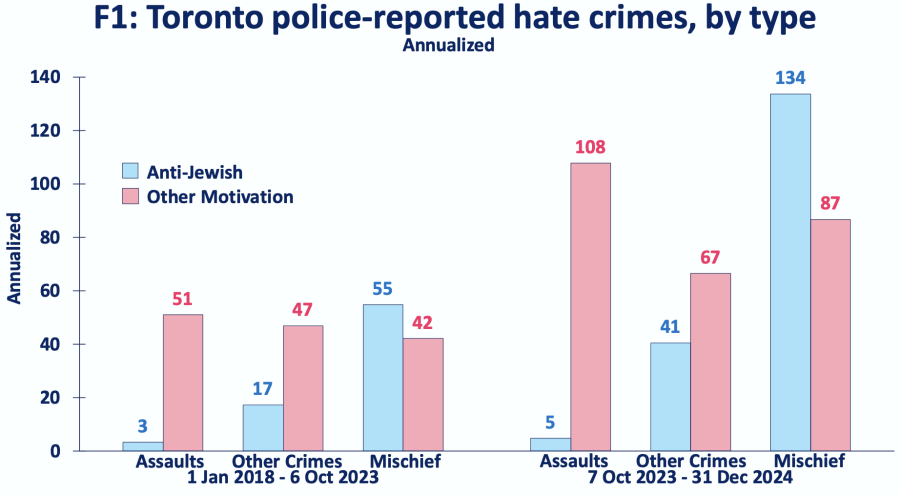

Figure 1 presents annualized hate crime data, separating anti-Jewish from other motivations across three categories: 1) assault, 2) mischief against property under $5,000 (typically graffiti or vandalism), and 3) other residual crimes that do not include violent crimes against persons, such as mischief over $5,000 or harassing communications.

Hate crime increased across the board after October 7. Of particular concern are a doubling of assaults motivated by other forms of hate and a more than doubling of anti-Jewish mischief. These latter data confirm what Jews in Canada and elsewhere have long known: they are disproportionately targeted by this form of symbolic hate. These offenses warrant serious investigation and response, but bubble zones do nothing to address them. Harassment, intimidation, hate speech, obstruction, and other forms of targeted abuse are already criminalized and should be enforced as such; bubble zones instead restrict constitutionally protected expression and assembly, making them both redundant and overbroad.

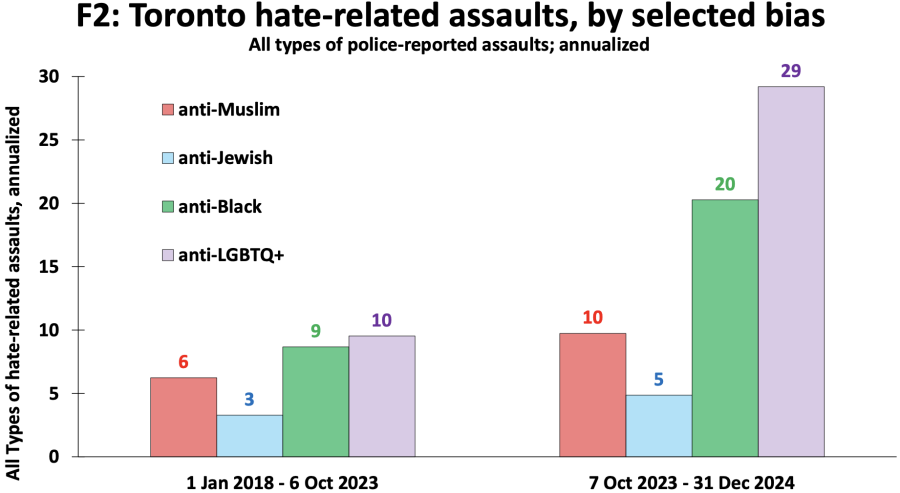

Figure 2 breaks down hate-related assaults, showing that anti-Jewish assaults were fewer than anti-Muslim, anti-black, and anti-LGBT assaults, both before and after October 7. The higher number against Muslims reflects Canada’s recent history: all ten hate-motivated or terrorist-designated religiously motivated homicides in the past decade have targeted Muslims, including the 2017 Quebec City mosque attack that killed six worshippers and the 2021 London, Ontario attack that killed four members of a Muslim family. Hate-motivated attacks targeting Jews have occurred outside Canada, most recently the October 2025 Manchester, UK synagogue attack that killed two.

The Toronto police database also tracks location data and tells a different story: none of the twenty-five anti-Jewish assaults during the 2018–2024 period occurred at a “Religious place of worship/cultural center.” Rather, the most common location, accounting for just under half of assaults, was “Street/Roadways/Highway.”

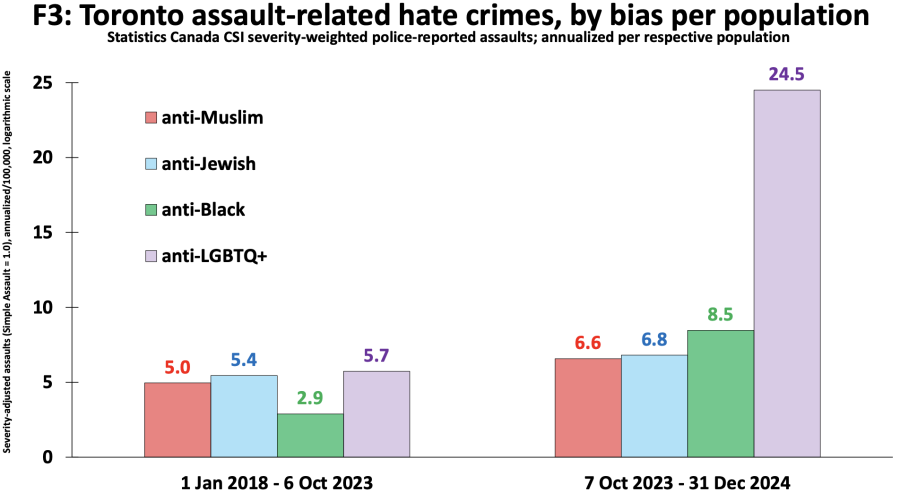

Canada’s Criminal Code grades assaults by severity. Figure 3 applies Statistics Canada’s Crime Severity Index (CSI) to annualized hate-related assaults, adjusted for population. The figure reveals a large increase in anti-LGBT and anti-black assault after October 7. Anti-Jewish and anti-Muslim assaults are comparable to each other and lower than both anti-LGBT and anti-black assaults in the same period.

Fear and the Politics of Safety

Based on this first empirical analysis of violent crimes against persons in the form of assaults, there is no evidence of high or increased violent anti-semitic incidents in Toronto, including at religious places of worship and cultural centers, that would provide the evidentiary rationale for restricting constitutionally protected freedoms of assembly and expression through bubble zones. So if Toronto bubble zones cannot be “rationally connected” to physical violence in Toronto, as constitutionally required, what is their function, and why are they being passed?

One reason is that many Jews in Toronto express concerns about their physical safety and, along with mainstream Jewish organizations and politicians, welcome bubble zones as a response. What explains this gap between objective reality and subjective perception?

Sociology professor Robert Brym, a distinguished and longtime analyst of Jewish life in Canada and elsewhere, offers insight through recent survey-based research. His 2024 study found that Canadian Jews’ hierarchy of discrimination has shifted after October 7: they now rate themselves as the country’s most discriminated-against group. Brym contrasted attitudes toward Jews, which remain largely positive overall, with anti-Jewish incidents. He found that only 9 percent of non-Jewish Canadians hold anti-semitic attitudes, concluding that “contrary to the picture painted by many media outlets, these results do not suggest that a wave of anti-semitism has engulfed the general population.” Brym did find increasing concern about personal safety, which he linked to emotional ties to Israel. Eighty percent of Canadian Jews with strong attachment to Israel reported a diminished sense of personal safety, compared to only 20 percent of those with weak attachment.

Since Israel was physically attacked on October 7, many Canadians have criticized the country’s military response and how its policies contributed to famine in Gaza. Brym concludes that these events explain why Canadian Jews with strong emotional attachment to Israel feel unsafe: “they consider support for Israel a core element of their identity as Jews.”

From this perspective, fear of anti-semitic violence in Toronto appears rooted in perceptions shaped by symbolic hate and political criticism of Israel, rather than grounded in actual local physical violence. Bubble zones are ineffective at addressing either of these.

Political Lawfare Against Israel’s Critics

One strategy for deflecting political criticism of Israel in Canada involves constructing a false “hierarchy of hate” that presents Jews as the “most targeted” group and therefore uniquely in need of protection, including through bubble zones. Such a narrative obscures the fundamental distinction between symbolic hate and actual physical danger. Crucially, it also inverts the actual pattern of violence at the real estate protests: demonstrators faced assault charges from counterprotesters, not the reverse. Yet this fact was largely absent from the political and media framing that justified bubble zones.

The political urge to “do something” has escalated dramatically. What began as a response to protests against the marketing of confiscated West Bank land — territory from which Palestinians are barred — has evolved into bylaws restricting expression across most of Jewish Thornhill and approximately 210 acres of Toronto. The scope continues to expand.

At best, the Toronto bylaw represents unconstitutional overreach with no rational connection to demonstrated risk to physical safety; at worst, it constitutes lawfare against political critics of Israel. Jewish constitutional lawyer Joanna Baron, in her article “Jews Don’t Belong Behind Civic Moats,” identifies the historical stakes. Bubble zones carry serious precedent risks: historically, special protections cordoning off public space for Jews resulted in ghettos. As she warns, “we must resist the impulse to trade liberty for the illusion of security . . . by curbing the very freedoms that have long protected minority communities in liberal democracies.”