Oasis’s Working-Class Image Is Seductive but Empty

English rock group Oasis has always been a populist contradiction, rooted both in working-class culture and the individualism of post-Thatcherite Britain. But while other bands become more political, Oasis’s comeback tour offers only escapist nostalgia.

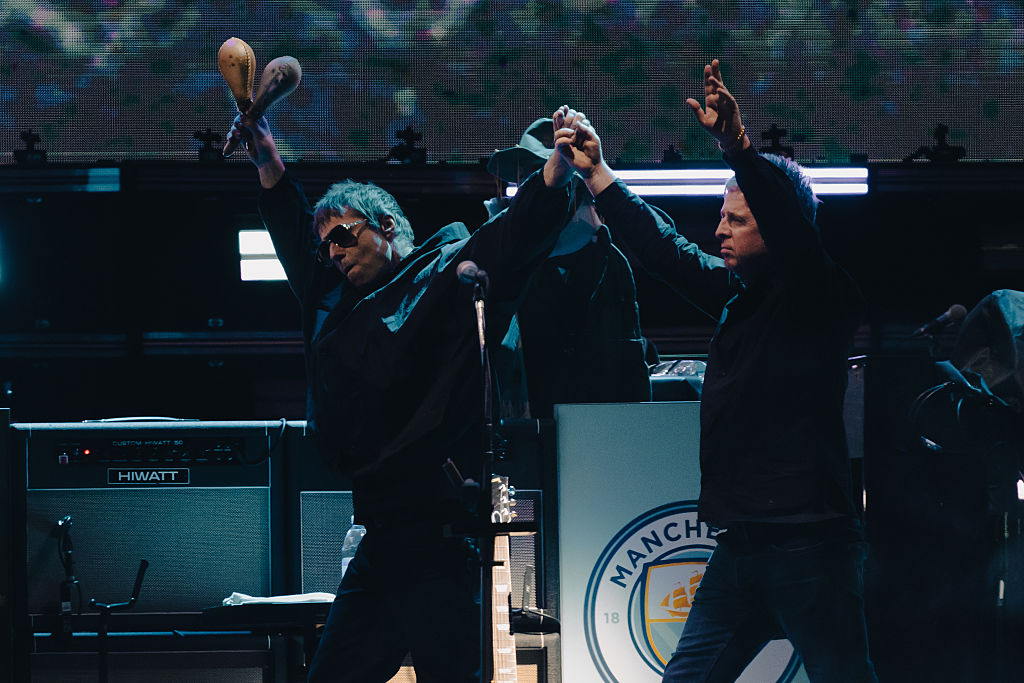

Audiences have not simply learned to tolerate the Gallagher brothers’ preening self-admiration; they have become enamored by it. (Chris Putnam / Future Publishing via Getty Images)

“What a stadium, man,” Liam Gallagher shouted at the audience, just over thirty-seven minutes into Oasis’s first of two sold-out shows at MetLife Stadium in East Rutherford, New Jersey — an 82,500-seater venue. “Nearly as big as my house.”

If there’d been any doubt, Oasis’s unmitigated swagger and trademark self-regard were clearly back. With recent stops in South Korea, Japan, and Australia, plus several more coming up in South America, their Live ’25 tour — the band’s first since breaking up in 2009 — has been a euphoric success. Leaving little to chance, it has also resulted in few surprises, whether capacity crowds (despite costly dynamic ticket pricing), visible onstage warmth between the oft-tempestuous Gallagher brothers, or charismatic setlists that have dwelled on the band’s canonical first two albums, Definitely Maybe (1994) and (What’s the Story) Morning Glory? (1995).

What has been surprising is the ecstatic reception the band has received, especially in the United States. While British listeners briskly institutionalized Oasis, reflected by their historic shows at the Knebworth Festival in 1996 only two years after its debut LP, they had a more polarizing effect on American audiences during the 1990s. Their brash self-proclamation about being bigger than the Beatles caused distaste at a time when crass commercialism proved divisive among musicians and audiences on the independent music scene.

Liam Gallagher confronted this past ambivalence in East Rutherford. “We love coming here. . . . We’ve even got one of your guys on the drums” [in reference to Joey Waronker, currently a touring member of Oasis]. “We love coming here,” he repeated later, “but what we didn’t like is being told . . . you gotta play the game, kids. . . . You don’t have to play the fucking game.”

If Oasis’s music and attitude hasn’t changed, the world has. Audiences have not simply learned to tolerate the Gallagher brothers’ preening self-admiration; they have become enamored by it. Their Northern English humor is better understood, their naked ambition more forgivable. Certainly, a heavy dose of nostalgia has figured into the tour’s success — ’90s musical acts like Pulp, Stereolab, and Pavement have also recently returned to acclaim. Yet nostalgia can mean many things. The populist appeal of Oasis that was once specific to Britain and their hometown of Manchester has intersected with the current global populist moment in unanticipated ways.

The world has seemingly caught up to Oasis. The band’s hard-edged, aspirational songs like “Rock ‘n’ Roll Star,” “Supersonic,” and “Live Forever” resonate once more, though for reasons they couldn’t have foreseen. Oasis’s return reveals the long-standing paradoxes of the Mancunian act, providing a soundtrack for the unreconciled contradictions of our present moment.

There Is No Easy Way Out

The populist character of Oasis forms a central thesis of Alex Niven’s excellent account of the band, Definitely Maybe (2014), part of Bloomsbury’s album-focused 33 1/3 series. Like other iconic groups, Oasis emerged amid a conjuncture of different, though related, trends that enabled their success. Along with acts like Blur, Elastica, and the Verve, Oasis was integral to the Britpop scene and the Cool Britannia moment of the mid- to late 1990s. More deeply, however, they evinced economic and political trends in Britain that were reshaping the underground musical landscape and its commercialization from the 1980s onward.

As Niven writes, Definitely Maybe is “an album defined by the claustrophobia of the decaying city in which it was imagined.” The city in question is Manchester, where the Gallagher brothers grew up on a council estate and which, along with its outer boroughs, had already produced influential predecessors like Joy Division, the Smiths, and the Fall, among many notable artists. It is also the city at the heart of Friedrich Engels’s 1844 study, The Condition of the Working Class in England. All that is to say that the Gallaghers grew up within two interrelated histories that fundamentally informed their worldview.

Equally significant, they both came of age in the Thatcherite Britain of the 1980s — Noel was born in 1967 and Liam in 1972 — with Noel later recalling his weekly trips with their dad to collect unemployment benefits (dole payments) from the local welfare office. This working-class milieu mimicked those elsewhere in the world, such as the Pacific Northwest, where figures like Kurt Cobain similarly encountered limited opportunities due to the parallel consequences of Reaganism. The coiled energy of bands like Nirvana and Oasis betrayed an emergent class rage that surfaced as an effect of these governments’ policies. Yet they also exhibited a tension between despair and aspiration that revealed a resistance to that era’s political conservatism while acceding to its individualist understanding of success.

Niven draws a further comparison between Oasis and the hip-hop of the time. Starting in the late 1980s, rap music took a decisive turn to sampling soul and R&B records from the 1960s and 1970s, as witnessed in groundbreaking LPs by De La Soul, A Tribe Called Quest, and Beastie Boys — a resourceful, bricolage technique that came to dominate the genre. Both Gallagher brothers went through a hip-hop phase (albeit briefly) with Noel, having seen Public Enemy perform in Manchester, calling them inspirational.

Hip-hop was certainly another response to Reaganism. More to the point is the resemblance of artistic method between Oasis and their rap artist peers. Both took a scavenger approach to the past to salvage material that could be reutilized in the present, treating the recordings and musical heritage of those who preceded them as a kind of public commons. The critical accusation that Oasis was derivative of the Rolling Stones, T. Rex, and especially the Beatles has never really hit hard, largely because Oasis, like their hip-hop counterparts, have been transparent about their muses and adoration for them.

Oasis furthermore emulated the local style of their time. In addition to the heavy, high-volume sound of grunge, they retained elements of Britain’s like-minded shoegaze scene that extensively used effects pedals to create immersive soundscapes of saturated reverb. Oasis signed to Creation Records, home to prominent shoegaze outfits like Slowdive and My Bloody Valentine as well as important precursors like the Jesus and Mary Chain, who also experimented with distortion. Niven highlights how the same sound engineer, Anjali Dutt, was behind the boards for both Definitely Maybe and My Bloody Valentine’s classic Loveless (1991), widely considered the epitome of its genre.

Nonetheless, Oasis went to surpass these early comparisons. Crafting their own identity, the Gallaghers adopted a transfixing public image in addition to their music, involving loutish behavior, football shirts and bucket hats, and, not least, displays of friction (at times staged) between the coolheaded Noel and hotheaded Liam. This spectacle of unreconstructed masculinity that became known as “laddism” formed part of a broader cultural drift spanning from the delinquents of Irvine Welsh’s Trainspotting (1993) and its film adaptation by Danny Boyle to Martin Amis’s much later novel, Lionel Asbo: State of England (2012).

An ugliness accompanied this cultivated unruliness. In a manner that came across as racist to many, Noel criticized the choice of Jay-Z as a headliner for the Glastonbury Festival in 2008, saying hip-hop had no place at the event. In response, Jay-Z famously trolled Gallagher by covering “Wonderwall” at the start of his set. Mark Fisher would later disparage Oasis and the Britpop scene for promoting an uncomplicated and exclusively white version of Britishness that neglected the innovations of musicians like the trip-hop visionary Tricky, who was recording during the same period.

The music of Oasis would also suffer. Global success led them beyond their Mancunian origins, cutting them off from the wellspring of their best music. “Everything good about Definitely Maybe — its dreams of escape, its sense of solidarity, its rare freedom with borrowed materials – gets its validity from this backdrop,” Niven writes sympathetically. “When this anchoring later disappeared, Oasis would lose their orientation quite spectacularly.”

Things They’ll Never See

“Nowadays, Oasis are one of those bands who are mostly popularly loved, mostly critically scorned,” Niven begins in Definitely Maybe. Dated to 2014, this judgment has arguably been surpassed by a new critical consensus with many commentators softening their views following this year’s reunion tour. For longtime fans, however, Live ’25 has been nothing less than cathartic.

Clint Boon of Inspiral Carpets, for whom Noel once served as a roadie, described the mood in Manchester for Oasis’s five shows this past July as being “like the end of World War II.” With more restraint, though no less enthusiastic, Irvine Welsh has said the tour is “what we’ve needed” in terms of bringing a collective feeling of joy for people at a time when Britain and the world have been at a crossroads. Another conjuncture of political, economic, and cultural trends, transatlantic and otherwise, have marked the band’s return.

Oasis has never made any pretenses about being politically outspoken — or especially astute when called upon to do so. As Niven recounts, the Gallaghers were “huge fans” of Tony Blair, who quickly became misguided conscripts for popularizing his New Labour project. More recently, Noel has made occasional, mild-mannered remarks about class and opportunity, decrying how expensive it is to start a band these days.

Yet it is precisely the band’s apolitical nature that has made its tour a problematic reprieve for many. Unlike Brian Eno’s Together for Palestine benefit concert or the public stances of individual acts like Kneecap or Massive Attack, the genocide in Gaza has not been a topic at their shows, let alone crackdowns on free speech and immigration. Nostalgia means not only indulging your past but escaping the difficulties of the present.

Nostalgia is also an opportunity to rebuild mythologies. Unlike U2, an older peer who went on to deconstruct the myths of the American West and post–Cold War Berlin on The Joshua Tree (1987) and Achtung Baby (1991), Oasis has never demonstrated an interest beyond themselves. In some ways, this solipsism has served them well. Though often placed in competition with Blur, a more illuminating comparison is with Radiohead — at one time a politically high-minded band, wildly popular in the United States, that has since faced withering criticism for its hypocrisy vis-à-vis Israel.

With Live ’25, Oasis has remobilized their own mythology to reconceal a contradiction they have long harbored. Though the Gallaghers suffered the effects of Thatcherism during their childhood and young adult years, they have equally exemplified Thatcherism’s appeal to individual self-making and self-realization. While numerous British acts, whether Black Sabbath or the Beatles, also moved beyond their working-class roots — as did many of Oasis’s hip-hop contemporaries in the US — it is difficult not to observe this irony. Oasis may be Thatcherism’s greatest cultural success story.

That Oasis has so absconded from the politics of their working-class roots relates to the political zeitgeist of our current moment, explaining why the band resonates again today in the way they have. More than simple ’90s nostalgia or the (arguably) manosphere-adjacent qualities of Oasis’s laddism, the return of the Gallagher brothers has fortuitously coincided with an emergent, backward-looking populism on both sides of the Atlantic — a response to intensifying economic inequalities, but not by means of working-class solidarity.

“The core of Oasis’s identity was populism,” Niven writes. “Perhaps more than anything else, their rise in the mid-nineties represented the unleashing of a form of populist idealism with strong roots in the experience of working-class culture in the late twentieth century.” Yet this promise of articulating something greater and more collective faded as their recording career progressed. Their staged populism became more lucrative than liberating, leaving any meaningful political messaging or substance aside. Oasis is emblematic of today’s broader abandonment of working-class politics and its self-defeating limits.

Though Live ’25 has restored a semblance of collective feeling for some, Oasis’s return serves as a reminder of their shortcomings and how their cultural and political turn during the 1990s fundamentally affected their creative direction and longevity. Ever concerned with the matter of greatness, Noel and Liam Gallagher curtailed the full extent of this possibility, despite the accomplishment of their first two albums. As warm and welcoming as nostalgia might be, it cannot repair that missed opportunity.