For Karl Marx, Human Flourishing Is Inherently Social

Central to Karl Marx’s vision of the good society is the idea that people fully flourish only in meeting the needs of others.

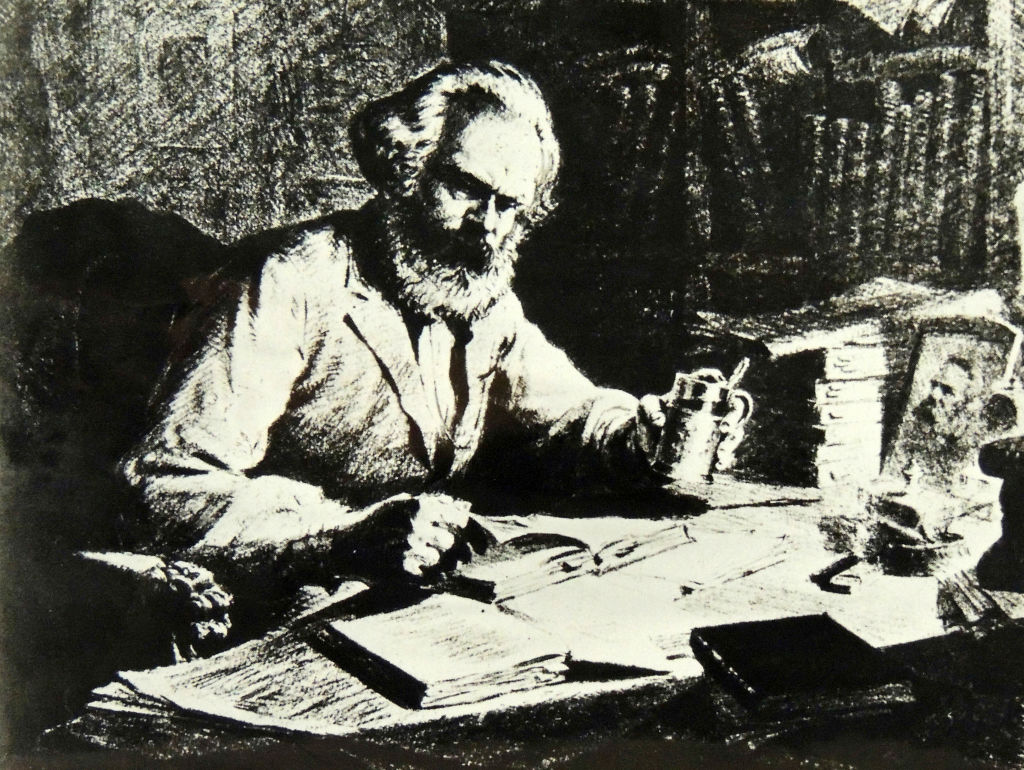

Karl Marx’s vision of the good society is often dismissed as unrealistic, said to depend on limitless abundance and no need for people to perform different kinds of work. These objections are based on a misinterpretation of his view. (Universal History Archive / Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

Much contemporary left thought focuses on what is wrong with capitalism. Is capitalism bad because of its unjust distributive outcomes? Or is it bad because workers are dominated, subjected to arbitrary power? Or does the badness of capitalism have to do with the opacity of the market and the way it prevents valuable forms of collective agency?

While this debate about what is wrong or unjust in capitalism is important, the Left also needs to articulate a positive vision of a good society that could replace capitalism. After all, simply highlighting the problems of capitalism is unlikely to be enough to persuade people to embrace socialism. And while Karl Marx wrote that it was not for him to write “recipes for the cook-shops of the future,” “unless we write recipes for future kitchens, there’s no reason to think we’ll get food we like,” as G. A. Cohen put it.

In my forthcoming book, Flourishing Together: Karl Marx’s Vision of the Good Society, I put forward a novel interpretation of Marx’s vision of the good society. This interpretation defends the centrality of personal development and satisfying the needs of others to human flourishing. On this view, we realize ourselves through providing others with the goods and services others need for their flourishing. I argue that this interpretation is appealing, and that it could provide the Left with an attractive account of an alternative to capitalism.

However, Marx’s vision of the good society is often thought to be based on unrealistic assumptions, such as limitless abundance or an overcoming of the division of labor. My contention is that these assumptions are based on a misinterpretation of Marx’s position. To understand why Marx’s vision of the good society has been misinterpreted, we need to first understand the philosophical roots of this view.

Cohen’s Interpretation

In political philosophy, the prevailing interpretation of Marx’s vision of the good society owes much to the work of G. A. Cohen. A founding figure of Analytical Marxism, Cohen was the author of the brilliant book Karl Marx’s Theory of History: A Defence, as well as trenchant critiques of the libertarianism of Robert Nozick and the liberal egalitarianism of Ronald Dworkin and John Rawls. As one of the leading political philosophers of his generation, Cohen’s interpretation of Marx has had a lasting and widespread influence. Yet for all Cohen’s brilliance, his interpretation of Marx’s vision of the good society is seriously flawed.

In Cohen’s interpretation of Marx, the chief good of communism is that it will enable self-realization. On this, we agree. But Cohen interprets Marxian self-realization in work in a starkly individualistic way. Specifically, in his view self-realization involves the full and free development of the capacities of individuals and does not have to involve satisfying the needs of others.

This view of self-realization is social in that people need others’ goods and services to pursue their self-realization. However, it is only social in a very weak sense, because doing things for other people is not itself part of self-realization. It follows that if one could somehow obtain the goods one needs for one’s self-realization without others — suppose God rains manna from heaven — nothing would be lost.

Cohen illustrates this idea via an analogy with a jazz band:

One way of picturing life under communism, as Marx conceived it, is to imagine a jazz band each player in which seeks his own fulfilment as a musician. Though basically interested in his own fulfilment, and not in that of the band as a whole, or of his fellow musicians taken severally, he nevertheless fulfils himself only to the extent that each of the others also does so, and the same holds for each of them.

Cohen concludes: “So, as I understand Marx’s communism, it is a concert of mutually supporting self-fulfilments in which no one takes promoting the fulfilment of others as any kind of obligation.”

What makes this society — in which everyone can produce as they please and take whatever they may want from the common stock of resources — possible? If people produce as they please, how can we ensure that needs are met? Won’t there be some jobs that we have to do that people won’t find fulfilling? And won’t we need some principles to govern the distribution of resources? In reply, Cohen argues that Marx appeals to a “technological fix.” According to Cohen’s interpretation of Marx,

a plenary abundance ensures extensive compatibility among the material interests of differently endowed people: that abundance eliminates the problem of justice, the need to get what at whose expense, and a fortiori, the need to implement any such decisions by force.

In Cohen’s view, limitless abundance represents a sort of deus ex machina: it enables Marx to sidestep difficult questions about the coordination of work, economic justice, and even the need for the state. However, this sidestepping is illegitimate because it ignores ecological constraints: “It is no longer realistic to think about the material situation of humanity in that pre-green fashion.” Thus Cohen argues that socialists should drop Marx’s individualistic vision of the good society, in which people produce and consume as they please in conditions of limitless plenty, in favor of a moral vision of socialism, in which everyone has a duty to work in their most productive occupation. In other words, Cohen thinks we should swap Marx’s technological utopianism for a utopianism about human nature.

I agree with Cohen’s criticisms of the “technological fix.” But in my view, they are not problems for Marx but for Cohen’s interpretation of him. There is an alternative, appealing interpretation that does not fall foul of Cohen’s criticism.

Flourishing Together

In Flourishing Together, I argue that Marx has a very different vision of the good society than the one Cohen saddles him with. I agree with Cohen that one of the major goods of communism is self-realization. However, I understand self-realization in a very different way.

My view draws especially on Marx’s account of what it would be like if we “produced as human beings” in his 1844 text “Comments on James Mill.” The crux of the idea is simple. People do not realize themselves merely by exercising and developing their powers; they realize themselves through exercising and developing those powers in ways that provide others with the goods and services those others need to pursue their flourishing. So, if we go back to the example of the jazz band, then while it is true that each player’s fulfilment as a musician partly consists in developing their talents, a central part also consists in utilizing those talents to provide their fellow musicians with the conditions for their self-realization, and in contributing, alongside their fellow musicians, to the creation of music that satisfies the needs of their audience.

This view relies on a particular understanding of human nature and motivation. It rejects the view of human beings as homo economicus, in which each seeks their own narrow self-interest. Yet it is not an austere vision of self-denial either; communism, Marx wrote, is not the “love-imbued opposite of selfishness.” It rather sees people as realizing themselves through others, by helping other people satisfy their needs.

This provides a very different, and, to my mind, much more appealing account of Marx’s vision of the good society than the one Cohen attributes to him. To illustrate, I note three implications of this vision.

First, this vision does not require limitless abundance. People realize themselves through providing others with the goods and services that those others need for their flourishing. This view requires a certain level of technological development to elevate work from an activity of mere survival and to ensure that a rich array of needs can be met. But abundance need not be limitless. In fact, limitless abundance represents a problem. If God were to rain manna from heaven, such that everyone’s needs were met without work, self-realization would be undermined. Producers could not experience the fulfillment of satisfying another’s needs.

Second, this vision does not require abolishing the division of labor. In fact, the view requires a division of labor, because once we think that self-realization in work involves meeting others’ needs, we will need a division of labor to coordinate responsibilities between workers to ensure that their work actually does that. Absent a division of labor, our ends would be frustrated.

Third, this vision suggests that a post-work society represents a bleak prospect. We have a need to develop our powers via meeting the needs of others. A scenario in which work was no longer required — such that there was no need for doctors, builders, journalists, teachers, or indeed jazz musicians — does not represent a great boon for human freedom and well-being. It would be one in which a vital component of human flourishing would be thwarted.

A Social Vision of the Good Society

In conclusion, let me return to Cohen. He argues that Marx’s vision of communism requires limitless abundance. However, for ecological reasons, limitless abundance is untenable. Thus, the only hope for communism is if people serve others out of duty. This was not Marx’s view of what makes communism possible, but it is the view Cohen thought Marxists ought to adopt — because the loss of faith in limitless abundance means it is the only game in town.

Yet his conclusion is too quick, for there is an alternative to both the individualistic vision of communism he attributes to Marx and the rather austere vision of socialism that Cohen himself adopts. At the heart of this idea is the thought that we realize ourselves through meeting the needs of others. This is a vision of communism that puts self-realization and solidarity with others front and center. This was Marx’s vision of the good society, and it has much to offer the Left today.