The Defeat of European Socialism Was Far From Inevitable

Contrary to popular belief, the 1970s was a period in which the European left was at its strongest. Unions were powerful, and socialists felt confident that the changing economy could benefit them. So why was the Left defeated a decade later?

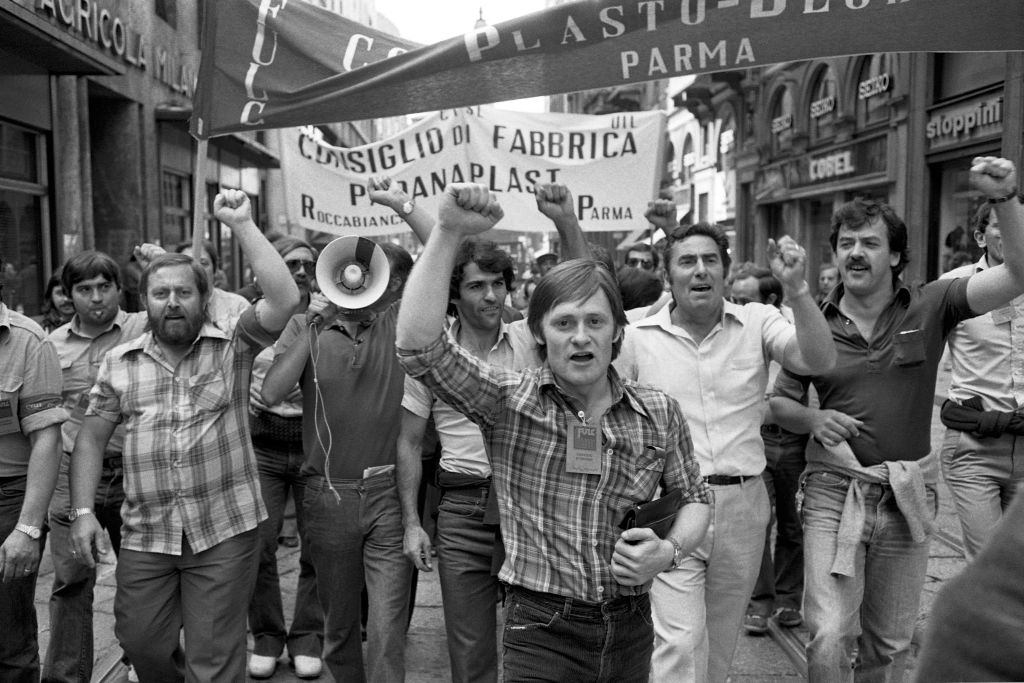

Trade unionists marching during a demonstration in Milan, Italy, on May 4, 1979. (Edoardo Fornaciari / Getty Images)

- Interview by

- Ashok Kumar

One of the dominant ways of understanding the history of European socialism in the second half of the twentieth century is as one of decline. According to this account, leftist parties, faced with globalization, deindustrialization, and cultural and ethnic shifts in the composition of the working class, were disorientated and unable to respond. In his book The Halted March of the European Left, Matt Myers, a lecturer in history at the University of Oxford, argues that the 1970s were far more complicated than their interpreters make out.

Far from being a period characterized by socialist retreat, the Left was at its strongest in the 1970s, and workers, unions, and their leadership felt confident that they knew how to navigate the changing economic landscape. Myers spoke to Jacobin about what this history, based on years of archival research in England, France, and Italy, can teach us about the real causes of the defeat of the Left and what could be done to renew it today.

How did you come to write your book The Halted March of the European Left?

I came to write the book after being frustrated by an overarching narrative related to the decline of the working class in European history. This narrative claimed that there were two key shifts, one structural and the other cultural, which inevitably marginalized parties long associated with workers after the mid-twentieth century. The first shift was caused by deindustrialization, which it was claimed abolished the factory-based working class. The second was the result of the rise of new values of autonomy and consumerism, which fragmented the Left’s egalitarian and collectivist culture.

In brief, the rise of a service-based and globalized economy restructured class while permissiveness replaced materialist solidarity. It was assumed that educated white-collar professionals and de-classed identity groups forced the Left to adapt to their concerns. The working class comes out the victim with no agency for itself.

I felt that there was something missing in this narrative, whose major proponent was, of course, Eric Hobsbawm. He made an eloquent case in his 1978 essay, “The Forward March of Labour Halted?,” and classic history of the twentieth century, The Age of Extremes. But I sensed that his way of thinking had not fully explained what had happened during the 1970s.

Then, when I got into the archives and read the actual documents, Hobsbawm’s declinist account seemed particularly limited. I was confronted by a strong, dynamic, and cerebral labor movement and a changing, rather than disappearing, working class. Many at the time Hobsbawm delivered his “The Forward March of Labour Halted?” lecture, from Margaret Thatcher to the lowliest factory manager, didn’t think that socialism was on the back foot but rather the opposite. Trade unions peaked in Europe at the end of the 1970s. In Britain, their membership had never been higher in 1979, and during that period we also see peaks in wealth equality, welfare spending, and workers’ rights.

The archives I consulted in Britain, France, and Italy all suggested that the declinist narrative was tied to retrospective projections rather than being full reflections of what was actually happening. I have tried with my book to center the accounts of workers and others working politically close to the ground. This is an attempt to move beyond what has become a well-established disconnect between histories of the Left and histories of labor, which are too often developed on parallel tracks. The former is conceived separately to the history of workers’ movements and the latter neglects the inner life of parties. My book attempts to reconnect political history to working-class history.

Your book argues that the European left’s historic advance was halted. What were the key moments when this forward march stalled, and was it inevitable?

The central claim is that retrospective theories of decline of the twentieth-century left have not yet come to terms with the 1970s as a period of working-class empowerment. During that decade, organized labor was very strong. Parties committed to representing the working class were in power across the continent. Social democratic parties ruled in Britain, Belgium, Holland, Norway, Denmark, West Germany, Austria, Sweden, and Finland from 1974 to 1975. Communist parties expanded rapidly and achieved electoral breakthroughs.

What I was trying to explain was a paradox. Why had growing working-class influence coincided with the belief among a number of intelligent people on the Left that labor’s forward march had been halted? Many workers believed that their movement hadn’t been halted, and their actions proved this. Likewise, many of the workers’ adversaries, in particular conservative forces, didn’t believe that labor had already been defeated, or even halted, and acted upon these assumptions.

There was a critical checking of momentum toward the end of the 1970s, but this happens during a period of epochal social, political, and ideological conflict. So rather than being prefigured or predetermined by earlier developments, the 1970s seemed far more open at the time. Retrospectively locating the reasons for the decline of class politics in the 1950s and ’60s — as thinkers ranging from Hobsbawm to Tony Judt, François Furet, and Seymour Lipset had done — underestimated the significance of that decade.

And so what were the structural factors behind this decline and what were the subjective ones?

Well, the dominant explanation of labor’s decline has been that a changing social structure and cultural references undermined working-class institutions behind their backs. However, I found that three different West European movements were aware of these processes as they were occurring. And many, including their leaderships and liberal adversaries, thought that those changes were having the opposite impact on the Left’s prospects. They actually thought that changes to the structure of the economy and popular world views were invigorating working-class politics.

So I don’t think that one can straightforwardly say that deindustrialization and cultural diversification led to the decline of the Left because in fact, these processes were already well underway in Europe. Why, then, does the Left expand its influence during the 1970s? Why, then, does working-class politics seem to be renewing? Supporters of the declinist narrative might say this merely represents the death rattle of a group of actors in a defensive and ultimately doomed posture.

No one would suggest that the structural factors of technological change or cultural shifts hadn’t raised significant challenges. However, to see this as a death rattle is to foreclose the idea that the specific political response to these changes also had consequences. This is not to say the political decisions on their own are decisive, but, as part of reconciling political and social history, I want to recognize that the structural and the subjective play interrelated roles.

In terms of being more specific about subjective factors, I came to realize that these were partly linked to new kinds of workers becoming political actors. A new working-class generation, which had emerged from the margins of the old working class, kept appearing in all the material I was reading. An overly narrow conception of that class, bounded by a specific age, race/citizenship, and gender profile, had been left out of this part of the story.

By the margins I mean those at the bottom of the Fordist division of labor, which in Europe during the 1970s generally meant women, racialized minorities, and the young, as well as those educated white-collar workers in technical, research, or supervisory grades at the top. Workers at both margins were joining parties and unions and engaging in what you might call “traditional” forms of class struggle: striking, refusing to cross picket lines, and joining parties and trade unions. The working class during the 1970s was looking and sounding different from before. And many on the Left, not only its activists, thought that this expansion of the working class was a positive and hopeful development.

The French Communist Party leadership in 1979 claimed that “the current technological revolution is ushering in a new era of productive forces. . . . Socialism is no longer a utopia. The conditions are emerging for humanity to leave its prehistory.” The head of the Italian Communists in Turin argued in 1980 that “today the struggle is taking place between a stronger working class with greater ties to other social classes, both more in control of its elementary needs and more demanding, and a class of industrialists much more subjected to the crisis and less capable of responding strategically.” The Left organized and disseminated opinion polling that suggested that their members, supporters, and voters agreed with this kind of prognosis.

There’s a critique of both social democracy and the radical left in what you’re saying. Who, in your view, bears more responsibility for the Left’s decline: parties that abandoned class politics or insurgent left movements failing to build durable power?

I would first start by saying that the Left’s fate in the 1970s was determined by a complex interaction of factors. But the first one to note is the backlash, not primarily or predominantly driven from its own side of politics, which begins in the factory before expanding to the whole of society. Reclaiming the initiative after major workers’ victories between 1968 and 1972, during unprecedented strike waves in Britain, France, and Italy, took a decade to achieve. Yet, as I show in in my book, historians have paid little attention to the epochal strikebreaking movements that occurred at the end of the decade. These were also unprecedented in size and complexity and explicitly sought to halt and roll back movements led by immigrant workers.

I try to show that the Left in Europe, both the radical and the institutional, was caught in a bind by the strategies of employers, conservative political forces, and elements of the state. In both cases they were forced to choose between unappealing options. Perhaps the most pressing was to radicalize or moderate their strategies. They’re of course not the only agents in this story, and the Left is not in total control of the situation. But the ultimate outcome of the decisions taken at this critical moment was the evacuation of the working class from left structures and a weakening of labor more broadly.

There are clashes over what to do about economic restructuring and automation, participation in management structures and government, and media and communication technologies. An older generation of self-educated industrial worker activists rub up against a younger generation of educated, often white-collar members, each with different views on priorities and conduct. I mainly focus on the main electoral parties of the Left because they were the main organizations that workers joined and voted for at the time, and the ones that shaped how millions of people thought about the world. The radical left had sparser influence even if they suffered a broadly similar outcome.

In brief, the West European left went into decline not because of an unstoppable neoliberalism and a weakened manufacturing-based economy, but because it failed to recognize and mobilize new constituencies of workers, including migrants and women, and instead embraced a kind of “third way” social capitalism.

Is there a tradition on the Left of blaming secular stagnation — the slowdown and, in some cases, flattening of the rate of profit from the late 1960s to the present — for the defeat of the socialist left?

What I was trying to do in the book was to explain why the Left in Europe, which I think has a slightly different history to that of the United States and Japan, seems to advance strongly until the early 1980s. This advance occurs even as global productive capacity expands and interfirm competition, rising energy and financial costs, and other factors impinged on profits. I wanted to understand why the working class was taken so seriously during a period of economic stagnation.

It is of course very important to take into account the global context. But the more research I did, the harder I found it to draw easy political conclusions from these changes. There didn’t seem to be a simple relationship between the transformation of global capitalism and their effects on the Left. Organized labor was on the offensive rather than the defensive during the 1970s. For a time, it seemed to be widening its reach and radicalizing its demands, rather than narrowing and moderating.

The workers’ movement was beginning to take seriously the diversity of the working class, often because they were forced to do so by women, black and immigrant, and young workers who had recently joined the ranks. I did not see much evidence of secular stagnation restricting their sense of possibility. Managers and employers in manufacturing industries, as well as conservative forces, felt they had recovered their sense of confidence and authority only after winning a series of high-stakes conflicts in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

And how much can we extrapolate from the experiences of Italy, France, and Britain to the contemporary Anglo-American left?

The 1970s and the British, French, and Italian cases are to some extent particular. The scale and depth of class conflict was in advance of what has characterized social and political developments in the West over the past ten years. But I do think we can say that there are some resonances between these two periods. Both are characterized by economic crisis, structural change, and mass mobilizations. Then, like now, the meaning of the working class is a subject of debate and a subject of change. Back then an older conception of the working class was being tested by the entry of new workers into the Left’s political coalition.

Today a diverse new generation has also faced disempowerment by the Left. Workers at the margins during the 1970s destabilized the Left because they brought with them new forms of conceiving solidarity, democracy, and emancipatory politics and highlighted blind spots and silences of a political model formed in the 1930s and 1940s. Today a certain idea of the working class is even claimed by the Right. The problem for the Left in both periods, like any other political movement, is to hold together a coalition of both old and new constituents.

To succeed, then as now, it needs to build a popular coalition for change that can lead different groups and class fractions, despite the challenges that come with it. This is a problem of politics because it is at the political level where such social contradictions are ultimately reconciled. In both periods, leaning too heavily on rigid ideas of class can lead to conservative political conclusions and missed opportunities.

The last question is how could your account of the Left of the past help inform strategies around the working-class struggles of today, from the prospects of new left parties to Zohran Mamdani’s mayoral campaign?

I think the lesson is that what the “Left” and “working class” mean can be subject to simultaneous moments of transformation that have to be negotiated and constantly managed. Ideally the agility to command these processes needs to be actively and preemptively built into the political relationships that surround them, holding them together.

This should involve recognizing that it is often those at the margins of the working class who can make significant contributions to the movement. Actively involving such marginal groups can come with both costs and opportunities. From my analysis, their key contribution is that they bring with them significant dynamism that doesn’t have to be destabilizing but can be developed and channeled, particularly when acting in concert with and supported by preexisting structures.