Can Canada’s NDP Step Back From the Brink of Electoral Ruin?

The leadership race in Canada’s New Democratic Party has exposed fractures between workers and professionals and between leader-driven branding and party democracy. Its survival as a serious left-wing force depends on successfully navigating these divides.

If NDP leadership candidates are serious about reconnecting with workers and getting them to the polls, public ownership and economic inequality must remain front and center. (ndpcanada / Instagram)

In March, Canada’s New Democratic Party (NDP) will elect a new leader. This April, the federal party suffered its worst election showing ever, winning a mere seven seats. Leader Jagmeet Singh promptly resigned. Five candidates have registered in the race to replace him, including current member of parliament (MP) Heather McPherson, activist and filmmaker Avi Lewis, union leader Rob Ashton, social worker and town councilor Tanille Johnston, and Tony McQuail, a farmer and former party candidate. Montreal activist Yves Engler is running but has yet to register with the party.

To get a sense of the state of the race to date and where it might be headed, Jacobin writers David Moscrop and Edgardo Sepulveda examine four aspects of the party and the leadership competition. They take up the historical context, how candidates are addressing environmental, economic, and industrial policy, the class and cultural dynamics at play, and the state of party democracy.

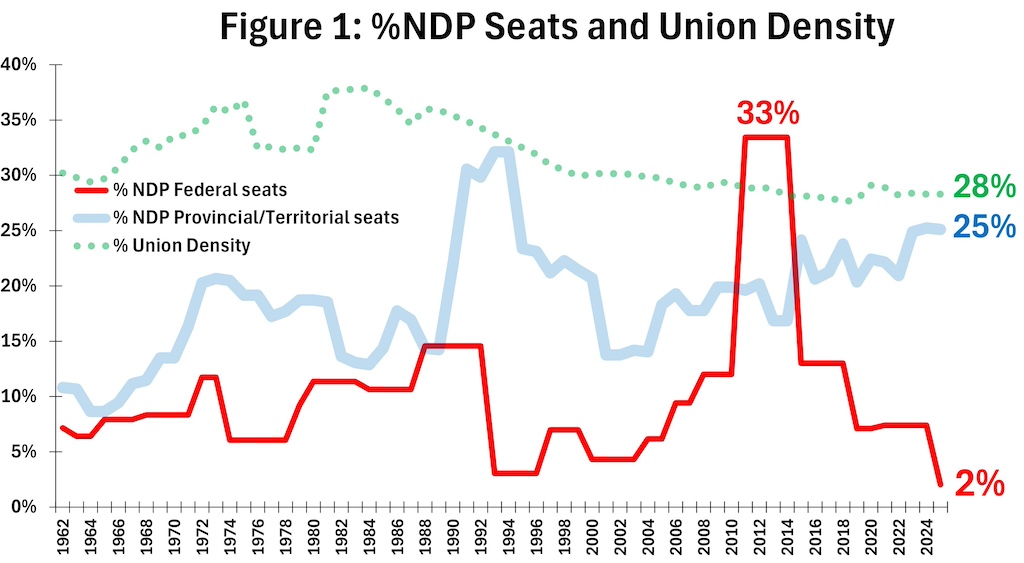

Edgardo Sepulveda: As someone who works with numbers, I compiled data from 1962, the year after the NDP’s founding, to track its electoral success as a percentage of seats in parliament. Figure 1 shows that its current seven seats represent only 2 percent of MPs in Ottawa.

Figure 1 also highlights two metrics that point to ongoing structural potential for social democracy in Canada. Across all provinces and territories, NDP caucuses account for 25 percent of legislative seats. Meanwhile, union membership remains robust by current standards at 28 percent, well above the 10 percent rate in the United States. The union connection is foundational; the NDP was cofounded by the national federation of unions and the NDP retains formal affiliation with the Canadian Labour Congress (CLC) and other labor organizations.

Yet figure 1 shows that since 1993 the federal NDP has generally fallen short of these two benchmarks, with the exception of the 2011–14 electoral surge. The core challenge for the federal party and those seeking to lead it is to translate provincial strength and active union support into federal gains. Attracting more union members and other workers to the NDP — a party historically anchored in the labor movement — will be essential to reviving its electoral prospects.

David Moscrop: Twice before, the NDP — or its precursor, the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) — was nearly blown off the electoral map, seemingly for good. In 1958, under Major James Coldwell, the CCF fell from twenty-five seats to eight; in 1993, under Audrey McLaughlin, the NDP won just nine. Each time, the party eventually returned to its historical average. Call it regression to the mean. But there is a real risk that the party system polarizes into a two-party contest between Liberal and Conservative, split over questions of affordability and over who is best suited to manage Donald Trump or whatever the US threat of the day may be.

The next NDP leader must offer voters a clear value proposition that sets the party apart while convincing them it can deliver on core concerns and the ground currently occupied by the two main parties. As pollster David Coletto has written, Ashton may pose a particular risk to the other parties because his explicit class politics speak directly to the precarity so many Canadians feel. At the very least, this suggests the NDP’s future, and electoral success, may run through unapologetic class politics.

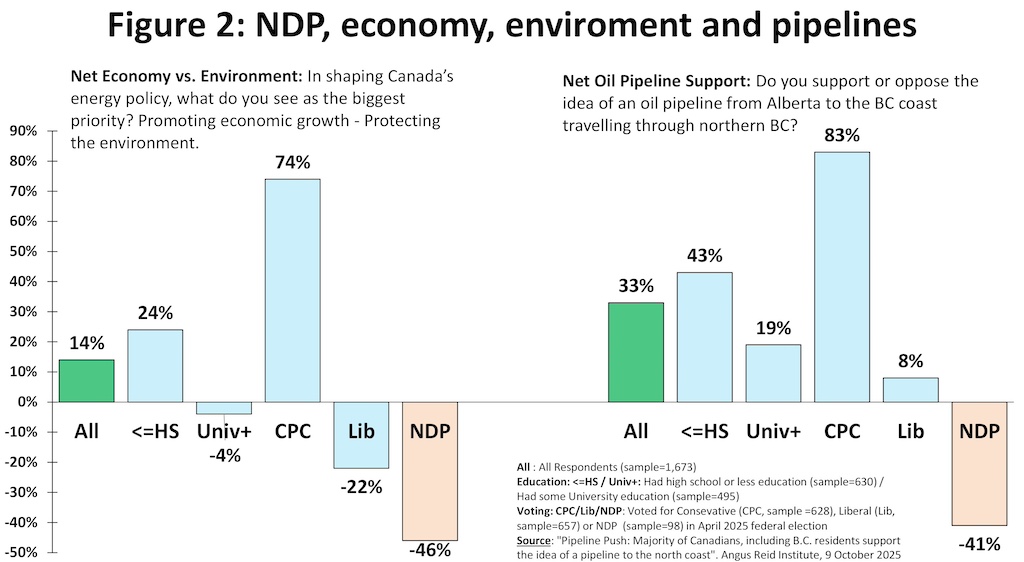

Edgardo Sepulveda: I have argued that the NDP is increasingly out of step with the working class, orienting itself instead toward professional-class preferences. This dealignment is especially visible in environment–economy debates. Polling shows that NDP voters’ views differ markedly from those of Canadians overall, and even more so from workers with only a high school education.

On the key question of whether to prioritize the economy or the environment, figure 2 shows that 14 percent of Canadians choose the economy, while 46 percent of NDP voters favor the environment — a gap that is even wider when comparing NDP voters to working-class high school graduates. The pattern is sharper still on pipeline development: there is an 84 percent gap between NDP voters and high school graduates on net support for more pipelines. In both instances NDP voters align more closely with university graduates.

While pipeline policy rightly involves indigenous consent and environmental safeguards, the underlying question remains whether voters support expanded oil and gas production. On this, the NDP consistently struggles to persuade working-class Canadians of its vision — not because workers reject environmental concerns, but because they experience the economy-environment trade-off as real and immediate. Yet in the face of this dealignment and electoral defeat, the responses from Lewis, McPherson and Ashton have been strikingly limited: the party need not have changed its “values” or policies, they argue, but simply communicate them more effectively.

This is rebranding, not renewal. The NDP faces a strategic choice: it can continue to promote the environmental preferences of its professional-class base or it can craft a credible program focused on improving material realities for its working-class base. Worker-driven industrial policy offers such a path — one that takes economic insecurity seriously without surrendering environmental goals.

David Moscrop: At the risk of oversimplifying the race, the top candidates do seem to fit distinct archetypes — or, more precisely, potential strategic paths for an NDP trying to recover from a devastating election. McPherson is both an insider and party elite, which isn’t inherently pejorative. She knows how to do House of Commons politics, though it remains unclear how strong her organizing skills are. She may be credible on infrastructure, though the details are still vague. The Lewis campaign, by contrast, appears to be looking to wedge McPherson on oil and gas, offering a coastal, urban, activist socialism of the sort the party has been associated with for some time now.

Ashton is running on full-bore, eat-the-rich class politics, while recognizing the environmental tension in a jobs!-jobs!-jobs! strategy in a resource-dependent country. He recently told me that he believes Canada can take on big infrastructure projects — “dams, nuclear plants, and geothermal projects” — that “meet the highest standards and fully respect Indigenous rights, including free, prior, and informed consent.” He also supports growing a “value-added economy.” Fine ideas all around, but harder to execute than to articulate. And in the end, you’re judged on the execution.

Edgardo Sepulveda: When asked why he wanted to be leader, Ashton said that he wanted Canadians to be able to take a vacation and enjoy a steak for dinner. The idea of everyday abundance for the working class is hardly new; it animated much of the postwar social democratic project.

Ashton has a point. Many Canadians report eating less beef, partly due to cost. Based on Statistics Canada food price and earnings data, figure 3 shows that since 2019, the average wage earner now has to work 36 percent more — an extra eleven minutes — to purchase a kilogram of sirloin steak. For minimum-wage workers, it is an additional twenty-six minutes; for the top 1 percent of earners, just half a minute.

With affordability dominating political discourse, figure 3 shows why Lewis’s “public grocer” proposal, which promises to lower food prices, is attracting attention — and why Ashton’s class-based rhetoric resonates. It speaks directly to the economic inequality on full display in the data.

If NDP leadership candidates are serious about reconnecting with workers and getting them to the polls, public ownership and economic inequality must remain front and center. This means avoiding messaging strategies and cultural positioning that too often preoccupy parts of the Left — including symbolic debates over consumer choices.

David Moscrop: By now it may appear that Ashton is my preferred candidate — and he is. When I talked to him about the perceived split between class and identitarian politics, he cited an old union organizing mantra: division is a tool of the boss. Many will recall the old line that “they” want you fighting a culture war so you don’t fight a class war. The fact is the Left fights plenty of its own culture wars without prompting from anyone else. And yet, a left movement has to be a unified movement, even as it recognizes that performative politics is a dead end.

When McPherson talks about ending “purity tests,” a rather benign statement when read in good faith, she is touching on the same sentiment. And when Lewis emphasizes, say, public ownership of grocery stores to compete with the oligopolists, he, too, is trying to shift the terms and focus of debate. So far, it seems that the candidates aren’t taking the culture war bait, which is a testament to their commitment to doing politics successfully rather than treating the leadership contest like a graduate school seminar.

Edgardo Sepulveda: Three issues have dominated the debate over the NDP leadership contest rules: the length of the campaign, the high $100,000 entry fee, and the strategically delayed registration of Engler. Yet these controversies obscure a broader structural problem: as the party becomes increasingly leader-centric, the contest system incentivizes leader-driven short-term gains rather than genuine long-term party building.

NDP leadership contests are designed to measure candidate popularity by signing up as many new members as possible and fundraising from them. In a leader-centric model, these metrics are assumed to predict future electoral success.

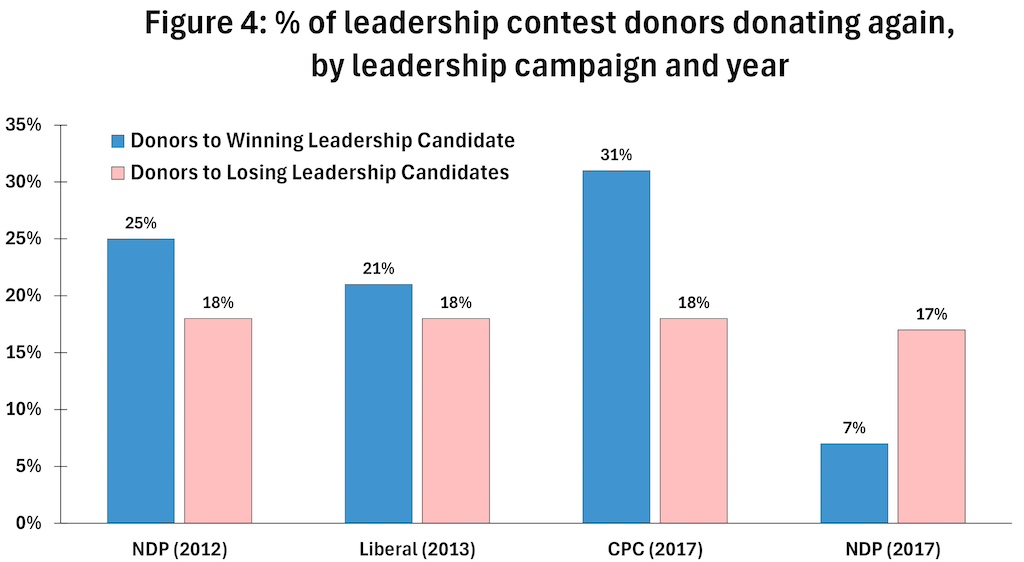

The 2017 race illustrates this dynamic. The NDP began with 41,000 members and ended with 124,000, with the winner signing up 47,000 new members and prevailing with 35,266 votes — most from new, rather than existing members. Despite the influx, experience suggests most of these members did not remain active.

Donor retention data is even more revealing. Figure 4 shows only 7 percent of members who donated to the winner’s 2017 campaign contributed to the party the following year, compared to an average of 26 percent for other leadership contests and 17 percent for donors to losing candidates in 2017.

Under a leader-centric model, designing a contest around recruiting new members and fundraising makes internal sense. The problem is that in 2017 this short-term leader-driven model did not result in long-term party strength. Whether that will change in 2026 remains to be seen. If it does not, the NDP should redesign its leadership contest to reflect a less leader-centric approach.

David Moscrop: I’m most interested in what happens next — after the leadership contest. Every candidate talks about party democracy and mobilizing the grassroots because it’s cheap and easy. Over the past few decades, the NDP has “professionalized” and centralized — a trend that began in earnest in the Jack Layton years and never stopped. This mirrors developments in other parties that began even earlier as well as a broader tendency in the state itself to centralize power that stretches back to the 1960s.

It makes a certain sense to centralize and professionalize, since parties need to be coherent and must move fast both strategically and substantively on the evolving issues of the day. Moreover, someone needs to be clearly accountable. But a left-wing party that ostensibly exists for workers must be connected to its grassroots and supported by internal and external movement politics, the latter of which is also well placed to challenge and provoke the party, and to keep it honest.

NDP leadership voters deserve to hear more from candidates about how they intend to run the party — the governance particulars. How much freedom, and how many funds, will they leave to electoral district associations? How often will they listen to convention delegates, and will they respect resolutions passed at those conventions? Will they even permit controversial resolutions to reach the floor? In short: How internally democratic do these candidates want the New Democratic Party to be? And if they win, will they keep singing the same tune?